Death of Coco Lee Triggers Public Discussion on Depression in China

Legendary Chinese American singer Coco Lee’s death on Wednesday has sparked widespread discussions about depression and mental health among Chinese netizens.

Multiple hashtags focusing on the contrast between Lee’s public persona and private struggles have trended on microblogging platform Weibo, including “smiling depression” and “optimistic pessimist.”

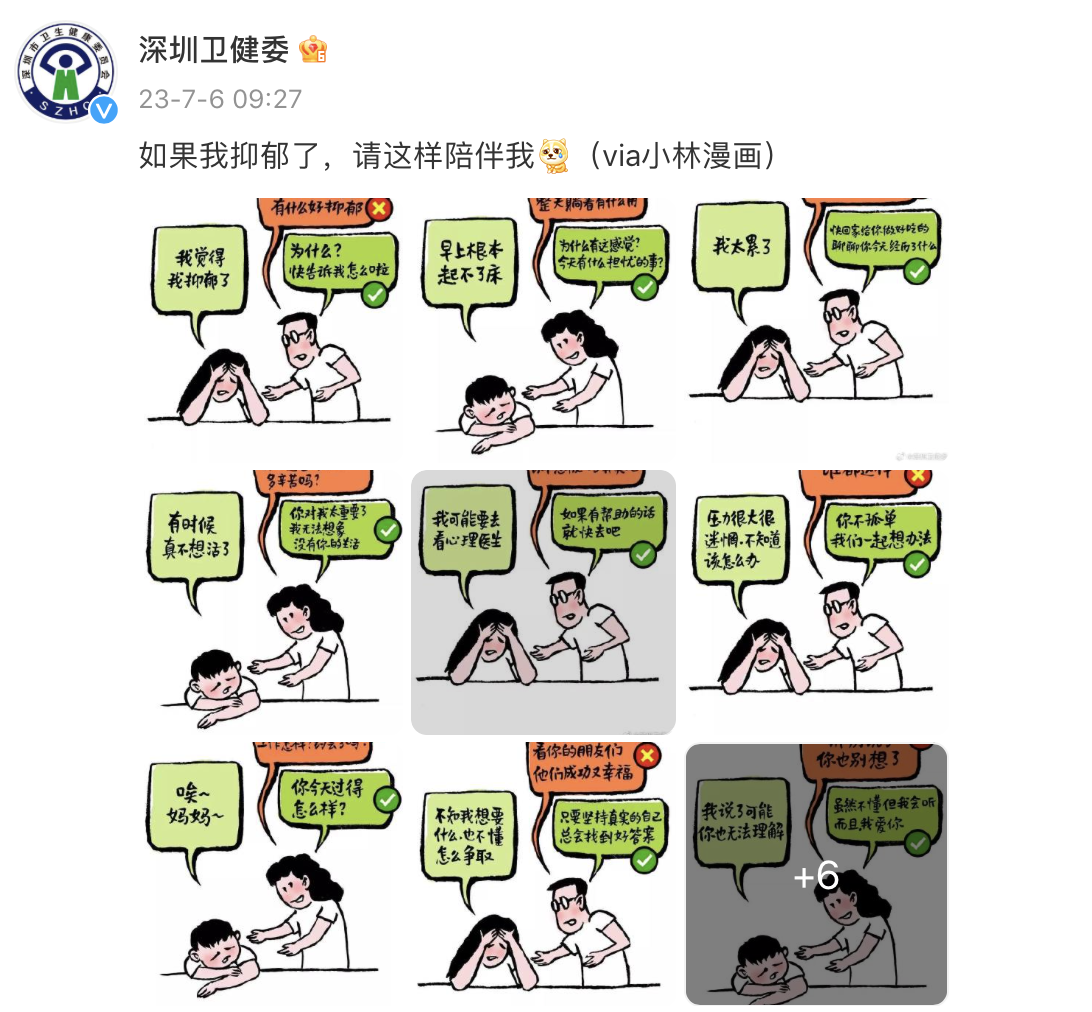

Official accounts of health authorities and state-owned media outlets have also published articles about recognizing signs of depression among friends and family, and how to have conversations about mental health.

“People should go for psychological evaluations in mental health institutions to confirm their levels of depression after they have identified signs of it,” advised a long article published by the National Health Commission on its WeChat account on Thursday.

“Depression is not like a cold that can be cured without treatment,” it said.

The death of the Hong Kong-born singer from suicide was a huge shock for Chinese fans, many of whom associate her with a sunny disposition and energetic performances.

Lee was widely recognized in China for voicing the protagonist in the Mandarin version of Disney’s “Mulan” and performing a song for the award-winning film “Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon.”

Hundreds of thousands of fans and peers from the music industry have expressed their grief online. “Sorry for enjoying her warmth, without thinking about the setting of the sun,” the official Weibo account of music competition show “Infinity and Beyond” posted, on which Lee was a guest last year.

Lee has been a frequent presence on hugely popular Chinese music reality shows in recent years, including “Infinity and Beyond,” “I Am a Singer,” and “The Voice of China.”

According to the World Health Organization, depression and anxiety are the two most prevalent mental health disorders in China, with around 54 million and 41 million affected, respectively. A recent study from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention showed that suicide rates increased during the COVID-19 pandemic, which may be related to greater levels of social isolation and financial hardships during this period.

A 2017 survey of 10,000 people found that half of the respondents first learned about depression from celebrities and other breaking news. The previous year, singer Qiao Renliang died by suicide due to severe depression, which also sparked discussions about depression at the time.

In recent years, China has made efforts to overcome the barriers preventing people from accessing mental health treatment, including a target for depression treatment rates to increase by 80% by 2030.

Peng Daihui, director of the mood disorders department at Shanghai Mental Health Center, tells Sixth Tone that patients suffering from “masked depression” and “smiling depression” — living with depression on the inside while appearing happy on the outside — are to be expected as emotions are complicated.

“Having different feelings is normal for human beings,” Peng says. “But when these feelings make you unable to function, affecting normal life and communication, then the function is missing.”

Although the public has found it difficult to associate Lee with depression, some, like Wei Liang, a student who has suffered from depression for seven years, was less surprised to see the news.

“I understand that it can happen to anybody,” Wei tells Sixth Tone, using a pseudonym to protect his privacy. He also considers himself an “optimistic depressed” person, who keeps his struggles to himself.

“Most people still can’t understand why optimistic people can be depressed,” Wei says. “But these judgments can make the patient feel worse.”

With mental health still a taboo issue in China, Peng says that a better understanding of depression among the public will help sufferers of depression open up about their struggles.

“Those who have more knowledge about depression would be more comfortable to communicate with,” Wei says.

In China, the Beijing Suicide Research and Prevention Center can be reached for free at 800-810-1117 or 010-82951332. In the United States, the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline can be reached for free at 1-800-273-8255. A full list of prevention services by country can be found here.

Shanghai’s 24-hour mental health hotline can be reached at 962525. Phone numbers for the city’s other hotlines can be found here and here.

Additional reporting: Xu Cen; editor: Vincent Chow.

(Header image: Coco Lee performs during a show in Nanjing, Jiangsu province, Dec. 1, 2012. VCG)