The Villages Caught Up in China’s Massive Panda Conservation Drive

SICHUAN, Southwest China — When China announced plans to create a huge new national park to protect the habitats of wild pandas a few years ago, it triggered an outpouring of support from people across the country.

In Wannian Village, however, the news was greeted with some trepidation.

The village, perched high in the mountains of western Sichuan province, was located just inside the boundary of the proposed park. That meant life in the area was about to undergo dramatic changes.

The new policy would introduce tight restrictions on human activity within the park, including outright bans on coal mining and hydropower. Though these industries were already in decline in Wannian, they were still pillars of the local economy. Local officials knew that many villagers would lose their main source of income.

“It was a huge challenge to push forward the changes,” Wang Meisu, an official at the local township government, tells Sixth Tone. “There were still dozens of those facilities.”

Wannian is one of thousands of villages that have had to undergo a radical transformation over the past few years, as China pushes forward with a massive drive to protect its wild panda population.

The Giant Panda National Park, which officially came into being in 2021, is a hugely ambitious project. Stretching across 27,000 square kilometers of countryside in Sichuan, Shaanxi, and Gansu provinces, it connects up dozens of existing conservation areas and benefits from lavish funding.

Supporters of the park say it will provide a major boost to efforts to protect China’s pandas. The species has rebounded in recent years — with the wild population estimated to have reached around 1,800 — and Chinese authorities are determined to keep this figure growing.

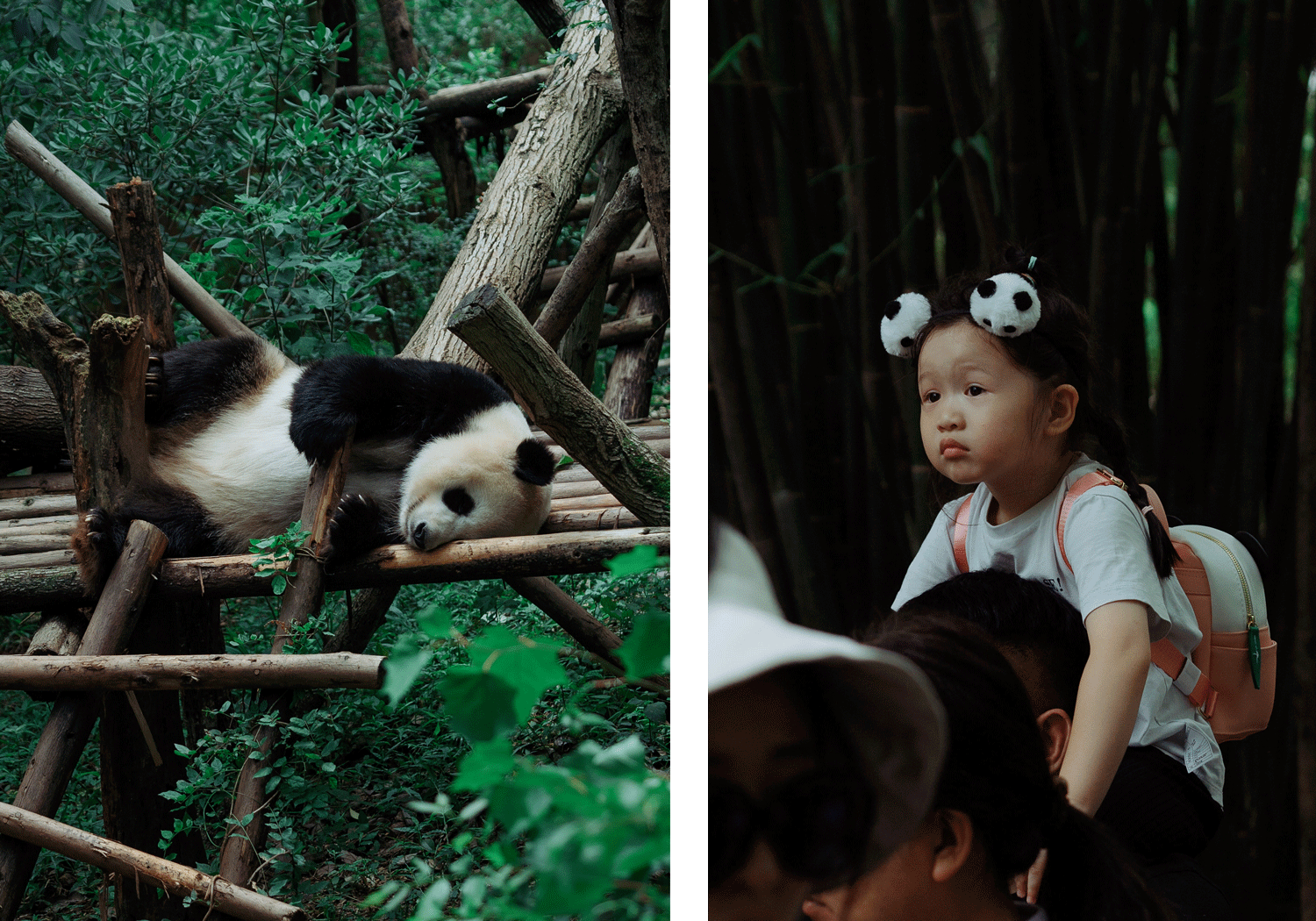

Next to Wannian is a training center where Chinese wildlife experts are trying to teach young pandas who grew up in captivity to survive in the wild. The hope is that the park will provide enough room to allow a higher number of bears to survive and thrive in their natural habitats.

But there is an issue with the plan: The land is already occupied. Tens of thousands of people were already living in the area at the time the park was announced. And many of them were making a living through activities that were outlawed under the new policy.

To solve this problem, the villages have had to act boldly. Many, including Wannian, have tried to transform themselves from industrial hubs into tourist resorts, wagering that the national park will bring a surge of visitors to the area.

Wannian has rebranded itself as a “panda village,” and covered its roads and buildings with panda-themed decorations. Restaurants, hostels, and souvenir stores selling panda toys have opened along the main street.

For local people, it often hasn’t been an easy transition: Many are elderly, have little formal education, and have rarely traveled outside the village. Some only speak their local dialect and barely understand Mandarin Chinese.

But as China’s tourism market bounces back after the pandemic, there is optimism in the village that their bet on tourism is starting to pay off.

‘Humans retreat, pandas advance’

Wannian is part of a cluster of villages sitting at the southern tip of the Giant Panda National Park. Even before the park was announced, it was clear that the region was in trouble and needed to change.

For decades, mining, logging, and hydropower were the main industries in Wannian. At its peak in the 2000s, there were around 50 coal mines in this tiny village of just over 1,000 people.

The projects were profitable and created a lot of jobs. “We were making good money,” recalls Tao Yonghu, Wannian’s deputy party secretary, who owned a mine employing 100 people during that period.

But the mines were ruinous to the local environment, creating nasty pollution that contaminated the water supply.

“Villagers here used water from the river for their daily lives,” says Tao. “But when it rained, the rain flushed down coal into the river … It used to be a black river.”

By the mid-2010s, tightening environmental regulations had already forced a number of local mines to close. But the announcement of the park still generated significant unease in Wannian. Wang, the township official, still recalls how difficult it was to implement the new rules.

“Each county-level official was responsible for shutting down one enterprise,” she recalls. “They were responsible for persuading the business owners.”

There only appeared to be one way out: turning the village into a tourist hotspot. Wannian has several natural advantages: It’s only 200 kilometers from Chengdu, the capital of Sichuan province. Yet, it’s also surrounded by bamboo-covered forest that is beautiful now that the heavy industry has been phased out.

The village also sits right on the southern tip of the park, making it a great jumping-off point for visitors. Plus, the nearby panda training center is famous all over China. Wild pandas are rarely seen near Wannian these days, but many locals have stories of run-ins with bears in the past.

Local officials quickly set about rebranding Wannian as a “panda village.” The place was given a complete makeover. Cute panda sculptures were placed along the winding path leading from the highway. Panda murals covered the walls of local buildings. Hostels named after famous pandas were set up.

Things didn’t go smoothly at first. Local resident Zhu Yan became the first villager to open a store in 2017. (Previously, locals simply grew their own food or bought what they needed at local wet markets.) She set up her business in a prime spot at the entrance to Wannian, next to the main road. But hardly anyone came.

“There weren’t many visitors,” she says. “The business was stagnant.”

There were other problems, too. Chen Sha — a resident of Fazhan Village, just a few kilometers down the road from Wannian — was also one of the first people to respond to local officials’ calls to explore the tourism industry. She opened a small hostel catering to the trickle of visitors then passing through the village.

But Chen had no idea what she was doing. Like many locals, she had spent time living in a nearby city — where she ran a clothing store — but she had rarely traveled beyond her small corner of Sichuan. She didn’t really know what middle-class Chinese visitors would expect from a hostel.

“It’s hard to believe, but some of the rooms didn’t have bathrooms at the beginning,” laughs Chen. “It was the visitors who assured me it’s a must! We had very little understanding of the tourism business.”

The panda economy

Now, however, the local tourism industry is starting to take off. The main road in Wannian now has 18 businesses, including restaurants and souvenir shops. There are over a dozen hostels, and most of them are close to full when Sixth Tone visits in July.

Near Zhu’s store, several elderly visitors sit painting watercolors of the mountain scenery. Zhu says that business has picked up the past couple of years, thanks largely to an influx of seniors from elsewhere in Sichuan.

“More old couples have been coming to the village,” she says. “My revenues have been growing steadily.”

Several things have helped put Wannian on the map. The opening of the national park in 2021 generated enormous public interest in China, and panda-related tourism in general has undergone an extraordinary boom since the country’s “zero-COVID” restrictions ended in late 2022.

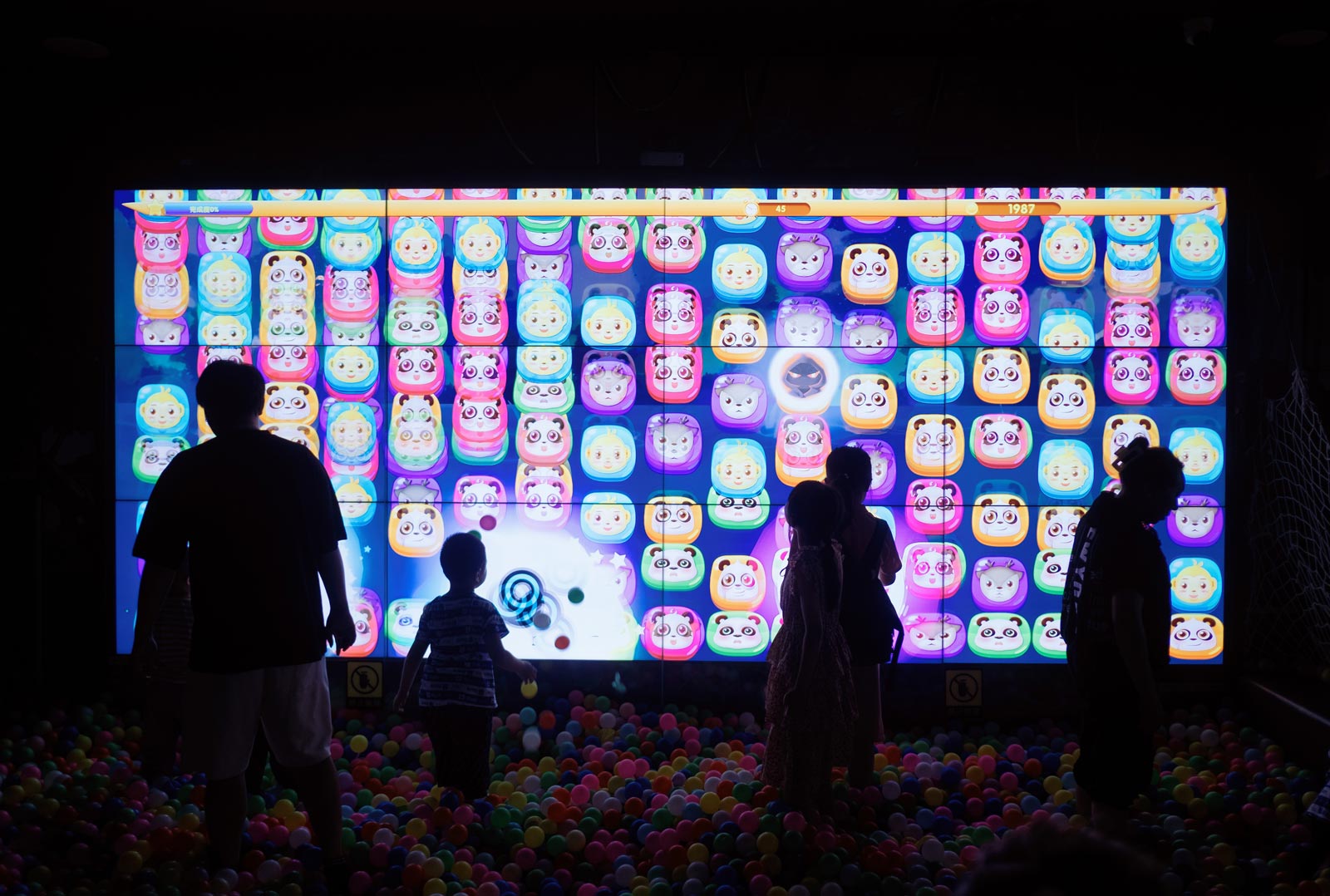

Chengdu — home to three panda breeding centers — has always been popular with tourists. But things have gone up a gear this year. During major holidays, tickets to the main panda research center have been selling out within seconds online.

Inside the facility, visitors often have to line up for several hours to see the most “internet-famous” pandas. Souvenir stores are charging an eye-watering 1,800 yuan (around $250) for cuddly toys of these star bears — and even then they’re struggling to keep up with demand. “There’s a one-month waiting list for those toys now,” one vendor tells Sixth Tone.

All of this seems to be creating a spillover effect, as tourists who are unable to get into Chengdu’s top attractions seek out alternative panda-related destinations. Longcanggou, the township in which Wannian is located, is one of the beneficiaries.

Around 400,000 people now visit the town each year, which is a lot considering the place only has around 3,000 permanent residents, says Wang, the township official. In Wannian, the village committee estimates that local residents’ average income level will jump from 19,000 yuan to 22,000 yuan this year thanks to rising tourism revenues.

“This is just the average level,” says Yang Xiaolin, the village’s party secretary. “Forty percent of the residents are aged 60 and above. Young people who are actively working can definitely earn much more than the average.”

And locals are confident that the number of visitors will only keep growing. Wannian still has some glaring weaknesses as a tourist destination. Despite being nicknamed the “panda village,” there aren’t any live pandas for visitors to see. In fact, there’s currently very little to do in the village.

“The base preparing pandas for life in the wild isn’t open to the public,” says Tao.

The village is working hard to fix these problems. After months of lobbying, they have finally convinced the Sichuan provincial government to send them several pandas, which are supposed to arrive in late 2023.

There are also plans to open a “nature education base” that will teach visitors about pandas and their habitat, and to create hiking trails in the mountains. Once these projects are complete, Wannian will become a more enticing destination, Tao believes.

“I led the village out of poverty at the end of 2017,” says Tao. “Now we’re aiming for a better life for everyone.”

Changing lives

For many locals, life has undeniably improved since the national park was first proposed. Before opening her store, Zhu did a variety of jobs: working at a local hydropower station, at an electronics plant in Chengdu, and as a clothing vendor in other nearby cities.

The work paid enough for Zhu to get by, but it required long separations from her family. For several years, Zhu barely saw her two children except during national holidays.

“They were left behind in the village while I was working outside,” she says.

The store hasn’t made Zhu rich, but it has allowed her to live with her family full time again — which was all she wanted when she decided to move back to Wannian. And she’s far from poor: Last year, she invested 40,000 yuan to open a restaurant in the village.

“In the long run, there will definitely be more people coming,” she says. “The environment in the village has changed significantly. It’s such a clean place now.”

In neighboring Fazhan Village, people are even more bullish. Chen’s hostel has gone from strength to strength since she renovated the business in 2018: Her revenues have soared from 30,000 yuan to 500,000 yuan per year, and she has been able to hire seven of her relatives to run the place.

“They used to work labor-intensive jobs like growing tea or cutting down bamboo,” says Chen. “But now they have less physically demanding work, and their incomes are stable and increasing steadily.”

The success of the tourism industry has even convinced large numbers of former villagers to come back to Fazhan. When Chen was young, most of her peers left to find work in the city after finishing school, as they didn’t want the jobs on offer in the village.

“It’s risky to work in a coal mine and the hydropower station jobs are boring,” says Chen. “The income was meager. You couldn’t see a future.”

But now, around 80% of those people have returned to the village, according to Chen. Unlike in Wannian, Fazhan’s tourism market is booming: Chen’s main concern at the moment is that the village didn’t adequately prepare for the surge in visitors this year.

“Their plans can’t cope with the expanding scale of tourism,” she says. “When more visitors arrive, they produce more garbage and wastewater, and we’ve failed to provide enough entertainment.”

Yet, not everyone has been a winner from the park. Huang Jianyin, 59, has spent his life working in the mountains near Fazhan Village. During previous decades, he was a logger and farmer. Now, he is a forest guard — paid to patrol the mountains and alert the park authorities to any signs of illegal hunting activities, fires, or landslides.

The job pays Huang nearly 2,000 yuan a month, which is barely enough to support himself. He supplements his income by keeping bees and growing bamboo and traditional Chinese medicine herbs, which is permitted in the “non-core” areas of the park.

“People have to be aware that the panda park can’t provide us with a lot of jobs,” says Huang. “The local villagers can’t abandon growing cash crops.”

Huang also lost his home to the village’s tourism strategy. In 2016, he was among 100 villagers who agreed to be relocated to make way for a new tourist attraction. But seven years later, their new apartments have yet to be delivered.

“I’m generally content with my life today … Our living environment has been greatly improved with newly paved roads and new fitness facilities,” says Huang. “But it would be better if we had stable homes to live in.”

Huang is able to rent an apartment from a relative at a low rate, so the delay hasn’t caused him too much trouble. But elderly villagers — like Huang’s mother, who is in her 80s — have had a hard time finding temporary accommodation, Huang says. Landlords are reluctant to rent to seniors, as they believe it’s inauspicious if someone dies on their property.

“It’s a sad thing, but a few elderly villagers passed away before our new homes were ready for us,” says Huang.

Contributions: Zhang Han; editor: Dominic Morgan.

(Header image: A panda on patrol at the Chengdu Research Base of Giant Panda Breeding, Sichuan province, July 2023. Wu Huiyuan/Sixth Tone)