In China’s Dance Schools, a Dangerous Obsession With Weight Loss

SHENZHEN — When 12-year-old Ziqi won a place at a specialist art school in April, it was a proud moment for her family. The school has one of the most competitive dance programs in the country: Thousands of students apply each year, but only 30 are admitted. Training there would allow Ziqi to achieve her life’s ambition of becoming a professional dance teacher.

“We were very emotional when we found out the result,” Yao Yanlin, Ziqi’s mother, told Sixth Tone. “She’s talented and hardworking.”

But the family also felt some anxiety. Ziqi’s preparations for her entrance exam had concerned her parents: The girl had cut down on food while training intensively, insisting that she needed to have the perfect figure. Her weight rapidly dropped from 34 kilograms to just 25 kg. From the side, her daughter looked like a “sheet of paper,” Yao recalled.

And life at the school might be even more intense. Yao has heard stories of dance students competing with each other to lose weight, believing it will give them an edge. For this reason, she insisted that Ziqi only apply to art schools in Shenzhen, where her family could keep a close eye on her.

“This way, our daughter can fulfill her dreams and we won’t worry too much about her being far away,” Yao said.

Public concern is rising in China over a troubling culture of weight loss inside the country’s dance schools. As competition for places gets ever more fierce, students are going to ever greater lengths to become rake-thin — often developing anxiety, eating disorders, and other mental health issues as a result.

Though similar problems exist at dance academies all over the world, the situation inside Chinese schools is particularly worrying, industry insiders say. Teachers place an excessive focus on dancers’ physiques, with some urging girls to get “as thin as lightning.” Students often feel that their best chance of success lies not in improving their dance technique, but in shrinking their waistlines.

In China, the most common route to a professional dance career is via one of a few dozen specialist art schools. Children take entrance exams to gain admission to the schools at the age of 11 or 12. If they succeed, they spend the next six or seven years receiving professional dance training, before graduating with the equivalent of a high school diploma.

The entrance exams are famously intense. At the top schools, tens of thousands of applicants compete for just 20-30 spots, whittled down over three rounds of tests lasting several months. These tests focus not only on the children's ability as dancers, but also assess their physical appearance in extraordinary detail.

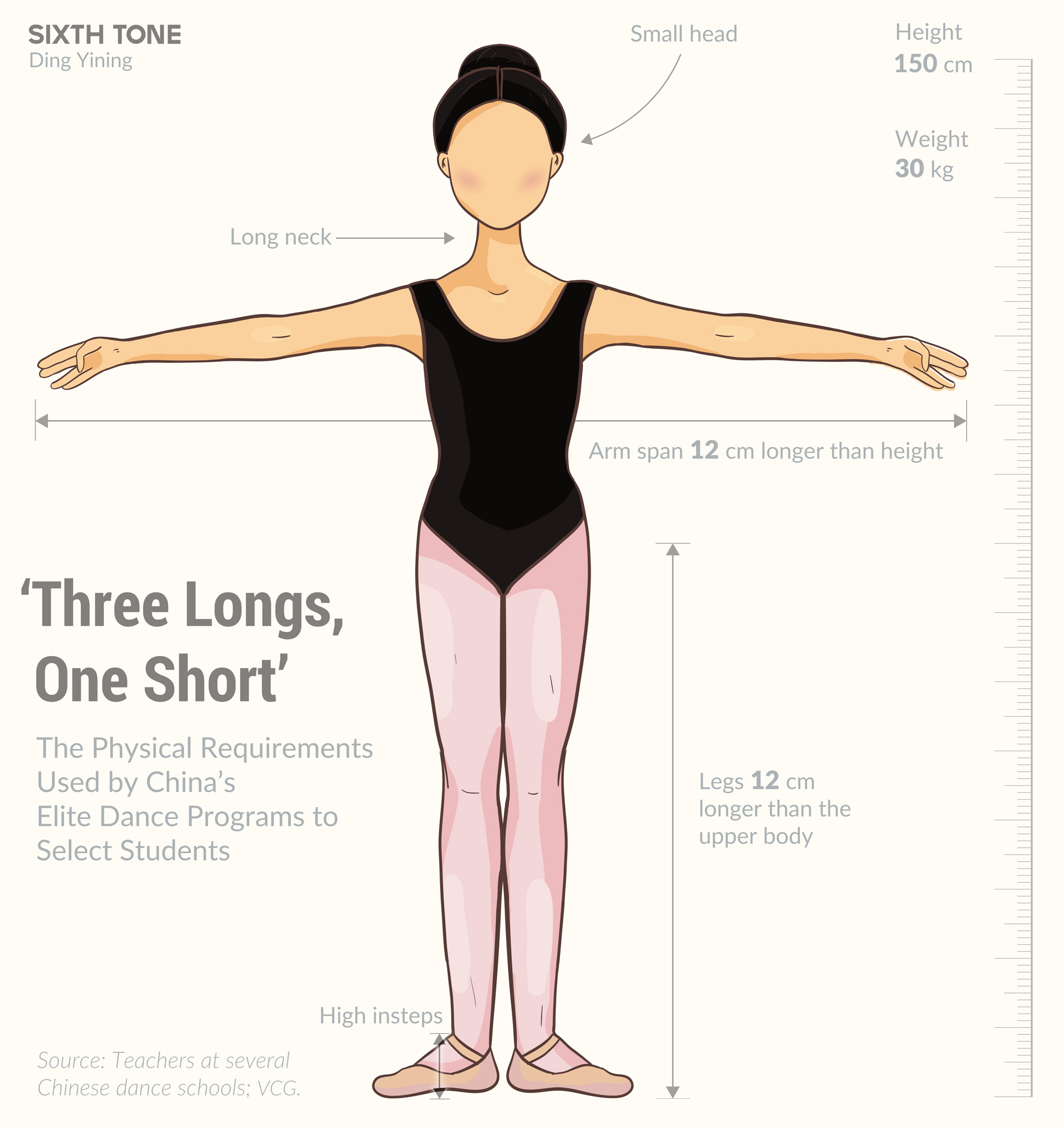

Even by the standards of the dancing world, Chinese instructors place an extreme emphasis on physical conditioning, industry insiders say. In most of the top schools, examiners will only consider students that comply with a body shape known as the “three longs, one small, one high, two 12s” — namely, long arms, long legs, long neck, a small head, high insteps, lower limbs that are at least 12 centimeters longer than their torso, and an arm span at least 12 centimeters longer than their height.

And the demands keep rising. China’s art schools have soared in popularity in recent years, making the exams even more competitive. A decade ago, Chinese parents were often skeptical about allowing their children to prioritize dancing over their academic studies. But that is far less true today.

As China’s middle class has grown, more consumers are paying to take dance lessons, meaning dance teachers can make a comfortable living. Plus, it’s easier these days for dancers to win fame and fortune thanks to social media.

“In the hope they’ll become TV stars one day, parents often make their children learn to dance or take art school exams,” said Xie Tianli, founder of Feeling Dance, a dance studio in Shenzhen that specializes in preparing students to take the art school entrance exams. “Last year, the number of applicants almost doubled compared with the previous year.”

Most children applying to art schools now need to have legs not 12 cm, but 17-19 cm longer than their torsos, said Xue Ping, one of the teachers at Feeling Dance. They’re also dieting harder than ever. Some children only eat liquid food before the exams to appear “very thin.” This became even more common during the pandemic, as the exams took place online and students worried they appeared heavier on camera.

“If they are shorter, they must be super thin or else they appear even shorter,” said Xue. “Some children may have psychological problems during the entrance exam year, because they lose weight excessively and their bodies reach their limit.”

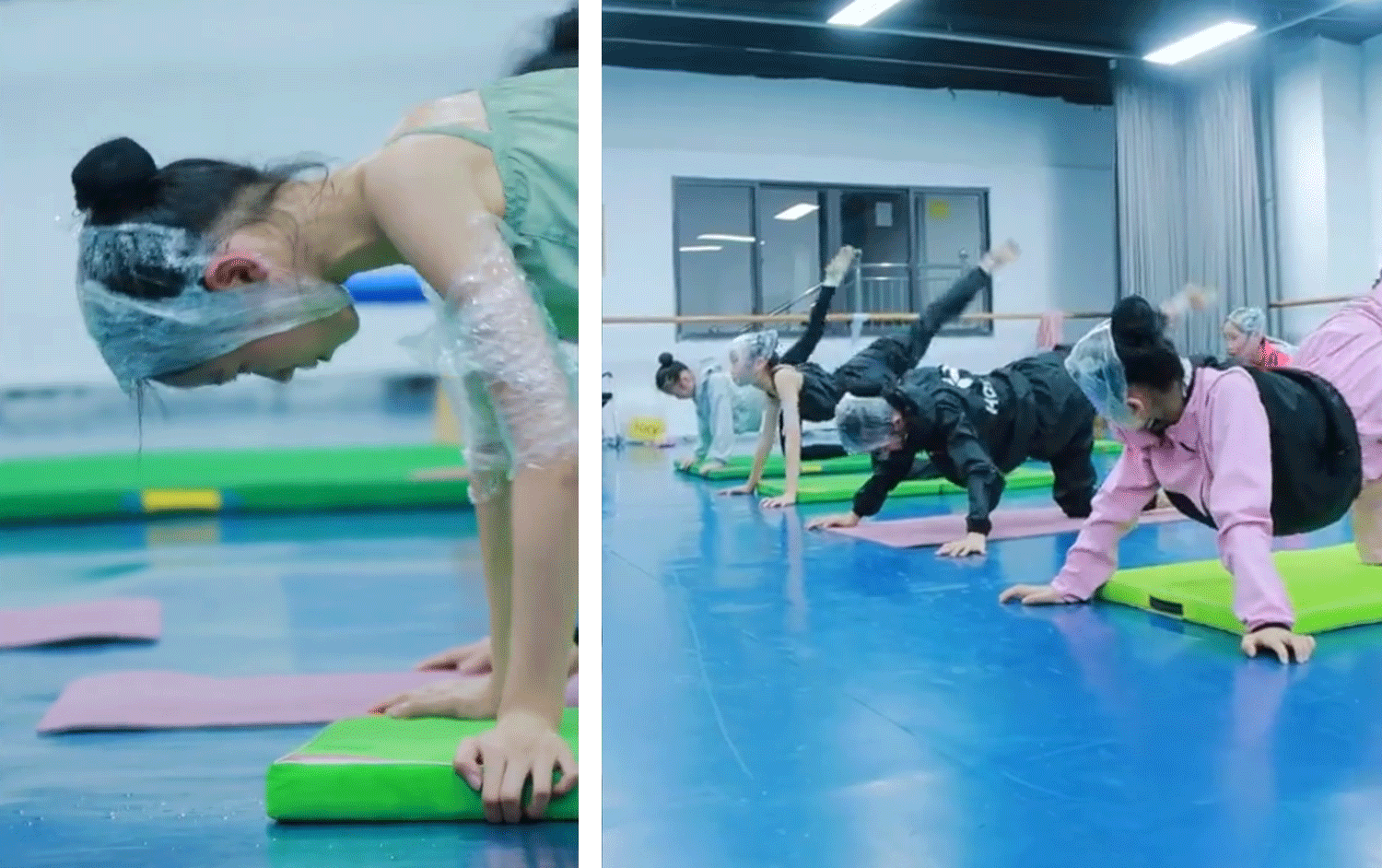

In some cases, dance schools are going to extreme lengths to make their students get super thin. In one viral video posted on Xiaohongshu, an Instagram-like social platform, a group of young girls train with their heads covered in several layers of plastic wrap. In others, students work out while their teachers urge them to get “as thin as lightning.”

These videos, which attracted tens of millions of views on Xiaohongshu, provoked a strong reaction from users, with many commenters criticizing the practices as “horrible” and expressing concern about the girls’ well-being. Others, however, pointed out that the nature of art school exams encouraged such training methods.

“If you are not thin enough, you’ll be eliminated in the first round,” one user wrote.

For Xue, the selection models used by Chinese art schools are “abnormal and too strict.” Luciana Bracco, a dance teacher from Mexico who has worked in Shenzhen since 2020, agrees.

“In China, it seems only a certain kind of body can dance, while others cannot,” said Bracco. “Some girls don’t meet the body requirements, but have everything else they need to be amazing dancers.”

Bracco has first-hand experience of the harm that such rigid attitudes can cause. When she was 16, her dance teachers forced her to go on a diet, saying she was “overweight.” She suffered from an eating disorder for years afterward as a result.

But in the rest of the world, it’s far less common to treat dance students this way nowadays, Bracco says. In the mid-2010s, a number of high-profile dancers began speaking up about their experience battling eating disorders, which sparked a culture change in the industry. China is at least five years behind the trend, according to Bracco.

Several students at Chinese art schools told Sixth Tone they had also suffered from eating disorders. Some resorted to extreme methods to lose weight, such as eating tissues or drinking body wash to make themselves vomit after eating. Several stopped having their periods after becoming malnourished. Others binge ate, or suffered from anxiety and depression.

These problems usually started when the children reached secondary school age. Often, the trigger was their first experience of receiving intensive dance training after entering art school. In other cases, it was hitting puberty, which caused them to become anxious and gain weight. By the time most students graduated, however, they had usually managed to gain control over their eating habits.

For some students, the treatment they received at Chinese art schools haunted them for years afterward. Ye Xiaolong, 20, passed the dancing entrance exam in 2015, but he received little attention from his teachers because his neck and limbs were deemed too short. He’s now studying dance at a top university in the United States.

“I felt treated unfairly,” said Ye, who spoke using a pseudonym for privacy reasons. “If you were to judge American dance students by the physical standards used in China, then two-thirds of my classmates here would be physically unfit.”

Wen Rouyue, 21, had a similar experience. She was accepted to a top Chinese dance school at age 12, but her dream of dancing onstage never came to pass, as her teacher considered other students to have superior physiques.

“My teacher ignored me and even hit me once, which caused me serious psychological distress,” says Wen, who also spoke under a pseudonym for privacy reasons.

The dance teachers who spoke with Sixth Tone had differing opinions on how China’s art schools should change. For Bracco, there should be much less focus on children’s physiques, and more effort made to cultivate their technique and passion for dancing. While many argue that it’s impossible for heavier dancers to train at an elite level without getting injured, she disagrees.

“Studies now show that it is not the dancer who is overweight, but the way we develop muscle in the wrong way,” she said. “The problem is not the dancer, it’s the teachers who work with those dancers.”

Xue, however, insists that it’s “right” to choose children in good shape to prevent injuries, though she agrees that schools currently go too far in prioritizing students with a certain body type. She says that students who don’t have the right physique are more likely to injure themselves, as they have to train more often and intensely than other dancers to keep up.

“Teachers also don’t want to spend extra time training children with average physical abilities, so they want to choose the ones with excellent innate qualities,” Xue added.

Yet, this selection method isn’t helping China compete on the international stage. At the 2023 Lausanne Dance Competition, the world’s most prestigious ballet contest, none of the Chinese ballerinas made it to the finals, with many observers blaming their technical and artistic shortcomings.

Xie argues that the failure was mainly a result of China’s three-year battle to suppress COVID-19, which forced Chinese dancers to train at home for long periods. But Bracco suggests that it’s a reflection of a deeper issue with China’s dance industry.

“Artistic expression is super important, and it’s something that most Chinese dancers don’t have,” Bracco said.

Xie admits that there is an element of truth to this. When she attends art school entrance exams, only half of the young applicants appear to genuinely enjoy dancing, she said. In many cases, the choice for them to learn dancing was made by their mothers, who often dreamed of becoming dancers as children.

Li Qian is one of those parents. As a child, she was passionate about art and dance, but she never had the opportunity to receive proper training. Now, she hopes her 12-year-old daughter Lingxi can have the life she was denied.

Li signed Lingxi up for dance lessons at a young age. From the third grade, it became clear that Lingxi had the right physique to become an elite-level dancer, and her teachers said she had a chance of making it to art school and becoming a professional. Li decided to sign her daughter up for the exams.

During the summer vacation, Lingxi’s preparations for the tests have stepped up. She has spent a whole month training every day from 7 a.m. to 9 p.m. When the new school semester begins in September, she’ll switch to training on weekends for a while. But in the run-up to the first exam in December, she’ll stop attending classes completely to restart intensive training.

This kind of training schedule is becoming ever more common as competition for art school places heats up, according to Xue. “Involution has become a much more serious issue,” she said. “Children must work harder now than ever before to gain admission.”

Like other parents of art school applicants, Li spends a lot of time worrying about her daughter’s appearance. Currently, Lingxi is just over 1.5 meters tall and weighs 35 kg. “Too fat,” Li said. “She needs to lose at least 5 kilograms.” To motivate her daughter, Li has joined her on a diet. “So far, the results have been positive.”

Though Li agrees that dancers need to stay in shape, she complains that the selection criteria used by art schools in China are too strict. Lingxi’s legs “only” measure 15 cm longer than her torso, she says, but she expects that this will rise to 17-18 cm by the time she takes her first exam.

And despite her desire to see Lingxi enter art school, Li admits that the prospect also fills her with anxiety. Like Yao, she worries that her daughter will feel pressure to compete with her classmates to lose weight, and that this will affect her mental health. She is also making plans to ensure the girl won’t be too isolated from her family after she starts school.

“Art schools, especially those with a lot of girls, are prone to competition,” Li said. “If she is lucky enough to be admitted to a first-class school in Shanghai or Beijing, her grandparents will move there to take care of her.”

Editor: Dominic Morgan.

(Header image: art-4-art/VCG)