Ex-Soldier Sleeps in Cave for 22 Years to Protect Song Treasures

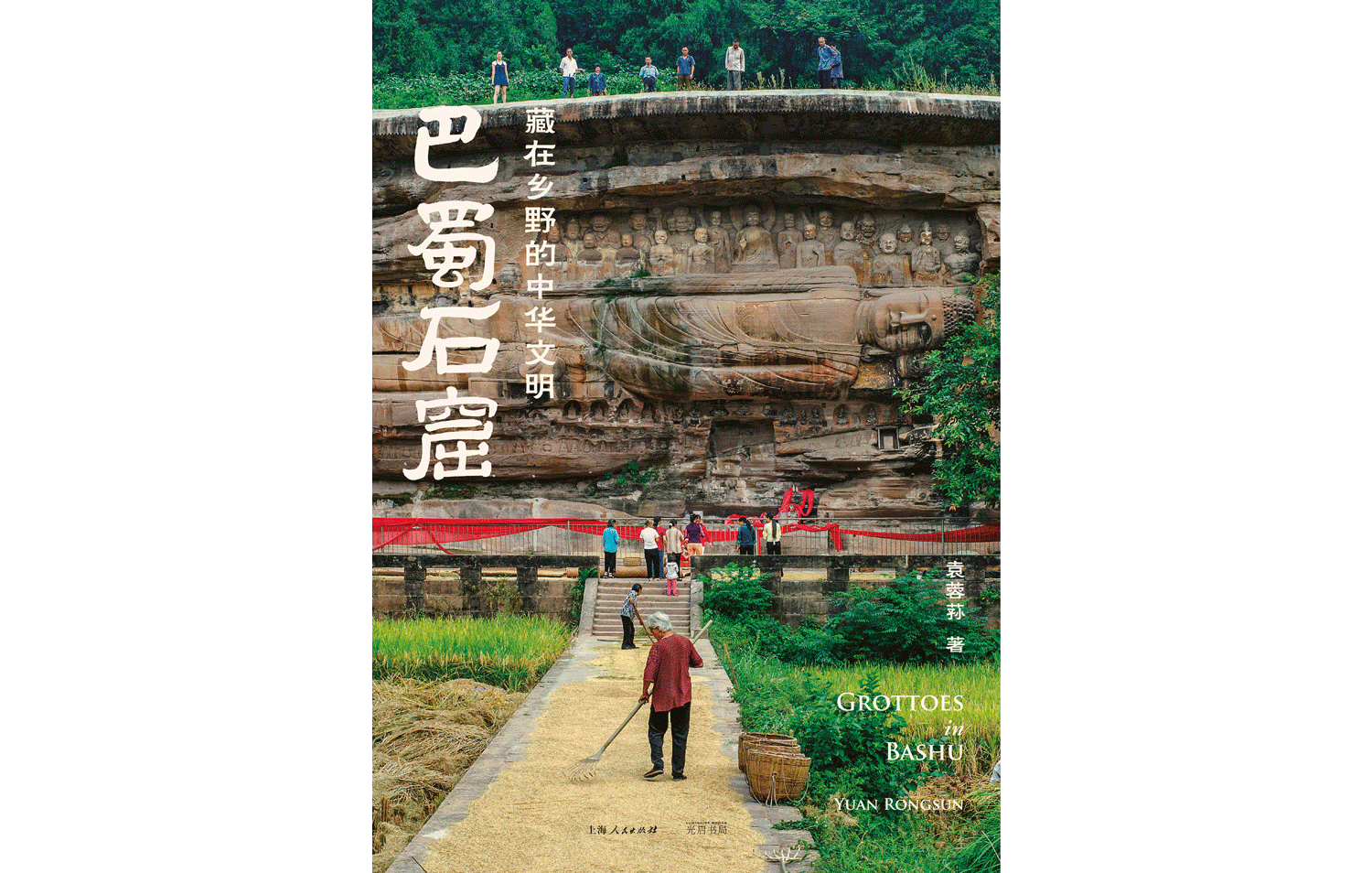

Editor’s note: “Grottoes in Ba Shu — Chinese Civilization Hidden in the Countryside” is a photobook published by Luminaire Books, an imprint of Shanghai People’s Publishing House, in October 2022. The book features 37 relics and contains 612 pictures of grottoes taken by the author over a period of 16 years.

Hailing from the southwestern Sichuan province, the author, Yuan Rongsun, is a researcher and contracted photographer of Chinese National Geography. For more than a decade, Yuan has been traveling the country, documenting all the grottoes that he can find. He has devoted himself to the study and dissemination of the history, culture, and art of grotto statues, and has held a series of photography exhibitions.

An important value of this book is that it stresses the need to protect cultural relics. The author casts his eyes on the custodians of the grotto relics, most of whom are local farmers who tend to these national treasures in their daily lives, often for little pay or even voluntarily. In the excerpt below, Yuan tells a story of a former soldier who has slept in a cave for more than 20 years.

The Huayan Cave Grottoes, which include Huayan Cave and the smaller Great Prajna Cave, are located in the southwestern province of Sichuan, six kilometers from Shiyang Town in Anyue County, and a little over 30 kilometers from Chongqing’s Dazu Rock Carvings. Night watchman Tang Pingchang has been guarding the grottoes for the past 22 years, protecting the site’s ancient cultural relics from thieves and vandals.

Tang was born and raised in one of the tile-roofed houses nearby. In 1949, the old temple beside Huayan Cave included more than 300 mu (50 acres) of land and was home to an elderly monk. When the property was divided during China’s land reforms, a portion of it went to Tang’s father, who built the house Tang still lives in today.

For generations, residents of Shiyang, including Tang’s family, liked to visit Huayan Cave because it was warm in winter and cool in summer. In their spare time, they would bring their children and elderly relatives, with the cave serving almost as a cultural and entertainment center for the community, one filled with golden Buddha and bodhisattva statues. Some people came to chat with neighbors, enjoy the cool air, and scoop water from the refreshing mountain spring that flowed into the cave. Others would bring handfuls of prayer candles to pay their respects to the holy statues and to wish for good fortune.

When Tang and his two brothers were young, they played hide-and-seek among the cave’s tall bodhisattvas, deftly leaping over and ducking under the statues. Their parents often had to tell them to stop fooling around for fear they might damage the Buddha’s gold paint.

In 1969, Tang joined the army and was sent to Shanxi province to train as a combat engineer. After five years’ service, he joined the Communist Party of China. When he left the army, Tang decided to return home to work as a farmer, which is when the local government first asked him to become a custodian for the caves’ cultural relics. He declined, feeling he was young enough to do something else with his time.

Years later, in 1999, the Huayan Cave Grottoes’ elderly custodian Li Kui decided to retire, leaving only his colleague, Chen Gaowen, to guard the relics. However, the job was too big for Chen alone. As a former soldier, Tang was a choice candidate to replace Li, so the town government and the Anyue cultural heritage bureau began calling Tang once again to offer him the job. They had reason to worry — thieves had stolen the heads of several arhat statues from Great Prajna Cave two years earlier, and the case was never solved. Tang eventually agreed to serve as custodian, taking a salary of 450 yuan a month.

Carving out history

The Huayan Cave Grottoes contain 159 statues dating back to the Song dynasty (960-1279) and 24 inscriptions carved during various other periods. In the center of Huayan Cave is a large engraving of the character “om,” the first word of the six-character Buddhist mantra, while Great Prajna Cave carries a relatively stranger engraving: In a circle about 2 meters in diameter is the word “ren”, or people, next to an upside-down version of the same character.

Huayan Cave was excavated in the first year of Jianlong (960) during the Northern Song dynasty. It stands at 6.2 meters with a width of 10.1 meters and depth of 11.3 meters. Along one wall is a 5.2-meter-high statue of Vairocana Buddha sitting alongside Manjushri bodhisattva and Samantabhadra bodhisattva. The Buddha is wearing a tall crown in which the Willow Buddha is carved sitting on a lotus platform with plump cheeks and half-open eyes. The bodhisattvas alongside it also have crowns carved with small Buddhas. Each figure wears a cassock with a wreath on their chest, and they are seated on the boulevard, beneath which is a green lion and a white elephant. On the walls to the right and left are statues of ten bodhisattvas, each standing 4.1 meters tall.

Surrounding these are also many beautiful stone carvings, each demonstrating the exquisite quality of Song craftsmanship. The hollowed-out ornamental flower crown, the countable bead wreaths, and the flowing cape folds all set off the elegant and luxurious image of the bodhisattvas. Above the heads of the bodhisattvas are carvings of Sudhana stories.

Great Prajna Cave is 15 meters to the left of Huayan Cave. Excavated in the fourth year of Jiaxi (1240) in the Southern Song dynasty, the cave is 4.7 meters high, about 5 meters wide, and 5 meters deep. The cave is an equally precious grotto filled with vivid and intricately carved Confucian, Buddhist, and Taoist statues.

Heartbreaking loss

For Anyue’s grottoes, which are scattered across the county, theft is a major problem. Even the Huayan Cave Grottoes have not been spared, despite being in a remote mountain location with no public road access. In July 1997, the heads of 18 arhat statues from the Song dynasty were stolen from Great Prajna Cave — a heartbreaking loss. That night, according to Tang, a villager from nearby Shuanglong was supposed to guard the cave, but he had instead gone home to help his family slaughter a pig. The next morning, Tang’s older brother was going to dig soil when he spotted wooden blocks and ropes on the road. Feeling something was wrong, he hurried to the caves and discovered that Great Prajna Cave had been raided. The following night, cultural relics were also stolen from the nearby Pilu Cave and Mingshan Temple using similar methods, presumably by the same gang of thieves. At the time, cultural heritage sites had no monitoring facilities. With no leads for police to follow, the culprits were never captured.

It was not long after this incident that Tang decided to return to his childhood home to guard the grottoes and protect the ancient relics within. He set up a small bed in Great Prajna Cave’s viewing room, with a flashlight under his pillow and a pole at his side. His dog accompanied him every night, keeping watch at the foot of the stairs. Through scorching summers and freezing winters, Tang has spent almost every night in the cave for the past 22 years. Officials from the cultural relics bureau occasionally made surprise visits to make sure the night watchman was on duty, but Tang’s deep sense of responsibility quickly set them at ease.

Tang has a son and a daughter, both of whom work in other parts of the country. Although they often ask their aging parents to stay with them to enjoy some family time, it is difficult for both Tang and his wife to take time off. Years ago, Tang went to visit his son and grandson in Ruili, Yunnan province, which meant his wife needed to stay behind to guard the caves.

Shock and awe

I got to know Tang after coming across his small bed in that dimly lit cave.

It was at the start of 2007 and the dirt road to the Huayan Cave Grottoes could still take you only halfway up the mountain. From there, you had to park on the side of the road and climb the rest of the way up flagstone steps. I remember that near Huayan Cave the path passed through a large bamboo forest. As we walked, two wooden houses with tile rooftops and flying eaves emerged from the dense bamboo, hiding Huayan Cave and Great Prajna Cave from view. Later, I learned why these two houses standing against the rock face looked so ancient — it turned out they were built in the 28th year of the reign of Emperor Qianlong during the Qing dynasty (1636-1912). The stone doorway that arched over the path several flights of stairs up was built some 20 years later. At that time, the stone altar in front of the three holy statues in Huayan Cave would have been illuminated with oil lamps that were never allowed to go out. A stone incense burner sat in the middle of the altar, filled with prayer candles offered by the villagers. And on the ground beside it were neatly arranged prayer cushions wrapped in red cloth. I was awed by the Song dynasty statues.

Next, I turned to Great Prajna Cave and went to the viewing room where I discovered a small bed under the dim light of a lamp. It was only when I asked Tang, who was cleaning nearby, that I learned he slept there every night to keep watch over the grottoes. I was so shocked that I couldn’t speak. Moved, I decided to get to know him.

Huayan Cave is among the cliffs and peaks of Xianggai Mountain. There were originally six stone pillars, but in 1982 a falling boulder smashed the top of the cave and broke in half the large stone incense burner, which had stood more than 1 meter tall and was carved during the Ming dynasty (1368-1644). Some large stones also fell from the roof, exposing Huayan Cave to the sky. The Sichuan Cultural Relics Management Committee allocated funds for repairs, and Anyue’s cultural administration office gathered more than 30 stonemasons and laborers to make repairs. Using temporary gangplanks the workers drilled the cave’s outer walls, chiseled the stone into slabs, and then carried them — shouting and straining — down the slope to create a flagstone stairway from the foot of the mountain to the caves. They built new supports inside Huayan Cave and reconstructed the ceiling with reinforced concrete. To reduce the impact of humidity on the statues, they blocked the natural springs that flowed into the cave.

After three years of careful restoration, Huayan Cave had regained its temple-like splendor. However, it no longer had the protection of its original solid stone walls, and the newly built concrete walls were in direct contact with the soil above. Over time, surface water leaked through the concrete along the junction of the wall and the ceiling, gradually corroding the surfaces of the statues. Unfortunately, the heads and bodies of the statues now show traces of water damage.

Tang told me that he also participated in the roof reconstruction, straining shirtless under the heavy stones day after day. The construction was done completely through traditional folk methods. Although it was backbreaking work, the laborers did their best to rebuild the roof and prevent rain damage to cultural relics. They earned 1.2 yuan a day, more than enough for daily living expenses at the time.

Sense of security

In 2010, Yu Mingqiang, a 40-something native of a nearby village, became another custodian of the relics in Huayan Cave, serving as Tang’s helper. After Yu started working on the mountain, his wife, Wu Tingbi, became responsible for running their family farm. She also would occasionally hike up the mountain to look after her husband and cook him meals while he kept guard during the day. Huayan Cave has no running water, so to cook and wash vegetables Wu had to retrieve water from a spring in the woods, which was no easy task. For the past 13 years, almost every day at 5:30 p.m., Yu has closed the door to the grottoes and walked down the mountain to his home, leaving Tang alone to stand watch until morning. Today, the two custodians earn 1,200 yuan ($166) a month.

I’m so fascinated by the exquisite statues of Huayan Cave that I linger every time I visit. Since arriving for the first time more than 10 years ago to photograph the statues, I’ve returned more times than I can count. In recent years, to further protect the relics, a waist-high wooden railing has been installed to prevent visitors from touching the statues. Worshippers can pray only using the prayer cushions outside the railing, and they can no longer burn candles and incense inside the cave. Security cameras also have been installed, including on the mountain roads, in the parking lot, and in interior and exterior areas of the caves, connecting the site directly to the Anyue cultural relics bureau and the public security bureau.

Although Huayan Cave’s national treasures and cultural relics now enjoy the protection of cutting-edge science and technology, Tang still slept in Great Prajna Cave every night, seemingly unable to let his guard down. The road to the Huayan Cave scenic area has been extended up the mountain, and the site’s large parking lot is right beside Tang’s house.

Among Anyue’s many grottoes, those at Huayan Cave are among the few open to tourists. In the past few years, when ticket revenues were at their highest, the site was bringing in 50,000 to 60,000 yuan a year. This figure has fallen significantly since the site began waiving entry fees for visitors over 60 years old and for local residents on workdays. However, as authorities and people around the country become aware of the grottoes and their cultural value, more out-of-province tourists are making the trip to the caves.

After a renovation of the environment surrounding the Huayan Cave Grottoes, the cultural relics bureau recruited three more custodians for the site in early 2021 — one of them being Wu Tingbi. In addition, two young people have begun working for the bureau to handle ticket sales, earning a monthly salary of 1,800 yuan.

Tang retired in early 2021, finally bringing to an end his days of sleeping in a cave. The bureau has struggled to find someone to take over his vigil.

This article, translated by Carrie Davies, is an excerpt from the book “Grottoes in Ba Shu” by Yuan Rongsun, published by Luminaire Books in October 2022. It is republished here with permission.

Editors: Xue Ni and Craig McIntosh.

(Header image: Statues of Bodhisattvas at Huayan Cave, photo taken by Yuan Rongsun, January 2001. Courtesy of Luminaire Books)