Gain and Pain: The Problem of China’s Expanding Waistline

China celebrated its 16th National Healthy Lifestyle Day on Sept. 1, an annual initiative that promotes the importance of good nutrition and warns of the dangers of a poor diet. This year’s theme, “Three Reductions and Three Healthy Conditions,” encouraged citizens to cut down on how much oil, sugar, and salt they consume, and to look after their weight, teeth, and bones.

The campaign’s message was likely heard by millions of people; how many of them will heed it is unknown. Research suggests that, as living standards improve, more and more people are facing the obesity problem.

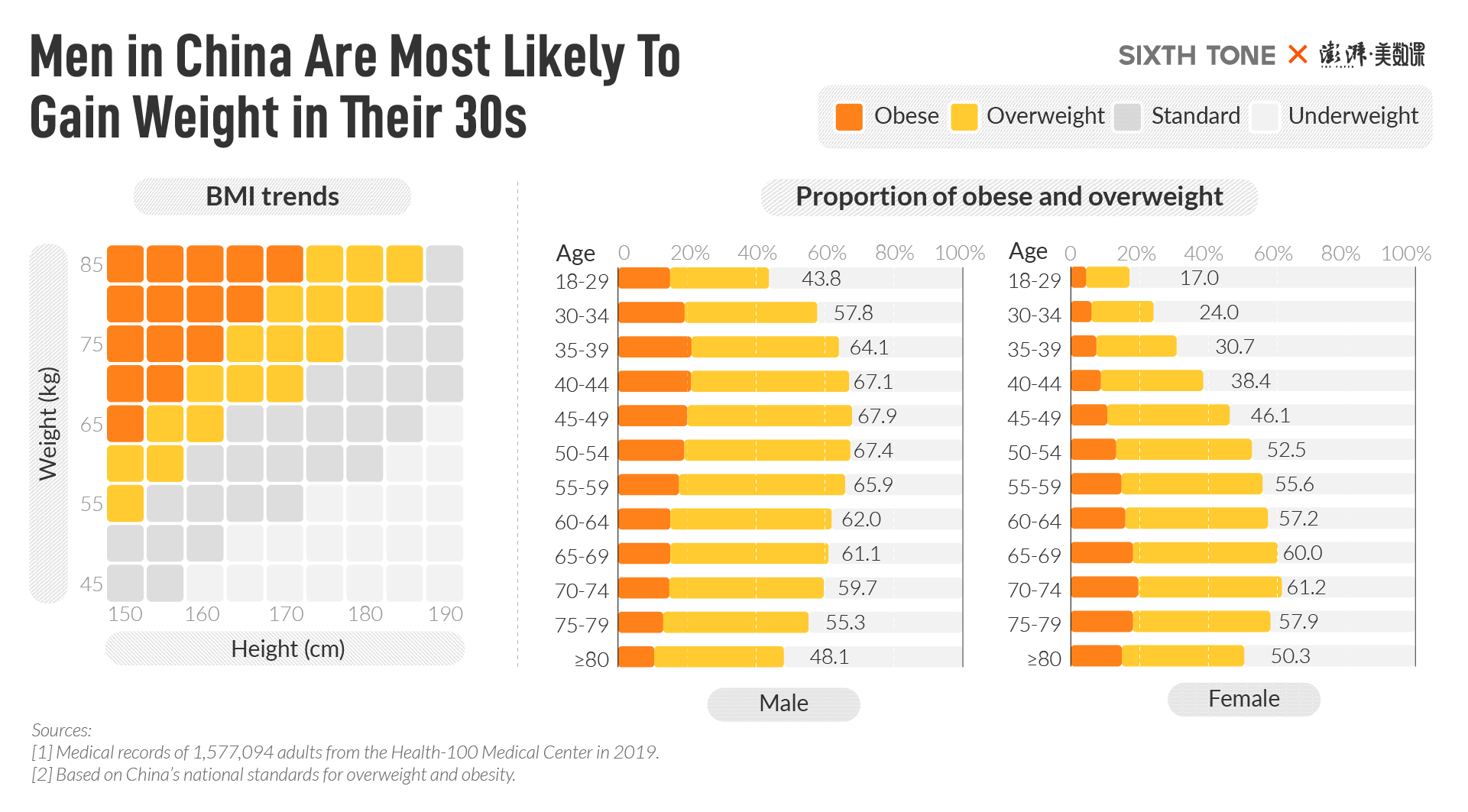

China’s national standards on physical wellbeing are based on the body mass index, which is calculated by dividing a person’s weight by the square of his or her height. Someone with a BMI of 24 is classified as “overweight.” Once it reaches 28, they are “obese.”

Using this criterion, a research paper published in the journal Diabetes, Obesity, and Metabolism recently estimated that 34.8% of the population is overweight and 14.1% is obese. The findings were based on a study of about 15.8 million adults across 243 cities by a research team from the First Medical Center of the Chinese PLA General Hospital, led by professor Mu Yiming. It is the largest investigation ever conducted into the prevalence and associated complications of obesity in China.

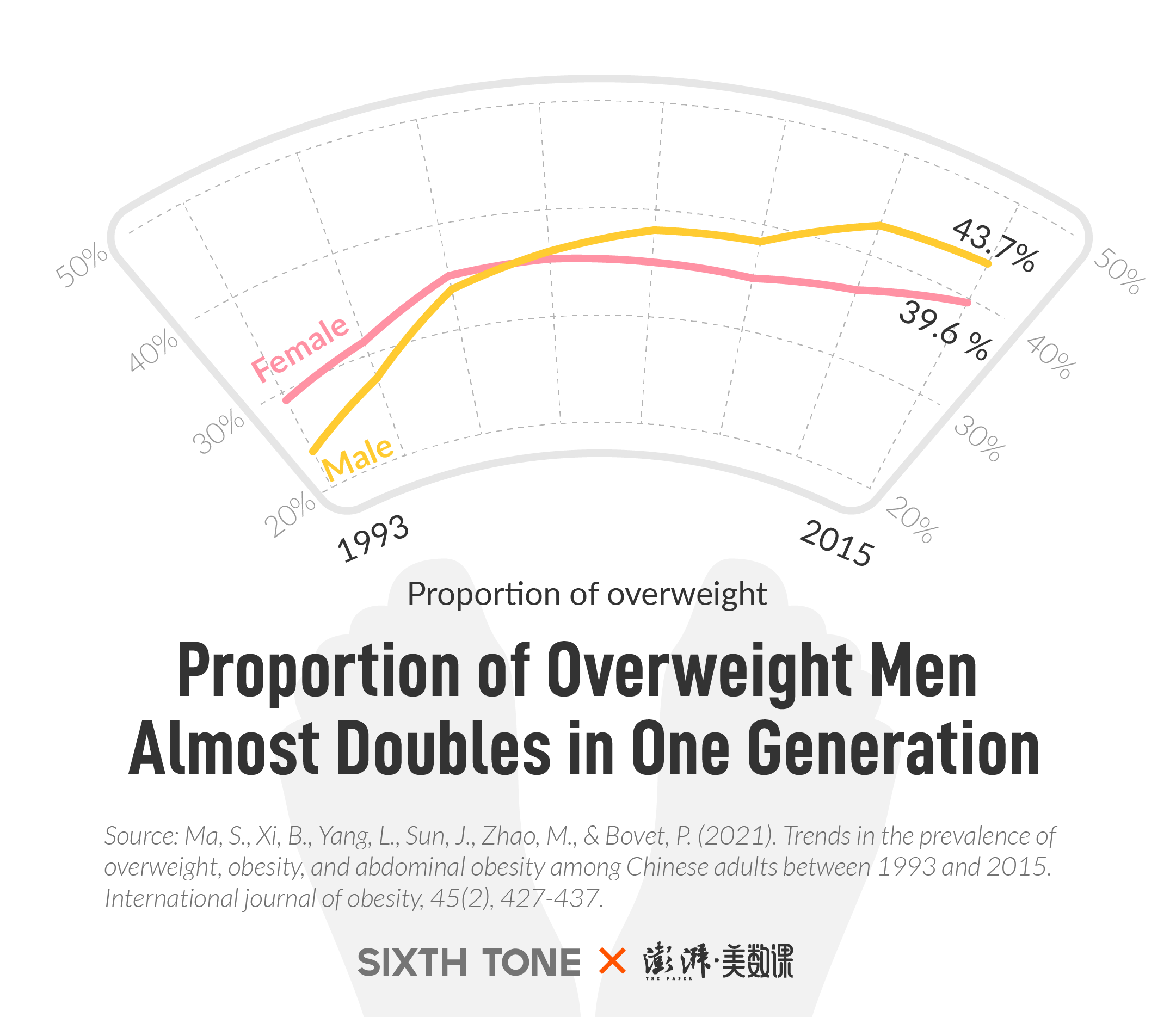

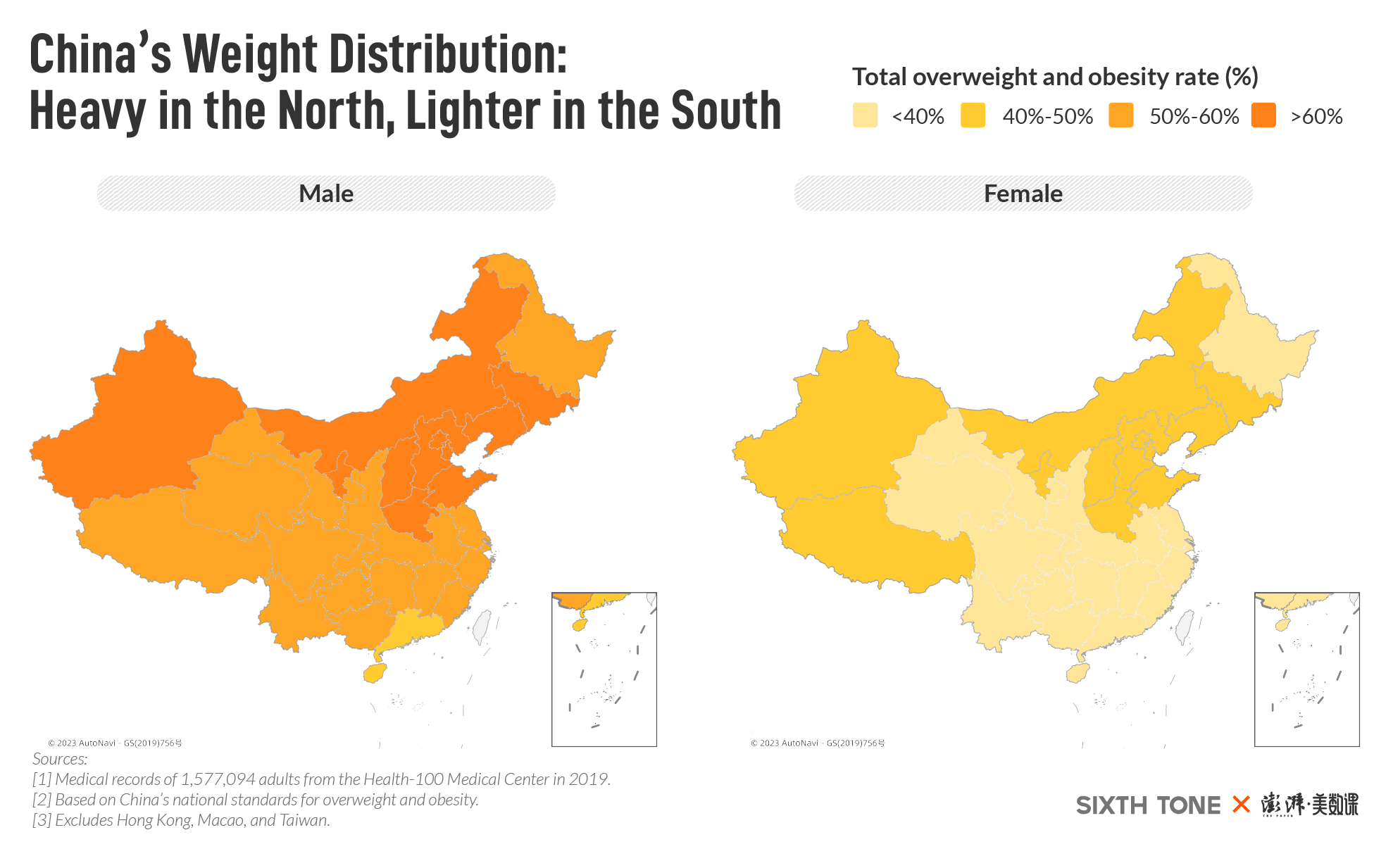

In addition to an increase in the number of overweight people, Mu’s team also noted another phenomenon: being overweight has become more common among men than women. According to the data, 27.7% of Chinese women are overweight and 9.4% are obese, compared with 41.1% and 18.2% respectively for men.

Earlier scientific studies showed that female participants faced a bigger struggle than their male counterparts in controlling their size, especially in the later stages of life. As a woman enters the menopause, her estrogen and progesterone levels will drop, causing a natural decrease in her metabolism, the process by which the body changes food and drink into energy, making it easier for her to gain weight.

However, in the 21st century, China has seen a rapid increase in the proportion of overweight men, far surpassing that of women.

China’s social and economic development may be a contributing factor in this new trend. A study published in The Lancet in 2013 found that in less-developed areas, women had a higher rate of obesity than men, while in developed areas, the reverse was true.

Eating more, exercising less

Chinese men and women also differ in what age they tend to start piling on the pounds. While overweight and obesity rates peak for women after the age of 70, for men the peak is in their 40s.

The research by Mu’s team also suggests that men pay less attention to their size once they pass 30 years old. An estimated 38.5% of Chinese males aged 30 to 34 are overweight, compared with 28.7% among 18 to 29-year-olds. The causes may include excessive stress, an irregular diet, alcohol abuse, and a lack of exercise. On the cultural side, Chinese society is also arguably more tolerant of men being “out of shape,” particularly in middle age, meaning there is less stigma attached to males gaining weight than for females.

However, the most fundamental factor is that people nowadays consume more food than previous generations. In the age of online takeout deliveries, people are tempted to eat too much and exercise even less.

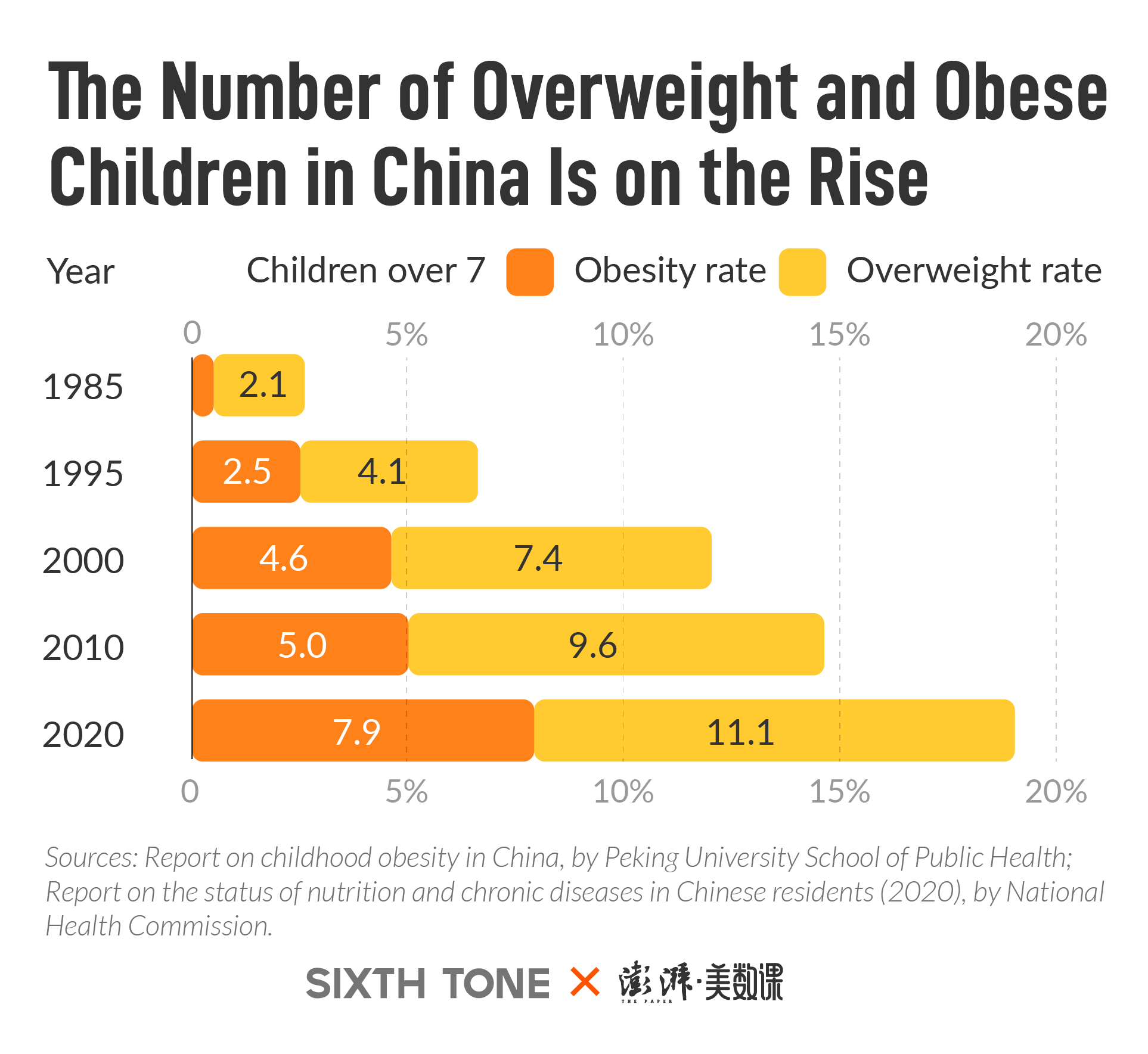

Obesity among young people is also a critical issue. A report by the National Health Commission in 2020 showed the proportion of overweight and obese children over 7 years old had risen to 19% from just 2.6% in 1985.

A common misnomer is that children naturally slim down as they grow older, but being overweight at a young age can have a serious and lifelong impact. A study by researchers in the United States that tracked the BMI of 11,591 obese children into adulthood discovered that 88% remained obese in later years.

North-south divide

In addition to differences in gender, obesity rates vary geographically, too. Mu’s team found that being overweight or obese is more prevalent in northern China than in the south, with the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region and the provinces of Shandong and Hebei having the most people who meet the criteria. People in the southern provinces of Guangdong, Hainan, and Jiangxi had the lowest prevalence.

The results align with the 2021 Urban Health Behavior Index released by Tsinghua University in Beijing, which scored the lifestyle habits of residents in 80 cities nationwide based on indicators including when they go to sleep and how much they exercise. The 10 cities with the lowest adult obesity rates were all in southern regions, such as Chengdu (2.65%) and Guangzhou (2.89%).

So, why are northerners more prone to being overweight? Wang Jingzhong, a researcher at the National Institute for Nutrition and Health, said that it is related to a variety of factors, from the regional climate to daily eating habits. For example, the warmer weather in the south can actually help speed up a person’s metabolism.

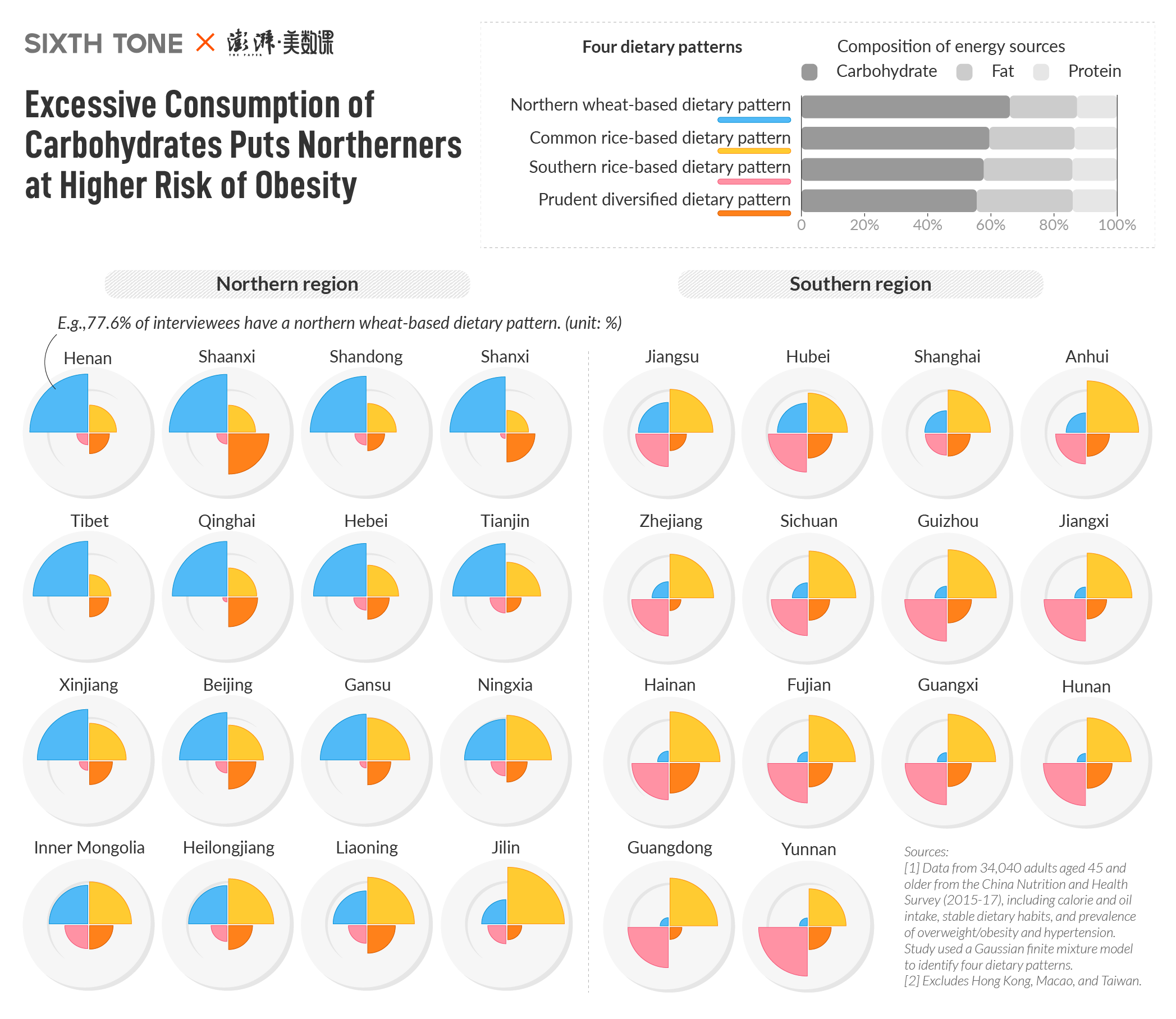

In 2022, a study published in the international journal Nutrients drew a similar conclusion after assessing the dietary habits of a sample Chinese population. It aimed to identify differences in dietary patterns by province, along with various health outcomes including obesity and hypertension.

The study categorized Chinese dietary patterns into four main types: common rice-based dietary pattern, prudent diversified dietary pattern, northern wheat-based dietary pattern, and southern rice-based dietary pattern. The main difference is the consumption levels of the three major nutrients: carbohydrates, fats, and proteins.

The northern dietary pattern gets over 60% of its energy from carbohydrates, considerably more than the other three patterns, which is considered the main contributor to the higher risk of obesity in that region.

A slower metabolism coupled with the higher consumption of carbohydrates make it much harder for people in the north to keep the weight off.

The Nutrients study also pointed out that dietary habits varied among groups from different socio-economic status. Those who chose healthier diets were concentrated in more developed areas, and were more likely to be well-educated and have a high income, it said. Similarly, the PLA General Hospital research found relatively high overweight and obesity rates in regions with lower GDP.

Of course, one major flaw in all this could be the use of BMI to define what is overweight and obese. The body mass index can only roughly assess the overall body situation; it cannot accurately determine the distribution of fat. Someone with a relatively low BMI could still have abdominal obesity and an excessive concentration of visceral fat around the stomach and abdomen, which affect the internal organs and pose health risks.

Abdominal obesity is defined nationally as a waist circumference of 90 centimeters or greater in men, and 85 cm or greater in women. A 2019 study published in Annals of Internal Medicine found that, based on this criterion, the prevalence of abdominal obesity in China had reached 31.5% by 2014, up by more than 50% compared with 2004. Again, northern residents were found to have the “thickest waists.”

Warning signs

At the second China Obesity Conference in Beijing, held in early August, Zhang Zhongtao, vice president of the Beijing Friendship Hospital, said that, by 2030, it is expected that health expenditures related to being overweight or obese will account for 22% of total medical costs in China.

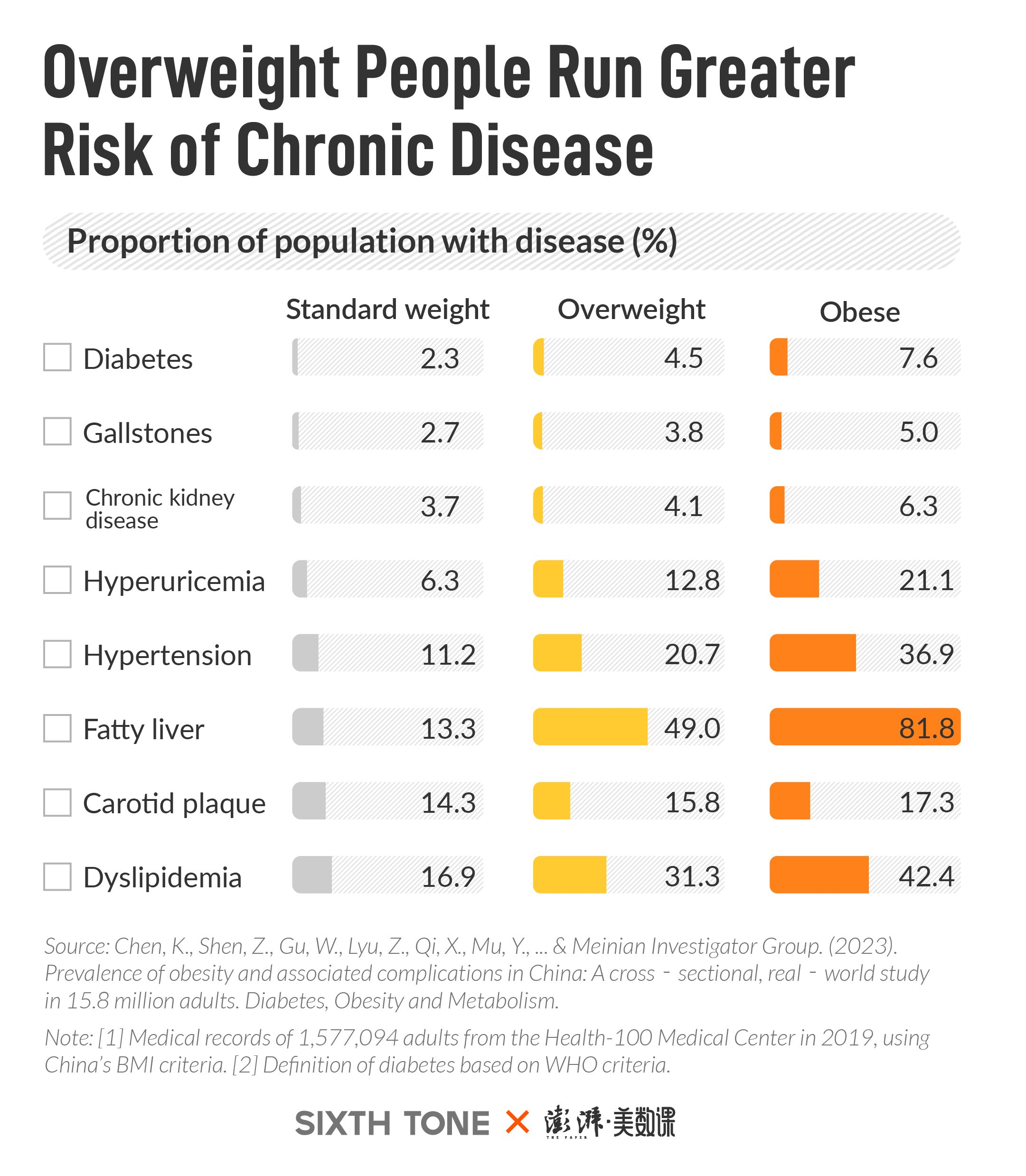

Health studies have shown that obesity is a major causative factor for diseases such as hypertension and diabetes. Compared with someone with a standard BMI, an overweight or obese person has a higher risk of complications, including chronic illnesses.

According to the study by Mu’s team, the proportion of overweight and obese people with at least one chronic disease was 70.7% and 89.1% respectively, higher than 41.7% of people with a standard BMI. Among the most common complications of obesity are a fatty liver (34.9%), prediabetes (27.6%), and dyslipidemia (24.9%). Today, an increasing number of overweight young people are developing these conditions, once regarded as geriatric diseases.

Nutritional transformation theory suggests that a country’s overall nutritional status goes through three phases alongside its socio-economic development, from hunger reduction, to a high prevalence of chronic disease, to behavioral changes. China has passed the first phase, and it is now experiencing the second.

Fortunately, many institutions, public groups, and individuals have noticed the dangers of obesity and are taking active measures. In August, the Shanghai Center for Disease Control began piloting an alert system for beverages as part of a countrywide initiative to combat health problems related to excessive sugar intake. Many supermarkets also now use red, orange, and green labels to inform consumers of the sugar content in different drinks.

More such efforts will be essential. Curing China’s obesity problem will require more than just self-discipline — it will need the whole of society to carry the weight of this challenge.

Reported by Wu Tiantian, Wei Yao, and Chen Liangxian.

A version of this article originally appeared in The Paper. It has been translated and edited for brevity and clarity, and is republished here with permission.

Translator: Wu Yichen; editors: Xue Ni, Luo Yahan, and Craig McIntosh.

(Header image: An Xin/VCG, reedited by Sixth Tone)