In Laos, a New Railway Signals a Future in China’s Orbit

In Laos, a new $6 billion rail line is driving rapid social and economic changes — and bringing China ever closer.

Words | Cai YiwenPhotos | Wu Huiyuan

Just a decade ago, the land to the east of downtown Vientiane was a patchwork of lush green fields. Now, a vast, gleaming rail station looms over the landscape — and a new city is rising around it.

The countryside is now dotted with newly built warehouses, business parks, and high-rise apartment complexes — a sign of the Chinese investment that is transforming this once-sleepy Southeast Asian capital.

Laos, a remote nation of 7 million people, used to be known in the region for its mountainous scenery, Buddhist temples, and laid-back lifestyle. But that is rapidly changing as the country becomes a key partner in China’s ambitious Belt and Road Initiative.

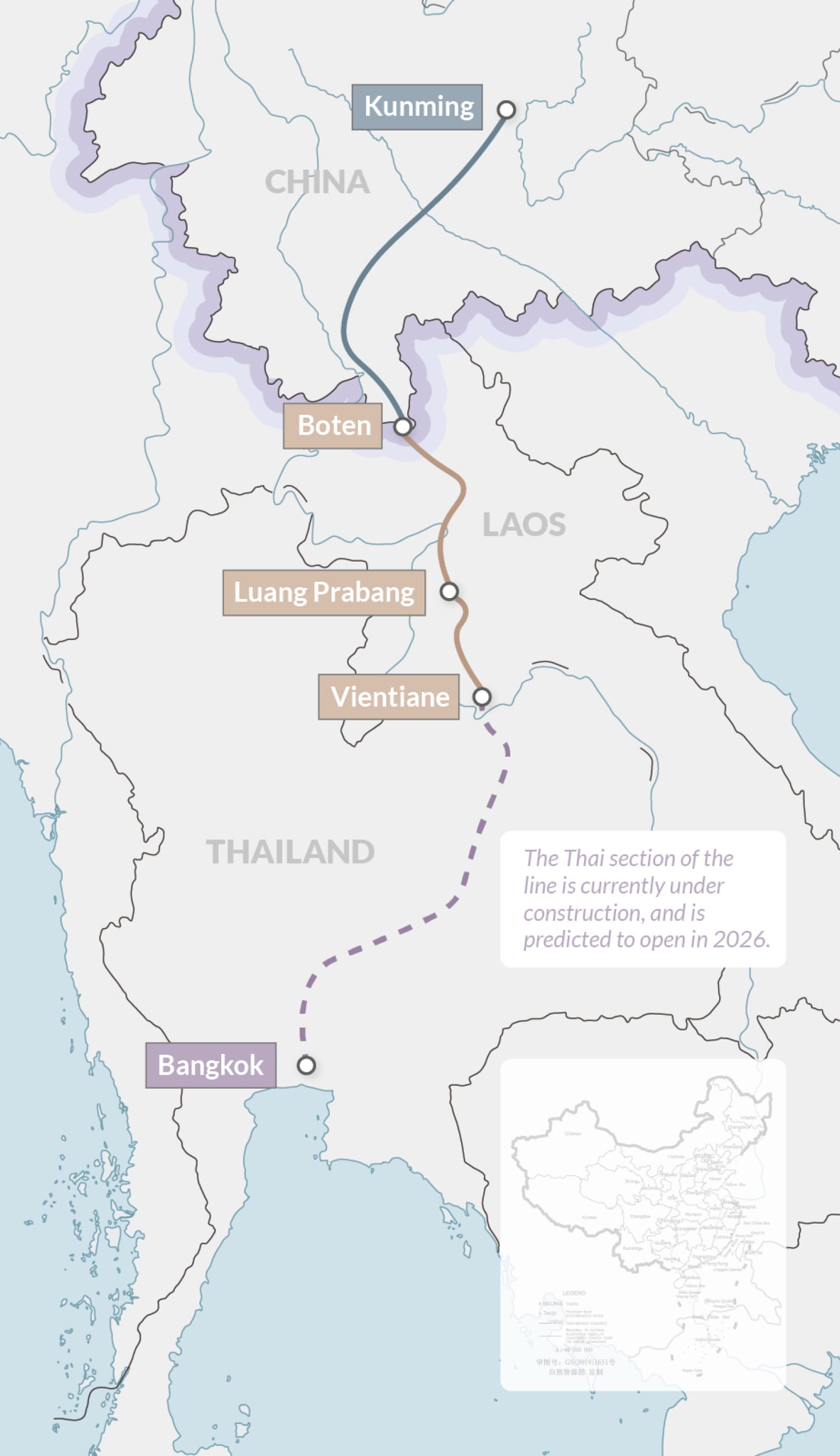

In April, cross-border passenger services began on the Laos-China Railway: a new 1,000-kilometer rail line running from Vientiane to the southwestern city of Kunming. It is Laos’ first semi-high-speed railway, as well as the first international line connecting to China’s high-speed rail network.

Both countries have a lot riding on the project. For China, the LCR is a high-profile test case for its global infrastructure-building program. It’s designed to be the first stage of a long-planned pan-Asian rail network that will run all the way from China to Singapore, via Laos, Thailand, and Malaysia.

For Laos, the stakes are even higher. The country has long championed the LCR, believing it will help the country break out of the economic constraints imposed by its rugged terrain and lack of a natural sea border.

If things go to plan, Laos will become a central cog in an emerging Southeast Asian transport network, transforming it from a landlocked to a “land-linked” economy. The boost to trade, investment, and tourism could raise income levels in the country by over 20%, according to the World Bank.

But the $6 billion project is also hugely expensive. Though China provided most of the funding, taking a 70% stake in the railway, the cost is still daunting for Laos — a country with a gross national product of just $15.7 billion.

The pandemic has made things even harder, as it tanked Laos’ tourism industry and sparked a crippling inflation crisis. The Lao government has already cut back on health and education spending.

Now, Laos is more dependent on Chinese investment than ever. To many in Laos, China represents the only way out of the current slump: a source of desperately needed capital, tourist spending, and white-collar jobs.

The opening of the railway — combined with China’s recent exit from its “zero-COVID” policy — is bringing Chinese businesspeople and tourists back to Laos. But will it be enough for the country to get back on track?

In this series, Sixth Tone travels across Laos to explore how the new railway is impacting the lives of local people — and what it might mean for the country’s future.

In a Post-COVID Laos, China’s Influence Grows Ever Larger

A new $5.5 billion railway is bringing a flood of Chinese investment to the Lao capital of Vientiane. After COVID-19, it’s desperately needed.

Laos Is Desperate for More Tourists. Can a New Railway Provide Them?

Laos’ tourism sector suffered a devastating contraction during the pandemic. Now, the country hopes a Chinese-built railway can drive a revival.

On the China-Laos Border, a Cautionary Tale of Hot Money and Wild Dreams

Chinese investors have poured money into the small Lao town of Boten, believing a new railway would bring massive growth. But the hoped-for boom has yet to arrive.