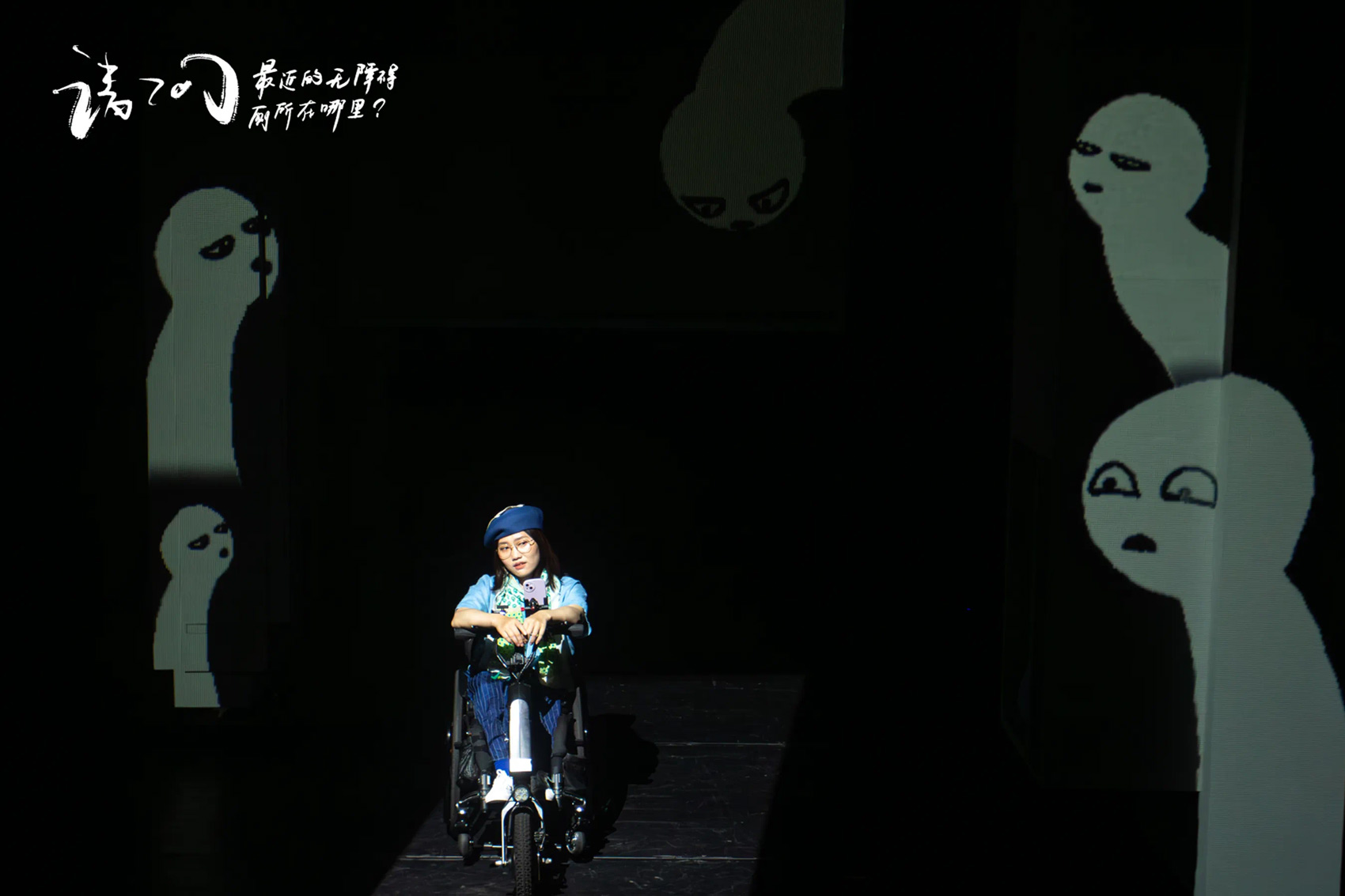

On Stage and in a Wheelchair

The spotlight shined down on a young woman in a wheelchair as she launched into her monologue. “Why do I sometimes have to act weak for people to think I’m normal?” she asked. “Why do I sometimes have to act stronger than others for people to think I’m normal? What even is normal?”

Shen Lujun, the show’s producer, kept a careful eye on the proceedings. “Be Seen” — the first domestic theater production in China to be told from the perspective of someone with a disability — had a successful run in Shanghai in May, but in that moment, Shen was nervously waiting to see if it could replicate that success in its second run, at Beijing’s Tianqiao Theater.

“Be Seen” stands out, not just because of star Zhao Hongcheng, a nonprofessional actor whose life inspired the play, but also for the honesty of its story, which boldly tackles the experiences and confusions of millions of Chinese. (The show’s approach to the subject is evident from its Chinese title, “Excuse Me, Where’s the Nearest Accessible Toilet?”)

The one-woman show draws heavily from Zhao’s life and social media account. A full-time content creator on the video platform Bilibili, Zhao has longed used that site to share snippets of her life as a person with a disability. Sometimes, that means making videos about falling in love or getting a degree. Other times, she’ll share glimpses of venues that advertise discounted tickets for the disabled but cannot admit them; being told to use a diaper by staff at a theater without accessible bathrooms; or a driver of a barrier-free bus who doesn’t know how to use the vehicle’s wheelchair ramp.

Shen, the producer of “Be Seen,” came across Zhao’s account in late 2022, after a leg injury that left her housebound. Gradually, she began thinking about how to bring Zhao’s story to the stage, with the goal of using art to present Zhao’s struggles to a wider audience.

The pair first arranged to meet in a café, Shen arriving on crutches and Zhao in her wheelchair. As they talked, Shen had the idea of making it a one-woman show. The decision was informed as much by practical requirements as artistic vision: There were simply no professional actors in wheelchairs for them to cast.

Before rehearsals began, both director Luo Qian and playwright Chen Si’an tried using a wheelchair. Luo told me her main takeaway was that “The world looks very different from a wheelchair.” That became a mantra of sorts for “Be Seen.” The team didn’t want to make another public service notice about the lives of disabled people; rather they hoped to dramatize their perspectives, feelings, and engagement with the world. People with disabilities would be the subject of “Be Seen,” rather than an object of sympathy.

The choice to cast Zhao as herself came with its own challenges. That was especially true for Chen, the playwright. In producing the first draft, Chen told me she purposefully downplayed topics and even lines she thought might hurt Zhao, resulting in a generic script. In the process of subsequent rewrites, however, she was impressed with Zhao’s bravery, as well as her openness and trust in the entire creative team — a trust that allowed them to tackle topics that she previously considered untouchable.

The crux of “Be Seen” is the second act. After a relatively lighthearted opening, the play moves away from humor and begins to delve deeper into the themes like the human body and shame. Zhao speaks about her own experiences and those of many people with disabilities, including both the rejection of their disabled bodies as well as their own attempts to return to a “healthy and whole” body at all costs.

In the show, Zhao shares how her body and soul had been broken, and how the process of reconstructing herself from the debris was difficult and lonely. Through it all, her greatest source of shame wasn’t the social stigma attached to her disability, but her own family’s continued identification of her as a patient. It wasn’t until after she experienced significant physical and psychological pain that she was finally able to truly accept her body and understand that “disability is not a disease, but can be parallel to ‘normal’ life.”

For Zhao, her mission is clear: To convince the public to stop treating disability as a disease and bring more attention to the lives and stories of people like her. There are 85 million people with disabilities in China, but the population is easy to overlook. In interviews and press engagements, Zhao has repeated the same message over and over: This isolation cannot continue. People with disabilities want to feel integrated, to be a part of normal life, and to feel seen.

The efforts of the “Be Seen” team seem to have paid off. In late May, the show ran for eight performances at the Shanghai Grand Theater, where it’s earned a sterling 8.7 on the notoriously hard-to-please review site Douban. Early reviews of the show’s recently concluded Beijing run were even more ecstatic.

“Be Seen” has succeeded by walking a fine line between qualities that may at first seem incompatible — gentleness and toughness, privacy and frankness, the individual and the public. Illuminated by a beam of light, Zhao shares snippets of her life, but it’s not just her voice and story. “If I was the Little Mermaid, I wouldn’t have given up my voice for anything,” she declares. It’s a perfect summary of what the show is all about.

Translator: David Ball; editor: Wu Haiyun.

(Header image: A stage photo for “Be Seen.” Courtesy of the production)