Tracing the History of Shanghai’s Waste Management

Editor’s note: Waste sorting became mandatory for households in Shanghai in the summer of 2019. The Paper recently looked back at the city’s long history of waste management, tracing the evolution in its practices and the issues it has faced.

As an urban area grows, so too does the amount of garbage it produces, making sanitation one of the most important tasks for any city. Shanghai’s transformation from modest county seat to modern metropolis began in 1843, when its port was opened to foreign trade. Since then, over the past 180 years, waste management in the city has had to change with the times.

Early days

From the opening of Shanghai’s treaty port until its liberation more than a century later, most of the waste produced by the city’s homes and businesses was transported by rickshaw and boat to the suburbs for disposal. The aim was simply to get rid of it, but there was essentially no official guidance on how this got done.

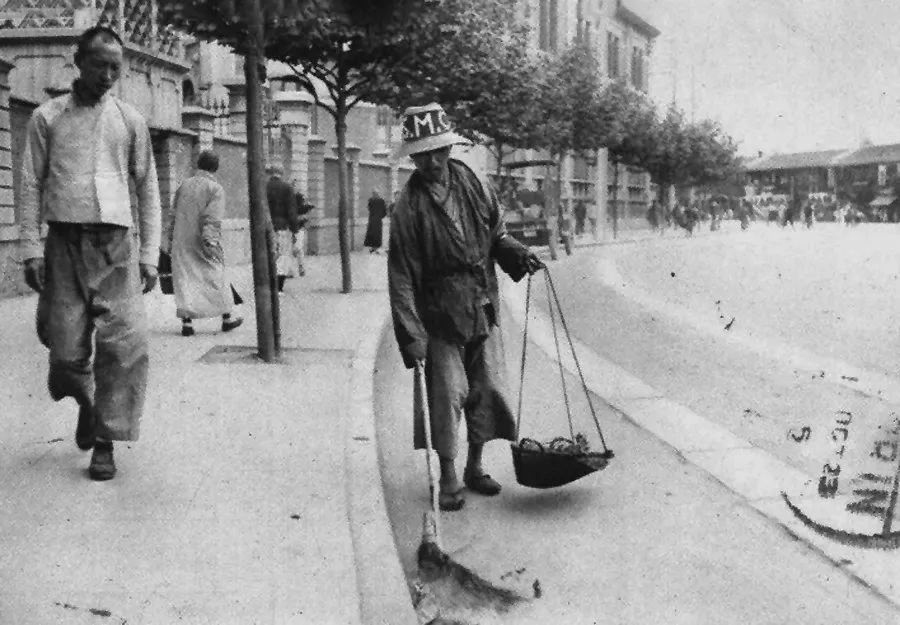

When Shanghai was forced to open its port to foreign trade in 1843, the so-called “great powers” — the U.K., France, the U.S., and others — began to carve out concessions for themselves within the city, and urbanization rapidly accelerated. From the 1860s until the early 1900s, this expansion and population growth led to a huge increase in household waste, attracting the attention of city officials. As a result, the then International Settlement, a merger of the British and American enclaves, decided to employ special workers to sweep its streets and lanes, while responsibility for street cleaning in the rest of Shanghai fell under a special bureau. This marked the establishment of the city’s first professional street cleaners.

With an ever-growing population, and an inevitable rise in the amount of waste produced, the frequency of street cleaning in the then International Settlement was gradually increased from once to twice a day, and three or four times a day in busy areas. In addition, as residents tended to dump their waste at the entrances to alleyways or on the roadside, creating unsightly and unhygienic heaps of garbage, the Municipal Council — a committee of Western businessmen — organized for bins to be placed near residents’ homes. The rudimentary garbage carts that picked up the trash were fitted with bells, so that they would alert people as they passed by.

In 1946, the city’s sanitation department introduced a set of measures on waste collection, stipulating that in the downtown area — bounded by Zhongshan Road in the north, Huangpu (now the Bund area) to the east, Xujiahui to the south, and Huashan Road to the west — a bell would be rung once a day and all garbage had to be disposed of at that time. Anyone who violated the rules would be subject to fines, detention, and even having their power disconnected. Right up until the early 1960s, areas where garbage trucks had difficulty accessing and where it was inconvenient to place communal trash cans still rang a bell to notify residents to dispose of their garbage.

After Shanghai’s liberation, in the 1950s, farmers began to use waste produced in the city as fertilizer. However, the waste suitable for this — organic matter such as vegetable leaves, fish, poultry giblets, and coal ash — was being mixed up and transported along with unusable materials like coal from tiger stoves and industrial waste. This meant farmers first needed to sift through the refuse themselves.

In October 1955, parts of the city tried asking people to separate out waste that was suitable for use as fertilizer. Several areas even made it compulsory and installed separate bins, but various limitations meant the practice was never widely adopted.

Reform and opening-up

When China launched its wide-reaching economic reform policies in the late 1970s, Shanghai entered another period of dynamic and rapid development. Yet, while nearby cities and provinces previously were willing to accept its waste, this was no longer the case, so from 1985 to 1992 Shanghai constructed two landfill sites in its suburbs.

Agricultural production in China began to advance quickly in the 1980s, with a shift toward farmers using more chemical fertilizers rather than making their own by recycling food waste (they did this by sifting through piles of household waste by hand, not only dirty and laborious work but also hazardous, as the waste would often contain broken glass, jagged metal, and other sharp objects).

However, authorities still wanted household waste to be recycled, to reduce the burden of disposal. So, in June 1984, Xinhua Subdistrict in Changning District attempted to introduce waste sorting, stipulating that residents must separate out food waste to be sent to villages to be used as fertilizer, and requiring construction waste to be left at designated points for sorting and removal. The following year, the Shanghai sanitation department decided to pilot the program in a subdistrict of each district. Unfortunately, most of the waste became mixed up again when it came time to transport it by ship, and so the program was soon scrapped.

Putuo District took the lead in launching a new pilot program in its Caoyang Subdistrict in 1987 after residents reported that the on-street garbage bins were attracting flies. It told locals to seal their trash in plastic bags and dispose of it in communal bins that were unlocked only at specific times. Huangpu District followed suit, building hundreds of cement receptacles in its densely populated alleyways, sealing them off between 9 a.m. and 4 p.m. and regularly emptying them at night. By 1989, this method had been implemented in 51 communities across the city covering 51,500 households, removing about 36 tons of garbage per day.

By 1992, roughly 60% of the 800,000-plus households that used gas in Shanghai were taking part. Two years later, the figure was 70%.

Special classification

Shanghai continued to explore the classification, collection, and treatment of household waste, and in 1996 included sanitation reform in its ninth five-year plan for environmental protection. This marked a shift away from the narrow form of management toward a more comprehensive, society-wide system. Shortly after, Caoyang New Village in Putuo District began to pilot a new type of garbage disposal area for residents, using red bins for hazardous waste, yellow bins for inorganic waste, and green bins for organic waste.

Later, the waste classification work focused on the recycling of glass and batteries. In 2000, as one of eight pilot cities for sorting waste, Shanghai launched projects in 100 residential communities to promote garbage classification in incineration areas, and adjusted the classification of “organic and inorganic waste” to “dry and wet waste.”

As the city prepared to host a high-level Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation meeting in 2001, authorities issued a set of requirements to improve Shanghai’s appearance, including new waste classification instructions for hotels, scenic spots, and streets and residential areas around the meeting venue. Where possible, communities set up biological treatment stations for the onsite disposal of residents’ kitchen waste. By that December, more than 30% of central urban areas were sorting their trash, 75 demonstration communities had been set up for classified collection, and 39 biological treatment stations for organic waste had been built. The following year, more than 2,000 communities in Shanghai were promoting garbage sorting and collection, covering about 1.5 million households.

On April 1, 2002, Shanghai launched regulations on domestic waste sorting and collection in incinerator service areas, and expanded pilot programs for the disposal of kitchen waste. After two new large-scale household waste incineration plants went into service in Yuqiao and Jiangqiao, about 2,000 tons of waste were being disposed of daily. The energy produced by the incinerators was sold to the power grid, bringing social, environmental, and economic benefits. By this stage, official documents on waste management had become more standardized, and supervision more comprehensive.

In December 2007, 100 residential communities in 19 districts and counties across the city were selected to pilot the classification of domestic waste into four types: hazardous waste, glass, recyclables, and other waste. Government offices, private enterprises, and institutions also began installing colored bins for different types of waste in late 2009: blue (recyclable), red (hazardous), and black (other waste). Around this time, effectively the whole process of classification and logistics was established, with the city setting up 63 transfer points for hazardous waste and glass, allocating 65 special collection vehicles, and sorting out nearly 2% of the total amount of glass, hazardous materials, and recyclables from domestic waste.

Standardizing the system

The Shanghai World Expo in 2010 marked another key moment, with the city government issuing two important documents that identified waste classification as a priority. Around that time, a “green account” incentive was also officially rolled out to encourage citizens to take part in waste sorting by giving them points that could be exchanged for goods and services, while a special group was set up to promote the reduction of waste, led by Shanghai’s Construction and Transportation Commission, Women’s Federation, Civilization Office, and Greening and City Appearance Administration. District authorities took on more responsibility in waste sorting, and the city’s waste management office commissioned external testers to regularly assess pollutant levels at municipal facilities to determine the environmental impacts of the process.

A raft of measures released in 2014 went on to outline the classification standards of domestic waste as recyclable, hazardous, wet, and dry. This marked the official inclusion of Shanghai’s waste sorting onto the statute books.

Afterward, projects such as renewable energy utilization centers and comprehensive landfill sites were built in suburban areas such as Jinshan, Pudong, Fengxian, Chongming, and Songjiang. By the end of 2017, more than 60% of the city’s residential areas were covered by waste sorting services, and about half were offering green accounts to residents. Meanwhile, Shanghai’s hazard-free treatment rate of household waste reached 100%, and it was among the first places to pass the national acceptance of comprehensive treatment of rural waste. In addition, Jing’an and Songjiang districts were named in the first batch of China’s urban waste sorting demonstration areas, and the districts of Fengxian, Chongming, and Songjiang were included on the list of the first 100 rural household waste sorting demonstration zones.

In 2018, Shanghai issued a three-year action plan for the construction of a citywide solid waste classification system, highlighting waste classification as an important task for urban governance and fully integrating it into the city’s overall management plans.

Shanghai is home to around 24.5 million permanent residents and a floating population of more than 5 million, producing a daily average of more than 30,000 tons of waste. This equates to about 1.01 kilograms per person per day, while the amount produced in developed countries is about 1.4 kilograms per person per day. The Shanghai Municipal People’s Congress, the city legislature, officially made waste sorting mandatory in 2019.

The city is now working towards targets set out in its 14th five-year plan for waste classification. By 2025, it aims to sort 95% of household waste, recycle 45% of its waste, maintain a 100% hazard-free treatment rate, and send zero household waste to landfill.

Reported by Feng Jing.

A version of this article originally appeared in The Paper. It has been translated and edited for brevity and clarity, and is republished here with permission.

Translator: David Ball; editors: Xue Ni and Craig McIntosh.

(Header image: A sanitation worker pedals down the street in Shanghai, October 1998. Joe McNally/Getty Images/VCG)