How a Red-Haired Chatbot Became China’s New Favorite English Tutor

At his home in Shanghai, third grader Vincent is having his weekly English class via a FaceTime call with an American woman named Annie.

“Hi Annie, do you know the Harry Potter books?” the child asks. Annie, a pale figure with wavy red hair, blinks and nods as she listens to Vincent, before responding.

“This is a famous fantasy novel series by J.K. Rowling that tells the adventures of a young wizard, Harry Potter, and his studies and upbringing at Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry,” she says. “Have you read them or seen the movies?”

The woman is not a real English tutor, but an artificial intelligence-generated avatar from the app Call Annie — a service that allows users to talk with a ChatGPT-powered bot via FaceTime. Vincent’s mother, Yuki Zhang, began using the app to help her son practice English soon after it launched earlier this year.

“Foreign English tutors cost at least 350 yuan ($48) per session and don’t offer flexible time slots,” says Zhang. “But Call Annie is free and always available.”

Zhang is far from alone in doing this. Call Annie has unexpectedly become a sensation in China in recent weeks, as Chinese parents swap tips on how to turn the chatbot into a makeshift English tutor for their children.

China banned private academic tutoring — including English tutoring — in 2021, aiming to reduce the intense pressure on students. But many parents worry that their children will be unable to achieve fluency in English without extra tuition. (Research suggests that English proficiency levels are trending downwards in China.)

Families have been using a number of workarounds to give their kids extra English classes: using language learning apps, teaching children themselves, or taking them to black-market tutoring firms.

Now, many are turning to generative AI products like Open AI’s ChatGPT. On Chinese social media, posts sharing tips on how to train AI chatbots to act as language tutors have frequently gone viral in recent months.

Call Annie, an app created by the Silicon Valley developer Animato Inc., has emerged as a particular favorite among Chinese users. The software effectively allows users to talk to ChatGPT via a FaceTime call, with its red-haired avatar able to listen to and answer questions in real time. It can be used free of charge, but there is also a premium version featuring extras such as tailored language lessons.

The app isn’t easy to access from China: It not only requires using an iPhone, but also an overseas Apple ID and the latest version of iOS. But users say it offers the best English learning experience, as Chinese AI bots such as Baidu’s Ernie system have mainly been trained using Chinese-language — rather than English-language — materials.

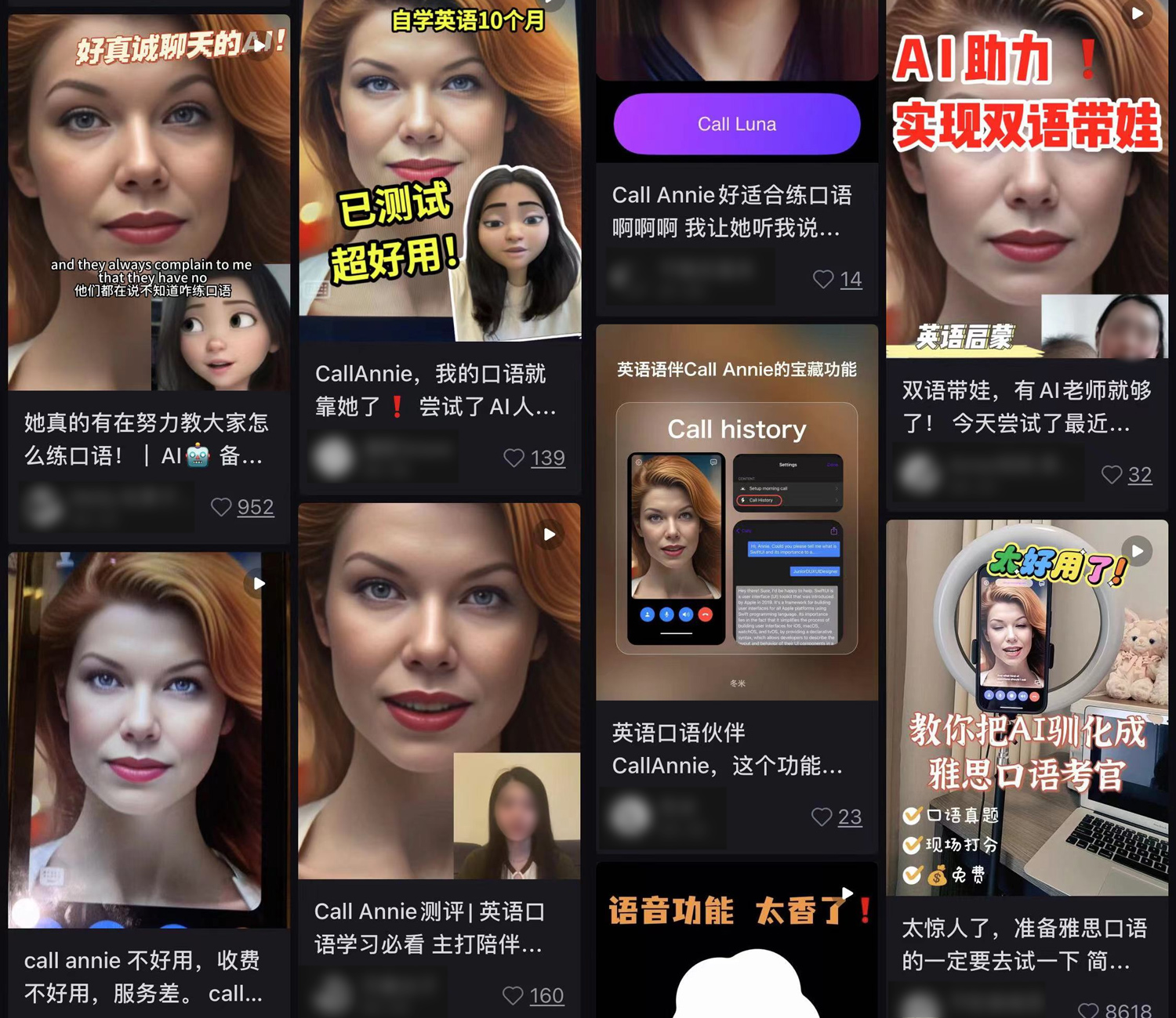

It’s unclear exactly how many Chinese users Call Annie has, but the hashtag #CallAnnie has received more than 1.3 million views on Xiaohongshu, China’s closest equivalent to Instagram. Videos offering tips on how to use Call Annie to pass the IELTS — a high-profile English language proficiency test — have received thousands of likes on the platform.

Hou Mengtian, a 30-year-old freelancer in Beijing, says she was astonished by Call Annie’s verbal features when she began to use the app to prepare for the IELTS a few months ago.

After Hou explained her requirements, Annie was able to play the part of an IELTS examiner — not only generating English speaking tests for Hou, but also assessing Hou’s performance and providing feedback based on the IELTS curriculum.

In one such mock test, which Hou recorded and posted to Xiaohongshu, Annie challenges Hou to introduce her hometown. After she has finished, the bot tells her:

“You provided a clear and concise answer to the question. You spoke fluently and demonstrated your ability to communicate basic information about your hometown and current place of residence. Based on your performance, I would give you five out of nine for this part of the test.”

According to Hou, these exercises made a real difference to her studies, allowing her to identify the areas where she needed to improve. She has since become an evangelist for Call Annie, with her tutorial for using the app racking up more than 8,000 likes on Xiaohongshu.

“Talking to Annie exposed my greatest weaknesses in the speaking test, such as nervousness and lack of vocabulary,” says Hou. “It allowed me to put more effort into these areas.”

Generative AI systems like Call Annie still have their limitations. Despite the hype since ChatGPT’s launch last year, experts say that language teachers don’t need to worry about being replaced by AI any time soon.

“Human tutors can understand students’ struggles and thus provide emotional encouragement, but AI chatbots may be unable to do so,” Timothy Hew, a professor of human communication, development, and information sciences at the University of Hong Kong, tells Sixth Tone. “Also, they can explain cultural contexts and language nuances better than AI chatbots, which is essential to learning a language well.”

But AI tools are proving especially useful for people who have no access to — or who can’t afford to hire — a foreign language tutor. Qu Xiaotong, a law student at the University of Washington, has been polishing her English using a combination of ChatGPT and Call Annie.

Qu’s four-step system, which she shared via Xiaohongshu, involves watching a TED talk and jotting down key phrases to study; asking ChatGPT to generate a list of explanations, sample uses, pronunciation guides, and Chinese translations for each of those key phrases; creating a list of questions to discuss based on those phrases; and then discussing the questions with Call Annie.

“Even if you lack an English-speaking environment, you can still practice spoken English using AI chatbots,” Qu says. “It’s even more effective because you can discuss a specific topic and get feedback on grammar and expressions.”

Zhang, meanwhile, particularly likes that Annie can learn from previous conversations and adapt to users’ preferences. She usually encourages Vincent to practice his spoken English with Annie by discussing the English books he has read recently, and she appreciates the bot’s growing ability to keep the conversation flowing. Annie will now often proactively ask questions to keep her son engaged, such as “Who is your favorite character?” and “Why do you like that character the most?”

“Because Annie is AI-generated, Vincent talks more freely as he feels less stressed about his mistakes and fluency,” Zhang says.

For China, however, the growing use of Call Annie could have worrying social implications, Hew says. The app is undoubtedly an effective tool for learning English, but in practice the majority of families will be unable to access it. This could exacerbate inequality by handing children from wealthy, well-connected families a key advantage.

But Krissy Jiang, an English teacher at a public elementary school in Tianjin, stresses that any parent can help their child master English if they are committed enough. In her view, English lessons in the classroom are not enough; neither is using ChatGPT. Instead, the key is fostering an immersive language environment in which a child can use their English on a daily basis.

A mother to an 18-month-old daughter, Jiang has insisted on speaking to her child in English whenever possible. She mainly uses Call Annie to help her achieve this, such as by asking her to suggest natural-sounding English expressions that she can use in specific scenarios.

Before a recent visit to the park, Jiang asked Annie: “What phrases could I say if I took my baby girl to play on the swing?” After the bot suggested a series of phrases like “Do you want to play on the swing, sweetie?” and “Let’s go have fun on the swing,” Jiang tried to use these expressions whenever possible.

“It’s up to parents to create a more immersive English environment for kids,” she says. “There are more resources to learn English in 2023 than in the past. Kids can excel as long as parents help kids practice.”

Editor: Dominic Morgan.

(Header image: Visuals from Call Annie, jossdiim/VectorStock, and Wavebreak Media/VCG, reedited by Sixth Tone)