Fuchsia Dunlop on the Past, Present, and Future of Chinese Food

Fire-exploded kidney flowers might seem like odd fodder for an epiphany — the spicy, offal-heavy dish is uncompromising, even by Chinese standards — but for chef, food writer, and cookbook author Fuchsia Dunlop, they bloomed into a lifelong passion for Chinese cuisine.

“This was a dish that was so unlikely to me,” she recalls thinking.

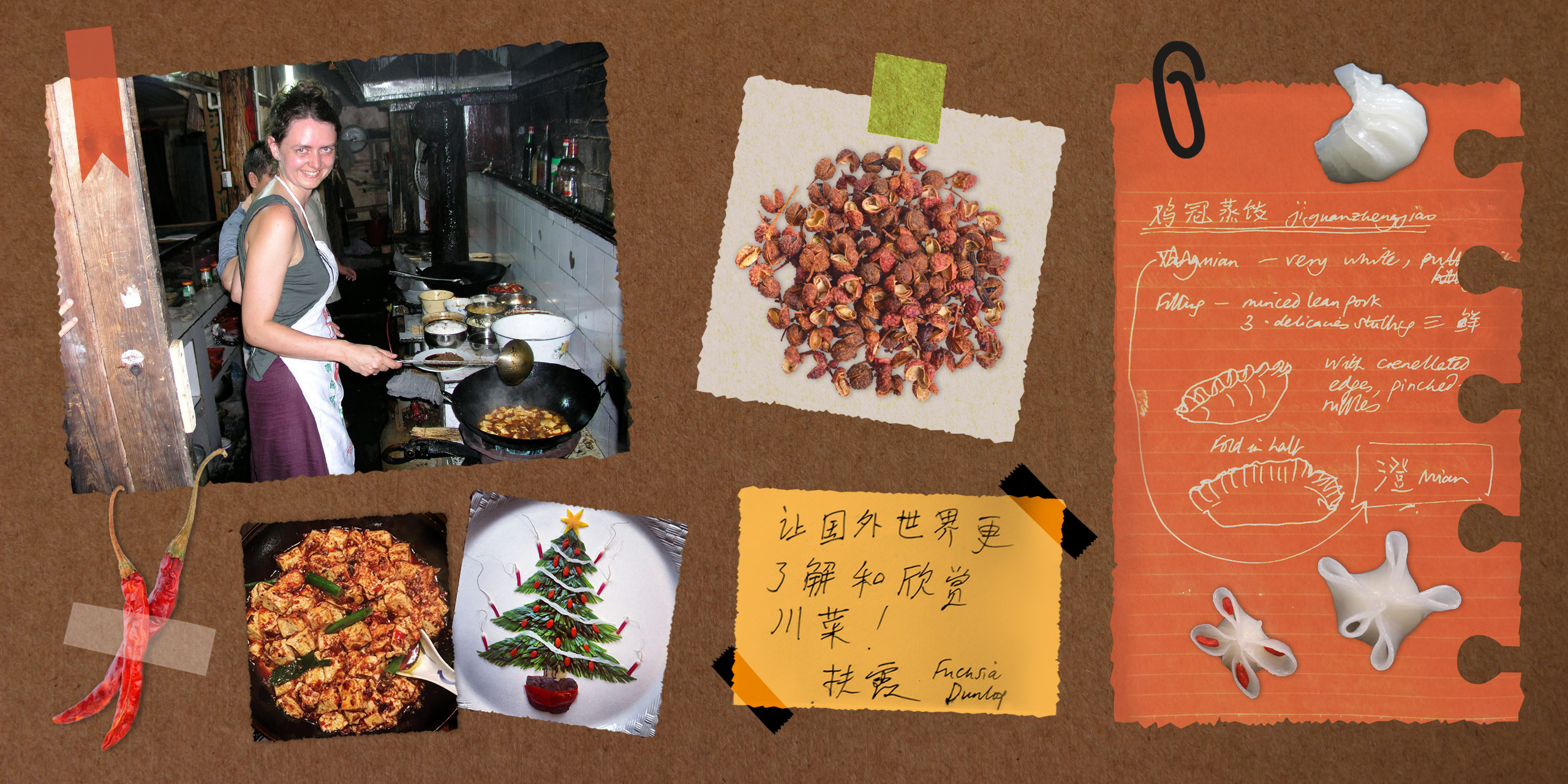

Today, she’d barely bat an eyelash at the ingredient list. After a stint at the Sichuan Institute of Higher Cuisine in the mid-1990s, Dunlop has become one of the most popular and accomplished Chinese cookbook authors in the world — in any language. She has spent nearly three decades researching, practicing, and writing about Chinese foodways, from the intensely spicy dishes of the southwest to timeless classics from the Yangtze River Delta region.

But her most important skill may be her ability to demystify the unique, unlikely, and unusual. It’s not just ingredients like offal; she is particularly attuned to the subtleties of kougan, or mouthfeel. Terms like slithery, crunchy, or gloopy are rarely compliments in English, but they’re prized components of many of China’s most famous dishes, a conceptual gap at the source of many misperceptions of Chinese cuisine. If you don’t understand kougan, how can you understand why Chinese go to such great lengths to cook and consume foods like duck tongue?

Now, Dunlop is setting her sights on another often-misunderstood side of Chinese culinary culture: the banquet table. In “Invitation to a Banquet: The Story of Chinese Food,” she musters her almost 30 years of research and experience to systematically examine the culture, history, and philosophies underlying Chinese gastronomy, from hearth and farm to kitchen and table.

This October, Dunlop sat down with Sixth Tone over Zoom to talk about her new book, why Chinese food is so misunderstood, and what the future might hold for the country’s cuisine.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Sixth Tone: You’ve published eight books about Chinese cuisine, each of them with its own focus and purpose. What was your goal in writing “Invitation to a Banquet”? Why focus on banquet culture this time?

Fuchsia Dunlop: Chinese food has become very popular around the world. But people in the West often don’t understand its sophistication. In fact, many ideas in modern Western gastronomy have ancient parallels in Chinese cooking. For example, we often talk about terroir. Chinese gastronomy puts a lot of value on where foods come from and how they are grown. Nowadays imitation meats made from plant ingredients are quite popular in the West, but in China, they can be traced back to the Tang dynasty (618–907).

That is why I chose “Invitation to a Banquet” for the title. Because a banquet is a huge feast for which you need lots of sophisticated preparation. Also, China has a very strong food culture, in which foods are closely connected with rituals and social order. For instance, during the rites of sacrifice, people use foods to connect with their ancestors. This was also the case at the state level before China’s last dynasty was overthrown in 1911. Families still make offerings to their ancestors, even now. Chinese people take enormous pleasure in food. You can find many descriptions of foods and drinks in Chinese traditional poems and literary works.

Sixth Tone: What are some of the common misconceptions about Chinese food in the West, and where did they come from?

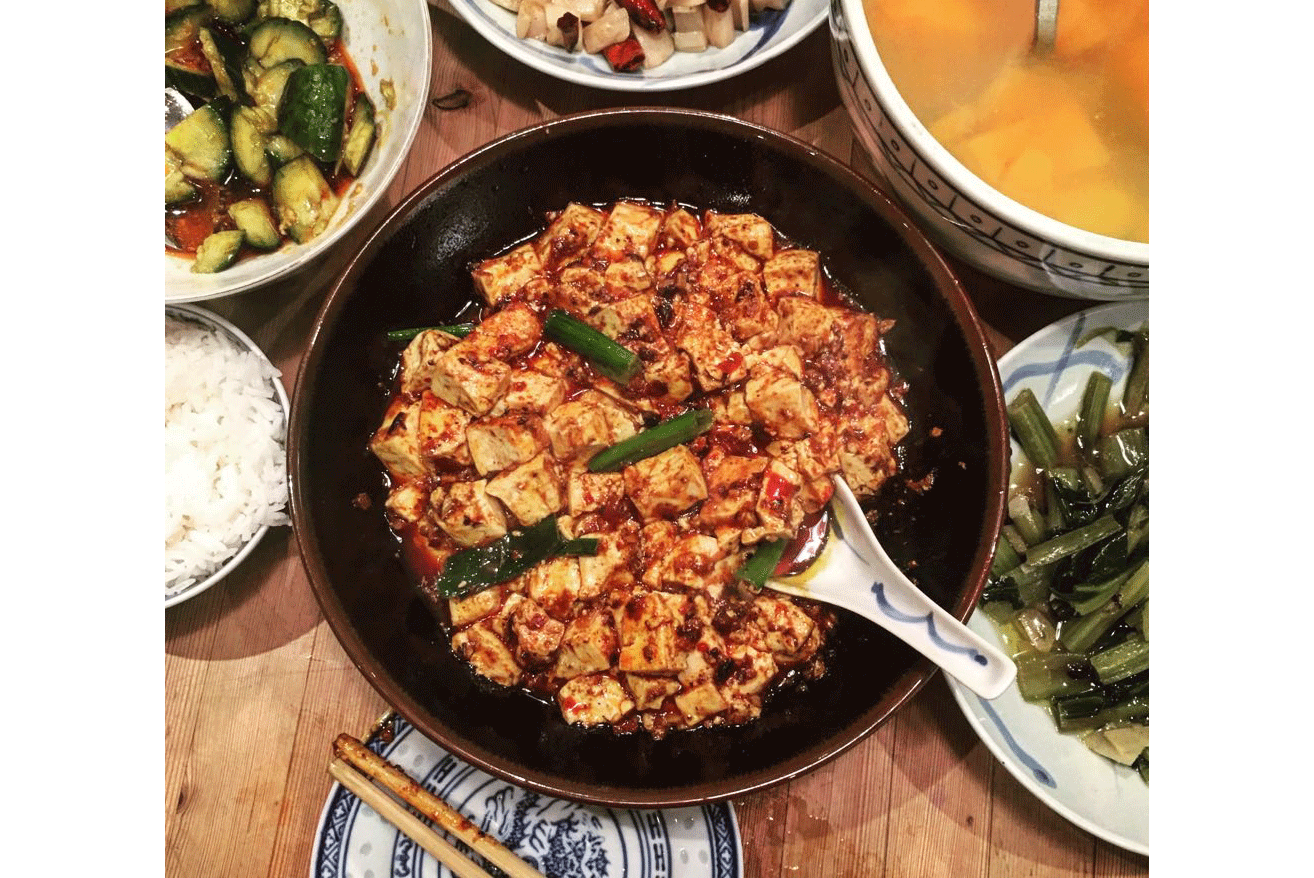

Dunlop: A common misconception is that Chinese food is cheap. It is widely seen as unhealthy, and often simplified as adapted Cantonese cuisine. Some also think of Chinese cuisine as kind of alien, because the Chinese use all kinds of unfamiliar ingredients like internal organs or chicken feet, and their food is often cut into small pieces, which can make ingredients unrecognizable.

The background to these misperceptions is both racial prejudices and unfamiliarity with Chinese culture. Although notes from missionaries who traveled to China in the 17th and 18th centuries were complimentary of Chinese culinary skills, the tone of later European adventurers became more hostile, portraying Chinese as filthy eaters in a broader attempt to discredit them, even as they sought to exploit the lucrative Chinese market. Such racial prejudice still exists today when people talk about Chinese foods.

Popular impressions of Chinese cuisine are also influenced by immigrant history. Many early Chinese immigrants were from a particular area: the Cantonese south (Guangdong). The vast majority took jobs in the Chinese catering industry, which was hugely successful. But they didn’t have a rich array of ingredients at their disposal, and their food needed to be accessible, cheap, and only mildly exotic.

The fact is, Chinese cuisine is highly sophisticated and chefs are hugely inventive, using clever culinary techniques to transform unlikely ingredients, like tasteless jellyfish or pomelo pith, into delicious dishes. In other cultures, these things are discarded. And at a time when we all need to be more inventive, because eating as we do now, with so much meat and fish, is unsustainable, I think chefs in the rest of the world have a lot to learn from China as they attempt to create appetizing dishes from, for example, insects as a potential source of protein.

Also, for the Chinese, good food is not just about taste, but also whether it is good for your health. One key to understanding Chinese gastronomy is yaoshi tongyuan, which means food and medicine come from the same source. The idea of what is good food has been mixed up with medicine from the beginning in China. Some of the earliest recipes are found on medical prescriptions in manuscripts from the Mawangdui site in Hunan province. (Editor’s note: Mawangdui is the site of three grave mounds dating to the first or second centuries B.C.)

The Chinese diet is about the whole system, and balance is critical. For example, if you have some very rich and heavy dishes, you need to have some light dishes at the same meal. This is not the case in, for example, British cuisine, which doesn’t see foods as medicine in the same way. So it’s very distinctive.

Sixth Tone: In the book you feature 30 dishes, each of which is given a chapter. In addition, there are a huge quantity of historical materials in the book. I’m curious how you collected all the materials, and how you chose these dishes.

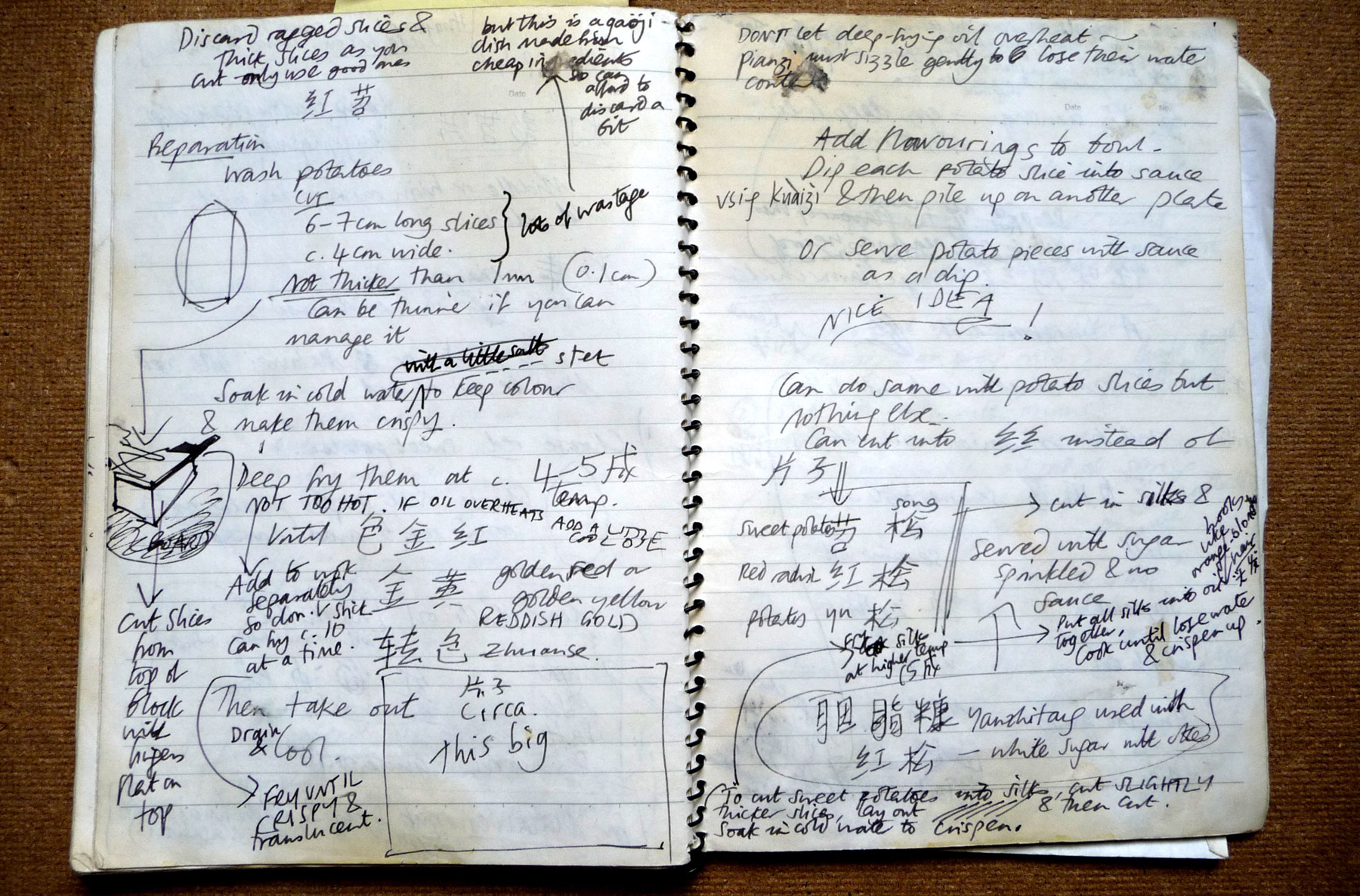

Dunlop: Actually, when I started writing this book in 2021, I already had much of the material I needed in my 150 notebooks going back about 30 years. One exception was xiazi youpi (braised pomelo pith with shrimp eggs). I’ve eaten this dish many times, and I love it, but I didn’t know how to cook it. I was planning to go to Hong Kong, but because of the pandemic, I couldn’t. So a friend of mine in Hong Kong arranged a dinner in a restaurant, and made a video with the chef explaining how to make it.

I chose the dishes I did for this book to make certain points about Chinese cuisine. For example, for the chapter about the amazingly resourceful creativity of Chinese cuisine, I used braised pomelo pith with shrimp eggs, because it perfectly expresses the theme that you can take anything and make a good dish out of it. Or similarly, when it came to the idea of grain foods being central to Chinese diets, steamed rice was an obvious choice. With xiaolongbao (steamed ‘soup’ dumplings), I talked about dim sum, as it’s a kind of dim sum that is known around the world, and it says so much about Chinese culinary history.

For many of the themes I cover in the book, there were a lot of choices. But then I was also thinking of the whole book. I wanted to have a real mixture of some very ordinary dishes and some very expensive dishes; different ingredients, different regions.

Sixth Tone: You just returned from a trip to China in September. Have you observed any new trends in Chinese ways of eating or cooking since the pandemic? For example, delivery foods and yuzhicai (pre-prepared foods made in central kitchens) are everywhere now. How will these new trends change China’s food culture?

Dunlop: On the one side, it is amazing what you can get to go in China; you can get anything. Not just fast foods, but also really healthy stuff. When I was in my hotel, I ordered a black chicken soup in a clay pot that was like a grandmother’s home cooking.

But on the other side, the easy availability of takeaway means that young people will not be cooking as much, and will lose their cooking skills. Even in restaurants, there is less skilled work. With yuzhicai, restaurants are not really training the next generation of chefs well. Also, foods that do not require much skill are prevalent now, like hot pot. With hot pot, you have a restaurant that has a head chef who makes the stock, while others are just cutting vegetables and washing up. Because of all this, foods are simplified, and that’s really sad.

The other negative thing is the packaging. It’s the same here in the West, there is so much plastic being generated by takeaway containers. It’s really appalling from a pollution point of view.

The most shocking and funniest thing I experienced in China this year was having a robot deliver food in a hotel. I just couldn’t believe it when I saw it. A few years before, somebody showed me an automatic stir-fry machine. The chapter about stir-fries ends up asking if this subtle and beautiful art will be done by robots in the future. I don’t have an answer.

Sixth Tone: Did the chefs you met mention any challenges they’re facing?

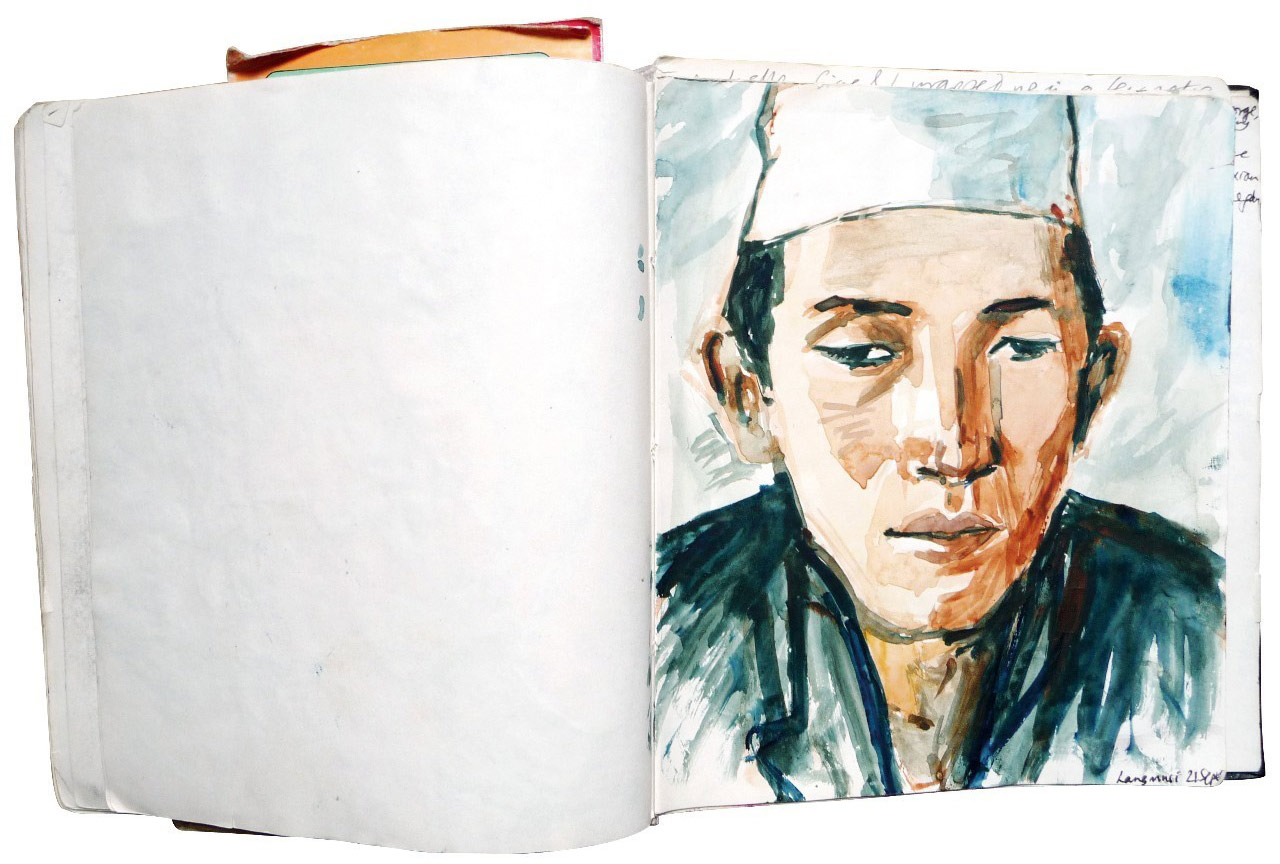

Dunlop: I know some absolutely outstanding chefs in China, and even they find it very difficult to find apprentices. What they say is that young people are not willing to chiku (often translated as “eat bitterness”), that they are not willing to do tough things. But I do understand that it’s tough being a chef, and lots of young people would rather do something easy.

For a lot of the old chefs I know, it was really difficult for them, especially at the beginning. They started when they were very young, maybe when they were teenagers, and they spent years doing menial tasks, like killing fish, washing up, and it’s very hard to learn. I know one senior chef who is very accomplished, but her grandson is going to be a Western chef, because it seems easier.

But lately I’ve met some young people, even people who have been to college, who’ve decided to learn to cook Chinese food and work in traditional food businesses. One young woman I met was educated in America, and she’s gone back to Sichuan to work in her family’s food production business. And I met a young chef in Chengdu who went to college and has since gone back to work with his father in a restaurant. Previously, there was a widely shared belief that cooking is not a very prestigious job. I think that idea is changing a bit. Now you have young people saying, “I want to do this job because I love it.” This used to be a quite radical thing in China.

Also, it’s difficult getting good ingredients. China has industrialized and developed very quickly. Farmland has been developed, there are problems of pollution, and so on. So finding good ingredients is a big challenge for chefs. But on the other hand, some people are now trying to market organic foods, so it’s a process.

Sixth Tone: What are some of the new dishes that you’ve tried to make at home? If people outside China want to make some homecooked Chinese cuisine, what would you recommend?

Dunlop: Recently I’ve been cooking for the first time with taojiao (a kind of peach gum). I keep having it in China, so I’ve been making desserts with that. I was in Yunnan in September, and afterwards, at home, I made some Yunnan rice braised with ham and potato.

For those first starting to make Chinese food at home, I would recommend kung pao chicken. There is a recipe for that in my last cookbook, “The Food of Sichuan.” You cut everything up in small pieces carefully, and then you put each ingredient into a wok in sequence and cook it until stir fried. It’s an easy dish to make, because you prepare everything first, and then you cook it, and it’s always delicious. But it’s very complex too, in the sense that it makes a big difference how long you cook the chili, how hot the oil is, and when you put in the sauce. The more you make it, the more you understand how to make it even better. I still learn something about kung pao chicken whenever I make it, even though I’ve been making it for 30 years.

(Header image: Visuals from Fuchsia Dunlop and IC, reedited by Sixth Tone)