Deciphering Dunhuang

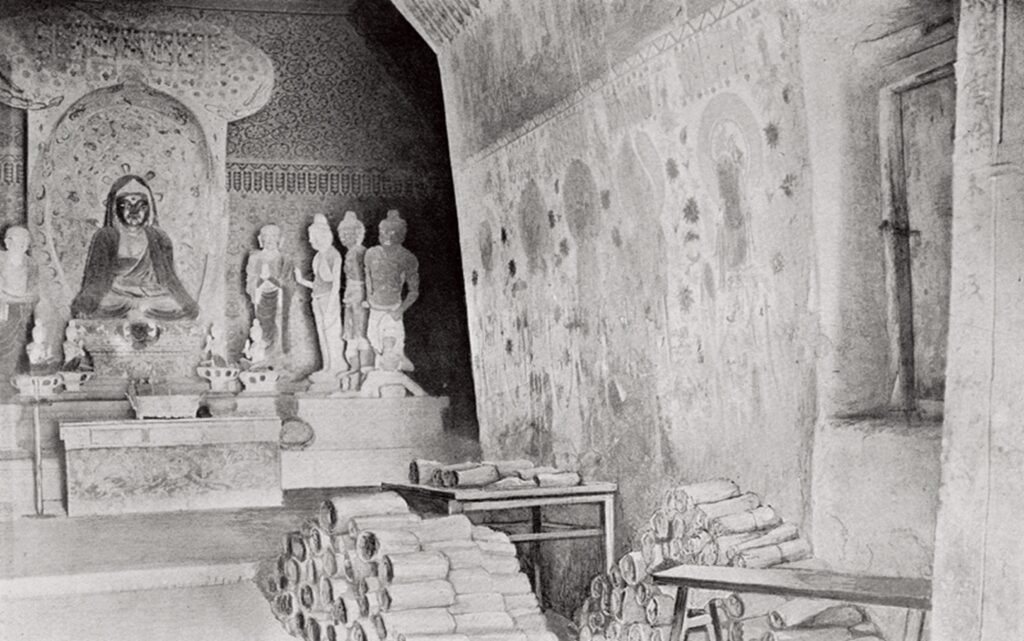

The cave paintings of Dunhuang, a former Silk Road outpost in northwestern China, are spectacular to behold. Bordered on all sides by the windswept desert, these centuries-old masterworks stand testament to the faith and fears of the traders who passed through Dunhuang.

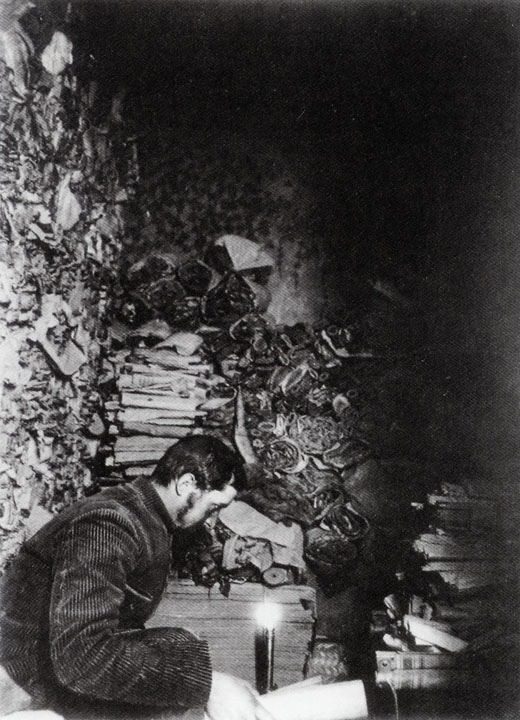

But there was another treasure hidden in Dunhuang: its manuscripts. In 1900, the Taoist monk Wang Yuanlu, a resident of Dunhuang’s Mogao Grottoes, stumbled upon a concealed cave while clearing away accumulated sand. This hidden repository — now known as the Library Cave — yielded over 70,000 artifacts, including Buddhist scriptures, documents, embroideries, silk paintings, and ceremonial objects dating from the fourth to the eleventh centuries.

Wang’s accidental discovery would give scholars new insights into ancient Chinese and Central Asian history, geography, religion, economy, politics, ethnicity, language, literature, art, and technology. However, immersing oneself in the study of the Dunhuang manuscripts today is no easy feat. Almost immediately after their discovery, the treasures of the Library Cave were bought, stolen, or pillaged, a process that has left them dispersed across the world.

This is where scholars like Hao Chunwen come in. Since pursuing his master’s degree in history at Beijing Normal College (now Capital Normal University) in the 1980s, Hao has devoted his career to the identification and transcription of the Dunhuang manuscripts. Since 2010, Hao has headed a major government-funded project to compile and research Dunhuang manuscripts held in collections in the United Kingdom.

During the recent World Conference on China Studies, Hao spoke to Sixth Tone about the current state of Dunhuang studies, the challenges facing the field, and what makes these manuscripts so unique. The interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

Sixth Tone: The ancient manuscripts discovered in Dunhuang are now scattered across the globe. From a research standpoint, the visualization and digitization of these texts are imperative. Can you shed light on the progress being made toward this goal?

Hao Chunwen: Initially, studies of the Dunhuang manuscripts relied on photographs or reproductions printed from photographic sources. Since the 1950s, microfilms of the Dunhuang manuscripts have been successively taken by collections in the U.K., France, and China. However, due to the limitations of photographic equipment and technology during that period, many characters in these films and their subsequent prints appear blurred, significantly impeding the academic community’s utilization of these materials.

In the 1990s, professional photographers began to rephotograph the manuscripts using more advanced equipment. The resulting second-generation black-and-white prints represented a marked improvement over the original versions but still contained some indistinct content. Given that the manuscripts were inscribed centuries ago, some ink has faded, and certain manuscripts are heavily stained, contaminating or obscuring the original text. Such characters are challenging to discern in black-and-white prints.

The recent advent of high-definition color prints and infrared photography has substantially addressed these shortcomings. And thanks to the International Dunhuang Project, color prints of Dunhuang manuscripts from three major collection holders — the Bibliothèque nationale de France, the National Library of China, and the British Library — have been either fully or partially published online.

Regrettably, despite the Institute of Oriental Manuscripts of the Russian Academy of Sciences participating in the IDP, their color prints have yet to be made available online. The further digitalization of Dunhuang manuscripts necessitates international collaboration, the unified efforts of Dunhuang scholars and publishers, and substantial investments in manpower and financial resources. Hopefully, this endeavor can be completed within the next 10 to 20 years.

It’s worth mentioning that, based on my personal experience, if circumstances permit, consulting the originals is optimal. Viewing the first-generation black-and-white prints made from microfilms is akin to walking at night; the second-generation black-and-white prints are reminiscent of walking under moonlight; whereas examining the original documents is comparable to walking in daylight.

Sixth Tone: Even then, deciphering the writing on the manuscripts can be a challenge. What makes it so complicated?

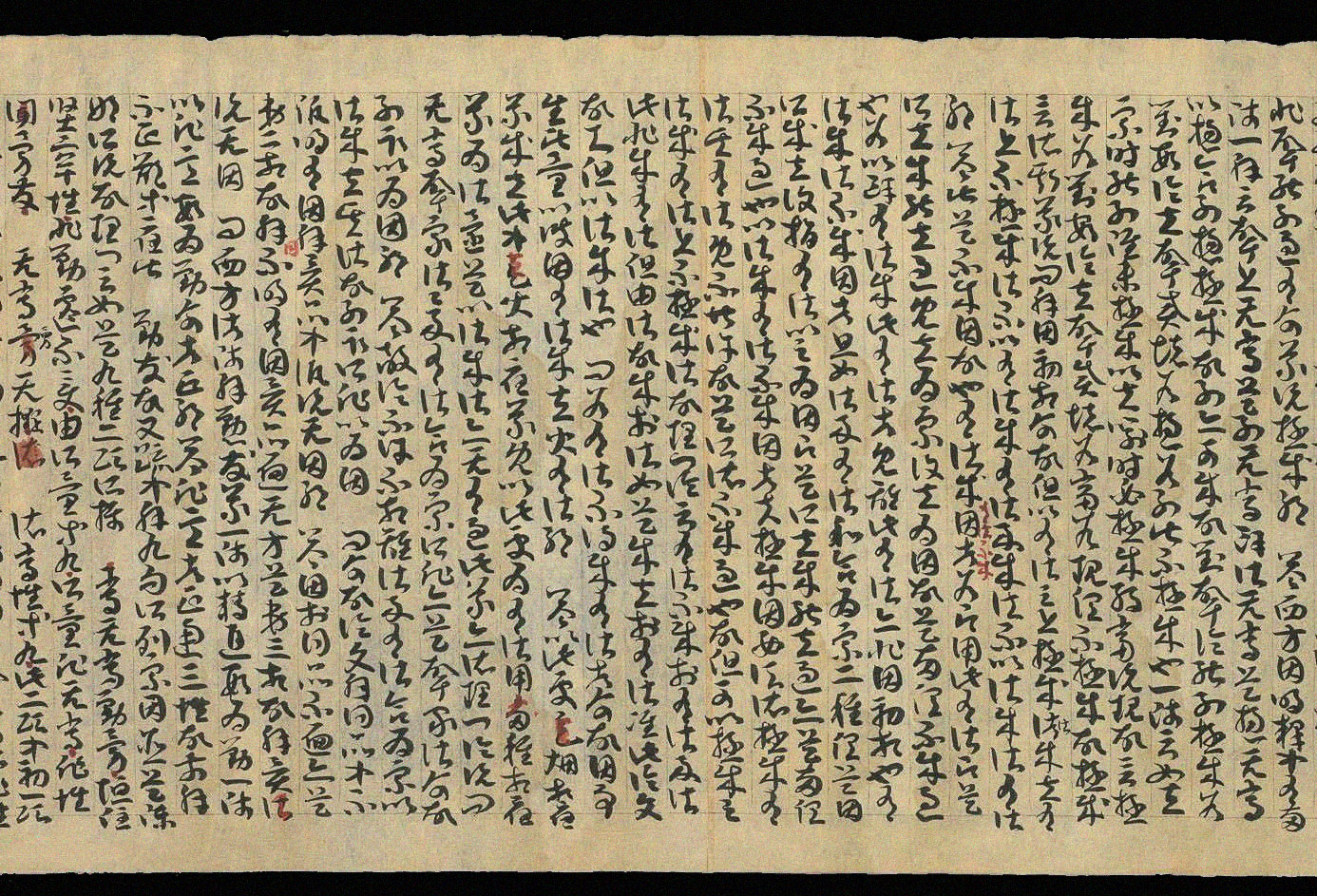

Hao: The bulk of the Dunhuang manuscripts are roughly a millennium old, and the characters on these texts were often written hastily. They also retain many “common” forms of Chinese characters from the era that have since fallen out of use, along with numerous substitute symbols. Due to the prevalence of northwestern Chinese phonetics in the Dunhuang area during the Tang and Song dynasties, many phonetic loan characters in Dunhuang manuscripts differ from those found in general ancient texts. Additionally, some texts are transcriptions of oral Chinese and may feature homophonic substitute characters.

Apart from the texts, don’t forget that the manuscripts themselves are cultural relics. There are many intricacies involved. Ancient people wrote on paper much like today’s people take notes in notebooks. Some individuals wrote on the front of the paper, while the next person might use the back. Traditional Chinese character writing typically proceeds from right to left. However, on occasion, the text in some documents is written from left to right. It took us a long time to realize the direction was reversed.

Sixth Tone: How many scholars capable of deciphering these characters are there in China today? Can computers help?

Scholars like myself will mentor students. Consequently, there are likely over a hundred individuals capable of recognizing these characters to some extent. However, if we’re talking about the highest level, I think there might be only seven or eight such scholars nationwide.

Recognition still relies on humans; computers cannot assist in this regard. Computers are limited to recognizing standard square characters and are unable to read oracle bone inscriptions, characters on unearthed bamboo and silk texts, or those in the Dunhuang manuscripts.

Sixth Tone: What makes the Dunhuang manuscripts unique?

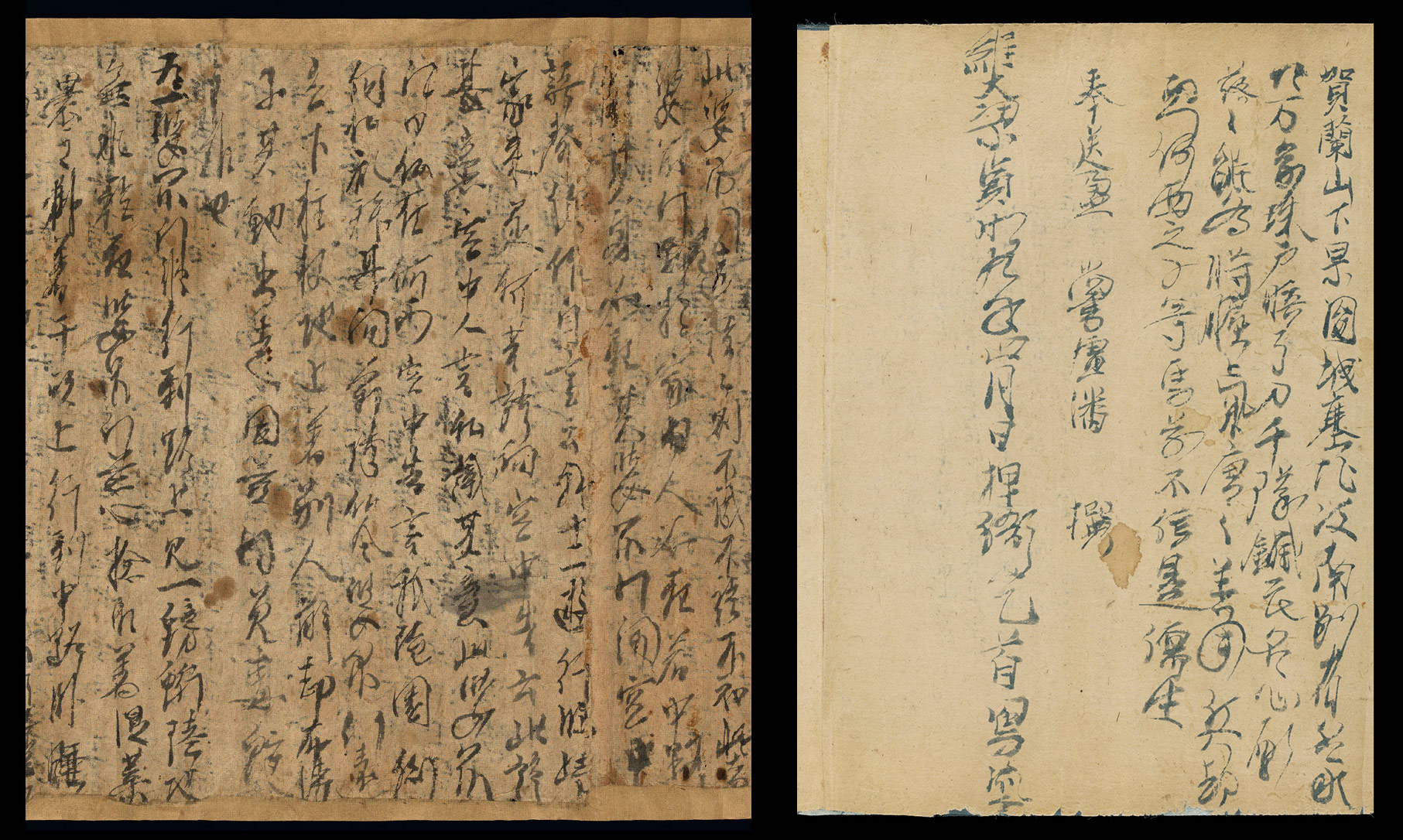

Hao: Their uniqueness and value lie in the fact that they were written by ordinary people, including government clerks, monks in temples, and even school children. In terms of content, Dunhuang manuscripts include government documents, legal papers, tax documents, contracts, and more, all of which are extremely important for understanding the politics and economy of ancient China.

Compared to official histories like the “Twenty-Four Histories,” which only record the political activities of emperors and generals, the Dunhuang manuscripts are mostly original records and archives, not pruned by ancient historians. They preserve many materials that would otherwise have been filtered out by historians, allowing us to understand the social life of ordinary people in ancient times. For example, humorous poems, perhaps written by copyists when they were bored.

Sixth Tone: Have you personally conducted research on the content of these texts?

Hao: I’ve worked on two topics in the past. One was on the social life of Dunhuang monks and nuns from the late Tang dynasty (618-907) to the early Song dynasty (960-1279). The other was a study of sheyi, a kind of grassroots mutual aid organization during the medieval period. Of course, my main focus has been on identifying and transcribing handwritten characters. I believe we Dunhuang scholars have the responsibility to turn texts that people can’t understand into something everyone can comprehend.

Sixth Tone: How about other scholars? Do you see a future in which experts from various fields, not just medievalists, delve into the Dunhuang manuscripts?

Hao: The Dunhuang manuscripts hold significant research value across various disciplines such as history, religion, society, geography, ethnicity, language, literature, art, music, astronomy, calendar systems, mathematics, medicine, and more in ancient China.

Although the IDP committee began pushing for the transformation of Dunhuang studies as early as 2006, even today Dunhuang studies still primarily revolve around history and philology. However, the call for transformation has yielded some results, such as studies in paleography, museology, and knowledge transmission. Overall, the field’s future development requires active exploration of new paradigms and perspectives, as well as the opening up of new research areas. By introducing paradigms from sociology, communication studies, and other fields, we can further enrich the content of Dunhuang studies.

(Header image: Details of the handscroll “Preaching Buddha” from the early Tang dynasty (618-907). From the British Museum)