How China’s Public Institutions Went Crazy for VR

With the development of technology and falling production costs, the speed of digital transformation of cultural intellectual properties is gradually accelerating. This summer, exhibitions and shows featuring virtual reality elements could be seen in multiple venues all across Shanghai.

One such example is “Horizon of Khufu: A Journey in Ancient Egypt” at HKRI Taikoo Hui in Shanghai — a project jointly created by French VR/AR company Excurio and archaeologists on the Giza Project at Harvard University. The show is the first of its kind to survey and scan the interior of the Pyramid of Khufu in Egypt and its surroundings, which have been reproduced in high definition at 1:1 scale using the Unreal engine to create an immersive experience. Visitors simply need to don a backpack and VR glasses to be transported to Egypt and venture inside a pyramid.

“Luoyang VR,” which launched at Tomorrow Square, presents users with a different kind of experience. Based on an entertainment IP, it brings to life a variety of scenarios including night scenes from Shendu, the city tower in Luoyang, and Buddhist fantasy elements. In fact, the whole project is more like a video game. Users first watch an immersive performance before being allocated characters and assigned tasks by NPCs. They then put on VR glasses, transforming them into the character as they are transported back in time to Luoyang where they follow plotlines; interact with the world through such movements as shooting, hiding, climbing, and wading through water; and do battle against a mysterious organization.

In addition to these commercial projects, many public cultural organizations are also exploring VR technology. For example, the Historical Documents Center at the Shanghai Library where I work started putting on digital media exhibitions several years ago, and last year launched its first VR immersive-interactive game project – “Ling Jing Shi Yu.”

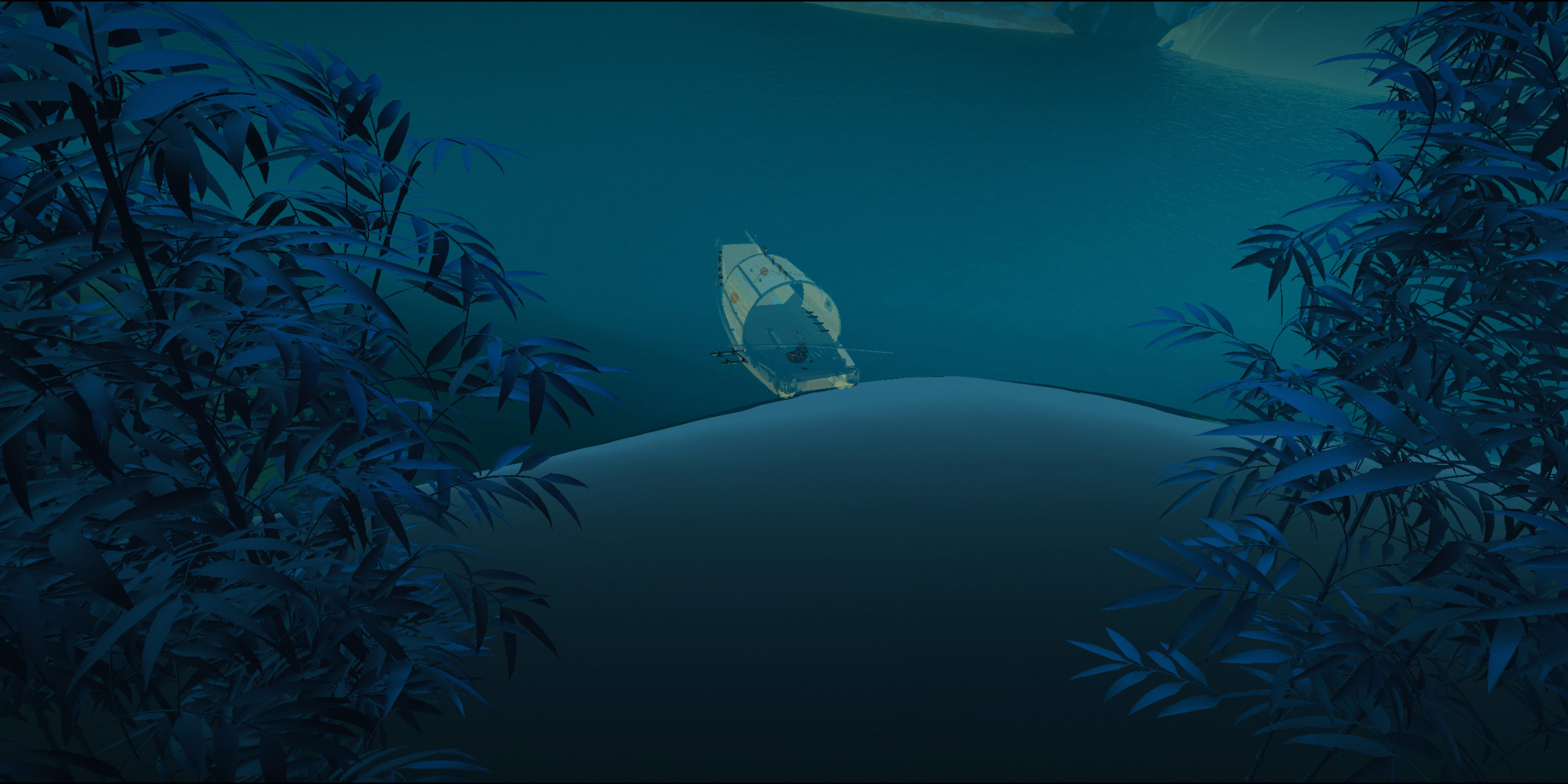

Following on from the success of “Ling Jing Shi Yu,” this summer we launched a new VR immersive-interactive game called “Tracks in the Snow.” The title comes from the name of a poem by the celebrated Song dynasty scholar Su Shi, who wrote: “To what should we compare human life? It should be compared to a wild goose trampling on the snow.”

Unlike “Ling Jing Shi Yu,” which was mostly created based on real scenes or existing works, during the making of “Tracks in the Snow” we extensively referenced AI-generated images. Specifically, we used natural language processing technology to describe each scene with text keywords through an AI system, created a draft with Midjourney, and then used Stable Diffusion and keyword guidance to process the images, so as to obtain more stable and controllable effects. With more than 1,000 images as the foundation, I tried different training methods such as DreamBooth, LoRA and Hypernetworks, and finally trained a proprietary style model. We then imported this into the game engine to form the final result, which has both the detailed brushstrokes of landscape painting, and a new style incorporating high-tech elements such as luminous particles, creating a strong visual impact.

Unlike normal 2D graphic design, VR production is not a process of “what you see is what you get.” In fact, completing the design is only the first step. Repeated debugging and optimization are key to success.

These last two years of experimentation have convinced me of the huge potential for technological innovation in the digital creative industry. In the future, we plan to work with even more new technologies to expand and innovate VR games, and bring audiences new futuristic experiences. However, no matter how much technology there is or how new it is, it must serve the content. The ultimate purpose of immersive games for museums is to shorten the sense of distance between visitors and the artifacts as much as possible. In that way, people can spend time fully engaged in exploring history free from external distractions and be able to personally experience the mysteries and charms of ancient civilizations.

Translator: David Ball; editor: Wu Haiyun.

(Header image: A still from VR immersive-interactive game “Tracks in the Snow.” Courtesy of Shanghai Library)