How Shanghai Is Redefining Aging With In-Home Care

Confined to her bed, Li Mei’s current radius of activity is 1.2 meters.

Just four years ago, she was still traveling the world. “My mother was in good spirits. She even traveled to Japan when she was in her eighties,” said Li’s youngest daughter.

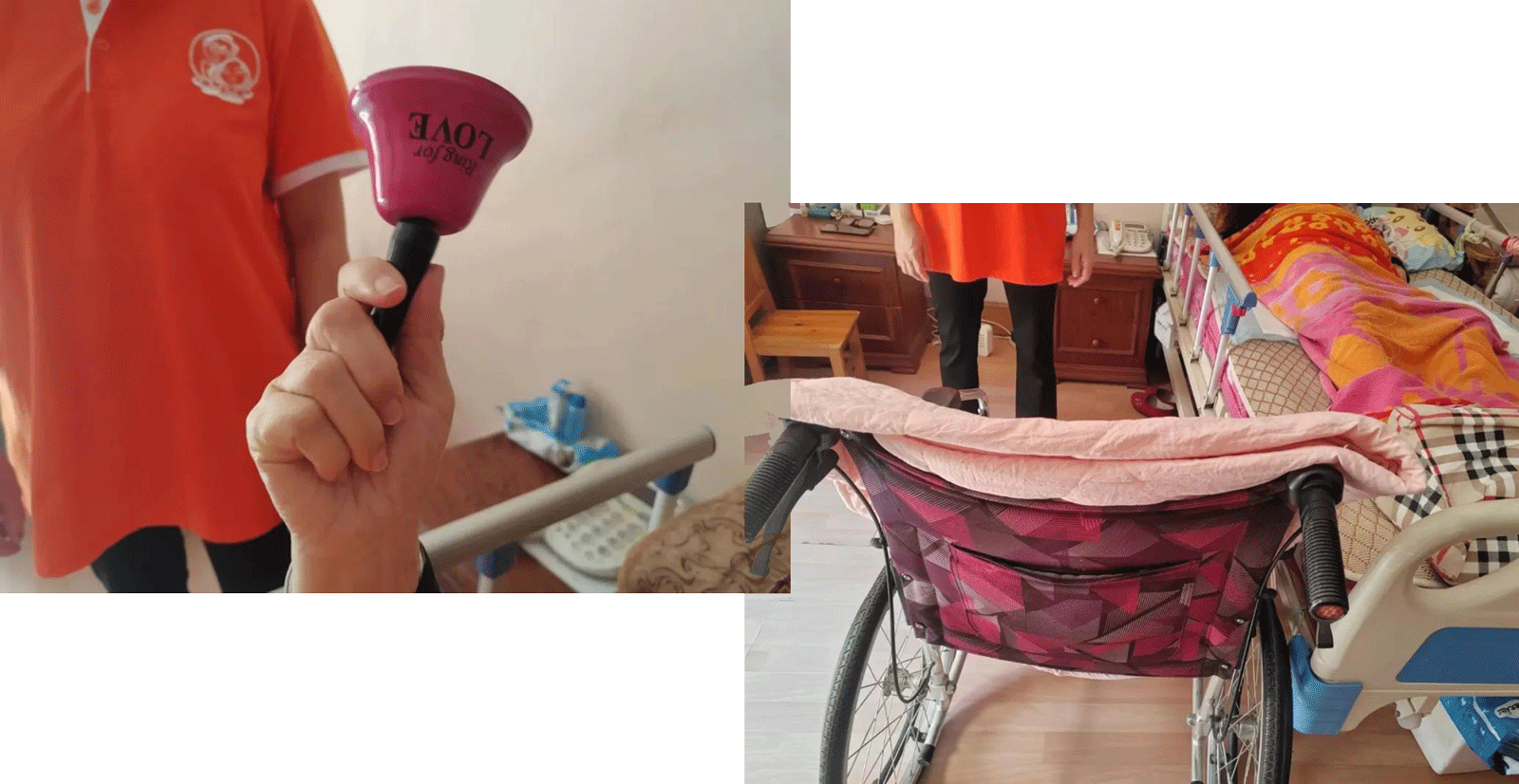

Now 91 years old, Li had a cerebral infarction and has been immobilized on one side of her body for more than three years. Now, in her world, the pink bell at her bedside is her most useful tool. With a shake, Li’s caregiver, Du, who is busy in the kitchen downstairs, will rush up to attend to her needs.

Du was discovered and hired by Li’s eldest son. “My brother likes to ask around. Once, he went to the community center, and people there told him about this service,” said Li’s youngest daughter, referring to the in-house services provided by the government for elderly people with chronic diseases living alone or those requiring assistance with daily personal care.

Longmencun, a neighborhood in downtown Shanghai, has been piloting such services for the elderly since 2019, having served more than 300 elderly people in the area to date, with about 170 currently in service. Across the whole city, more than 3,000 people have benefited from the service as of August.

After Li’s cerebral infarction, her children thought of sending her to a nursing home, but they were reluctant to do so after visiting a few of them. “The nursing homes are all far away, and there are also stipulated visiting hours for family members,” the daughter said. While Li also had a live-in caregiver, challenges arose when the caregiver asked for leave or wanted to resign, particularly during Lunar New Year. When this happens, the in-house services prove reliable: There is always someone to fill in the position.

The distinction also lies in the level of professionalism. In-house services encompass not only domestic work but also massages, medical care, accompaniment for hospital treatment, and the changing of dressings, among others. Du, for example, would assist Li with rehabilitation in morning and afternoon sessions, using equipment to simulate pedaling a bicycle.

Li also requires bathing twice a week, a task beyond the capabilities of her four children. On bathing days, the agency arranging the in-house services sends another worker who is trained for such situations to help. “They’ve all been trained, so they have special skills to lift my mom. This is something that I wouldn’t dare to try. I could fall down with her,” said the daughter, who is 69 herself.

According to the Shanghai Civil Affairs Bureau, in-house services come in different categories. The lowest level, which provides 13 hours of door-to-door services every month, costs 660 yuan ($92) a month, while the most premium one offers a 24-hour escort service for 8,220 yuan a month. Those prices are subsidized by third-party organizations that provide the healthcare service.

To make elderly care more accessible, each residential community has its own policies. Laoximen, a community that administers Longmencun, provides each household with a 300 yuan supplement each month during the first six months of the service.

Able to afford the cost, Li’s family chose the premium service due to Li’s bedridden condition. If the care recipient does not need close monitoring, most families tend to choose a cheaper package, in light of elderly care being a long-term commitment. Notably, most in-house service users are covered by the government’s Long-term Care Insurance (LTCI) pilot program.

Launched in China in 2016 and piloted in Shanghai the same year, the LTCI is a social insurance scheme for the elderly who are unable to care for themselves. The LTCI fund reimburses 90% of the expenses incurred by the door-to-door services, with individuals bearing only 10%. Currently, the average age of LTCI beneficiaries in Shanghai is above 80 years old.

The highest level of LTCI provides seven one-hour service visits per week. The service does not include domestic tasks such as laundry and cooking, and only provides medical and personal hygiene care. These limitations prompt most families to combine LTCI with in-house services.

Liu Genfa and Gu Liqing, an elderly couple, are using such a service package, with Liu opting for a LTCI service of seven hours a week and Gu for three hours a week. Each of them also purchased a separate in-house service of 13 hours per month, costing them 660 yuan each a month.

Since beginning to suffer from Alzheimer’s disease six years ago, Liu has gradually lost the ability to recognize his family. His family calls him “Chief Liu”, the way his former colleagues used to call him when he was working at the Shanghai No.3 Iron and Steel Factory, and now has to coax him into eating and showering. “He was the head of the general services section. He didn’t need to look at the script when making a speech. He was a very eloquent man,” said Liu’s daughter. “But looking at him now, it makes me realize that’s what happens when you get old.”

Liu’s daughter rides a scooter for five minutes to deliver homemade lunches to her father every day and takes him to bed for a nap, while Xie, a caregiver, takes care of him the rest of the day.

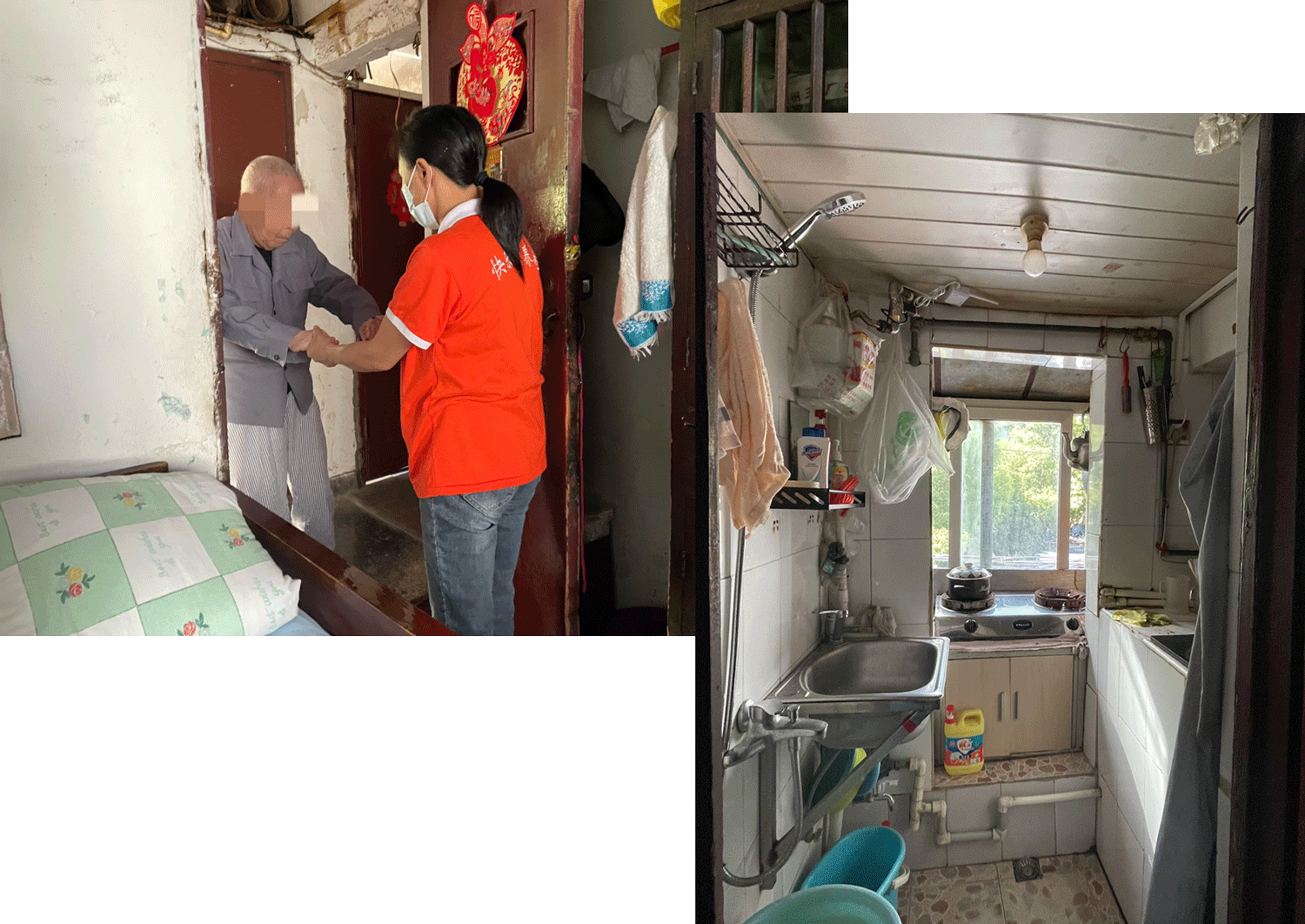

The first task for Xie is to empty the toilet for Liu, as flush toilets have not been installed in the old building that Liu lives in. After that, she cleans the house, does the laundry, and accompanies Liu when doing exercises in the narrow corridor. When in good condition, Liu can do 400 steps walking backwards and forwards. During the process, he counts out loud with Xie, exercising both his body and his brain.

Bathing poses the biggest challenge, as Liu’s bathroom is in a small kitchen with an area of only one square meter. After renovation, a shower was installed on one side of the wall. When bathing Liu, Xie needs to hang the shower curtain on all sides first, and Liu needs to stand up to finish the shower quickly. “Wet him, lather him, and rinse him,” Xie described the process. “He can’t stand for too long. Ten minutes tops. If he falls, it’ll be even more troublesome.”

Li and Liu represent the aging population of Laoximen, where people over 60 years old account for 40.22% of the total registered population. Since 2019, Laoximen has been piloting the in-house service program. A team made up of paramedics, caregivers, housekeepers, and emergency services is assigned to each family.

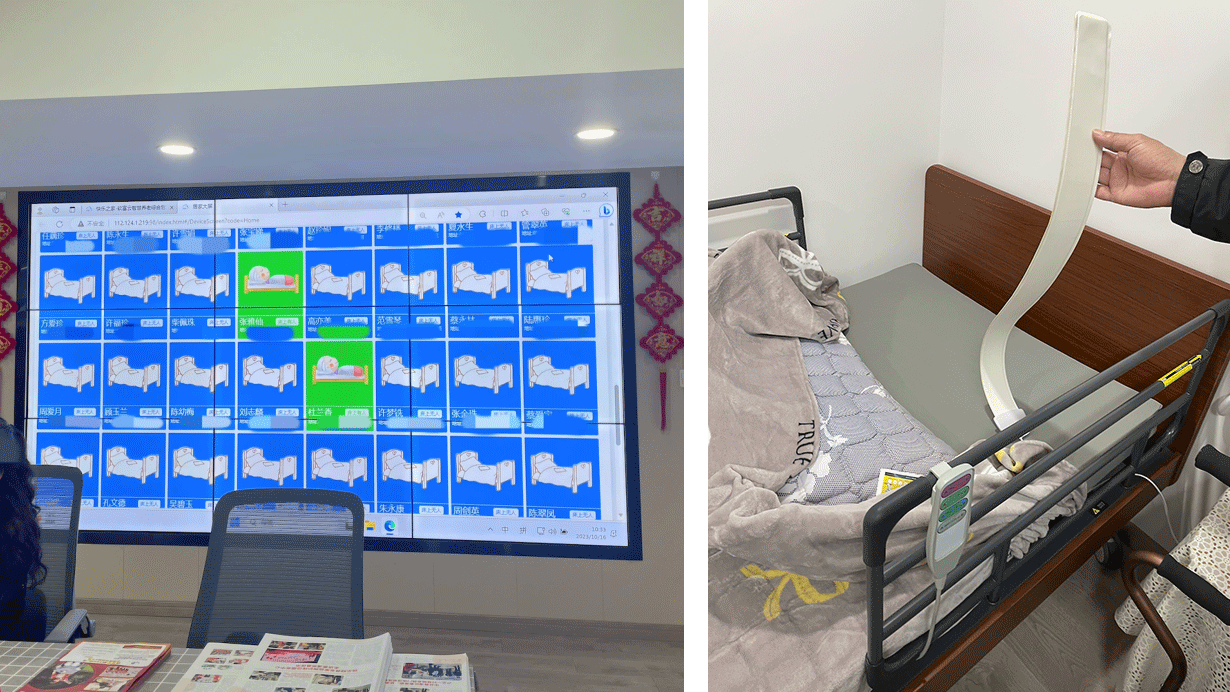

The Laoximen in-house service center, located at 288 Penglai Road, is also Shanghai’s first 24-hour emergency service center. The service center has a large screen that shows the activity of each elderly person. The monitoring band in the bed passes signals to the system: A blue bed means “empty” while a green one means “occupied.” If the bed remains occupied for too long, it will trigger a call to check the situation.

In addition to monitoring bands, emergency call bells are also mandatory and can be installed in areas with active elderly people. Last summer, when a man who lived alone had a heart attack at home and pressed the call bell, the center notified the emergency medical service and sent a helper to the door at the same time. Generally, the center responds within 10 to 15 minutes of the emergency call bell, proving helpful in many critical situations.

Team services like this are provided by third parties, including social groups and private companies. Local authorities offer space and infrastructure, while a third party provides low-profit services. Laoximen’s in-house services are provided by a senior care company that also runs its own nursing home.

“The value of the in-house service is to send professional care to doorsteps, delaying the entry of elderly people into care homes and maximizing time together with family,” said Ding Yong, CEO of izhaohu, a company that utilizes technology to provide care services to the elderly.

Most caregivers employed by companies to provide in-house services are around 50 years old. Du, working 24 hours round the clock for Li, is 56, while Liu’s caregiver Xie is approaching 50. Xie said she used to work at a nursing home, but the workload there was too much for her. “I looked after several elderly people at the same time,” she said. “I couldn’t sleep well at night, worrying if anything may go wrong with any of them.” For her, working as a LTCI caregiver gives her flexibility. “I can at least sleep well at night.”

LTCI caregivers earn a little over 10,000 yuan per month, hard-earned money by any standard. Xie typically works for 10 hours a day, with Liu being her fifth client that day.

According to data from Shanghai authorities, by the end of 2022, LTCI services in the city had provided 2,733,400 visits. That being said, LTCI only provides basic elderly care services, and more efforts are needed to support the elderly’s mental health needs.

“One hour a day or two to three hours a week is far from enough,“ said Tian Jingying, a young worker at the 24-hour emergency service center who is in charge of liaising with about 130 families. Her role involves being the point of communication between the care receivers, their families, and the caregivers. “Every time we visit the elderly, they chat with us for a long time. I feel that they really need to have someone to talk to,” she said.

Xie feels the same way. “Some of the elderly live by themselves, and I’m probably the only person that they see on that day,” she said. “They tell me how happy they are to see me.”

Tian added that children of the elderly people being cared for are mostly 50 to 60 years old, which makes it difficult for them to care for their parents. “They either haven’t retired or need to care for their grandchildren,” she explained.

Shanghai’s elderly population grew by 114,000, or 2.1%, in 2022 from a year earlier, official data in May showed. The number of people aged 60 or above reached 5.54 million by the end of last year, making up 36.8% of permanent residents, up from 36.3% in 2021.

With a larger elderly population than ever today, Shanghai has a long journey ahead to address senior care-related challenges.

Reported by Jiang Tianya and Gu Zheng.

A version of this article originally appeared in SHerLife. It has been translated and edited for brevity and clarity, and is republished here with permission.

Translator: Eunice Ouyang; editors: Xue Ni and Elise Mak.

(Header image: Er Hei/SHerLife)