For Chinese Rock Bands, a Shortcut to Fame Comes With Questions of Integrity

When indie rock band Huxiaochun launched their first nationwide tour in 2019, the band’s four members had to take out loans of 2,000 yuan ($283) each just to afford to rent equipment and pay for the venues. The band was disheartened when only 60 people showed up to one of their dates in Shanghai.

Four years later, the band from the northwest Gansu province now appears at major music festivals almost every weekend, where they are watched by thousands.

The band is one of many that are riding a wave of demand for rock music in the past year. At least 40 music festivals were held across the country during the weeklong National Day holiday in October, nearly four times more than in the same period in 2022 and double that of 2020.

The band’s transformation from obscurity to mainstream recognition is down to their choice to participate earlier this year in one of China’s biggest music competition television shows, “The Big Band.”

First aired in 2019, each season features around 30 bands who go up against each other with live performances of their best songs, covers, and even last-minute compositions, which are then judged by a studio audience, music critics, and a handful of celebrities.

The show was a hit as soon as it launched, hitting a peak of 170 million views in 2020. Though the latest season, which began in August, saw the lowest viewing figures of the show’s three seasons, cumulative views still reached 130 million in around 50 days, according to Yunhe Data.

The bands that choose to appear on the show are now often top of the bill at the country’s many music festivals. Some are selling out large-scale arenas for the first time, while others are embarking on world tours.

But the mainstreaming of what was for many years the niche interest of a small but passionate group of fans is also worrying industry veterans and some musicians themselves. As demand for their music soars, and opportunities to make money increase, they are having to confront the age-old question of how to maintain their integrity in the pursuit of fame and success — all the while wondering whether such opportunities will come again.

Rock, for sale

“The Big Band changes bands like us the most,” says Liu Yusi, guitarist for Sisi & Fan, a female duo from the central Hunan province who participated in the show’s first season. Like Huxiaochun, Sisi & Fan was practically unknown before they were selected to be on the show.

Formed in Beijing while vocalist Zhou Fan was still at university, both band members were holding down multiple jobs to get by in the early years, including graphic design, production assistant, and video production. Some of their early shows were only attended by a handful of people. But after one of Zhou’s classmates who worked at the show’s production company recommended them for the show, they finally got the break they were waiting for.

Though they didn’t get past the show’s first round, their performances were enough to amass them a national following enchanted by their childlike vocals and throwback guitar sounds. They began appearing in music festivals and earning a full income from music for the first time, even appearing on “National Treasure: Performance Season,” one of China’s biggest cultural variety shows broadcast on state broadcaster CCTV, exposing them to tens of millions of viewers.

The sudden elevation of obscure bands like Sisi & Fan was what caught the eyes of members of Second Hand Rose, the legendary experimental folk-metal band from Northeast China. The band had rejected multiple invitations to participate in the first two seasons of the show; they were already a big name in the Chinese music scene, having been the first domestic rock band to perform at the Beijing Workers’ Stadium in 2013.

But the band began to feel the show’s impact on the industry after the first two seasons. In an interview with domestic media outlet Positive Connections, lead singer Liang Long said “The Big Band” was the first show he had seen that truly made rock music mainstream in China.

“To be frank, if you went to the mall and suddenly saw a brand advertisement featuring another band, you’d be lying if you said you weren’t jealous. We are in the same industry; how did they suddenly appear on a billboard?” he told the outlet.

After the start of “The Big Band,” Liang said many unfamiliar bands began performing alongside them at music festivals, with some even replacing Second Hand Rose as headline acts. Insiders have joked that certain music festivals are now “The Big Band music festivals” because most of the bands performing are from the show: “The entire market structure has changed,” added Liang.

According to a 2022 poll of 362 music fans and industry professionals, 58.8% believe that major variety shows are now the most significant factor in “creating stars and rapidly gaining popularity.” Additionally, 40.3% of respondents say that these shows are shrinking the market for bands that do not participate in them.

Irreversible, an indie rock band from Changchun in the northern Jilin province, has felt firsthand the impact of “The Big Band” on the industry. The band had achieved national fame in the mid-2010s and even appeared in another music variety show “China’s Top Band” in 2017.

The band split up in 2018 just before “The Big Band” first aired due to discontent between its members. When the band tried to get back together last year, what they found was a market dominated by “internet celebrity” bands, particularly those that have appeared on “The Big Band.”

“The short-term impact (of the show) is that people only listen to the top bands promoted by it,” says bassist Wanyan Chunxi. “Now almost every (promotion) requires the internet … the times and the audience have changed.”

The changing of the times is integral to the music of Huxiaochun. “We live in a period of rapid development, so fast that we’ve become numb,” reads the band’s bio on music streaming platform NetEase.

The band’s music expresses feelings of hopelessness in the midst of societal changes around them, expressed in extended instrumental sections in their songs and lead singer Ping San’s schizophrenic vocals that alternate between spoken word and screaming.

Though Huxiaochun only managed to make it to the first round of the show, they still attracted many new fans and even went viral with their interactions with the celebrity judges. Their style has proved a hit with listeners looking for music to help them release stress and negative emotions.

However, the increasing “functionality” of their music does not sit well with the band members. Along with their newfound popularity, they’ve found it more difficult to make the music they want to make: songs with deep meaning, not just songs that make people feel good.

“Our fanbase now just wants music from us that is very direct and simple, that directly hits them in the face and makes them feel good, because I feel many of them are not very happy nowadays,” says Ping.

The flipside of fame has been difficult to contend with especially because it has always been a goal for the band. At the very least, it would help justify their career decisions in the eyes of their family members, in a society that still does not deem music, especially rock music, a respectable career path.

“I don’t actually think there are more people listening to rock music,” says Ping. “It’s just that more people are jumping on the bandwagon … and doing what is fashionable.”

Some have blamed the “The Big Band” for promoting a style of rock that caters to mainstream sensibilities. Not only was Huxiaochun eliminated in the first round of the latest season, but other more experimental bands also left the competition in the early stages, including Beijing noise rockers Birdstriking and Hangzhou math rock outfit GriffO.

Criticisms of the show diluting the genre intensified during the latest season after voting was equalized, giving the studio audience, music critics, and celebrities one vote each, rather than giving critics and celebrities more voting power as was the case in previous seasons. This meant that each band’s fate was now largely decided by members of the public in the studio audience due to their numerical advantage.

This increasing convergence of Chinese rock music and the public’s tastes is not necessarily positive, says Fei Qiang, a veteran Shanghai promoter who opened the city’s first “livehouse,” Ark, more than two decades ago. He distinguishes between “rock culture,” which emphasizes independence, and “rock band culture,” which is what has now become mainstream in China.

“Many bands are becoming more and more commercial and entertainment-oriented, which is conducive to being accepted by larger audiences. This is understandable because music is not only for oneself to enjoy but also for the public to enjoy. But their musical exploration and expression are becoming much weaker because they focus more on entertainment and trends, so that more people can accept it,” says Fei.

Catch-22

Defenders of “The Big Band” say that the show does not merely champion “safe” bands, citing the winners of the show’s three seasons as evidence: New Pants, pioneers of China’s new wave indie scene; Re-TROS, an underground post-punk group that sings only in English; and Second Hand Rose, which has often courted controversy for their flamboyant stage antics through the years, including lead singer Liang’s cross-dressing during live shows.

The show’s ability to elevate the profiles of these hugely respected underground bands has won it praise among musicians and critics. It is also why many are calling for the show to return, amid rumors that the third season of “The Big Band” was also its last.

On the other hand, several bands have also declined invitations to appear on the show, and the increased fame and money that would surely come along with it. These include Shijiazhuang progressive rockers Omnipotent Youth Society, and Chengdu indie rock bands Hiperson and Stolen.

According to Wang Shuo, a music critic on the show, the reason is that these bands’ credibility among fans would be undermined by their appearance. Omnipotent Youth Society, in particular, is known for their music’s frank depictions of modern life, captured in realist tracks like “Kill That Shijiazhuang Man.”

Among the 42 music festivals held during the Labor Day holiday this year, Second Hand Rose and Omnipotent Youth Society were the two most invited bands, with five and four sets respectively. With one now achieving new levels of fame, and the other shirking the opportunity entirely, it remains to be seen how the two bands fare in the coming years — and especially whether their music takes on different paths.

Meanwhile, smaller bands continue to ply their trade. For Gou Hongzhao, lead singer for Beijing indie band Residence A, the day-to-day impact of the show has been the increased cost of booking venues and recording sessions, as competition has soared.

Like them, indie band Unforeseen from Xi’an, northwest Shaanxi province, is also struggling to make ends meet, almost two decades after forming. All four members of the band are still only able to afford to play music part-time.

“I don’t look forward to the future,” says bassist Wang Zhe. “Rock music should be about independent thinking, but how many people are doing it these days?”

The band’s name comes from the uncertainty the members felt when they first formed the band — an uncertainty that has returned in recent years. As they read and hear about the explosion of rock music in China, they are left wondering what audiences really want these days, and also what the market wants. Their future, and the future of Chinese rock music, remains to be seen.

Editor: Vincent Chow.

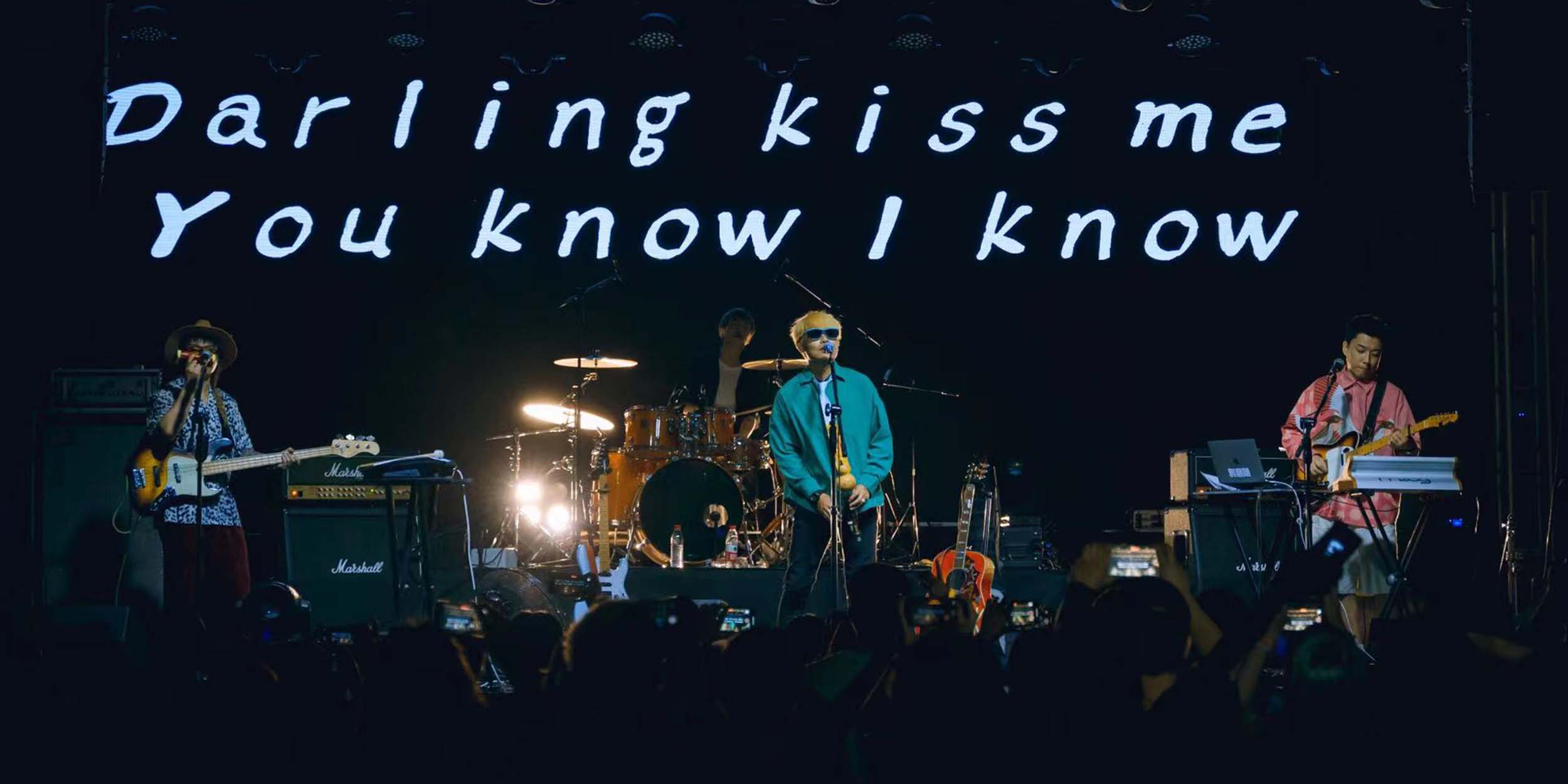

(Header image: Irreversible performs at a livehouse. Courtesy of Irreversible)