Changing Course: Why More Chinese Students Are Eyeing Southeast Asia

About a year after graduating with a degree in marketing in 2021, Zhang Xin stared at two daunting options: either continue her high-stress job as an event planner or brace for the fierce competition of China’s postgraduate exams.

Tired of the rat race and desperately looking for a fresh start, Zhang, who also worked as a bartender to earn extra income, chose a third, more radical option. She quit her job and set her sights on Thailand, where she applied for a postgraduate degree in business management.

“I decided in early 2022, after spending months sitting at home under pandemic restrictions. It was my one chance,” 26-year-old Zhang tells Sixth Tone from Bangkok. “Moreover, I’ve always been fascinated by Thailand, and I really wanted to see what life is like there.”

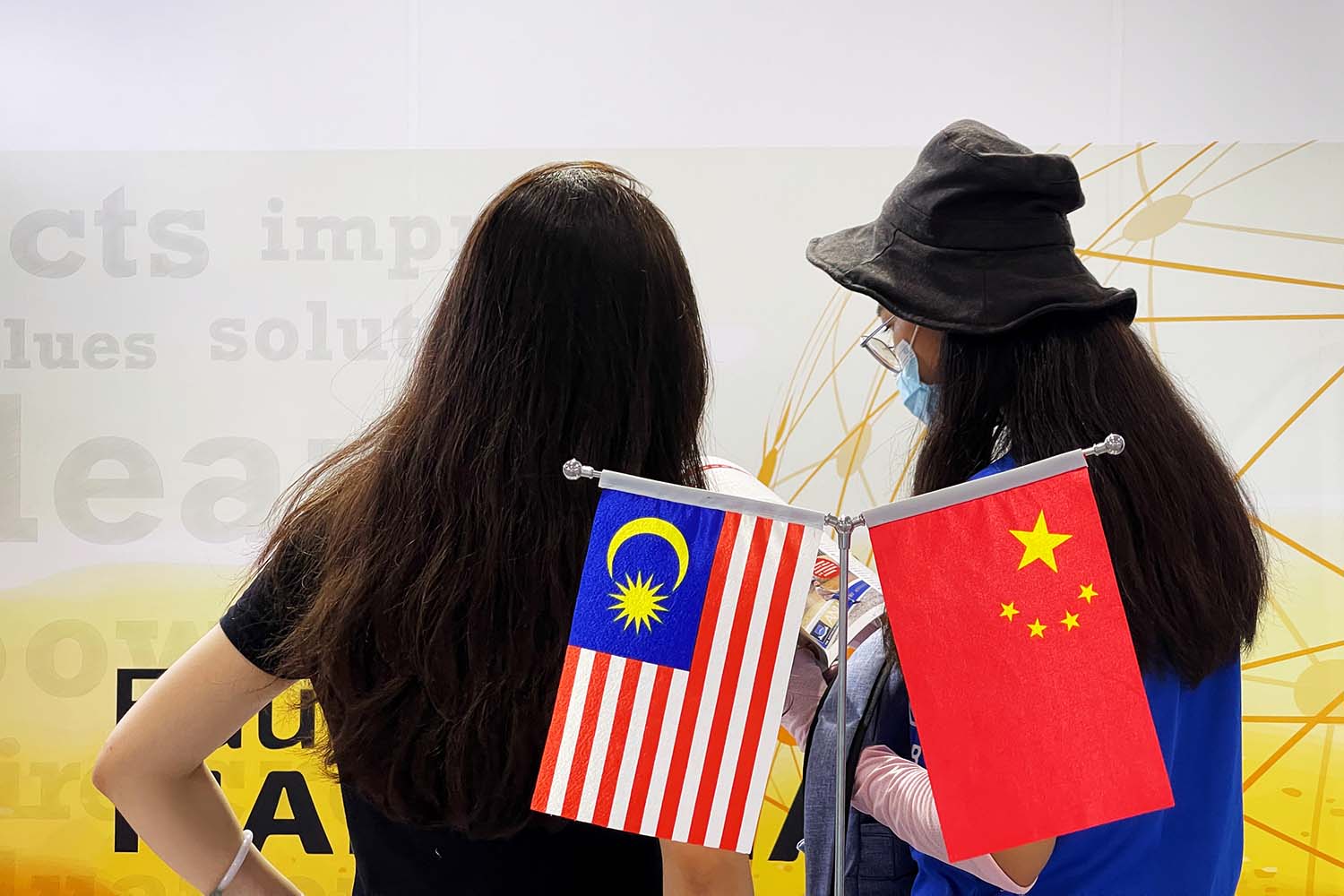

Zhang’s choices mirror a wider trend taking root across China, where an increasing number of students are turning their gaze towards Southeast Asia, particularly Malaysia, Thailand, and Singapore.

For instance, in Thailand, Chinese students comprised the majority of international students in 2022, with 21,419 enrollments, a 130% increase from 9,329 in 2012. Popular fields of study include business administration, law, the arts, humanities, and education.

Similarly, China emerged as the top sender of international students to Malaysia and Singapore. In the second quarter of 2023 alone, Malaysia saw an influx of students from China, with 4,700 new applications, marking an 18% increase from the previous year. And as of June 2023, Singapore was home to approximately 73,200 international students, with Chinese students making up about half.

While countries such as the U.S., the U.K., and Canada remain the most popular choices for Chinese students seeking overseas education, increased visa restrictions, escalating geopolitical tensions, and higher costs of education and living are pushing many to reconsider.

Students and education experts also tell Sixth Tone that the rise in anti-Asian sentiment has prompted many in China to seek alternatives in Southeast Asia due to affordability, relaxed visa policies, and cultural familiarity.

Cost and effect

When Zhang began applying to postgraduate courses in Thailand in February 2022, all she needed was her undergraduate degree, transcripts, and basic English skills.

“My English wasn’t that good. However, they only required basic communication skills along with a simple speaking test — that’s it,” says Zhang.

Given her limited English, Zhang chose not to prioritize school rankings during her application process. Instead, she picked three universities based on her personal preferences. Four months later, she received and accepted an offer from Rattana Bundit University, a private university in Bangkok.

In stark contrast, pursuing postgraduate education in China presents a far more arduous path. The data tells the story: The number of registrants for the national entrance examination for postgraduate programs in China surged from 1.51 million in 2011 to 4.74 million in 2023.

And according to official data, only an estimated three out of 10 aspirants made it through between 2014 and 2023.

“I feel that pursuing postgraduate studies in China is relatively challenging,” says Zhang. “In Thailand, the duration for a master’s degree program is comparatively shorter too.”

In addition to the relatively stress-free application process, the affordability of tuition in countries like Thailand add to their appeal.

According to Zhang, her two-year postgraduate program there would cost her around 150,000 yuan ($21,014), which is nearly equivalent to the tuition fees for one year of study in the U.S.

The annual tuition for postgraduate programs in the U.S. typically ranges from 200,000 to 350,000 yuan, while in the U.K., it costs between 100,000 to 300,000 yuan each year, according to a report on China’s study-abroad market in 2023 by EIC Education.

“My purpose is just to get a degree, go explore a country I like, and develop my English skills a little bit. In Thailand, language education is more cost-effective for me,” says Zhang.

She adds that she’s among the youngest students in her class and that most of her classmates are middle-aged individuals pursuing a master’s degree to meet job requirements in their home countries.

Chang Le, another Chinese student, chose to move to Malaysia after completing the gaokao, China’s college entrance exam, in 2022. “I just wanted to go out and experience the outside world while I’m young,” says Chang, a first-year psychology student at the National University of Malaysia.

In 2022 alone, over 38,000 Chinese students were enrolled in tertiary education in Malaysia, nearly double the 20,000 in June 2021, with many opting for programs in social science, business, and law.

For students like Chang, who grew up in an ordinary family, Malaysia is also an affordable alternative. She says her three-year undergraduate program will cost her family just over 100,000 yuan.

“Ordinary families like ours cannot afford Western education. If I was to study in Britain or the U.S. for three years, to be honest, it would be very difficult, and I wouldn’t want to do that either.”

‘Watery’ degrees

According to Joshua Mok Ka-ho, vice-president of Lingnan University in Hong Kong, the increasing scrutiny over student visas in Western countries is a growing concern for Chinese students and their parents.

“This doesn’t bode well for students from China or Asia studying abroad. Because politicizing higher education internationally will create unnecessary perceptions of anxiety, which perhaps still remain among students,” says Ka-ho, who researched Chinese students’ overseas education choices during the COVID-19 pandemic.

While there’s been a gradual recovery in the demand for overseas education following the easing of travel restrictions since December 2022, the number of Chinese students in the U.S. has slightly decreased.

According to Open Doors data, the count dropped by 0.2%, from 290,086 in the 2021-2022 academic year to 289,526 in 2022-2023. Despite both governments recognizing the value of student exchanges, incidents involving the intense scrutiny of Chinese students at U.S. entry points and visa cancellations have raised concerns among domestic authorities.

Ka-ho underscores that overseas education is seen as an investment by Chinese families, and international news reports of Western countries taking a tougher stance on Chinese students are perceived as potential risks in selecting a study destination.

“Chinese students are very clever when there are choices. They may be calculating all the choices and managing the risk,” Ka-ho said. He also noted that China’s growing ties with ASEAN countries through projects like the Belt and Road Initiative make these nations a “safer” choice.

Chu Zhaohui, a researcher at the China National Academy of Educational Sciences, agrees that the growing popularity of higher education in Southeast Asian countries is primarily driven by lower tuition costs.

“Changes in the international environment will impact how people choose destinations for overseas education, but the impact will mainly be seen on the high end (those who can afford higher education in Western countries), not the low end,” says Chu.

He added that despite a slight decrease in the number of Chinese students in the U.S. in 2023, the country is likely to remain a top choice for many due to its high-quality education.

Zero Lin, a second-year postgraduate student at the National University of Singapore, transitioned his studies from the United States in 2022. His choice was driven by a desire to specialize in international relations in the Asia-Pacific region and concerns over the rise in anti-Asian sentiment during the pandemic.

“The atmosphere (in the U.S.), especially during the pandemic, made it difficult for me, and the distance from home was a concern,” he explains.

In Singapore, Lin found not only more affordable tuition but also a more welcoming social environment. “Singapore’s majority Chinese population and cultural acceptance create a sense of belonging,” he says.

Despite increasing interest in higher education closer to China, degrees from some Southeast Asian countries are often underestimated due to their lower entry requirements.

On Chinese social media, for instance, some refer to the education experience in these countries as shui shuo or shui bo, which translates to “watery master’s” or “watery doctorate degrees” in English, implying that these degrees are perceived as holding less value than those from Western countries.

Despite such perceptions, students say they place more value on their overseas learning experience than the school’s reputation. “No matter which country you go to, it’s still an opportunity to experience the outside world,” says Chang.

With only three months left before her program finishes in March, Zhang is busy preparing for her thesis defense. Despite her future plans remaining uncertain, she says she’s still optimistic.

“Though Thailand isn’t seen as a mainstream country with significant competitive advantages, there are still opportunities here,” she says. “Studying in Southeast Asia is a valuable experience in itself, even if it doesn’t lead to a high-paying job.”

Editor: Apurva.

(Header image: VCG)