AI Is Taking Off in China. So Are Worries About Its Future.

What a difference a year makes. In the 13 months since OpenAI launched ChatGPT, its groundbreaking chatbot, the world has seen an explosion of new AI applications, from simple image generators to advanced multimodal systems that can process all sorts of inputs including text, images, and speech.

While much of the conversation about AI’s potential has focused on issues caused by the misuse of these applications, including misinformation, privacy violations, and plagiarism, industry leaders such as OpenAI’s Sam Altman are already warning about the existential risk to humanity posed by even more advanced AI.

Their concern is that it will be difficult to control AI systems if they become more intelligent than humans — a benchmark known as artificial general intelligence.

The challenge of ensuring human control over AGI has made AI safety a mainstream topic, most notably at the AI Safety Summit held in the United Kingdom last November. As one of the world’s leaders in AI development, China’s perspectives on these issues are of huge importance, yet they remain poorly understood due to a belief outside China that the country is uninterested in AI ethics and risks.

In fact, leading Chinese experts and AI bodies have not only been active in promoting AI safety internationally, including by signing on to the safety-focused Bletchley Declaration at the UK summit, but they have also taken concrete steps to address AI risks domestically.

“There has been substantial progress in the past few years with regards to safety risks associated with more powerful AI systems (in China),” says Jeff Ding, an assistant professor of political science at George Washington University and creator of the ChinAI newsletter.

“This momentum is coming not necessarily just from policy actions but also from labs and researchers that are starting to work on these topics, especially at leading institutions such as Peking University and Tsinghua University.”

Major moves

While Chinese policymakers have introduced numerous regulations for recommendation algorithms and “deepfakes” — fake videos or recordings of people manipulated through AI — there has been a clear rise in interest in AI safety over the past year, according to a recently released report from Concordia AI, a Beijing-based social enterprise focused on AI safety issues.

For example, municipal governments in major tech centers like Beijing, Shanghai, Guangdong, and Chengdu have introduced specific measures promoting AGI and large model development. Importantly, some of these measures also call for research into aligning AGI with human intentions, while the Beijing municipal government has called for the development of benchmarks and assessments to evaluate the safety of AI systems.

Given Beijing’s importance in China’s AI ecosystem — the city is home to almost half of China’s large language models, or LLMs, and also far ahead of any other city in terms of AI researchers and papers published — the capital city’s measures are particularly noteworthy and may be a precursor to future national policies, Concordia AI wrote in its report.

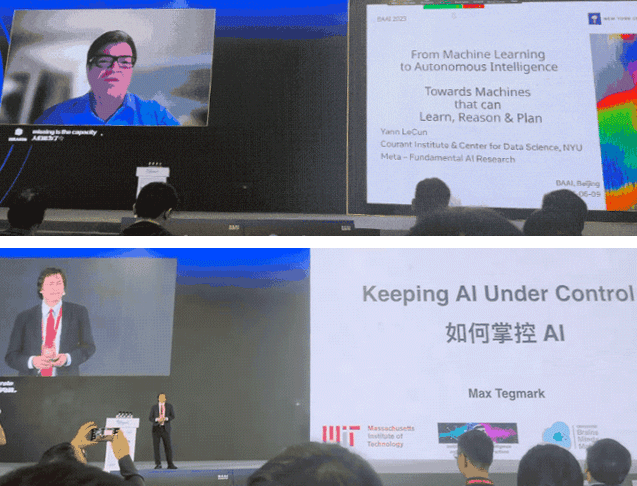

Concern about AI safety extends into industry circles. Last year’s Beijing Academy of Artificial Intelligence Conference, one of China’s leading AI gatherings, was the first to have a full day of speeches dedicated to discussing the risks associated with AGI. (OpenAI CEO Sam Altman used his timeslot to call for global cooperation with China to reduce AI risks.)

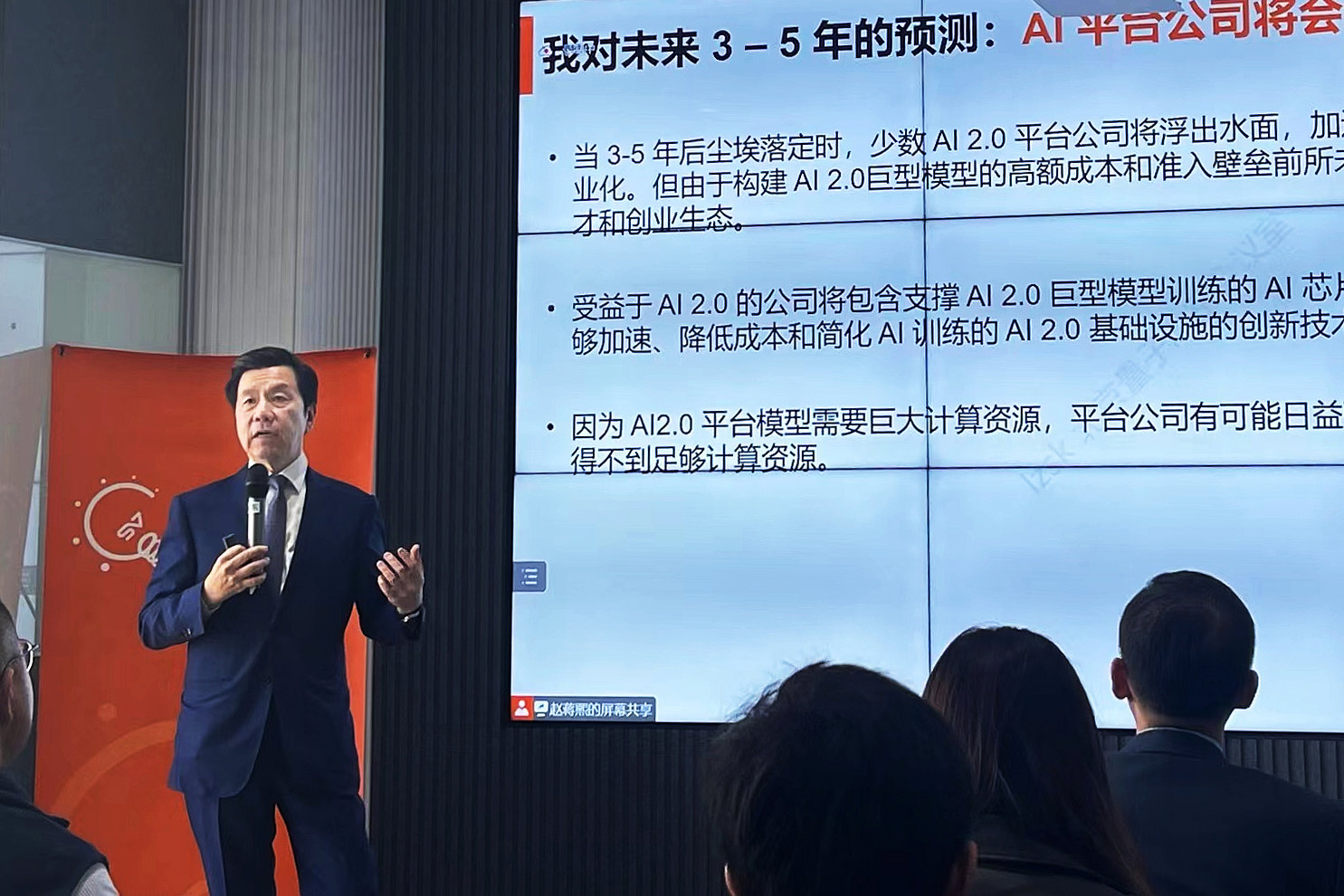

A clear example of Chinese industry leaders beginning to take AI safety seriously is Lee Kai-Fu, the former Google China president and one of the leading voices on AI in China.

Lee, who launched an AI startup in July, had previously focused on societal issues caused by AI, such as deepfakes and bias. But in late November, he and Zhang Ya-Qin, a former Baidu executive and current director of the Tsinghua Institute for AI Industry Research, called for a minimum percentage of AI resources to be devoted to addressing safety issues. Lee proposed at least one-fifth of researchers, while Zhang called for 10% of capital.

Also in November, a group of Chinese academics, including Turing Award-winner Andrew Yao and Xue Lan, director of the Institute for AI International Governance at Tsinghua University, signed on to a global call for a third of AI research and development funding to be directed toward safety issues.

“It appears that there is already a level of agreement between the Chinese and international scientific communities on the importance of addressing AGI risks,” says Kwan Yee Ng, senior program manager at Concordia AI.

“Probably the most important next step is concrete action to mitigate risks.”

Room for improvement

Yet funding for safety research is a weak spot. According to Concordia AI, China has yet to make a major state investment in safety research, whether in the form of National Natural Science Foundation grants or government plans and pilots. It remains to be seen whether a new grant program for generative AI safety and evaluation announced last December signals a shift in this approach.

Meanwhile, AI safety research in China is mainly focused on models we see around us today rather than on the more advanced AI models expected in the coming years.

This focus on present issues is similar to the situation in the United States and Europe, where issues like discrimination, privacy, and AI’s impact on employment have dominated much of the discussion surrounding AI risks.

Fu Jie, a visiting scholar at the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology, is one of a small number of researchers studying AI safety in China. Specifically, he is trying to find ways to improve the “interpretability” of advanced AI systems, allowing humans to better understand the internal decision-making of AI models.

However, he estimates less than 30% of his time is actually spent on safety research, in part because he has not been able to secure adequate funding, especially from industry sources.

“For many researchers, doing safety research so far has mainly relied on self-motivation or voluntary investment of their time and effort,” he says.

According to Fu, awareness of AI safety has increased “noticeably” among Chinese AI researchers over the past year. What is needed now, he believes, are the right incentives for them to pursue this research, such as opportunities for career advancement and funding.

“People naturally need to know that doing this research won’t hold their careers back,” Fu says. “What I’m doing now doesn’t necessarily guarantee a reward career-wise.”

There is also the issue of how “safety” is interpreted. In Chinese, the word anquan is used to describe both AI safety and AI security. While the former is about human control over AI, the latter refers to issues such as content security and cybersecurity of AI systems — stopping bad actors from hacking into AI systems, for instance.

It is sometimes unclear which of the two is being referred to when the term appears in policy documents and industry papers, says Ding. But he also believes safety and security research can be complementary, citing as an example the algorithm registry introduced in March 2022, which he thinks could be used to regulate AGI in the future.

“I think it’s important to be precise about the context in which the term anquan is used … but (AI security) can also be used as a building block to address the risks of more advanced AI systems as well,” he says.

Fu also believes some of these issues will be resolved with time. “Researchers may increasingly feel that these models are a tangible kind of threat as they become more intelligent,” he says. (According to SuperCLUE, a leading Chinese LLM evaluator, China’s top models, including Baidu’s Ernie Bot and Alibaba’s Tongyi Qianwen, have already surpassed GPT-3.5.)

There are signs that this shift is already underway. In October, China’s Artificial Intelligence Industry Alliance (AIIA) — a major state-backed AI industry association —announced new AI safety initiatives, including a “deep alignment” project to align AI with human values.

A national AI law is also in the works, with early expert drafts containing provisions aimed at preventing loss of human control over AI systems.

An international dialogue

As AI models become more powerful, international cooperation is even more important. With China and the U.S. launching a landmark intergovernmental dialogue on AI at November’s APEC Summit, there is a “great window of opportunity” for communication between leading Chinese and American AI developers and AI safety experts, says Concordia AI’s Ng.

“These dialogues could discuss and strive for agreement on more technical issues, such as watermarking standards for generative AI, or encourage mutual learning on best practices, such as third-party red-teaming and auditing of large models,” Ng says, the former referring to the simulation of real-world cybersecurity attacks to identify system vulnerabilities.

Ding agrees that communication between industry actors is key — but it may not come easy. In a market that is expected to be worth up to $2 trillion by 2030, the incentives for sharing information with potential competitors are weak.

“There are a lot of additional complications as people in industry circles might be worried that, when they discuss AI safety issues, they’re revealing something related to their own company’s AI capabilities as well,” says Ding.

Nonetheless, leading AI developers have shown that they are not opposed to working together on AI safety. The AIIA launched a working group focused on AI ethics in late December, while leading U.S. developers such as OpenAI and Anthropic launched an industry body to coordinate safety efforts in July.

The effectiveness of industry-led initiatives remains to be seen — especially as the recent OpenAI governance debacle raises questions about the ability of powerful companies to govern themselves, says Concordia AI’s Ng. On the other hand, greater government involvement in China’s AI ecosystem might also make coordination between various key actors easier to achieve.

For researcher Fu, increased academic collaboration might be a more realistic first step. He has seen more opportunities for cooperation with foreign scholars in the past year as attention to AI safety has increased around the world.

“The real challenge is the fact that even though everyone’s awareness has increased, we still don’t know how to solve these safety problems,” he says.

“But we still have to try.”

(Header image: Visuals from nPine and ulimi/VCG, reedited by Sixth Tone)