China’s Vet Shortage, by the Numbers

Yang Fangyi never intended to sell clothes. A lifelong lover of animals, she dreamed of one day becoming a veterinarian. But after completing a four-year degree in veterinary science in 2018, she found herself staring down years of low pay and long hours.

“If you’ve just graduated or are an intern, the salary is very low,” she says. “It gets to the point that you’re basically paying to go to work.”

She eventually cracked under the pressure of constant 12-hour shifts. In 2019, she quit the veterinary industry and began selling women’s clothes online: “It’s easy work, and the barriers to entry are low.”

Yang is far from alone. China produces more than 10,000 veterinary science undergraduates every year, but poor pay and a brutally competitive advancement track mean that fewer than 10% will stay in the field, according to an industry consulting group. The vast majority, like Yang, opt to change careers, or else take their chances on the civil service or postgraduate exams.

The result is a dire shortage of vets. Despite a booming pet industry, China has less than one-third the number of vets per capita as the United States or European Union.

That shortfall is likely to grow as pet ownership rises and the country’s farms transition to more industrialized agricultural practices. Yet pay for veterinarians remains below the national average, especially for fresh graduates, squeezing the industry and driving young vets away.

Vets for pets?

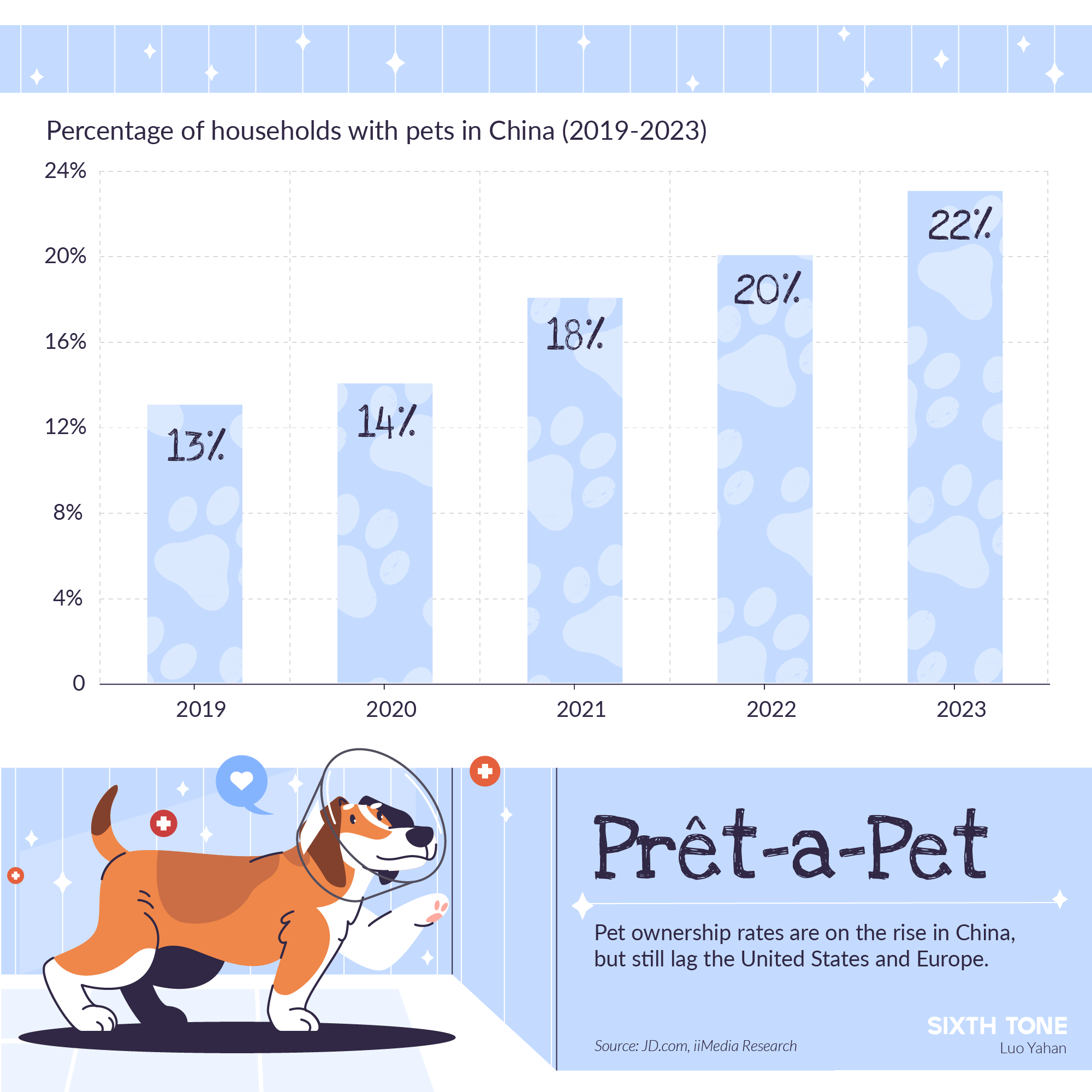

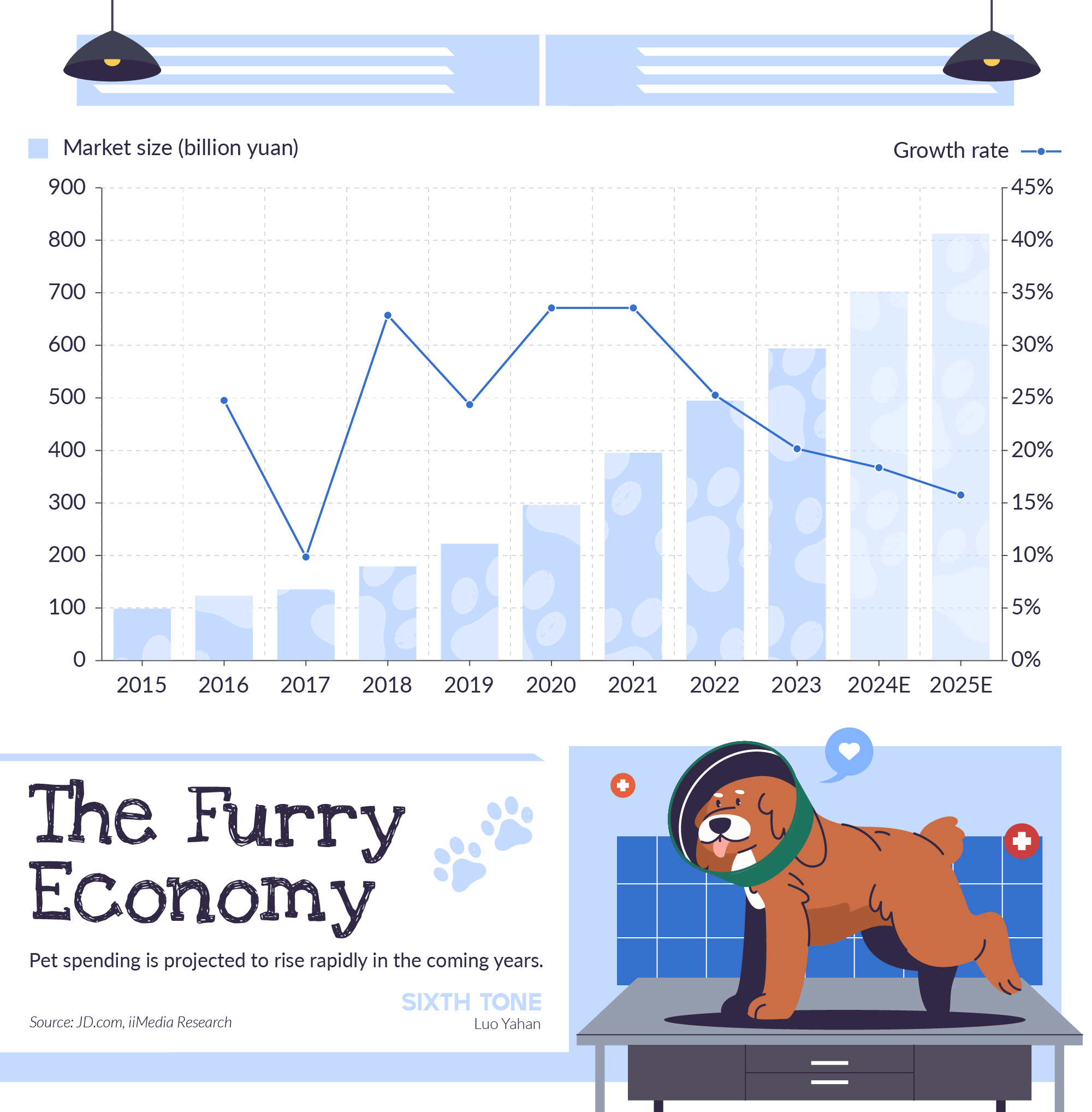

The past decade has seen meteoric growth in China’s pet-centered “furry economy.” One recent survey estimated that Chinese households were raising 51.75 million dogs and 69.8 million cats in 2023.

Market intelligence firm iiMedia Research likewise found that more than one-fifth of households had at least one pet. That may already sound like a lot, but there is plenty of room for growth: China still lags behind the United States and Europe, where 70% and 46% of households keep pets, respectively.

Many prospective veterinary science students imagine they will spend their careers tending to this booming market, but most university programs remain geared toward agriculture rather than pet care.

Only a handful of schools offer students the choice to specialize in what’s known as small animal medicine. At China Agricultural University, which has the country’s top-ranked veterinary science program, the courses devoted to small animals are all electives, and there is no dedicated small animal veterinary science track.

A broad base of knowledge is critical to students’ future success, but for those attracted to the major by their love of pets, this focus on husbandry and livestock can come as a shock.

This is especially true for those who perform their required internships on large farms, like Chen Jiaxi, a fifth-year student at South China Agricultural University — one of the few schools in China that offers a major in small animal medicine. Chen plans to switch to a resource track after graduation, rather than work on a farm. “(Working at) an animal hospital would be acceptable,” she says. “But a farm? I can’t bear to think about it.”

Even those who do get into small animal medicine are not always happy. Early-career vets face grueling work schedules and task lists that may have little to do with their field of study, says Ma, the head of a pet hospital in the northwestern city of Xi’an who asked to be identified only by their surname for privacy reasons.

Ma described a list of duties interns are expected to complete, including cleaning up fecal matter, dog walking, and janitorial work. These menial tasks, combined with the shock of seeing mistreated or seriously ill pets, can cause burnout among more idealistic students.

“When you do these things day after day, you start to wonder why you got into the industry,” Ma says.

Money matters

The typical veterinarian career track looks something like this: four to five years as a student followed by an internship, then a period as a veterinary assistant – first junior, then intermediate, then senior — followed by promotion to resident, then outpatient doctor, attending doctor, and finally director or associate director of a hospital.

In theory, rising through the ranks can take a decade. In practice, constant turnover can lead to rapid advancement for those who manage to survive the first few years. Ma, the hospital chief, has been in the field for just five years. She estimates that of the 180 people in her graduating class, fewer than 10 are still working in animal hospitals. The rest have either found work in the pharmaceutical or research roles or left the field altogether.

“The industry is very young,” Ma says. “New graduates can advance quickly.”

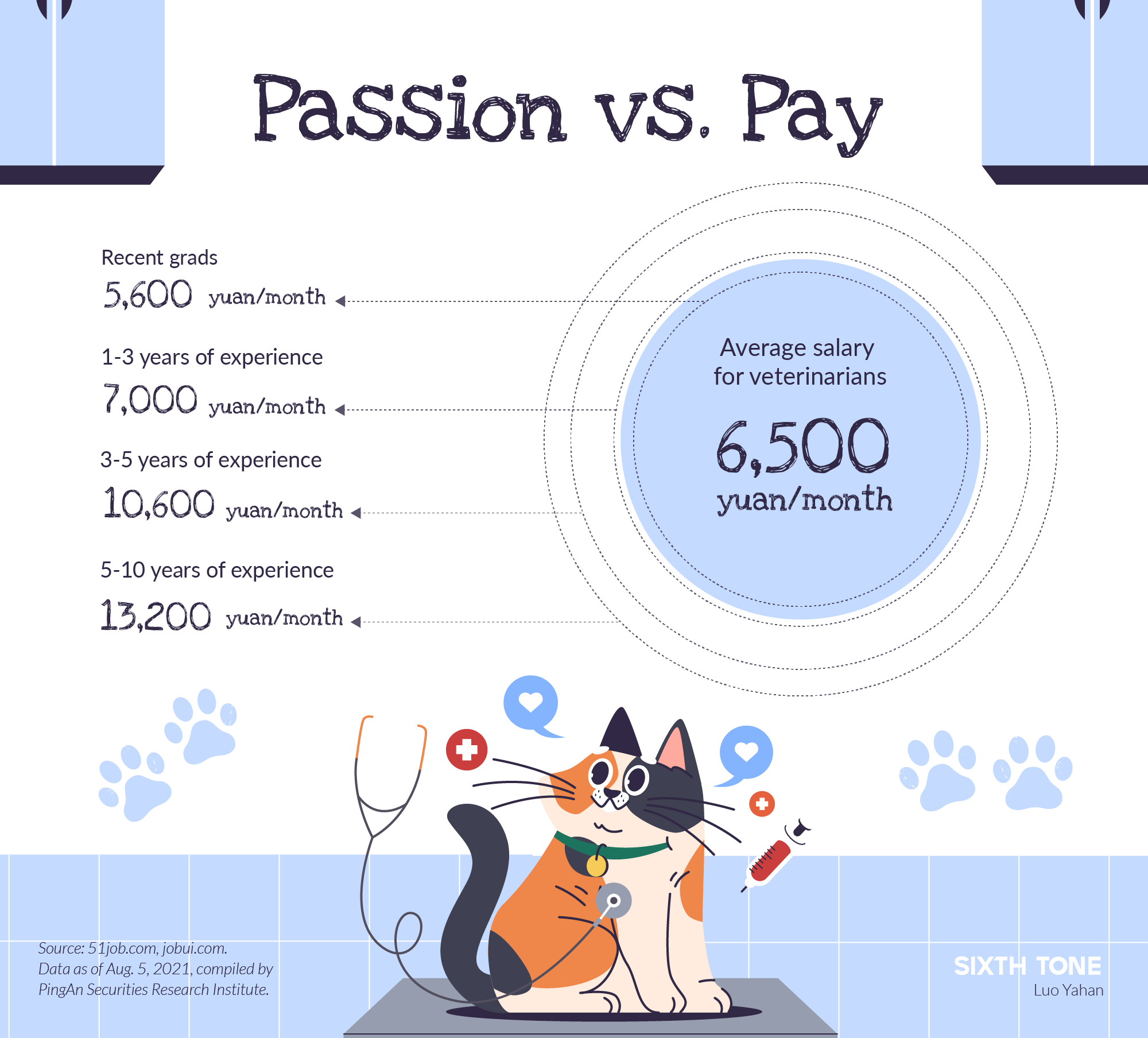

One of the biggest hurdles for early career vets is the low pay. Despite the lengthy training process, the average entry-level vet in Shanghai earns just 5,000 yuan ($700) a month, according to a report by Ping An Securities, while the average newly minted university graduate in the city earns 6,700 yuan.

At this point in her career, Ma earns almost 10,000 yuan a month, which she says is more than enough in a city like Xi’an. But reaching that point can be tough, especially for recent graduates who haven’t passed their licensing exam. “If you can’t get a vet license, you can only work as an intern, which means a salary of 2,000 to 3,000 yuan a month,” she says. Licensed vets make more, but their pay still lags behind other industries for the first several years of their career.

That’s what happened to Yang. After graduation, she got a job as an intern in a large pet hospital where she made 2,000 yuan a month. She described the work as grueling, with 12-hour shifts that left her no time to eat. Between the pay and the workload, she felt she had no future in the industry.

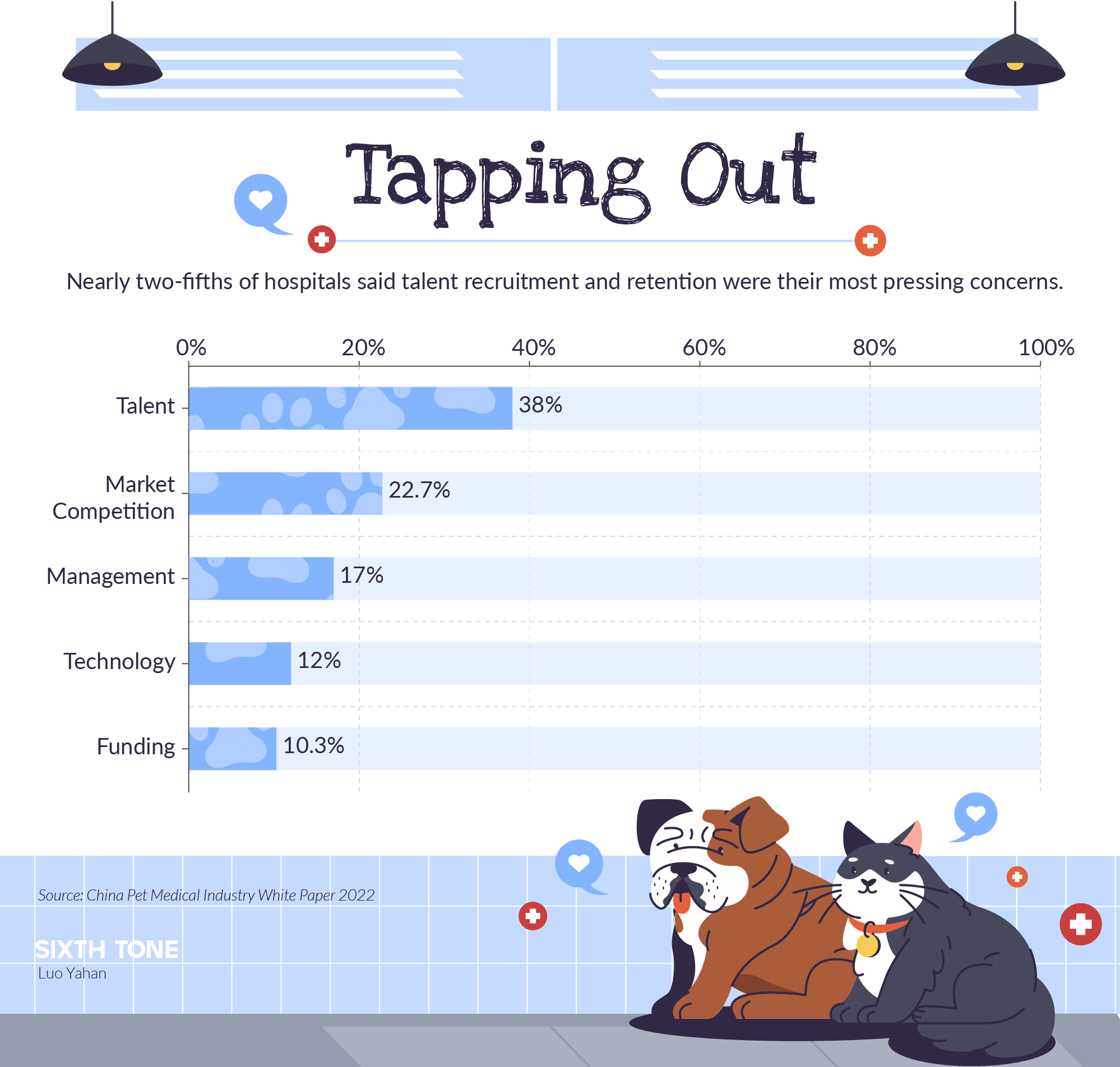

These departures are having an adverse effect on pet hospitals, even as demand for their services continues to rise. According to China’s 2022 Pet Healthcare Industry White Paper, published in 2023, the most commonly cited issue facing pet hospitals is talent. More than half of the surveyed hospitals reported trouble retaining staff.

Professional associations have tried addressing the problem by offering continuing education programs targeted at getting young vets credentials that can help them advance more quickly. Last year, a training program run by the Chinese Veterinary Medical Association added 44 new classes and issued over 22,000 credit certificates.

Better academic tracking was also mentioned as key to solving the retention problem in almost all the interviews Sixth Tone conducted with students and industry figures, with most advocating for clearer lines between large and small animal specialties.

Ma says that universities should do a better job separating students according to their interests, allowing them to pick a specialization — whether medicine, husbandry, or biology — after their first two years. Although Chen, the student, ultimately opted to specialize in large animal care, she appreciated that her school gave her the choice, saying that the split programs helped students identify their interests and get a head start on their chosen profession.

Another option would be for schools to help students find internships involving clinical practice. The key, Ma believes, is reminding young vets what attracted them to the profession in the first place. “The sense of accomplishment and satisfaction I feel when I’ve cured a pet is unparalleled,” she says. “And that’s true for any veterinarian.”

(Header image: VCG; illustrations: pikisuperstar on Freepik.)