The Surprisingly Complex History of Shanghainese Cooking

One of the overlooked stars of “Blossoms Shanghai” — Wong Kar-wai’s hit TV adaptation of the award-winning novel “Blossoms” — is the food. The show’s sumptuous aesthetic offers viewers a glitzy look at the dining culture of ’90s Shanghai, from the protagonist’s glamorous Cantonese-inspired restaurant to the ubiquitous roadside stalls that once served up heaping portions of noodles, rice soup, and starchy cakes to hungry workers.

Unsurprisingly, local restaurants have tried to cash in on diners’ nostalgia with menus featuring dishes from the show. The famous Fairmont Peace Hotel has launched a nearly 1,500-yuan ($200) set menu based on “Blossoms,” including sea cucumber, catfish, and stir-fried noodles. Foodies with lighter wallets have descended on the city’s once prosperous Huanghe Road neighborhood in search of cheaper eats.

But the search for authentic Shanghai cooking is complicated by a lack of consensus. What exactly is Shanghai culinary culture, if such a thing even exists? Ask a local and the response will almost certainly be benbang cuisine, a term with a long history but a somewhat mediocre reputation. Or perhaps it’s the more refined-sounding “Shanghai cuisine,” itself something of a misnomer due to its roots almost everywhere but Shanghai. But even that might not be good enough for contemporary diners, as some eateries have begun adopting the term haipai cuisine, a reference to the city’s cultural fusion of East and West.

Close to home-cooked

Let’s start with the oldest of Shanghai’s culinary traditions: benbang cuisine. Literally meaning the “local gang” or “local clique,” benbang dishes are characterized by classic East China techniques like braises, stir fries, and steaming, as well as the liberal use of oil and soy sauce.

Benbang cuisine did not emerge fully formed, but rather incorporated flavors and seasonal ingredients traditionally found in the towns and cities of the Yangtze River Delta region and further south.

For example, the first month of the Lunar New Year brings rice cakes, greens like shepherd’s purse, and meat wontons, as well as roast pork with dried bamboo shoots. As spring begins to bloom, clams appear on dinner tables and fresh bamboo shoots replace their dried counterparts. Summer means sticky zongzi dumplings, melons, and barley tea, then taro, freshly harvested rice, and green soybeans in the fall. Finally, the return of winter brings with it peak season for hairy crabs, fattened pigs, and vegetables like water chestnuts.

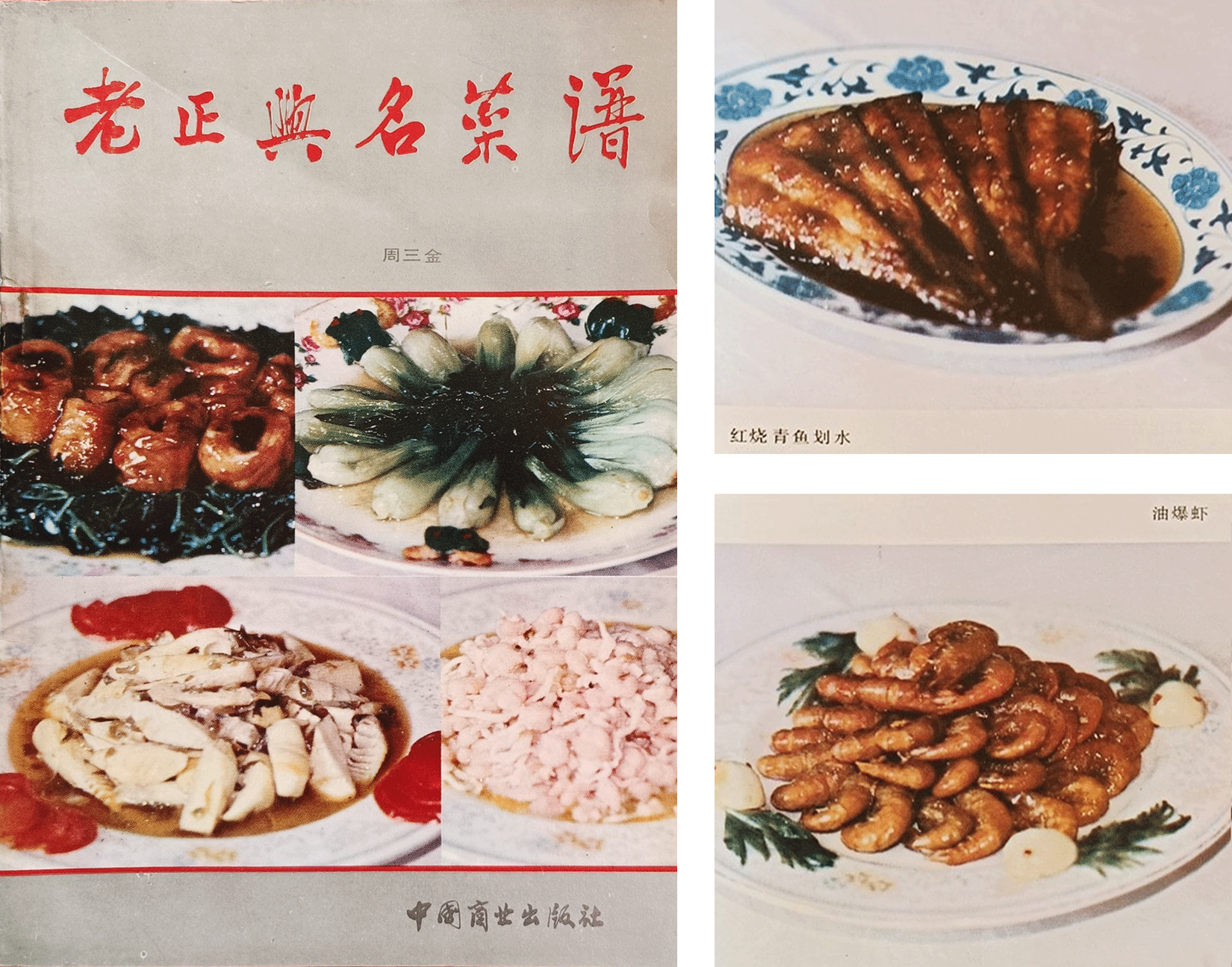

One of the unifying themes of these seasonal menus was availability. Benbang cuisine was simply whatever was affordable in Shanghai at a given time of year. Now venerable benbang restaurants like Lao Zheng Xing, Lao Fandian, and De Xing Guan began in the 1870s as small establishments offering home-style dishes like salted pork and tofu to working class Shanghainese.

A Shanghainese way of eating

For a show so tightly linked to Shanghai’s past, it might seem odd that the protagonist of “Blossoms Shanghai” runs a Cantonese restaurant. Outside of benbang cuisine, what’s thought of as “Shanghai cuisine” is really an amalgam of dishes from commercial centers across China and around the world; it’s more of a descriptor for the food and drink available in the city than a distinct culinary tradition in its own right.

Most of the first restaurants in Shanghai specialized in dishes from the neighboring Jiangsu, Ningbo, and Anhui regions. Establishments offering Suxi cuisine — dishes from the nearby cities of Suzhou and Wuxi — sought to embody the idealized life of wealthy literati with luxurious decorations and refined, sweet-tasting dishes. Anhui eateries also popped up all over the city, offering unique preparations like duck wontons.

But it was seafood-heavy Ningbo cuisine that dominated the city’s food culture prior to the 1930s and ’40s — a side effect of the rise of the city’s “Ningbo clique,” members of which were prominent in Shanghai’s banking industry.

Their influence only faded after the 1930s, when the Ningbo clique was displaced by a rising group of merchants from the southern province of Guangdong. These entrepreneurs opened the city’s largest department stores, helping propel the rise of Cantonese food in the city.

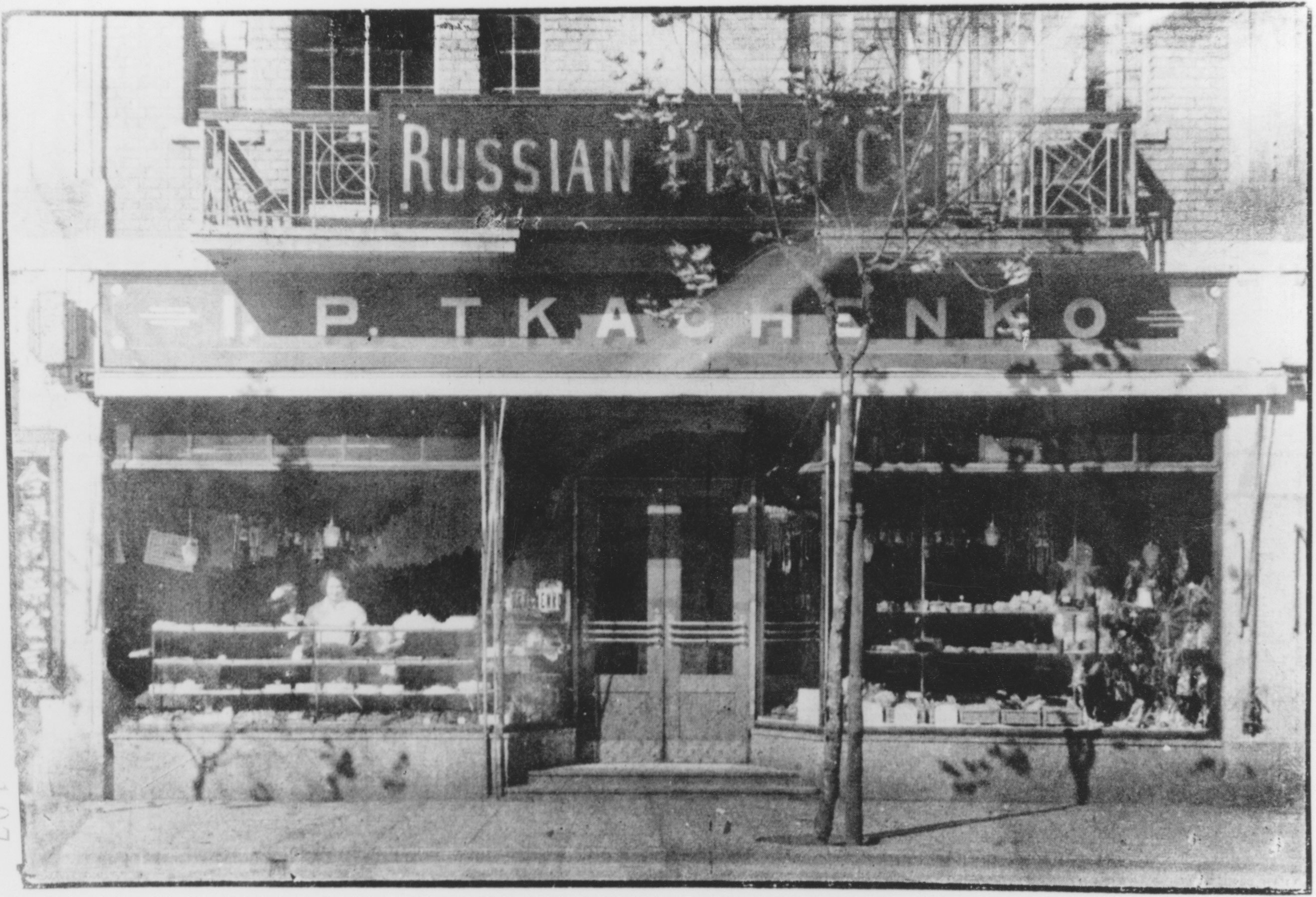

Not all Shanghainese cuisine is Chinese, either. One of the most classic examples of the genre is a heavily localized version of borscht. Known to locals as “Russian soup,” it was brought to the city by aristocrats fleeing the Russian Revolution. Eventually, Chinese cooks began adapting it to local tastes, substituting the beets for tomatoes and pork for beef.

Time to rebrand?

In the early years of the reform period, no one was quite sure how to market Shanghainese cooking. Some advocated for a return to the benbang flavor palate, while others preferred the more legible Shanghai label. In the meantime, Cantonese restaurants like the one featured in “Blossoms Shanghai” experienced a resurgence in popularity with the city’s wealthier diners.

More recently, local chefs have sought to counter this trend by rebranding Shanghai cooking as something called haipai cuisine. The term — literally “Shanghai style” —was originally used to describe the way the city blended the best elements of both East and West, as well as Shanghai and the rest of China. The idea is to tone down some of the more eccentric aspects of the city’s culinary scene while adapting dishes from elsewhere — all with a focus on quality over quantity.

For example, haipai restaurants might cut the amount of oil and soy sauce found in traditional benbang dishes; downplay the spiciness of Sichuan-inspired courses; merge the sweetness of Suxi cooking with the focus on umami found in Ningbo cuisine; and offer a wider selection of fruits and vegetables, in line with Western preferences. The final result is a mixture of different tastes and flavors from various regions — all served on a single table.

Translator: David Ball.

(Header image: A pork chop and rice cakes, two dishes common in Shanghai, 2020. VCG)