China Introduces Sweeping New Controls Targeting ‘Ultrashort Dramas’

Chinese authorities are reportedly planning to dramatically tighten supervision over “ultrashort dramas,” in a move that insiders expect may dampen the industry’s breakneck growth.

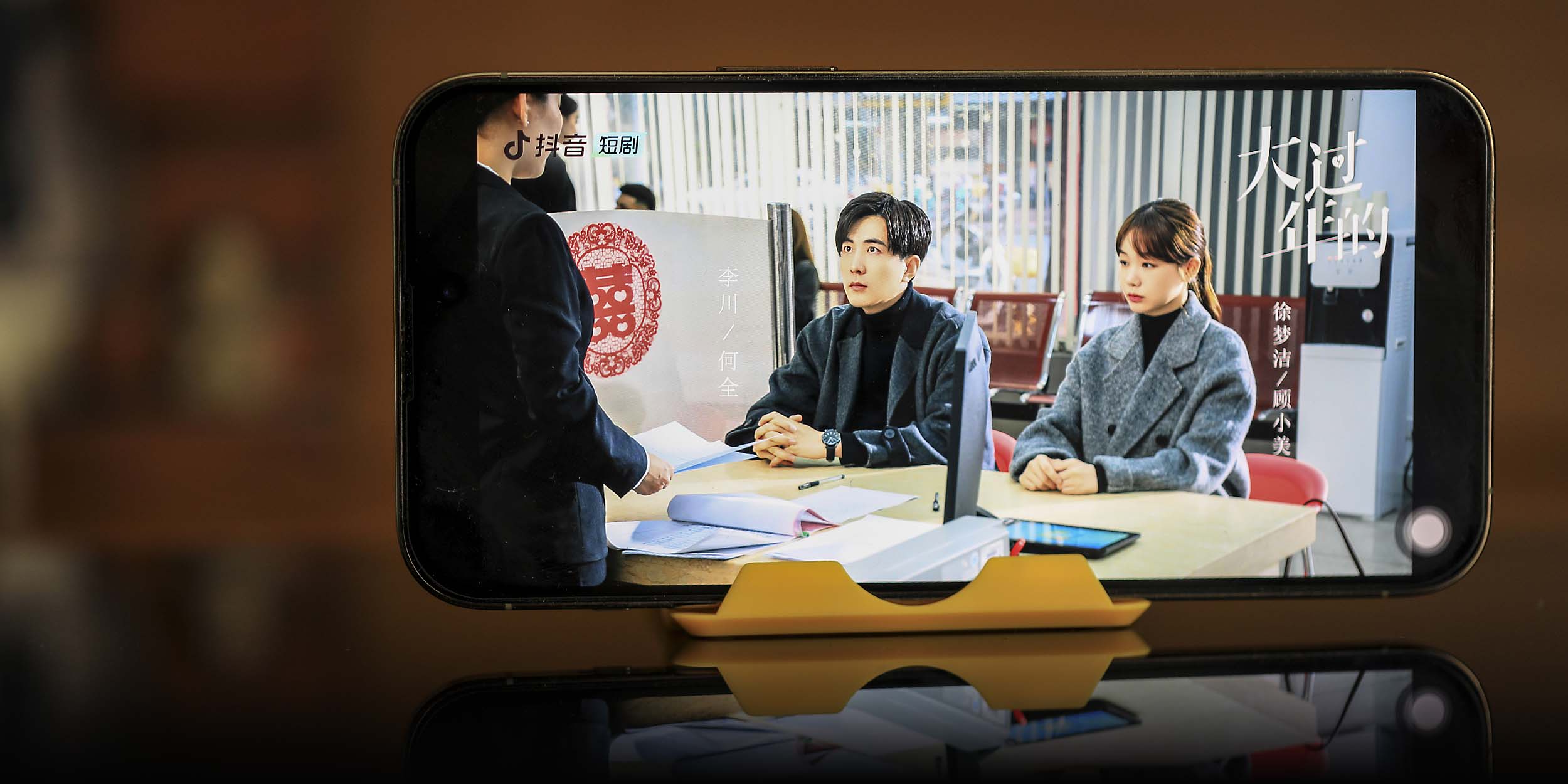

Ultrashort dramas — cheesy, over-the-top soap operas divided into bitesize episodes less than 10 minutes long — have exploded in popularity in China over the past few years, with the market reportedly growing nearly 270% in 2023.

Unlike traditional TV shows, ultrashort dramas are filmed specifically to be viewed vertically on a smartphone. They tend to be fast-paced, racy, and melodramatic, with each tiny episode finishing on a cliffhanger.

Streaming mostly on video platforms like Kuaishou and Douyin, the genre has already produced several big hits. Last month, a show about a stepmother who found herself transported back in time to the 1980s blew up on Chinese social media, a related hashtag receiving over 1 billion views on microblogging platform Weibo.

Starting from June 1, a new supervision system will be introduced that will effectively ban ultrashort dramas that have not been reviewed and approved by the authorities, media outlet Caixin reported on Thursday.

The National Radio and Television Administration has yet to release the new rules publicly, but a document outlining the system has been circulating widely online. Sources told Caixin that some provincial authorities have already implemented the rules and forwarded the document to industry insiders. Domestic media outlet 21st Century Business Herald confirmed the authenticity of the document with a regional official in the radio and television administration. The official confirmed they had sent the document to local production companies and media platforms, but didn't reveal further details.

According to the document, all ultrashort dramas must now pass through a three-tier review system before being distributed online. “Key ultrashort dramas” — those with a budget of over 1 million yuan ($138,000) or touching on “special” themes — will be reviewed directly by the National Radio and Television Administration, while smaller projects will be screened by provincial authorities or streaming platforms. Any drama that has not passed through this review system must be removed from circulation.

The new system will mark a major change for the industry, bringing it into line with other parts of the Chinese entertainment ecosystem. Yan Min, the manager of an online community for ultrashort drama industry insiders, told Sixth Tone that ultrashort dramas had mostly only been subject to reviews by streaming platforms previously.

But rumors of a regulatory tightening have been bubbling since last year, Yan added. Regulators had previously voiced concerns over the industry. Between November 2022 and February 2023, the National Radio and Television Administration drove a campaign against what it dubbed “illegal dramas” that led to more than 25,000 ultrashort dramas being removed from circulation. And the pressure has continued this year.

In March, officials singled out the ultrashort drama “Teachers, Don’t Run,” a drama about a love affair between two school teachers, for its vulgar and pornographic content. On Wednesday, Douyin and Kuaishou announced they had removed another batch of shows that had promoted “improper” family values.

Going forward, it remains to be seen what the new supervision system will mean for an industry that has seen extraordinary growth in recent years.

According to a report by research firm iiMedia, the ultrashort drama market was worth 37.4 billion yuan in 2023 — equivalent to nearly 70% of China’s box office revenues that year. By 2027, the company predicted the market would be worth over 100 billion yuan.

Some industry insiders expect the new rules to dampen the industry’s growth, at least in the short term. Liu Kaiping, an ultrashort drama producer, told domestic media that the mandatory approval process would slow the release of new shows and make it more challenging to score big successes.

But Liu added that the rules could facilitate the long-term development of the industry, making producers focus on quality and explore a more diverse range of themes.

Yin shared a similar view, telling Sixth Tone that he had heard several people voicing confusion and concern over the new regulations. But these negative views were mainly coming from newcomers to the industry, while veteran insiders tended to be unfazed by the supervision policy, he said.

Despite their runaway popularity, producers were already struggling to generate profits from ultrashort dramas. Revenue mainly comes from convincing viewers to pay to watch a show — the first few episodes are often given away for free, and then viewers have to spend a few yuan per episode to see what happens next.

But the massive number of shows being released means that production companies have to invest large sums in marketing. Li Jiang, president of studio Dianzhong Tech, told domestic media recently that more than 80% of the firm’s revenues were being spent on promoting content.

With China’s ultrashort drama market becoming increasingly saturated, Chinese producers have increasingly been looking abroad for new opportunities. According to market consultancy Sensor Tower, the overseas ultrashort drama market will be worth around $2 billion by 2025.

(Header image: VCG)