Why Chinese Are Studying Solo, Together

Two years ago, on a typically windy and cold winter day in Beijing, I ducked into a shared workspace in the city’s wealthy Haidian District. Hosted in a nondescript office building surrounded by apartment blocks, the space was tucked away in a maze of small hairdressing, printing, and photography shops. Stepping inside, I was greeted by the sound of absolute silence. Everyone was immersed in their laptop or books; no one so much as glanced in my direction.

Feeling like a trespasser, I navigated the space carefully so as not to disturb their focus. There were no on-site personnel to direct interlopers such as myself. Instead, essential information like seat numbers and facilities rules were posted on a bulletin board or provided via an app — a problem when you don’t know the Wi-Fi password. At a loss, I cautiously tapped the shoulder of a young man nearby, breaking his concentration and earning myself a withering glare. When I asked my question, he stared at me in total silence for five or six seconds before dismissing me out of hand: “I’m not the facilities manager, so why are you asking me?” Taken aback, I murmured an apology before scuttling away.

I had clearly violated an unwritten rule of the space, but it would be some time before I fully understood the magnitude of my mistake. Over the next six months, I would visit a total of 13 of these workspaces — known in Chinese as “shared self-study rooms” and marketed toward students, recent grads, and the unemployed — across Beijing and the northwestern city of Xi’an.

The more time I spent within their sterile confines, the more I came to believe the man’s angry response to my question wasn’t an isolated case, but part of a trend toward asocial behavior and an intolerance for disruption among China’s overstressed youth. In a country increasingly concerned about “involution” and cutthroat competition for limited resources, I wasn’t merely a distraction, but an obstacle to his success, however remote that prospect might have felt to him in the moment.

Shared spaces for lonely people

The first self-study rooms emerged in Japan and South Korea in the 1980s before appearing belatedly on the Chinese mainland in 2014. Their popularity soared after 2019, due in part to the popular Korean drama “Reply 1988,” whose protagonist is a frequent patron of self-study rooms, as well as the pandemic, which closed many campus buildings. By 2021, there were some 5,000 self-study rooms scattered across almost every province in the country.

The typical self-study room is austere by design, meant to offer clients only a space for study and nothing more. Most business owners want to keep their budgets low, and they prefer to outfit rooms simply with rows of standardized study cubicles, small cabinets for storage, and little else. Many are operated out of small residential apartments that have been retrofitted into self-study rooms. Like a co-working space, people can pay to rent a seat by the hour, day, or even an entire year, with prices varying from 20 to 100 yuan a day ($3 to $15) depending on location, facility, and brand.

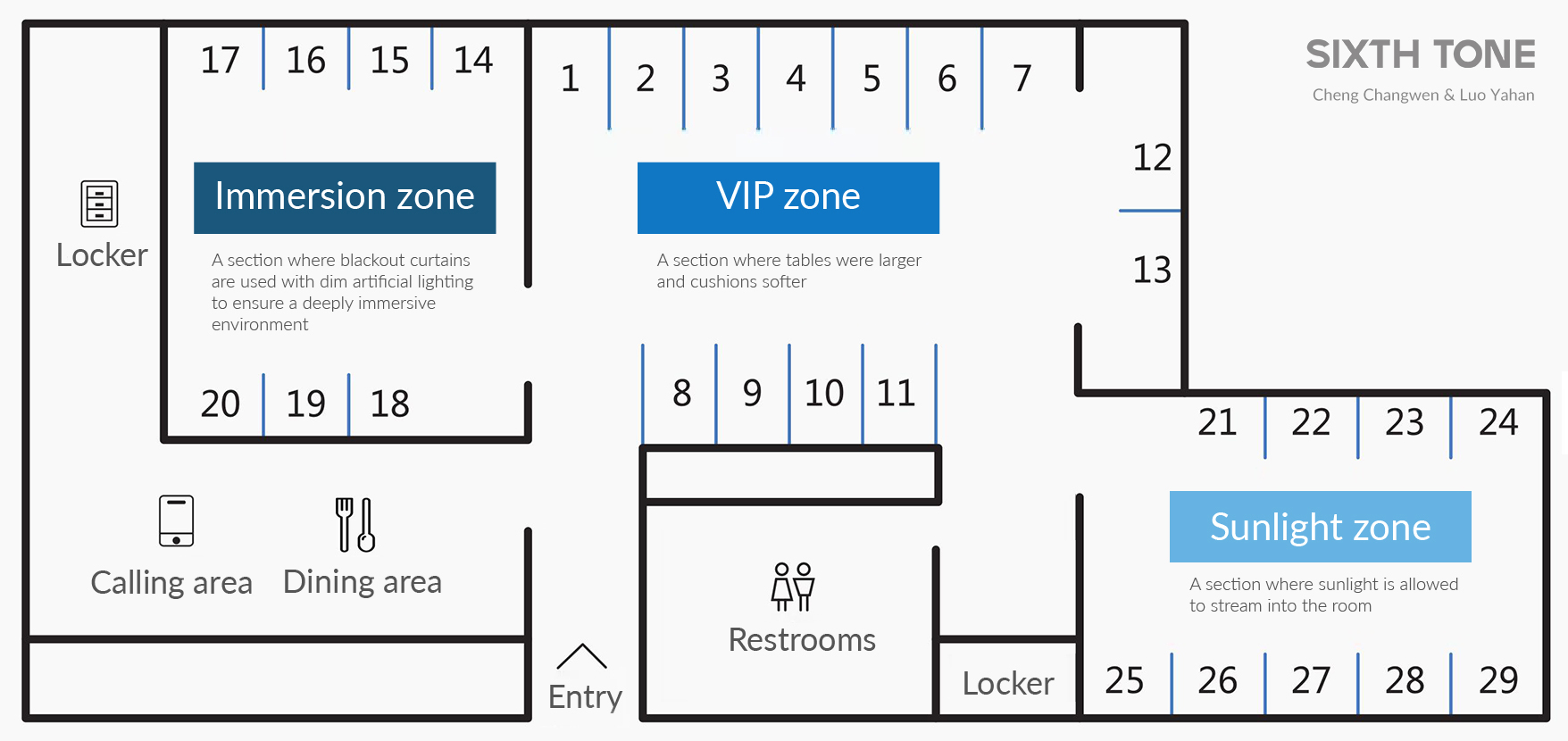

While self-study rooms share superficial resemblances to shared or communal workspaces like WeWork, they do little to foster interpersonal sharing or communication. Instead, everything is designed to minimize social interactions and interruptions. A manager of three study rooms stressed that these spaces are more than just cubicles and desks; they have been intelligently organized, with special attention paid to how each object might distract clients.

That includes even details like trash can placement. “Every seat in my room is equipped with a trash can,” the owner explained. “You might think: this is for the users’ convenience, right? This is just one consideration. The other reason you wouldn’t guess unless I told you: It’s to reduce walking and thereby minimize distractions for others.”

And because these rooms are at their core for-profit enterprises, care is taken to cater to different needs and types of students. The self-study rooms I visited used relatively similar furniture, but most zone their space into different areas, creating nooks that varied in the intensity of light, levels of noise, and types of seats.

It may seem like overkill, but this culture appeals to individuals like Beibei, a recent college grad who failed her first attempt at the national postgraduate entrance exam. No longer a student, she needed a new place to study as she prepared to retake the exam. Home and other public spaces were out — under immense pressure, she viewed them as too distracting for her purposes. “When you’re studying, everything seems so enticing, and I find myself gravitating towards lying down on the bed whenever I feel a bit bored,” she explained.

Beibei saw study rooms as a much better alternative for what she called “real work.” There, the disruptions from home fade away, while there was a minimal risk of intrusive social interactions.

A bittersweet experience

This desire to maximize attention spans and eliminate interruptions can be understood in the context of increasing competition in the Chinese job market, where higher education certificates can no longer guarantee a good job. Over 4.5 million people took the national postgraduate entrance examination in 2021, up nearly threefold from a decade prior. Roughly 1.42 million people took the highly competitive national civil service exam that year, up 40% from 2020.

Most failed. The enrollment rate for the national postgraduate entrance examination hovers around 30%, meaning that two out of three candidates will confront the difficult decision of whether to attempt the exam again or enter the job market directly. The statistics for the civil service exam are even more daunting. It is not uncommon to come across news reports about hundreds of candidates vying for a single position.

Education is key to staying ahead of the competition, which explains the tense atmospheres in many self-study rooms. Many learners have rigorous study plans, with timetables detailed down to the minute. Interruptions could ruin an entire day’s studying schedule.

Zaozao, a 25-year-old woman who works as an accountant in a government-sponsored institution, explained the pressure this way: “I feel that life is divided into many stages. When I fail to reach the next stage, I feel that my life has been stagnating. Therefore, I will be very anxious to reach that goal as soon as possible so that I can carry out the next step of life.”

Given that Zaozao already holds a coveted government-sponsored job, her response may seem surprising, but she still believes she needs to enhance her educational background to advance her career and be prepared for potential layoffs in the future — ideally by pursuing a master’s degree, either in China or abroad. This determination stems from a painful lesson she learned from her mother, who spent most of her life working as a nurse in a public hospital before being laid off in the 1990s.

Zaozao’s idea of a linear life trajectory, punctuated by milestones, is a view held by many Chinese young adults, even among those who have already seemingly attained the ultimate goals of job security and stability. Having been raised in a test-centric educational system, they see failing to study and pass an exam as proof they are “stagnating,” or falling behind. Conversely, being attentive and having the capacity to study means more than simply passing an exam — it means that one can move up and proceed to the next stage of life.

The positive, if somewhat harsh, side of this belief is that any pain experienced during the studying process becomes tolerable and even desirable. Posts on Zhihu, a question-and-answer platform popular among educated Chinese, often reaffirm the necessity of enduring suffering when people talk about the unbearable experience of studying. “The right course of action often runs contrary to our natural instinct,” one poster wrote. “Only things that feel insufferable and difficult can bring about the transformative change desired.”

Another Zhihu poster suggested that it is irrelevant to ask how suffering can be reduced because pain is both a “sweet” and “inevitable” part of self-improvement. Without suffering, there can be no progression.

The downsides of this outlook become evident when we observe the rise in mental health issues among Chinese youth in recent years. At least since the rise of marketization in the 1980s, social mobility in China has become heavily reliant on education. This has cultivated a strong individualistic belief in success and the idea that knowledge can alter one’s fate. The flip side of this is the need to constantly compete with one’s peers or risk being left behind, leading to what Chinese have taken to calling “involution.” The constant need to study has become an onerous burden that is leaving many people feeling hopeless and useless, especially if and when it doesn’t pay off.

This relentless competition is exhausting, and with social mobility no longer as easily achieved, individuals are increasingly turning to self-study rooms for safe harbor. These spaces hold out the promise of self-development and improvement, even as they encourage people to wear themselves thinner and thinner.

There are, of course, other responses to this phenomenon. Already, some have challenged the hamster wheel of endless study by “lying flat.” But doing so requires financial security and the wherewithal to ignore societal norms, and is not an option for everyone. For the rest, there’s the endless race forward.

This article was based on the author’s research. To protect the identities of his research participants, he has given them all pseudonyms.

Portrait artist: Wang Zhenhao.

(Header image: A study room. Courtesy of the author)