Last Stop: Looking Past the Stigma Facing China’s Morticians

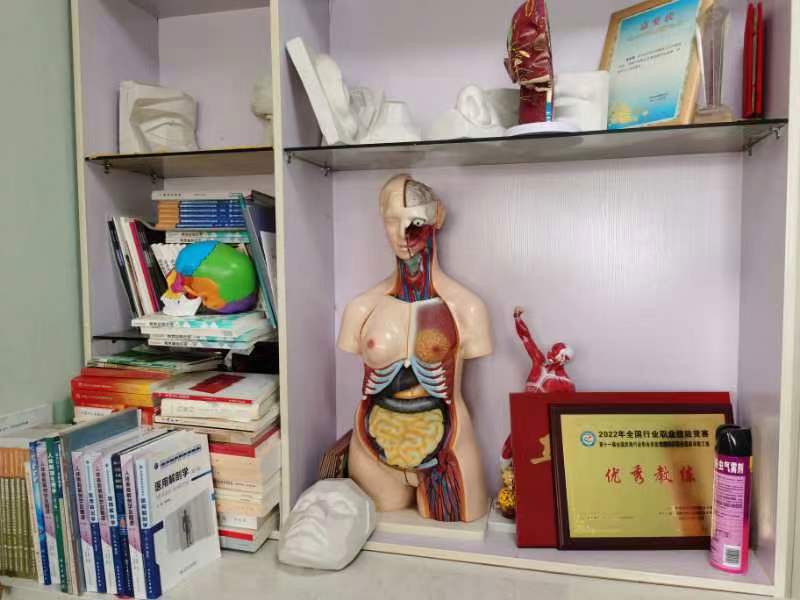

Sitting on Zha Qingguo’s desk is a skull — a plaster model of his own skull, to be exact. A macabre sight for most visitors, perhaps, but for Zha and his colleagues, it’s a training tool. It comes in useful whenever they are required to piece a real skull back together.

Zha’s job as a mortuary technician is not for the faint-hearted. Over 25 years working at Shanghai’s Yishan Funeral Home, he’s become highly skilled in the art of embalming and cosmetically preparing bodies for burial, which sometimes can involve extensive reconstruction. He sees himself as a “ferryman,” gently guiding the deceased on their final journey to the other side.

Yet, while he has excelled in the workplace, earning regional and national awards for his professional dedication, in life Zha has long had to endure the stigma attached by some sections of Chinese society to those who work with the dead.

“I don't go out or socialize much. Many people consider this line of work taboo,” says the 52-year-old, who adds that some of his colleagues are reluctant to discuss their work or even reveal their profession to others, even friends. They rarely receive wedding invitations, and during the Chinese New Year holiday, they are usually unwelcome in the homes of neighbors and relatives because of cultural beliefs about avoiding “inauspicious” people and things for fear of bringing bad luck onto the family. “Even when you greet people from a distance, they will still try to evade you,” Zha says.

Anecdotal evidence suggests this kind of treatment, coupled with the nature of the work, has for years made it hard for mortuaries and funeral homes to attract and retain young employees.

Zha has had several apprentices, but each one has eventually left the profession. He recalls one young man who had the impression that working at the funeral home offered a stable job with decent pay, so he asked a connection to introduce him. “From the very start, he was fearful and wouldn’t touch the bodies. We tried to encourage him, but he was always afraid. Every time he touched a body he would jump like he’d received an electric shock. He had nightmares after his first shift, and after that he was dispirited and listless for days. He resigned after a week.”

There was also a female university student who was initially assigned to reception duties but later transferred to the cosmetology team. “She was far more composed than the young man, and she gradually adapted to the work here,” Zha says. “But she started dating someone, and when he found out she worked at the funeral home, he broke up with her. So, in the end, she also decided to leave.”

Early days

Zha himself stumbled into the world of funeral homes. Born in the southwestern metropolis of Chongqing, he moved to Shanghai in 1993 and began looking for work. He took on several informal jobs, but none of them lasted long. Eventually, five years later, at the age of 27, he was hired full time at a flower shop in a funeral home.

He remembers that summer being extremely hot, with temperatures soaring to 38 degrees Celsius. The mortuary was full of bodies, and he was constantly delivering flower baskets, making wreaths, and doing various odd jobs. “The senior technician saw that I was a hard worker and able to handle tough conditions, so he transferred me from the flower shop to the funeral home’s cosmetology department,” he says.

At first, being young and strong, he was assigned to “peripheral” roles, such as handling and transporting bodies. However, his supervisor advised him to begin developing some specialized skills, which would allow him to accomplish more with less effort. Like many others, Zha was afraid of coming into contact with the deceased at first. “I’m not someone with a weak stomach, but feeling the cold temperature of the bodies was unsettling for me, especially bodies in an advanced state of decomposition. I felt like the smell clung to me wherever I went.”

Within about three months, Zha had already adapted. “The senior technician told me that this job is highly stigmatized and many people look down on it, but it has its value. Regardless of our status in life, every one of us will eventually reach this stage, life’s final stop. So this job is worth doing, and it’s worth doing well.”

He took his mentor’s words to heart. “Before this job, my life had always been unstable. But now I have a stable life. I took his advice and committed myself to doing a good job,” he says.

Zha began to study the craft alongside the senior technician and quickly moved from the team’s periphery to its core. In 2003, a professional qualification for embalming technicians became available, but Zha wasn’t qualified to take the examination because he did not hold a Shanghai household registration. Although disappointed, he didn’t waste any time; while others were attending classes and preparing to sit the exam, he found materials to learn from and studied on his own.

He started with basic human anatomy, and then delved into dissection, pathology, and embalming. He read dozens of books on funerary practice and medicine. He even studied sketching, sculpting, and aesthetics. If something was remotely related to his field, he would read up on it in search of skills and techniques to apply in his work.

As soon as the professional qualification exam in Shanghai was opened to non-residents in 2005, Zha passed with flying colors.

Restoring dignity

In addition to having to cope with the social stigma, the day-to-day work of a mortuary technician is also often immensely challenging.

In 2004, two fresh high school graduates drowned while swimming in a river. When their bodies were finally recovered from the water, they were bloated beyond recognition. Their grief-stricken families pleaded with the mortuary workers at the Yishan Funeral Home to restore them to the way they had looked in life, so that they could be laid to rest.

“There was a cadaver preservation research institute at the funeral home, and we were researching this topic at the time, so we agreed,” Zha recalls. In the industry, bodies in this condition are referred to as “giant cadavers.” Several technicians spent over half a month shut in a small workroom brainstorming solutions. Initially, they thought restoration would be straightforward, but they were wrong.

They started by injecting embalming fluid and placing the bodies in a refrigerated unit, but this failed to return them to their normal size. Then they tried injecting more embalming fluid and bringing the bodies up to room temperature, but still the bodies remained severely bloated. “We were at a loss,” Zha says. “Then we thought about household refrigerators, which sometimes have a low-temperature storage space between the freezer and refrigerator section for perishable items. So we checked if it was possible to apply this technique to the cadavers.”

After half a month of low-temperature refrigeration, the bodies had finally returned to their normal proportions. For the grieving families, seeing their children restored to their original appearance provided some solace, and they were extremely grateful for the team’s efforts.

Another case that remains vivid in Zha’s memory is when he had to reconstruct the face of a woman who had been killed in an accident involving a construction vehicle. It was a devastating scene; her skull and facial bones had been shattered, rendering her unrecognizable. Her grieving husband asked the funeral home’s technicians to help restore his wife’s appearance.

“The woman’s skull had been completely destroyed, so we had to sculpt a new one, which was something we had never done before,” Zha says. Although the bone fragments were difficult to piece back together, Zha and his colleagues refused to give up. They referred to studies of skull structure in anatomy books while trying to restore the women’s skull piece by piece like a puzzle, using plaster to reconstruct the missing parts, which took them two full days. Then they replaced her skin and stitched it into place. When the husband saw the result, he gripped Zha’s hands and thanked him over and over.

“The reality of this job is that it involves forensic knowledge, so we are constantly expanding our boundaries,” he says. Although such a challenging restoration required several technicians to work through the night, nearly collapsing from exhaustion, being able to comfort the bereaved family members by giving them the chance to see the woman returned to her original appearance made it all worthwhile. “Preparing the deceased for a viewing that maintains their dignity is a way of showing compassion and respect for life.”

Despite the challenging conditions involved in working in a mortuary, Zha feels the general perception of the industry is changing, with fewer people now having a negative impression. “People’s views on death are changing, and society is increasingly recognizing the value of our industry,” he says.

Today, he leads a team of six technicians at the Yishan Funeral Home, four of whom are aged between 35 and 45. For his long service in the field, last year, Zha received the National May 1 Labor Medal, which is presented by the All-China Federation of Trade Unions in recognition of a worker’s outstanding contribution, and he has been honored with the title of Shanghai Craftsman by the city’s trade union.

“When I started in this industry, the senior technician told me that by preparing the deceased for their final goodbye, we’re caring for the remains of their life and soothing the pain of their loved ones. I like to pass on these words to my younger colleagues,” he says. “The deceased cannot speak, but we treat each one with gentleness and equality, giving dignity to the departed and giving the memories to the living.”

Reported by Wang Haiyan.

A version of this article originally appeared in the Shanghai Observer. It has been translated and edited for brevity and clarity, and is republished here with permission.

Translator: Carrie Davies; editors: Xue Ni and Hao Qibao.

(Header image: VCG)