In Shanghai, a Café Blends Life, Death — and Coffee

Since 2008, Liu Xing had avoided discussing the traumatic memories from the Wenchuan earthquake, where he volunteered as a medical student. Sixteen years later, he found himself reliving those experiences with a group of strangers at a small, quiet coffee shop in Shanghai.

The death and devastation in China’s southwestern Sichuan province had even driven him to switch his major from medicine to advertising. “A 7-year-old child and a 70-year-old had the same expression: hopeless, gazing with unusually wide, lifeless eyes. It felt like they were just machines,” 35-year-old Liu recalled about the survivors he met then.

In May, Liu was one of two guest speakers at Ferryman café, which hosted its first memorial event for the disaster that caused over 69,000 deaths. After a mourning ceremony and short speeches by Liu and an expert from an international rescue and relief organization on facing unpredictable disasters, each guest shared their experience with death.

Run by a Shanghai-based funeral service company of the same name, the coffee shop offers a rare space for the public to learn about the funeral industry and discuss one of China’s biggest taboos — death.

Due to fear and superstitious beliefs, many Chinese still believe that merely mentioning mortality might invite misfortune. Parents avoid discussing it with their children to shield them from harm, and people go to great lengths to avoid the number four, which phonetically resembles the word for death in Mandarin.

Despite more individuals, particularly the young and middle-aged demographic, beginning to talk about death more openly and taking steps like drafting wills, many still struggle to understand how to handle death when it inevitably occurs.

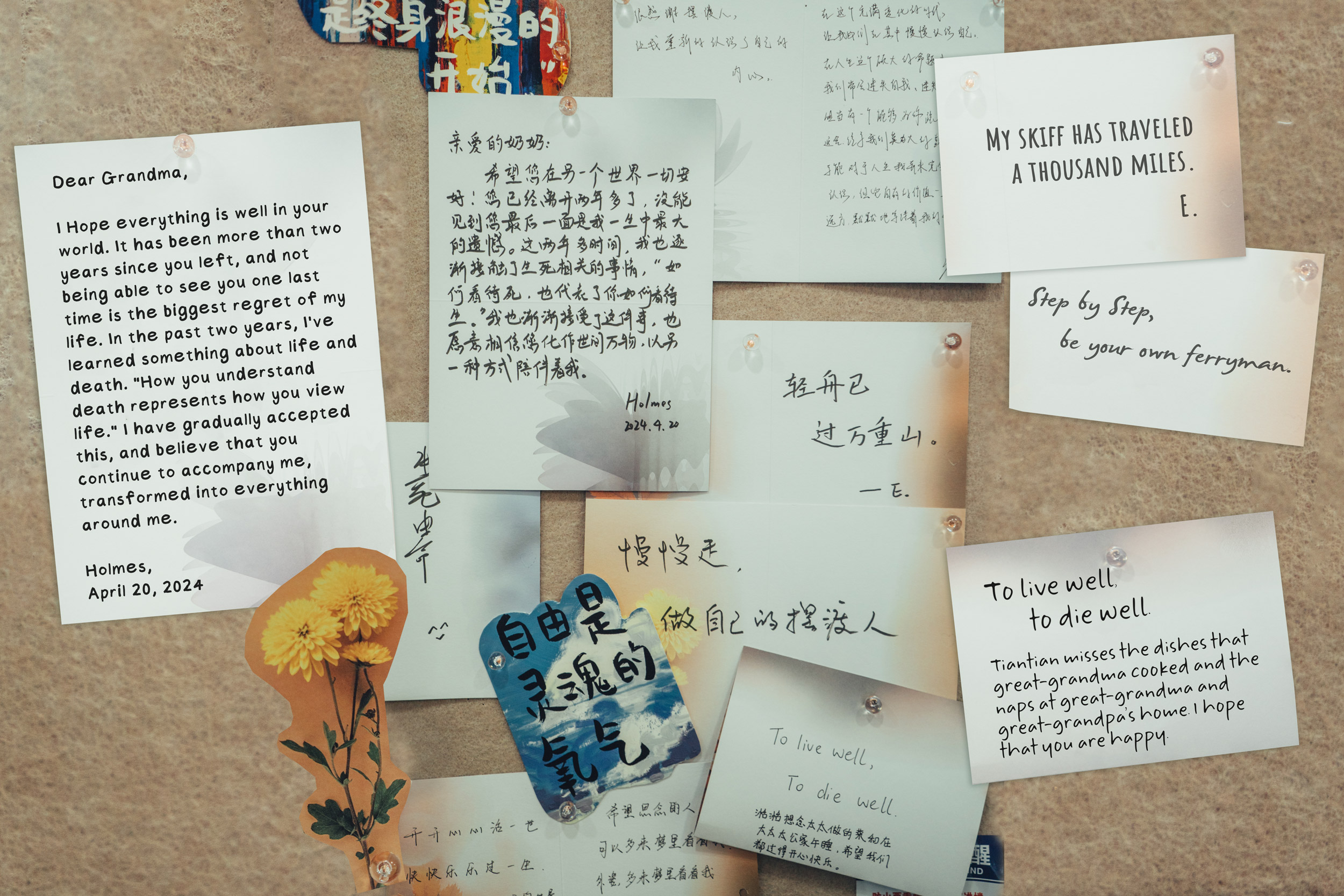

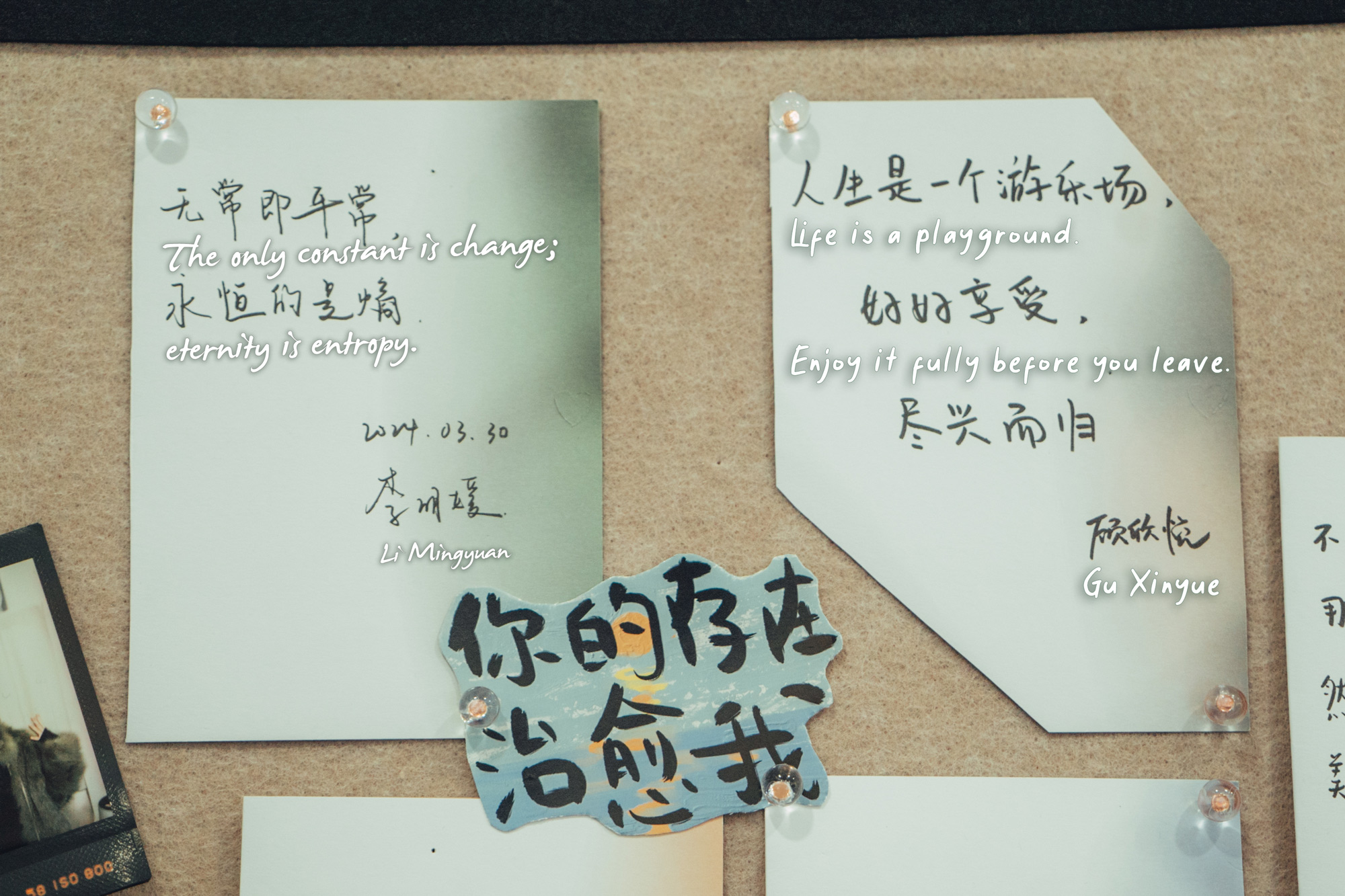

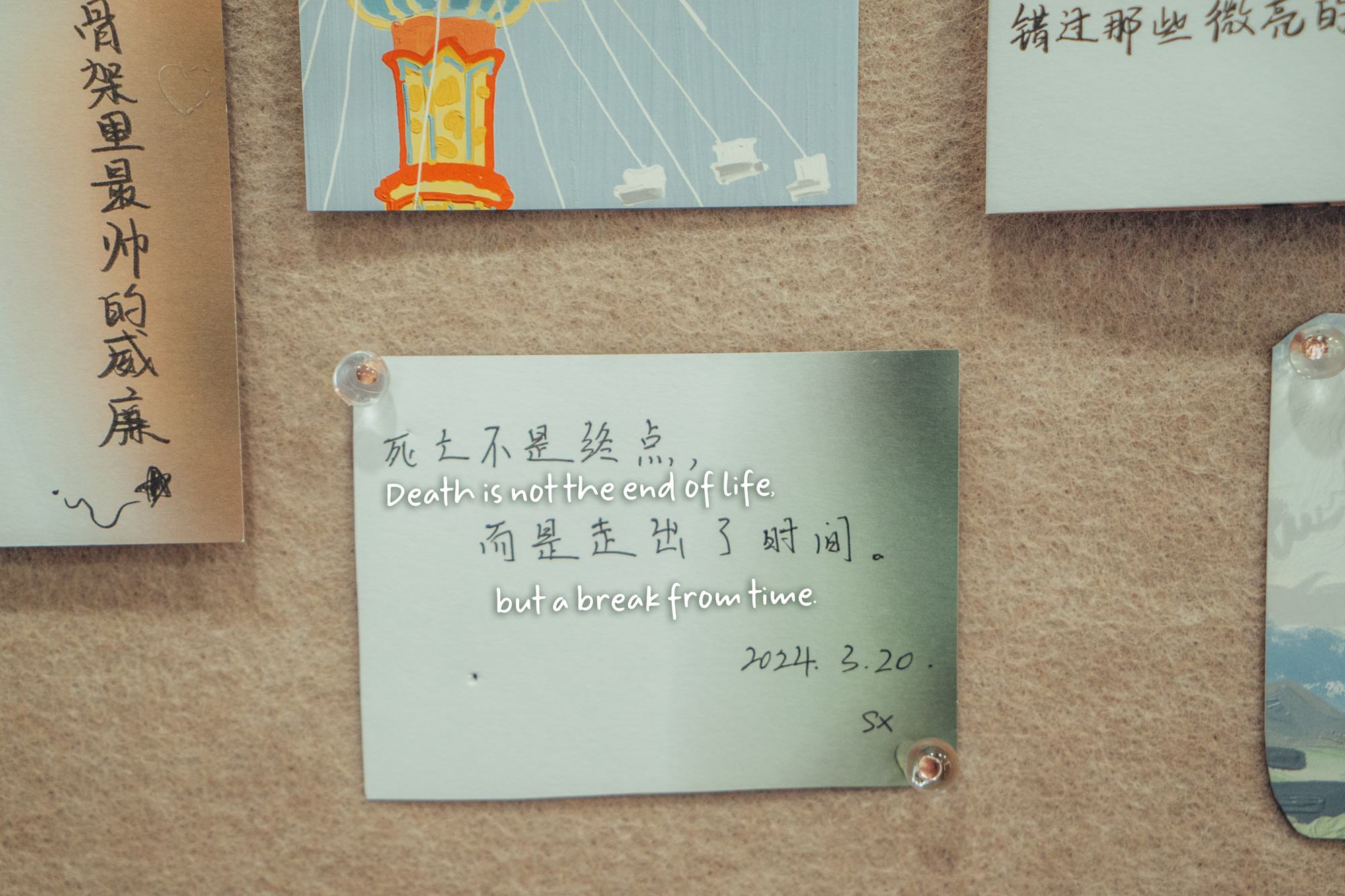

But at Ferryman café — named for the figure who ferries souls between worlds and helps solve problems in Chinese folklore — conversations about death are encouraged and embraced. Over free coffee, patrons are encouraged to exchange personal stories and perspectives on death.

According to Shi Xiaolin, who heads the coffee shop project, the Ferryman café is also part of the funeral service company’s efforts to educate the public about the funeral business and diminish the negative perceptions of the industry in China.

“We hope that the concept of ‘exchanging stories for coffee’ will encourage people to open up their hearts,” says Shi. “Many have something on their minds but may not be able to express it immediately in an unfamiliar environment or with unfamiliar people.”

Since opening in February, the Ferryman café has drawn numerous curious customers like Liu, quickly putting it under the spotlight on domestic social media platforms, where many dubbed it a “Death Café.”

While some online view the ability to openly discuss death at such a venue as a symbol of social progress in China, others argue that combining such a serious subject with a casual coffee-drinking experience is a gimmick that brings a sense of “ill omen.”

The intense public attention and controversy surrounding the coffee shop led Ferryman café to temporarily suspend operations for a few weeks in April. But amid fervent requests to visit, the Ferryman team resumed its free coffee service in early May.

Despite now running nine stores, it wasn’t easy for Ferryman to find suitable locations for its funeral service storefronts. Since its establishment in 2017, the team has faced challenges in selecting locations due to society’s stigma surrounding the funeral industry.

According to manager Shi, many believe places used for funeral services are undesirable for other businesses to rent. They secured the location for the café with the help of a former customer.

The taboo surrounding death has also led to a significant information gap in the funeral industry, she says: Many profit-driven funeral businesses have exploited this lack of transparency, resulting in hidden service fees, exorbitant funeral prices, and unlicensed operations.

“The ‘one-stop’ funeral service providers in the old days often treated the dead with disrespect,” explains Shi. “For them, the funeral was just a job to make money by exploiting people’s lack of knowledge.”

Following several incidents in recent years, China moved to tighten regulations on the funeral industry, and mandated clear pricing information for all services and products.

Introducing a coffee shop along with funeral services was aimed at redefining the industry, though it may not bring extra revenue. “We just want to shatter the negative perceptions of the funeral industry and bring it into the light for positive development,” says Shi.

The Ferryman café operates by appointment, accommodating seven visitors daily, with walk-ins when available.

In the past three months, Sun Linguang, an event manager at Ferryman responsible for accommodating customers and making coffee, has met hundreds of visitors who confide in him.

“It has enriched my own life experience after listening to so many people’s stories. It’s made me think more about how I should live,” says Sun. “The visitors here are also a kind of healing for me.”

For every special event, Sun prepares a unique selection of coffees, each symbolizing an aspect of life — sweet for joy, sour for disappointment, bitter for hardship, and spicy for challenge.

At the memorial event on May 12, Sun made these four kinds of coffee as usual, and each participant was asked to answer five questions to introduce themselves after tasting the drink.

The first four questions focused on participants’ names, self-descriptions, their connection to Ferryman, and their expectations from the visit. The fifth question asked, “How would you spend your remaining time if tomorrow were the last day of your life?”

The event drew nine participants, including Liu Xing, from varied backgrounds — college students to coffee shop owners. Despite their differences, nearly all shared a common experience: the loss of family members.

“We can happily celebrate new lives, but we rarely have the occasion, scenario, or time to calmly discuss death with a group of people,” a 27-year-old participant tells Sixth Tone under the pseudonym Xiao Ye. “It is very meaningful and special to openly discuss death in such a scenario.”

Although recalling his volunteer experience during the Wenchuan earthquake is still traumatic for Liu, he appreciates the opportunity to share his story at Ferryman.

For him, discussions about life and death can help people understand death and how to face the sudden loss of loved ones in a fast-paced, high-pressure society. He says: “Death is an objective fact, a law of life, and a law of nature. Once we learn to confront the issue without fear, it will be less difficult to process death.”

Editor: Apurva.

(Header image: The coffee set made at the Ferryman café for events. Courtesy of Sun Linguang)