Should China Develop Manufacturing or Services? It’s Not Either Or

China’s economy is at a critical juncture, sparking ongoing debates in academia about the optimal paths and goals for this transition. A key question is whether China should prioritize development of the manufacturing or services sector. Some local governments have even set targets for how much of their GDP output will stem from manufacturing, effectively pitting manufacturing against services.

However, in my view, manufacturing and services are not mutually exclusive. People who deem it so are not only making a mistake in their economic analysis — they are also failing to grasp what is needed for the next step in China’s economic development.

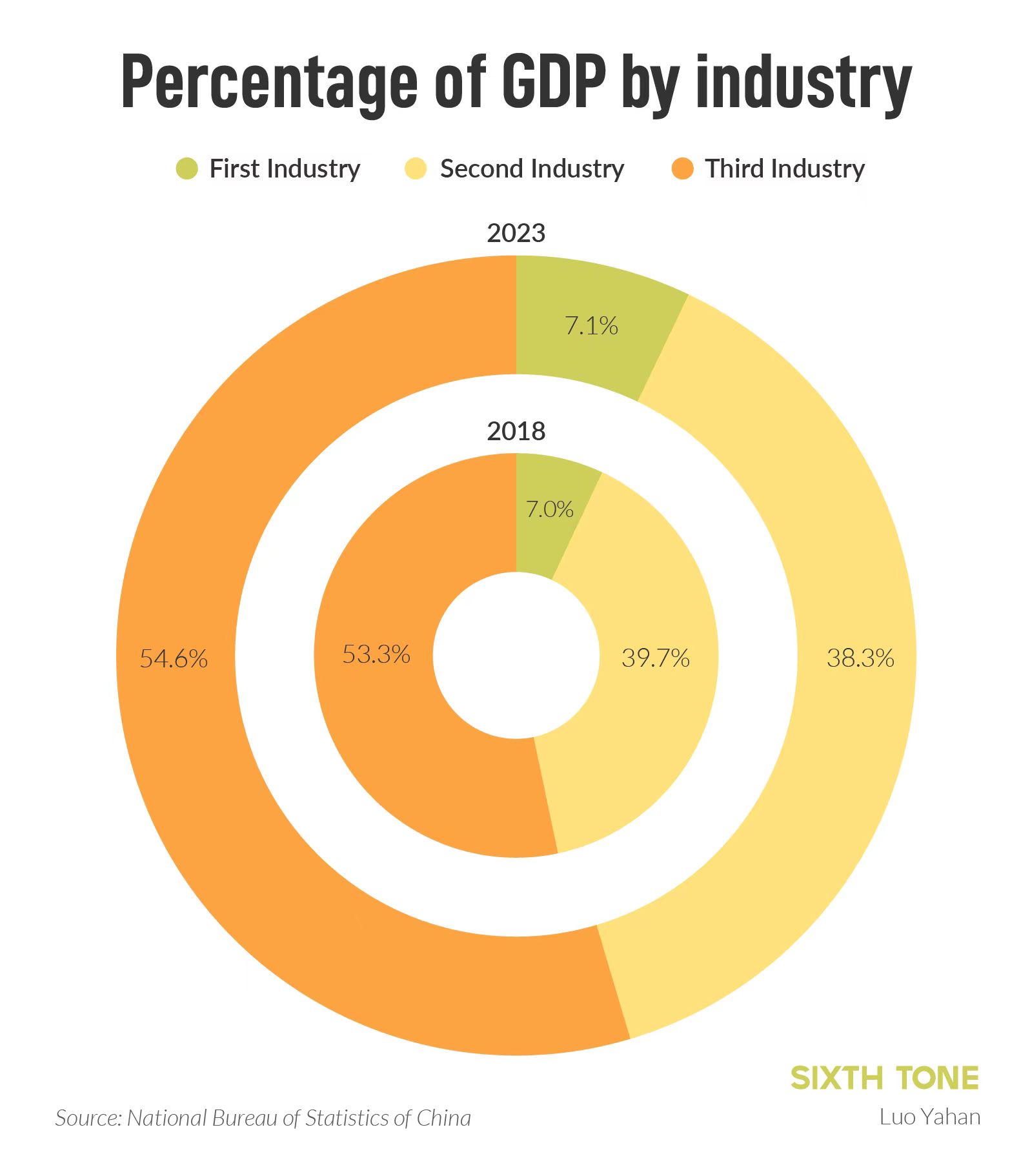

China’s per capita GDP is transitioning from that of a middle-income country to a high-income country. This necessarily requires changes to the country’s economic structures. In terms of industrial structure, the tertiary sector currently accounts for more than half of China’s GDP — 54.6% in 2023 — indicating that the economy has already entered a post-industrial stage.

China is undergoing profound changes, but people’s perceptions and behaviors, from industry to policymakers, often lag behind. If government departments at all levels fail to come to grips with what is happening, China’s economic development will be constrained. The chief issue before us is not whether China will suffer from “Baumol’s cost disease” — employment overly concentrated in the tertiary sector — which will lead to the hollowing out of the manufacturing sector, but rather whether policymakers and the public can break free from certain mindsets formed during China’s previous period of industrialization to effectively meet the needs of a post-industrial society.

Specifically, we should avoid four types of dichotomous thinking:

1. Avoid pitting manufacturing against services

China has a strong tradition of valuing manufacturing over services, which can often mean equating a strong manufacturing sector with having manufacturing be responsible for a high proportion of GDP.

This underlies the popular belief in the 2010s that China should emulate the “German model” of having an export-driven economy with a strong manufacturing base, advocated by leading scholars such as Li Daokui, president of the Institute for Chinese Economic Practice and Thinking at Beijing’s Tsinghua University, and Ding Chun, director of the Center for European Studies at Shanghai’s Fudan University.

However, emulating the German model does not mean maintaining a high proportion of manufacturing in the economy. In fact, Germany’s manufacturing sector is responsible for only 18% of the country’s GDP. Germany is also only roughly the size of China’s Yangtze River Delta region, which limits the applicability of the German model to China.

In reality, the manufacturing and services sectors are more interrelated than some might think. For example, domestic services that use manufactured goods as intermediate products can help absorb some of the overcapacity of Chinese manufacturing sectors that would otherwise be reliant on exports, such as the healthcare sector’s use of medical equipment and machines.

Therefore, we should avoid thinking that promoting the services sector is somehow shifting from the real economy to the virtual or that it takes away labor from manufacturing. Instead, we should look for ways to promote both services and manufacturing.

2. Avoid pitting production against consumption

Economic theory often distinguishes between consumption and production activities. However, in reality, a lot of consumption of services is inherently beneficial for production such as education and healthcare, which increase knowledge and health, thereby boosting human capital.

Consumer-facing industries can also drive technological progress, such as the gaming industry’s development of the metaverse, the healthcare industry advancing biopharmaceutical innovation, and cultural industries improving lighting and sound technologies. Moreover, many services enhance labor productivity by essentially outsourcing household production tasks to the market, such as catering and childcare.

On a macro level, as Chinese cities compete to attract talent, it is smart policy to promote high-quality local services to attract the best talent.

3. Avoid pitting online against offline

The rapid development of the digital economy has led many to worry that the online economy will replace offline activities, even impacting the real economy. In fact, much of the online economy empowers the offline economy.

For instance, livestreaming e-commerce platforms help small-scale producers in the textiles industry expand their market reach, streamline sales, and boost efficiency. These benefits are particularly important in regions with relatively small markets and sparse populations.

Even if online activities do replace offline ones, this is only ever partial as the two economies do not operate independently of one another. A simple example illustrating this is that in urban areas with higher population density, food delivery orders are not only higher in quantity but also in the diversity of options available and the quality of the food.

4. Avoid pitting high-end against low-end

Many people differentiate between “high-end” and “low-end” services such as elderly care and hospitality. While it is true that workers in these industries often have lower educational levels, these “life services” are often essential for the productivity of workers in China’s “high-end” industries.

Life services jobs are also less vulnerable to automation than other sectors, which helps with employment. More importantly, many life services have been transformed by technological innovations, which have expanded the economic potential of these so-called “low-end” industries. For example, household service platforms are using big data to transform in-home services into advertising and sales channels for daily necessities.

Editor: Wu Haiyun and Vincent Chow.

(Header image: Delivery riders in Taiyuan, Shanxi province, March 2024. VCG)