Why China’s Small Merchants Are Checking Out of Mega Shopping Fests

Every June since 2019, Cao Liang prepped his small stationery shop for the “618” festival — China’s second largest online shopping event and a major driver of annual sales. This year, he’s sitting it out.

Despite sales shrinking by 60% and fewer customers visiting his online shop in recent months, Cao knows it’s a high-stakes gamble. But he’s betting on a new strategy to stay afloat.

“I have shifted my focus to the Western market, pursuing quality, and sustainable growth,” the 35-year-old from the southern tech hub of Shenzhen tells Sixth Tone.

For years, such festivals have been synonymous with booming sales, rock-bottom discounts, and promises of increased visibility and traffic.

Now, a growing number of small merchants across the country are stepping back, seeking refuge from the relentless discount frenzy and cutthroat competition that define these shopping sprees.

According to a survey by a domestic media outlet, almost 6% of sellers surveyed nationwide across multiple industries chose not to participate in this year's “618” promotion. These sellers cited a surge in returns, relentless after-sales service demands, and the difficulty of managing the promotion’s intensity and duration.

When asked about their target sales growth, 44% of participating sellers aimed for a modest increase of 10% to 20%, while another 44% set their sights even lower, targeting growth rates below 10%.

The recalibration comes even as major e-commerce platforms intensify their price wars. This year, the “618” sale expanded from a single-day event with a pre-sale scheme to a month-long bonanza, shifting to direct sales of in-stock items. This change requires merchants to have stronger supply chains, better management, and quicker response times.

According to Cao, such low-price initiatives compromise earnings, resulting in profits of less than 10% of revenues, compared to the 20% to 30% he usually earns outside of promotional events.

“Selling more during events can even lead to greater losses, as the risk of refunds increases and drives up related operating costs,” he explains.

Bargain blitz

For Cao, the pressure to slash prices began well before the “618” festival started on May 20, with a barrage of promotions throughout May: First, with Labor Day holiday deals, followed by Taobao’s founding anniversary discounts from May 6 to May 10, culminating in the “520 Day” promotion from May 15 to May 20.

“It is a competition between platforms, but they use merchants as scapegoats,” he says, underscoring the impacts on sellers amid the price war.

His struggles with constant promotions highlight the fierce competition between China’s major e-commerce giants, who have since last year intensified their low-price strategies to drive business growth.

Despite a small rebound in 2023, online retail sales growth has slowed, rising annually by 12% to 15.43 trillion yuan ($2 trillion) last year, compared with 16.5% in 2019.

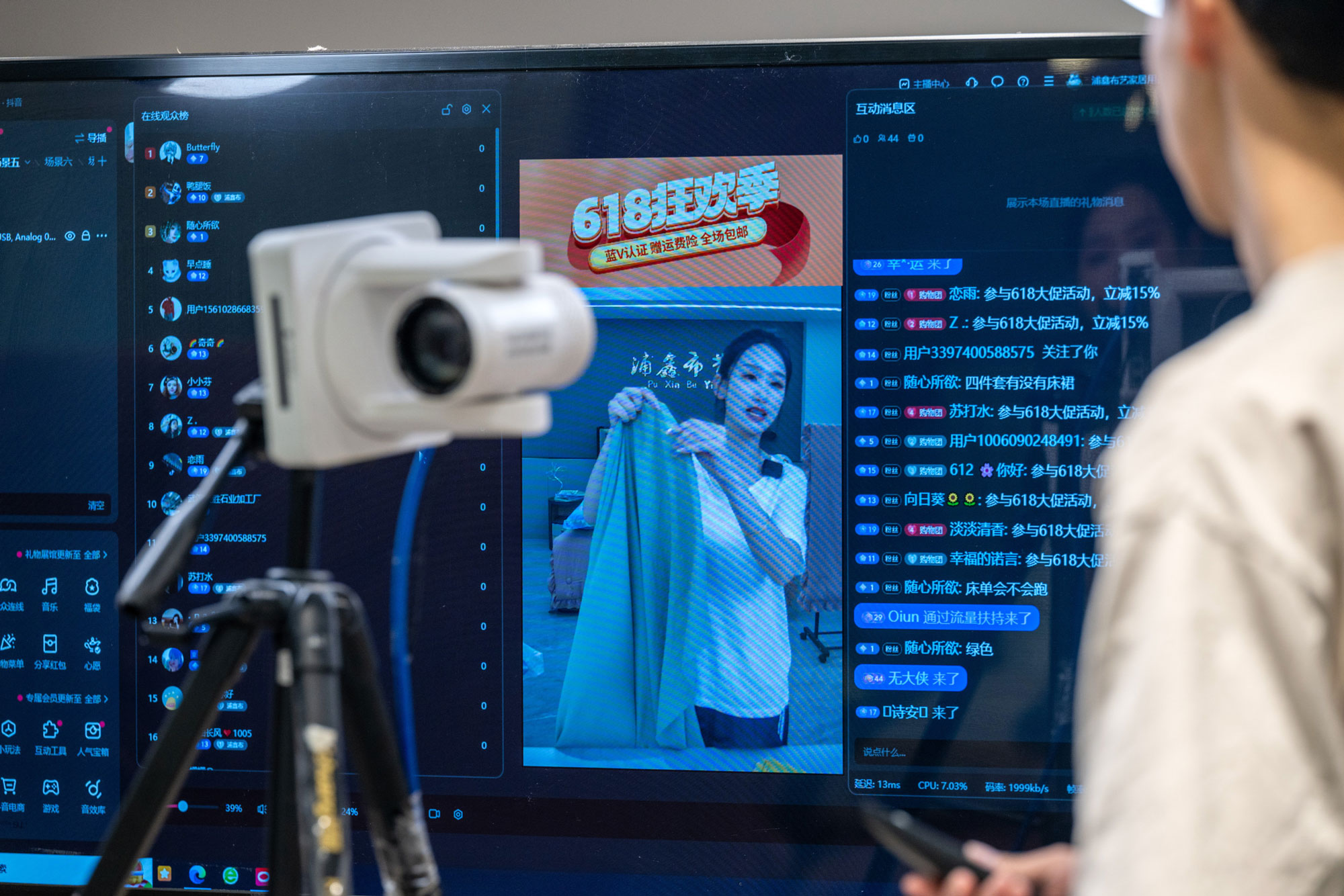

Once dominated by Alibaba’s Taobao — the country’s leading e-commerce platform — and JD.com, the market now faces strong competition from newcomers such as Pinduoduo, known for its group-buying deals and staggering discounts, and short video platforms Kuaishou and Douyin, the Chinese version of TikTok.

Though e-commerce platforms no longer reveal total gross merchandise value, JD.com and Taobao claimed that top brands quickly surpassed 100 million yuan in GMV in 2024.

And according to a survey by Southern Metropolis Daily, 40% of consumers may have spent more than during last year’s “Double 11” festival — the largest annual shopping event, held on Nov. 11 — indicating a focus on finding the best prices.

Amid these optimistic claims, however, reports on low sales margins have gained widespread attention online. According to domestic media, some merchants earned only 550,000 yuan in a year from sales of around 18 million yuan, with some even facing negative profits when following platform pricing advice.

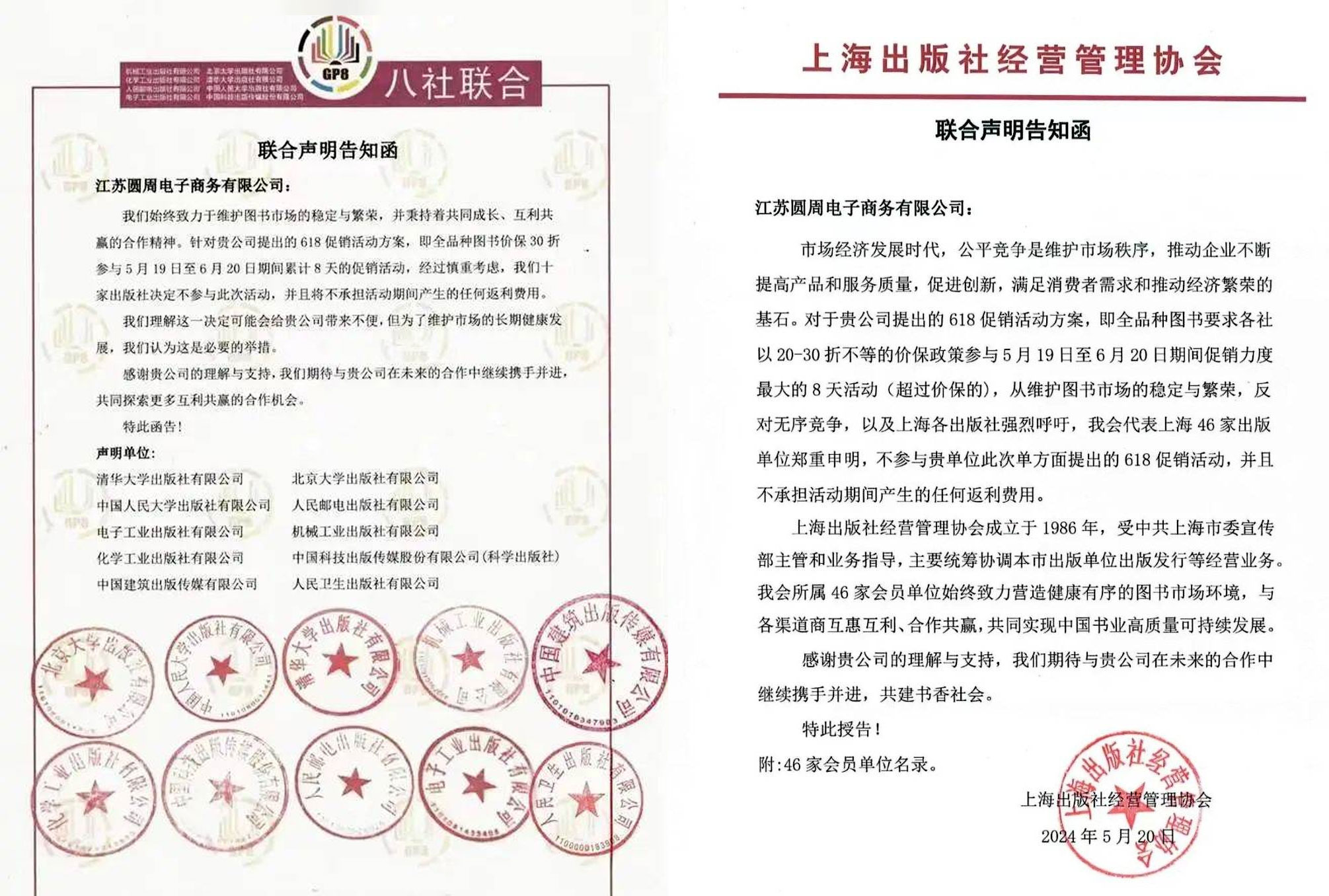

The financial pressures and aggressive pricing strategies have led to significant backlash. In May, dozens of publishers initiated a boycott against JD.com’s “618” event, drawing massive public attention. They claimed that the e-commerce giant demanded universal discounts ranging from 70% to 80% on titles, forcing them to sell at below cost.

Cao explains that it’s a common requirement for merchants to offer the lowest prices online — a strategy whose long-term benefits remain uncertain for small sellers.

While merchants expect sales events to boost customer visits, small vendors say they’re often at a disadvantage compared to their larger, branded counterparts, which have exclusive publicity access and larger marketing budgets.

In-store visits and online sales are usually significantly reduced during major sales events, says Zhu, who co-runs a smaller stationery store online. “Joining sales events won’t help improve the situation much since it’s difficult to increase traffic,” he adds, requesting to be identified only by his surname for privacy reasons.

While Pinduoduo declined to comment on the issue, JD.com and Taobao did not respond to Sixth Tone.

Zhuang Shuai, founder of the Beijing-based consulting firm Bailian, acknowledges the impact of the platform’s low-price initiatives on merchants.

“Merchants are prompted to set low prices in exchange for increased online traffic and scalable sales,” he explains. However, he adds that merchants still have the autonomy to decide their own prices and choose whether to follow these initiatives.

“There are many ways to operate their business, including venturing into other platforms, adopting new business models, or pivoting back to offline sales,” says Zhuang.

Amid the challenges, platforms claim they prioritize small vendors with new support measures. Last June, Taobao announced a unit focused on small and medium-sized business partners, while JD.com pledged that over 150,000 small and medium-sized sellers would achieve 50% more sales with its assistance.

Return roulette

For the merchants who do manage to sell out their products during shopping festivals, the real nightmare begins after the sales: a flood of returns.

In recent months, many sellers say impulsive buying and logistical challenges have led to staggering return rates, turning what seems like a success into a potential financial disaster.

For instance, one viral report revealed that a merchant achieved a turnover of 10 million yuan on Douyin in the first 10 days of the “618” festival. However, the shop’s return rate soared to 73%. It resulted in huge losses, mainly from expenses incurred in labor, delivery, packaging, and service fees to the platform.

More merchants voiced similar experiences, particularly in the women’s apparel market.

Online shop owner Gu Pengge from the southern Guangdong province admits that though his sales increased, the return rate for his store spiked to 50% compared with around 25% during non-event periods.

“It’s tough to make a profit. Not only are my efforts wasted, I also have to cover the shipping insurance. When customers return products, I’m actually losing money,” the 29-year-old tells Sixth Tone. “It’s truly disheartening.”

These returns policies stem from a 2014 government directive, which mandates hassle-free seven-day returns for e-commerce purchases, excluding perishable or virtual products. Buyers must cover delivery costs and ensure products are returned in good condition.

In 2021, Pinduoduo pioneered a policy that allows users to get refunds with or without returning products, which other platforms have since adopted. For instance, Taobao customers can request refunds if delivery exceeds the agreed time or the products are shipped without consent.

On the flip side, consumers argue that they return products for valid reasons.

Chen Xixi from northern Shanxi province said she bought approximately 40 items of clothing during “618,” but returned half of them due to quality issues.

“Some clothes were tailored badly, or the sizes were wrong. Some were made of thick fabric unsuitable for summer, or the fabric was see-through,” says the 27-year-old. “These clothes may look good in the description, but it’s different when you receive them.”

High return rates are also a consequence of rising return abuse, with some consumers buying items with the intent to use them briefly before returning them for a full refund.

In a recent case that made headlines, students from a school in the northeastern Heilongjiang province returned over 400 skirts after a campus show. According to the owner of the online store, most of the skirts had been worn and washed, rendering them unsuitable for resale.

For consumers, the assurance of being able to return unwanted products has become a valued consideration when choosing a platform. According to data from research agency iiResearch, the availability of aftersales and return services ranked as the third most valued factor for consumers when choosing an e-commerce platform in 2023, up from seventh place three years ago.

Taking note of these consumer preferences, Taobao, JD.com, and Douyin have followed Pinduoduo and loosened return policies since late last year.

JD.com has since expanded its “refund-without-return” policy to all vendors on the platform, while Douyin has allowed “refunds without returns” as an option for vendors as of September.

But according to merchants, high returns are not necessarily a reflection of clothing quality but rather customers wanting to select the best option and return the rest.

“When customers make multiple purchases for comparison, the shipping pressure mounts on stores,” explains Gu, the seller from Guangdong. “It’s unavoidable that some products return damaged and are unsuitable for resale. This cost burden ultimately falls on stores.”

In response, online shops are implementing a new strategy: fulfilling only a small portion of orders immediately upon receipt. The majority of orders are held back until returned items from the first batch are inspected, restocked, and prepared for resale.

Once a sufficient number of returned items are available, merchants use these to fulfill the remaining orders. This cycle repeats, leveraging a continuous flow of returns to ensure order fulfillment while helping merchants manage their cash flow more effectively.

However, this strategy has led to longer delivery times, which in turn has started to erode user loyalty.

Chen experienced this first-hand when she bought an item on a pre-sale scheme and waited 15 days to receive it. “I had already bought plenty of clothes when I received it. The longer they postpone the delivery, the less I want the products,” she explains.

Ma Ke, a 28-year-old from central China’s Henan province purchased more than 10 outfits during the 618 sale but only kept three. She plans to shift towards physical stores due to prolonged wait times. “It is a waste of time to wait a month for online purchases.”

Sellers too are pivoting back to offline stores. Confronted with high return rates on Pinduoduo, Gu decided to shut his online store on the budget platform and now focuses on managing his store, using online channels solely to clear excess inventory.

Industry experts contend that high return rates, especially for clothing and shoes, are an inevitable aspect of e-commerce driven by the necessity of try-ons.

Zhuang of consulting firm Bailian emphasized the strategic use of return policies. “Convenient return policies are often used to attract female consumers,” he says. “Both merchants and platforms have been working on addressing return rates and enhancing user experiences. When users can return and exchange items freely, the likelihood of repeat purchases increases.”

Back in Shenzhen, Cao has decided to steer clear of the ongoing price wars, the incessant returns, and the logistics headaches. Instead, he is focusing on enhancing product quality and design, and leveraging branding to retain customers.

Cao has also set his sights on expanding into the Western market, where he earns more per order, and has recently launched his own website. “In this market, consumers value the vendor’s own channel more than a generic platform.”

He asserts, “I have to take this path; otherwise, the store won’t survive.”

Additional reporting: Ding Xiaoyan; editor: Apurva.

(Header image: Visuals from VCG, reedited by Sixth Tone)