Exploring China Studies and Research in Europe Today

On June 20, the World Dialogue on China Studies: Belgium Forum commenced in Brussels, bringing together 60 scholars and experts from China and Europe to discuss issues spanning climate change, artificial intelligence, and various other global challenges facing the two regions.

Ahead of the forum on June 6, Li Bozhong, Chinese economic historian and chair professor of humanities at Peking University, sat with Zhou Wu, vice chair of the Institute of China Studies at Shanghai Academy of Social Sciences, to talk about their experiences and research regarding Europe-China studies and their outlook for how governments from the two sides can better nurture cooperation in the future.

Zhou Wu: The topic of this forum is “China Studies and Europe’s Perspective on China.” In the past, you often traveled to Europe to lecture, and for a long time you were a member of the International Economic History Society’s executive committee, as well as the committee’s only Chinese member. You’ve had a decent amount of interaction and collaboration with the European academic world and possess a great understanding of the state of China studies research in Europe. What is your impression of what the current hot topics and debates are in the realm of China studies in Europe?

Li Bozhong: I know a bit about China studies in Europe. Among what I know is that research on economic history advanced by leaps and bounds in France and the Netherlands in the 20th century. In France, the Annales school rose to prominence. I think that the research the Annales school did was wholly unique in the Western world, and its impact was huge. In the new wave of scholarship that the Annales school set off, research on Chinese history in France also developed, and new ideas and methodologies emerged. On this side of things, the work of Pierre-Etienne Will, a professor at the Collège de France, is representative of this movement; he is likely the highest-ranking living French scholar of China studies today, and his most famous work, “Bureaucracy and Famine in 18th-Century China,” is considered a classic in the West.

Dutch scholars have conducted innovative work in the field of economic history research. They use economic data from various sectors, resulting in a relatively refined and complete understanding of economic conditions. I met Professor Jan Luiten van Zanden at a meeting in 2000, and he inspired me to begin studying research methodology pertaining to historical national accounts. Later, using this methodology, I spent 10 years writing my book “An Early Modern Economy in China,” which was translated into English and published in England.

I think that mutual communication between both Europe and China has advanced greatly.

Zhou: In 2002, when I visited the Harvard-Yenching Institute, I interviewed Professor Philip Alden Kuhn and talked to him about China studies in France. At the time, he had just published the English version of “Origins of the Modern Chinese State,” composed of lecture notes from a series of lectures he was invited to conduct in France. I asked him: “What do you think are the unique characteristics of China studies in Europe as compared with China studies in the U.S.?” He replied, “Don’t look at research on China in France right now. Although it seems that there aren’t as many China scholars in Europe as in the United States, (European China scholars) have the highest level of scholarship in the world.” His opinion echoes the thoughts you just expressed. From your own scholarly practice, especially proceeding from your experiences of transnational scholarship, what kinds of questions do you think China scholars from around the world need to continuously consider?

Li: European and American scholars in the past were particularly innovative with regard to theory, opinions, and methodology, but some scholars overemphasized theoretical breakthroughs and innovation, while authentic research was sometimes somewhat lacking. The French scholars we just mentioned place more emphasis on substantive research, and I think a lot of American scholars are behind in this capacity. From the perspective of the long development of international China studies, both theory and substantive research need to be emphasized; you can’t pay attention to one and neglect the other. We encourage innovation, but we need to avoid applying theoretical modes and methodologies that have already been proven to be problematic in relation to Chinese history. Regarding all theories and methodologies, we should rate them based on their robustness, using the valid ones and avoiding the bad. By deepening our communication between China and the West, we can achieve this effect.

Zhou: Since your time as a graduate student, you’ve had numerous works translated into English and scores of papers published in prestigious international journals on the topic of research on the economic history of China’s Jiangnan region (the area south of the Yangtze River). You’ve always advocated researching Jiangnan from the lens of global economic history, particularly emphasizing the importance of comparative research — why? What type of comparative research do you think truly constitutes science?

Li: I’ll break it down for you. First, the Jiangnan region really is extremely important. When I was a graduate student, Professor Fu Yiling supervised my doctoral dissertation. He told me I needed to first look into “A Category of Articles in East Asian Studies,” edited by the East Asian Studies Center, part of the arts and sciences research center of Kyoto University in Japan. This way, I could better understand the state of international scholarship on the history of the Jiangnan region during the Qing (1644–1911) and Ming (1368–1644) dynasties. After reading it, I realized that among the works collected, which were written in Chinese, Japanese, English, French, and Russian, as much as one-third of the works on Ming and Qing history were about the Jiangnan region. This clearly evidenced the importance and unique status of the Jiangnan region in Chinese history research. Of course, the more researchers there are in this field, the harder the research will be. Thus, if you want to do something no one has done before, you have to adopt a new methodology.

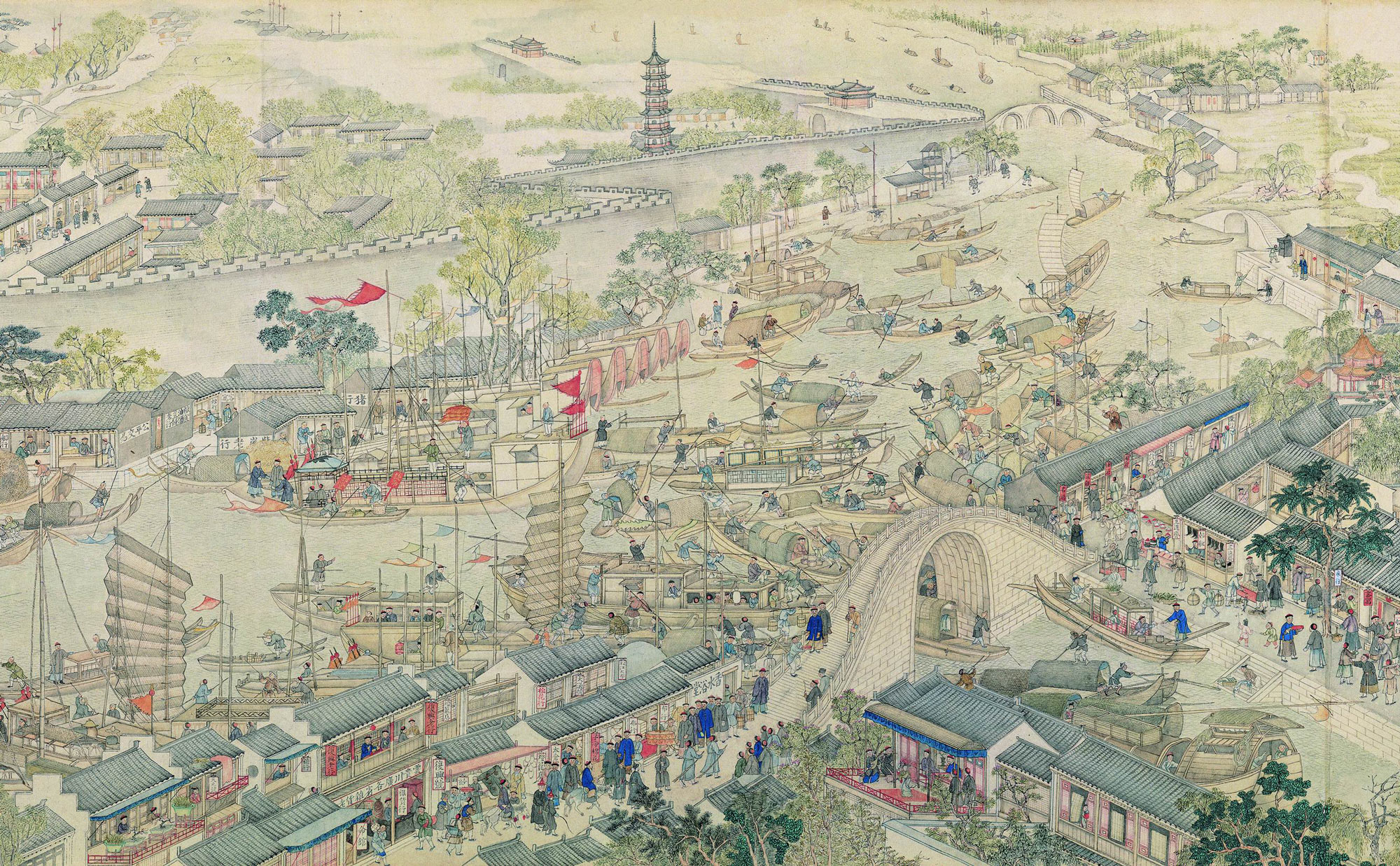

When Western missionaries and merchants first came to China, they arrived in Jiangnan. They saw that Jiangnan was prosperous, the people there were orderly, the scholars and officials refined, and that the teachings of Confucianism were widespread. So, they took this impression back with them to Europe. But as Europeans’ understanding of China deepened, they realized that there was truly a wide disparity between Jiangnan and other regions. I think that the place most similar to Jiangnan in all of Europe is the Netherlands. The surface area of Jiangnan and the Netherlands is about the same, located at opposite ends of Asia and Europe (eastern China versus western Europe), and each is situated at the mouth of a river, the Yangtze and the Rhine, respectively. Both regions are low-lying and full of dense waterways, making transportation easy. On the economic side of things, the two regions were some of the most developed from at least the 17th to early 19th century, with the Netherlands’ GDP per capita being larger than that of England until around 1800, when the Netherlands led Europe in every aspect of technology. And it was like this for Jiangnan in relation to Asia as well. But in the 19th century, the fate of these two regions changed, and they were each surpassed by a neighboring country. Comparative studies between these regions thus enhance mutual understanding as well as understanding of ourselves.

Around 1820, the per capita GDP of Jiangnan was around $1,000, and the GDP of the Netherlands was even greater than in China, around $1,800. At the time, the average GDP in Western Europe (England, France, and the Low Countries) was around $1,100. So, although Jiangnan was not the most prosperous region in the world, it was absolutely one of the most well-to-do. This demonstrates that in the past, China, and especially Jiangnan, certainly wasn’t left behind. Jiangnan had its own inner driving force for development, so it was able to reach a level of prosperity. These elements must be quantified through comparative science, and only then can you see the truth of the past more clearly. This approach aligns with Mozi’s ancient principles of meaningful comparison through measurement. More than 2,000 years ago, he stated, “things that are not of the same category cannot be compared” — but he didn’t say that things of the same category could not be compared. He also said, “speak in quantities,” meaning that when making comparisons, you must use concrete measurements, and only then can a comparison have real meaning. I think that conducting comparative research of these two regions will not only help us understand Europe better but also help us better understand ourselves, providing an objective position.

Zhou: You have written a volume about theoretical methodology: “Theories, Methods, and Trends of Disciplinary Development: A New Approach to Chinese Economic History.” This book particularly emphasizes that the development of Chinese scholarship must integrate into the world. Could you discuss how Chinese academic development can better integrate into the global academic system and gain greater scholarly influence today?

Li: That’s a pretty complex question. Generally speaking, science has no borders because it is the product of collective effort between people. Because of historical reasons, the current international academic norms and discursive systems arose in Europe, and Marxism also originated in Europe. Although the current international academic system has many problems, it has become the system that most countries employ. If we don’t enter the international academic system, then other people will have great difficulty understanding the results of our research, meaning that it would just be us talking to ourselves, which would then make it harder to have exchanges with scholars from other countries. Only by entering this system and innovating academically within it can we obtain greater international discursive power. This is just like how China entered the World Trade Organization (WTO). Not long after we entered the WTO, we became one of the world leaders in trade.

Participating in international academic exchanges, you can neither reject nor follow others blindly. On the one hand, you have to concede its rational and equitable aspects, and on the other, you have to push for change when you encounter irrational or inequitable aspects. The more we have changed for the better on the international academic front, the more discursive power we’ll have. Thus, we must radically open up the academic sphere and not let ourselves become a remote academic island isolated from international scholarship. We must make the world hear our voices, and at the same time learn more from others.

A version of this article originally appeared in The Paper. It has been translated and edited for brevity and clarity, and is republished here with permission.

Translator: Marianne Gunnarsson; editors: Xue Ni.

(Header image: Visuals from VCG, reedited by Sixth Tone)