How China Conquered the Dark Side of the Moon

China’s Chang’e-6 lunar probe has made history by returning to Earth with the first samples collected from the far side of the Moon — a groundbreaking feat that marks a new step forward for the country’s space program.

The spacecraft’s returner module touched down at the Siziwang Banner Landing Site in northern China’s Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region at 2:07 p.m. on Tuesday, delivering its precious cargo of around 2,000 grams of soil samples from the Moon’s dark side, China’s National Space Administration announced.

The mission — whose rocket is named after the Chinese moon goddess, Chang’e — is the latest stage in China’s lunar exploration program, which aims to land astronauts on the Moon by 2030 and build a research base on its South Pole.

Its success has brought that goal much closer to reality, collecting samples that stand to expand our knowledge of the lunar ecosystem as well as road-testing a number of new technologies that will be crucial for future missions.

What is the Chang’e-6 mission?

Chang’e-6 is the latest mission in China’s lunar exploration program, launched in 2004. The previous mission, Chang’e-5, saw a probe bring back 1,731 grams of soil samples from the near side of the Moon in December 2020.

The Chang’e-6 probe was originally intended to be a backup for Chang’e-5. But after the successful completion of that earlier mission, it was given the far more daunting task of collecting samples from the Moon’s far side.

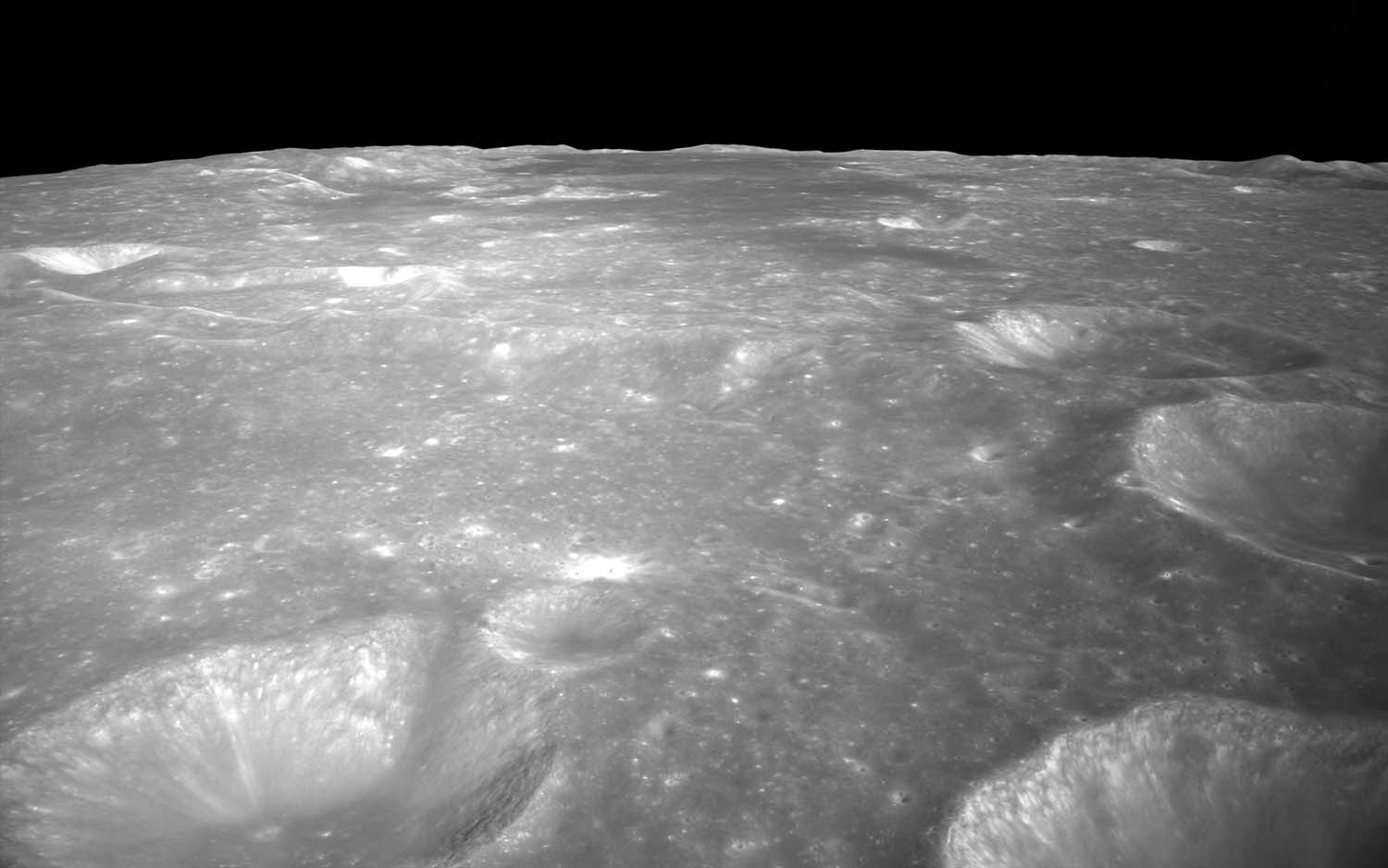

No one had previously attempted such a feat — and for good reason. The far side of the Moon offers unique challenges for human exploration due to its rugged terrain and lack of direct view from Earth.

Because the Moon rotates around its axis at the same rate as it orbits Earth, the far side of the Moon is always facing away from us. This makes communicating with spacecraft on the far side difficult, as radio signals are blocked.

In addition, it’s also far more difficult to land probes on the far side of the Moon given that its surface, which faces outward toward the rest of the Solar System, is pockmarked by significantly more impact craters than the Moon’s near side.

“Due to the protective effect of Earth, the side of the Moon that always faces Earth has experienced fewer (asteroid) impacts, while the far side has experienced more,” Hou Xiyun, a professor of astronomy and space science at Nanjing University, told domestic media.

These factors mean that scientists still have limited knowledge about the nature of the Moon’s far side. Before Chang’e-6, a total of 10 probes had previously collected samples from the lunar surface, but they had all been taken from the near side.

The soil samples from Chang’e-6 could therefore provide enormous value for researchers looking to understand the lunar ecosystem and how it has developed over time.

“Through comparative studies in the laboratory, we can effectively reveal the different evolutionary processes that took place on the near and far sides of the Moon,” said Hou.

The mission is also a vital stepping stone toward China sending — and eventually settling — astronauts to the Moon. Now that Chang’e-6 has retrieved samples from the far side, the goal is to send a Chang’e-7 mission to the Moon’s South Pole.

Chang’e-7 is designed to search the lunar South Pole for traces of ice — which is considered key to supporting a long-term presence on the Moon — and then work with Chang’e-8 to start work on building a lunar base.

How did the mission work?

Chang’e-6 had a similar design to Chang’e-5, with a spacecraft made up of four main modules: an orbiter that propels the craft to and from lunar orbit; a lander that descends to the lunar surface and conducts the sampling operations; an ascender attached to the lander, which blasts off from the lunar surface and reconnects with the orbiter; and a returner that descends back through the Earth’s atmosphere.

But landing on the far side of the Moon presented myriad new technical challenges — the greatest of which was the difficulty of communicating with ground control back on Earth.

“Landing the probe on the far side of the Moon is currently difficult to pull off as a fully autonomous process; it still requires the support of a telemetry and command system,” said Hou.

To solve this problem, China launched a satellite — Queqiao-2 — into lunar orbit back in March, which was used to relay communications from Earth around to the dark side of the Moon. This allowed ground control to keep track of Chang’e-6 and control its landing, sample collection, and ascent back into lunar orbit.

But even with the relay satellite, things were far from simple. The Moon still partially blocked signals at certain points in its orbit, meaning that Chang’e-6 had to complete its entire mission in just 14 hours — several hours less than its predecessor, Chang’e-5.

With Chang’e-6 needing to collect samples from several locations and depths on the far side of the Moon to provide scientists with a comprehensive picture of the environment, the ground control team faced a daunting challenge.

“While each individual task may not be overly difficult, compressing the same workload into a very short timeframe poses a significant challenge in itself,” Jin Shengyi, an expert from the China Aerospace Science and Technology Corporation, told state broadcaster station CCTV.

To speed things up, the team upgraded the technology used in the probe, allowing it to execute more tasks autonomously and making it less dependent on maintaining a stable communication channel with Earth.

“We have also used new techniques to speed up the operation of the mechanical arm and optimized the route taken by the lander to compress the time needed to complete the sampling,” Jin said.

Fortunately, the 53-day mission proceeded smoothly. Chang’e-6 launched on May 3 and touched down successfully on June 2 in an impact crater on the Moon’s far side known as the Apollo Basin.

The Apollo Basin is located inside the even larger South Pole-Aitken Basin — the oldest and largest impact crater on the Moon’s surface, with a surface area equivalent to around half of China. The Apollo Basin landing site was chosen because it’s flatter than most other areas in that region of the lunar surface.

After completing its sampling, Chang’e-6 rocketed back toward the Earth’s orbit at a speed of nearly 11.2 kilometers per second — 30 times the speed of sound — before the returner descended back through the atmosphere, deploying parachutes twice to ensure a safe landing.

The returner and its samples — which Chinese media have been jokingly referring to as “Moon specialty products” — will now be processed by ground crews in Inner Mongolia before being airlifted to Beijing.

Additional reporting: Li Dongxu.

(Header image: The Chang’e-6 returner module lands safely in the grasslands of China’s Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, June 25, 2024. Xinhua)