Chinese Women Are Sick of Dowries. Why Are They Still Common?

In China, it’s traditional for families to provide financial support when their children get married, with the groom’s parents usually expected to give money to the bride’s parents. Known as the “bride price,” it symbolizes the establishment of marriage as well as a form of compensation to the woman’s family for the loss of her labor. The woman’s parents will then typically give her gifts to take with her to her new family, which can be thought of as a kind of dowry.

These dowries often include various daily necessities the woman will need in her new life, as well as a small amount of cash or jewelry. The particular items, quantities, and values of dowries have varied across historical periods, regions, and social classes, and the question of who owns or can use the dowry is highly complex.

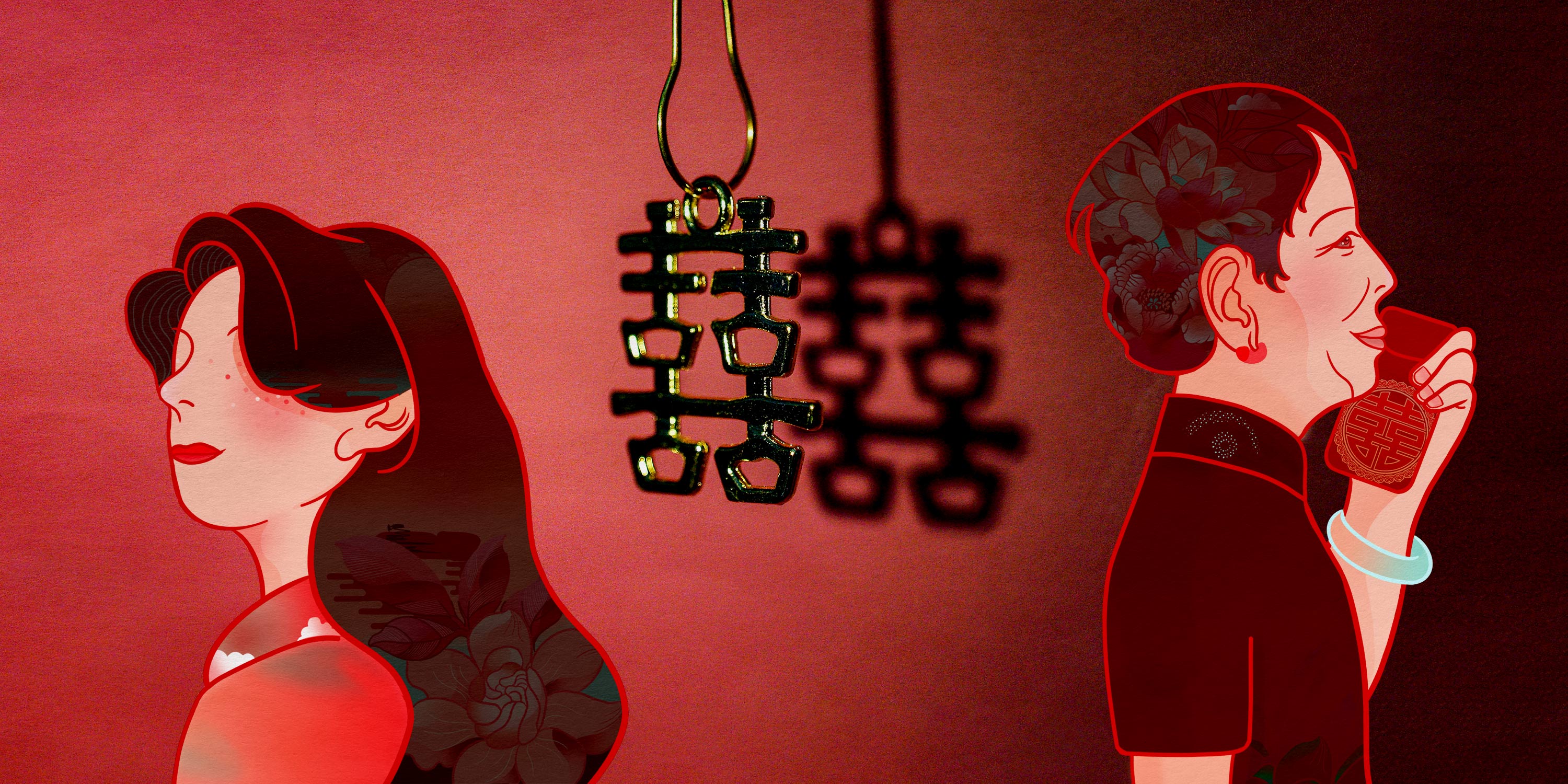

Although sometimes thought of as a feudal relic, dowries seem to have regained momentum in contemporary China, with parents preparing their daughter’s dowries months ahead of their weddings. These items are often purchased by the mother of the bride at special wedding supplies markets, and nowadays tend to be more symbolic than practical, with the idea being to display them on the wedding day. Most are bright red and feature the Chinese character for “double happiness,” as well as traditionally auspicious motifs such as Mandarin ducks, dragons, phoenixes, or the double-headed lotus. They are generally related to housework and reflect conventional ideas of women as housewives and caretakers; fertility symbols are also commonplace, such as a baby wash basin. Other items are specially prepared for dutiful daughters-in-law to gift their new in-laws, such as red cotton socks embroidered with the character for happiness.

Brides and their mothers are well aware of the traditional gender norms that these objects represent and reinforce. While young brides are therefore often resistant to the practice, their mothers insist that a complete dowry demonstrates traditional etiquette and a good upbringing, which can win favor with the man’s relatives and create a favorable image for the daughter among her in-laws.

However, it would be a mistake to see women’s parents as guardians of traditional gender norms or to assume that they believe their daughters should strictly adhere to the traditional responsibilities of wives, daughters-in-law, and mothers in their in-laws’ homes. In the course of my fieldwork, my research team and I interviewed 25 parents of married daughters. We found that they tended to see dowries merely as a practical concession to gender norms, rather than an endorsement of them.

“My daughter said that these things were too tacky and couldn’t be used in the future,” one interviewee explained. “She even asked me if I expected her to do housework every day after she was married. Of course I didn’t, but these are part of the festivities. Her in-laws and others would see them on the wedding day, and her elder sister had them all when she got married. If they’re not there, we’d lose face, right? Plus, it’s not like I expect her to carry these things around her in-laws’ house every day, serving them. She can just put them away when the wedding is over.”

Interestingly, contemporary dowry lists don’t just feature the traditional items mentioned above: The woman’s parents will also give her real money. Traditionally, except for a few wealthy families, the bride’s family was not expected to provide financial support to the young couple. That has changed in recent years, however, and almost all middle-class parents we interviewed reported buying large amounts of gold jewelry as part of their daughters’ dowry.

Sometimes, the value of these gifts can exceed that of the bride price paid by the groom’s family; one frequently mentioned estimate was that the dowry should be worth double the bride price. Such significant financial assistance and transfers of property not only represent a substantial form of support by parents for their daughter’s future life, but also indicate their wish for their daughter to be financially independent of her in-laws, and for her to have more autonomy and greater sway in their marriage.

One interviewee, whom I’ll call Wenjing, reported having mixed feelings about the idea of her daughter, then a Ph.D. student, tying the knot. Although she was pleased that her daughter had finally found a life partner, she worried that she might be pressured by her husband’s family to have a child before she’d finished her Ph.D., thereby delaying her studies. So Wenjing decided to give her a dowry that was double the groom’s bride price to improve her daughter’s future status and give her more of a voice in reproductive decisions. “My daughter doesn’t have a source of income while she’s studying,” Wenjing said. “If her fiancé gives a large bride price, they might make various demands on her or even pressure her into having children while she’s still studying. It’s taken a lot of work to study for a Ph.D., but we still hope that she can develop personally and have her own career. Until she’s done that, all we can do is give her a bigger dowry so that she can stand up straight in front of her in-laws.”

It’s worth mentioning that the bride’s mother often plays a primary role in the intense financial and emotional process of preparing the dowry. Not only does she undertake most of the necessary tasks, such as handling and preparing the items, but must also communicate with her daughter and help her adjust to the idea of married life. These mothers are naturally able to empathize with their daughters’ situations — and they will sometimes even challenge traditional patriarchal norms for the benefit of their daughters’ interests.

In preparation for their daughter’s wedding, an interviewee, whom I’ll call Aiyun, and her husband agreed that their daughter’s dowry should equal her bride price. However, Aiyun’s husband and father-in-law later demanded that they be allowed to temporarily hold onto half of the dowry and bride price and put into the family business, a condition that was approved by Aiyun’s daughter’s prospective in-laws. But Aiyun had no patience for their maneuvering. “I don’t expect you to part with the money happily, but as a father, you surely won’t take our child’s money?” she recalled saying. “When our eldest son got married, you happily bought the wedding apartment and paid the bride price. I never saw your face change. But now it’s your daughter getting married, you’re ruthless!”

Aiyun then gave her daughter all of her bride price, plus the gold and jewelry Aiyun had accumulated over the years. Indeed, the mother’s main role in preparing the dowry and protecting her daughter’s interests creates the conditions for greater mother-daughter unity. This strong gender unity is a core driving factor underlying the transition of the Chinese family from a traditional patriarchal, patrilineal system to a more bilateral one.

(Header image: Visuals from VCG, reedited by Sixth Tone)