The ‘Santi’ Aren’t Real

For as long as I’d been waiting for Netflix’s new “3 Body Problem” series, an adaptation of what is perhaps contemporary China’s most popular work of fiction, I didn’t exactly go into the first episode with much hope. My friends and I planned a marathon watch party, but it was the kind where you take a shot after every mistake or bad adaptation decision.

To my surprise, the experience — embellished with New Haven’s famous Apizza — was quite pleasant. The show hit its marks: It was quick-paced, clearly told, and visually engaging enough to keep us hooked, despite most of us having read the books. By midnight, we’d watched all eight episodes and had barely touched our drinks.

Except for at one moment: Seven minutes into episode six, Thomas Wade, the merciless leader of the Planetary Defense Council played by Liam Cunningham, announces the extraplanetary threat faced by Earth. “The Santi are real!” he declares.

“They mean Santiren,” a friend muttered.

Santi means “three bodies.” It is the name author Liu Cixin gave to a fictional planet in the Alpha Centauri system with three suns orbiting each other in random order, generating endless chaos and extreme weather. In Chinese, adding ren, or “person,” would give you “people from Santi.” Without it, what we have is only a planet, a cosmic phenomenon, or a punchy two-syllable catchphrase better suited to the pronunciation habits of Earth’s English-speaking viewers, but not an entire sentient alien race.

One of Ken Liu’s signature inventions when he translated Liu’s “Three-Body” trilogy into English was the word Trisolaris — “the planet of three suns.” Santiren thus became Trisolaran, or the people of the planet of three suns. Not long ago, Chinese readers were celebrating how eloquently this term was translated. Now, I feel like I’m supposed to be happy that a translation is no longer needed. “The santi are real” seems to signal the acceptance of a Chinese term by Netflix’s Anglophone audience: the Chinese term santi, its original form, is thus made “real” in the Anglophone world. But somehow the term rings utterly hollow after being uprooted from its linguistic context. Instead of giving me a sense of familiarity or even pride, santi sounds more foreign and detached than Trisolaran. For once, I find myself appreciating the translation over the original.

Translation is a difficult and oftentimes underappreciated work. I frequently get asked about the most difficult aspect of translating Chinese sci-fi into English. “It’s probably the bits that describe hard science, right?” people will ask.

My answer is always no. The science is the easy part. The translation of modern European scientific terminology into Chinese was carried out methodologically a century ago as part of the New Culture Movement. It went hand in hand with the development of the modern Chinese language itself. There weren’t direct equivalences for subjects like “physics” and “chemistry” or terms like “particle” or “quantum” in classical Chinese; everything needed to be defined, explained, and named. The Chinese intellectuals who learned and spread the knowledge of Western science via translation essentially reinvented the Chinese language. As a result, almost every science term that I have ever had to translate into English already has a specific corresponding word at hand. I only need to translate back what had already been translated into Chinese a century ago.

It’s the culture that’s difficult: myths and philosophies that have been around since ancient times; nuances hidden in words that could only be deciphered with the help of context, much of it tucked between the lines; and the ever-changing zeitgeist of contemporary China.

Take the word laoshi, for example. Characters in Liu’s “The Three-Body Problem” trilogy often refer to the brilliant astrophysicist Ye Wenjie as laoshi, but not always for the same reason. “Teacher” would be the most obvious translation of the word, a near-perfect English equivalent. However, when I address someone as laoshi, it’s almost always more complex than simply acknowledging that this person has at one time taught me something. It’s an honorific that encompasses a range of meanings, going from extreme reverence to basic politeness or perhaps just an acknowledgment that someone is an intellectual. In other cases, it can also be an expression of endearment, an indication of a connection as deep as a blood tie: The Confucian classics teach disciples to honor and love their laoshi the same way they honor and love their father.

For words like laoshi that come loaded with so much cultural context and social subtlety, some translators avoid the process of translation altogether, dropping Chinese words into the text, with the readers left to figure out what they mean from context. They are often italicized to emphasize their “foreign” nature, not unlike how I had to italicize all of the pinyin in this article to comply with Sixth Tone’s style guide. Other Chinese-to-English translators and Chinese diaspora writers working in English have sought to de-italicize Chinese terminology, as a means to demonstrate that English, a language spoken by people all over the world, should embrace diversity and stop treating borrowed words as inherently foreign.

However, in a cultural context in which Chinese is still treated as a peripheral language, the line demarcating representation from appropriation is always going to be blurry. Harking back to the case of Netflix’s “3 Body Problem,” was the decision to keep the word santi a well-meaning tribute to the original Chinese books? Or was it merely a way to add a dash of exoticism? The story is now set in Britain featuring a predominantly non-Chinese cast, so why do the invasive aliens have a Chinese name?

As a translator, I can’t help but examine this issue from the perspective of translation. After all, the question “What’s the most difficult aspect of translating Chinese sci-fi into English?” goes not only for literature, but for media adaptations, too.

My answer after watching Netflix’s “3 Body Problem” remains the same: It’s never the science that’s hard to translate. My friends at the watch party come from vastly different backgrounds, but they could all appreciate the universe of the show. Liu’s trilogy is primarily constructed out of the lexicon and tropes of science fiction, a genre built upon modern science as well as rather Eurocentric concerns for capitalism, resource acquisition, and territorial expansion. If anything, positioning Liu Cixin within Chinese literary history is more difficult than comparing him to his English-language predecessors such as Arthur C. Clarke and Isaac Asimov. As a work that fluently speaks the poetic and metaphorical language of Anglophone sci-fi, “The Three-Body Problem” trilogy is highly translatable. If we view it as a work of sci-fi before we see it as a work of Chinese sci-fi, then there is no reason a Hollywood adaptation wouldn’t be a hit.

At the same time, the discomfort and dissociation I felt upon hearing the word santi appear in the show indicates that culturally sensitive translation remains more difficult than it looks. Chinese audiences are no longer satisfied with a mere hand-waving away of authenticity concerns, not when we know how much more there is of Chinese culture that can be excavated, reimagined, and brought to the world’s stage.

Editor: Cai Yineng.

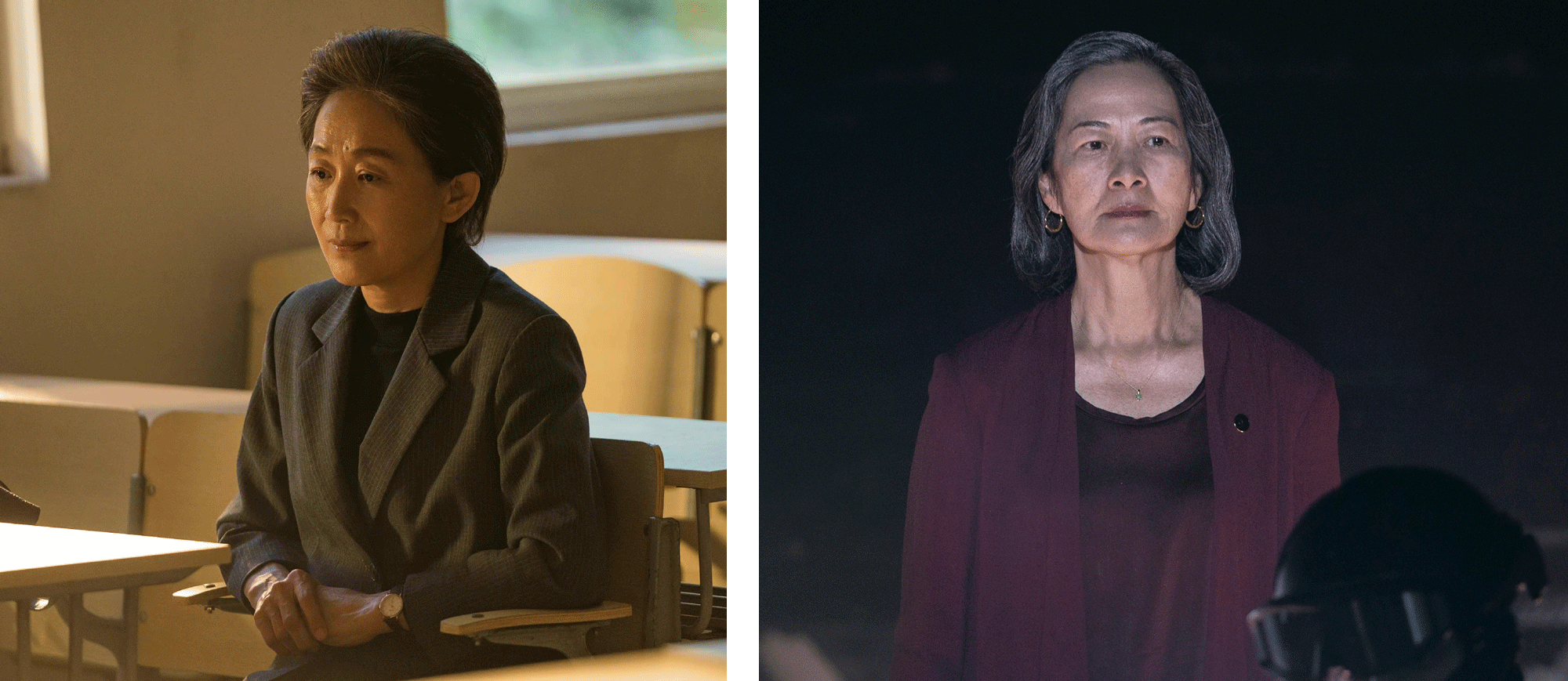

(Header image: A still from Netflix’s “3 Body Problem” series. From Douban)