Steering Through Shanghai: A Taxi Driver’s Perspective

Editor’s note: Within the pages of “My Experience Driving a Taxi in Shanghai,” recently published by Guangdong People’s Publishing House, Hei Tao, pen name of Li Enjie, uses his own lived experience and perspective as a taxi driver in Shanghai to describe stories from inside the industry. This book, similar to nonfiction works “Beijing Courier” and “My Mother, Cleaning Up,” provides a grassroots snapshot of working life.

Li has a diverse work background: After majoring in fine arts, he worked as an editor before returning to his small hometown to open a powdered milk shop. In 2019, at 35 years old, he chose to “drift around Shanghai,” moving to the metropolitan city to work as a taxi driver.

As a witness to snippets of his diverse riders’ lives, the stories found in “My Experience Driving a Taxi in Shanghai” stitch together another face of the sprawling metropolis. The following is an excerpt.

I once heard a story from Japan. One day, a taxi driver met a middle-aged male passenger. After getting in the car, the passenger pointed to the Porsche in front of them and asked, “Isn’t that car beautiful?”

The taxi driver said, “That goes without saying. Porsches are obviously beautiful!” Looking extremely pleased, the passenger then said, “That’s my car!”

The driver responded with confusion, “If it’s your car, then why aren’t you driving it?”

The passenger said, “Are you stupid or what! If I were driving it, how would I be able to appreciate its beauty?”

This passenger was, in fact, the famous actor Kitano Takeshi. As it turned out, Takeshi, in all his fame and riches, had purchased the newest model of Porsche but had become saddened by his inability to see himself proudly driving the car. Only then did he think of having a friend drive his car while he took a taxi; this way, he could see his elegant Porsche.

In my career as a taxi driver, I haven’t encountered any arrogant, out-of-touch passengers like Takeshi, but I have run into many interesting passengers. They tell stories, some peaceful and light yet profound, and some so complicated they lead you to ask yourself in astonishment if it’s taxi driving that allows you to meet such interesting people.

The most famous taxi driver is actually a fictional character — Travis from the film “Taxi Driver.” He’s a Vietnam War veteran who drives a taxi to earn a living and calm his PTSD-afflicted soul. Despite moving through the bustling and vivacious streets of New York City each day, he finds it gaudy and doesn’t fit in. The cold and dreary atmosphere created by the film, as well as the feelings of estrangement between man and society therein, left a profound impression on me.

I feel that Shanghai is China’s New York City. If one day I could drive a taxi and shuttle back and forth through the glittering lights and the mountains of buildings and sea of roads, wouldn’t that be amazing!

Through happenstance, I unwittingly had the opportunity to do so and became a “street flâneur,” steering wheel in hand.

For the previous 35 years of my life, I had only lived in northern China and had never been to Shanghai before. This city filled with skyscrapers and stories was relegated to my limited imagination and limitless yearning. I knew that one day I would come to Shanghai, and to meet it by chance, to get to know it through working as a taxi driver was undoubtedly the best thing.

Here, among old Shanghai natives, taxi drivers are called chatou drivers, derived from the English word “charter,” meaning “to rent” or “to hire,” and belonging to standard Chinese Pidgin English.

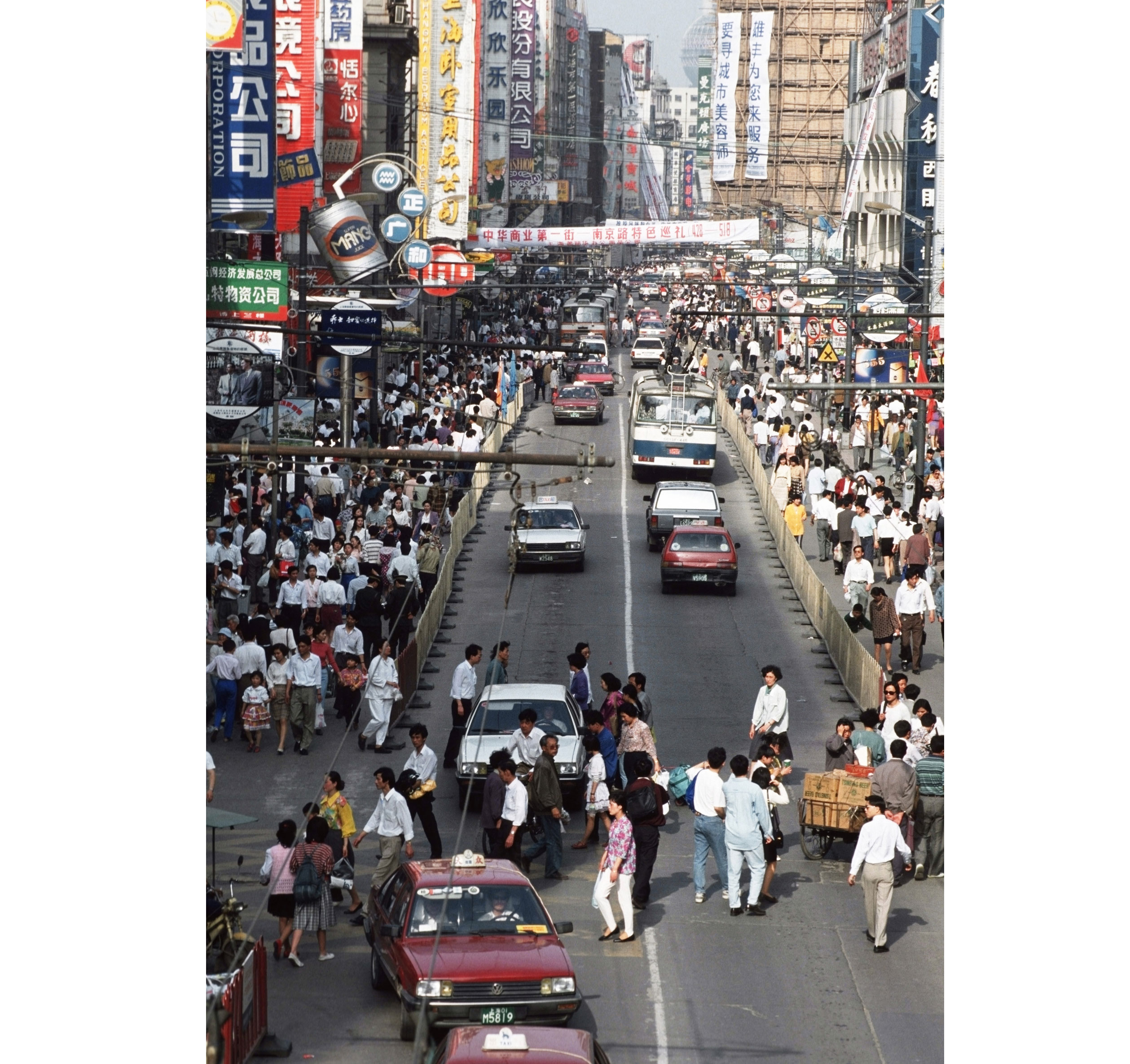

Yangjing Bang, a creek that later lent its name as shorthand for Chinese Pidgin English, once flowed through Shanghai. Now filled and paved, it forms today’s Yan’an East Road. In its heyday, Yangjing Bang marked the boundary of the foreign settlements, with thriving businesses on both sides. To conduct business with Westerners, Chinese merchants began to learn foreign languages, giving birth to a unique linguistic hybrid.

This pidgin language was simple yet ingenious, built on a Chinese foundation with liberal borrowings from English. It spawned phrases like “no can do,” “lose face,” “long time no see,” “people mountain people sea,” and “one piece how much.” It also contained some mixed transliterations from Chinese, as when describing a car accident: “One car come, one car go, two car peng peng, people die!” (Two cars are moving towards each other, they collide, slam! Everyone dies!). Yangjing Bang English was mainly used colloquially, and most expressions have faded into history. Some of its transliterations, however, still are alive and well.

A century ago, Shanghai’s taxi drivers were rickshaw pullers — a fairly good way to earn a living. Twenty to 30 years ago, when taxis were first rapidly developing, taxi drivers earned high wages, and could even be considered the “gold-collar workers” of their time, highly sought after as marriage prospects. Even a decade ago, taxi license plates in major cities could easily fetch upwards of a million yuan.

But times are changing. The rise of ride-hailing apps has now eaten into traditional taxi services. While early entrants to the profession in Shanghai can typically afford two to three apartments before they retire, fewer young people now view taxi driving as an attractive career or are willing to do this kind of work. Taxi companies can only recruit drivers from suburban Chongming Island. Yet even this pool of drivers is dwindling, forcing companies to loosen the restrictions for drivers about where their registered residence is. This allows for people like myself to enter the profession.

Today, Shanghai has about 40,000 taxis and more than 70,000 taxi drivers, completing over 400 million trips annually. The cumulative distance traveled exceeds 5 billion kilometers — enough to circle the Earth 120,000 times. I have friends who ask me, “In this era of ubiquitous ride-hailing apps, what are you doing driving a taxi?” I responded, “Is there any difference?”

The evolution of ride-hailing apps in China differs from other countries, but the differences between these services and traditional taxis are blurring. Ride-hailing companies have gradually included rental cars and outsourced drivers, while taxis increasingly rely on booking platforms. The result is a blurring border between the two.

If we look at Europe and America or China, in the past few years, the taxi industry in all those regions has been impacted by ride-hailing apps, with profits dropping dramatically. However, China’s market has stabilized after a series of restructuring and reforms. The end of the ride-hailing apps’ price war saw speculative drivers exit the market, and taxi drivers’ profits rebounded to 70-80% of previous levels.

Taxi driving is certainly not as lucrative as it was in the past, and this is common knowledge. However, to make a living, drivers still flood the roads. If someone leaves, others are eager to take their place.

What are taxi drivers most criticized for? Of course, it’s when they refuse passengers, take detours, become picky with their passengers, and employ dubious pricing tactics. Certainly, as all quick methods of making money are essentially written in the Criminal Law of the PRC, these behaviors, which frustrate passengers, have long been addressed in professional standards and regulations.

Once, I heard a female passenger say to her friend, “You know why I never use ride-hailing services?” Her friend gave a few reasons, but she rejected all of them, finally saying, “Most cars on the apps are electric nowadays. With all those batteries, there’s too much radiation!” I can understand this kind of misgiving, but her statement actually has no real basis. Scientific tests prove that the daily electromagnetic radiation we’re exposed to is far from the level that would do harm to our bodies.

People find fault with both taxis and ride-hailing apps. Some taxi drivers reject customers, while some ride-hailing drivers take detours. Most of the time, a driver’s performance rarely depends on their affiliation or industry regulations. Rather, it stems from their personal ethics, and what’s more important is whether the companies implement effective discipline, supervision, and accountability measures.

My work philosophy is simple: Follow your own professional values, strive for skill and dedication in your work, and appreciate the happiness and interest you get in the process. I’m comfortable with my professional ethics, and my skills are improving over time. But how do I take joy in my work?

I really enjoy driving, and although I’ve not done any research on the subject, there’s an undeniable pleasure in being on the road. When I first began driving a taxi in Shanghai, I didn’t know the roads well, and my phone navigation became an indispensable tool for me and many new drivers — this is a convenience afforded to people by the development of technology. Of course, navigation is just a tool, and you must develop an intuitive feel for the city’s layout. After you become acquainted with the roads, you have a clear map in your mind, allowing you to use navigation as a supplement rather than a crutch.

As I grew familiar with Shanghai, I felt calm and confident, and I became engaged and active. Unlike Travis from “Taxi Driver,” I don’t feel estranged from the bright lights and liveliness of the city. After all, Shanghai isn’t the New York of that era, and I don’t have any deep-seated trauma. Instead, I feel more like Granny Liu paying a visit to Grand View Garden in the book “Dream of the Red Chamber,” where everything and everyone seems interesting and new. Although sometimes I meet frustrating people, that’s part of life. The city’s efficiency and sophistication are alluring, and one must accept its flaws and the less desirable aspects.

Life’s most intriguing moments are found in the space between certainty and uncertainty. The certainty: Today, I will drive my taxi, visit a few places, and meet 20-30 passengers. The uncertainty: The specific places I’ll go and the kind of people I’ll encounter. It’s like opening a mystery box or starting a book you’ve never read before — there is so much to look forward to.

This article, translated by Marianne Gunnarsson, is an excerpt from the book “My Experience Driving a Taxi in Shanghai” by Hei Tao, published by Guangdong People’s Publishing House in March 2024. It is republished here with permission.

Editors: Xue Ni and Elise Mak.

(Header image: A promotional photo for the book “My Experience Driving a Taxi in Shanghai.” From @绳子的书与微观世界 on Weibo)