The Chinese Painter Who Fused East and West

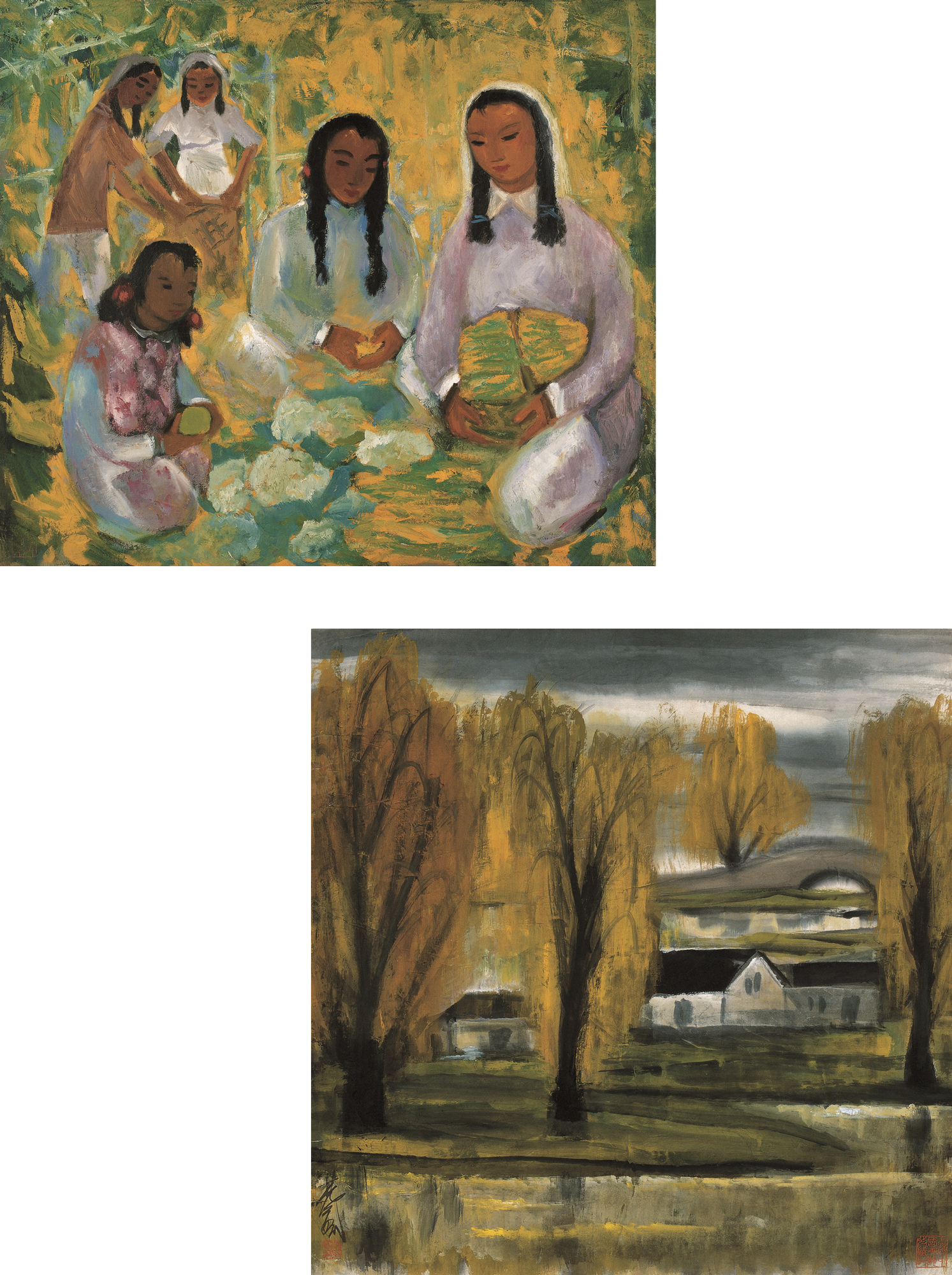

The village homes sit partially obscured, their white walls and black roofs standing out amid the oranges and greens of the grove. The hazy reflection of the sunlight off the foliage creates a translucent texture reminiscent of the Impressionists’ approach to light and shadow, yet the stillness of the colors and the lines is altogether Eastern in its charm.

Titled “Autumn Haze” and dated 1950, the painting is the work of Lin Fengmian, one of the masters of 20th century art. Featured alongside other works by Lin and his student Wu Guanzhong as part of a recent special exhibition at the China Art Museum in Shanghai, it seemed to pose a question: Is it possible to redefine what makes a painting, especially a landscape painting, “Chinese”?

To Lin, who was born in 1900, the answer lay neither in looking back at traditional landscape paintings nor in the wholesale acceptance of Western art but, rather, in the fusion of East and West. In a collection of essays on art, Lin offered this comparison of Chinese and Western art: Western landscape paintings depict the object, focusing on realism and imitating nature, whereas Eastern art recreates impressions, offers more expressiveness, and depicts the imaginative. Lin believed that Chinese art should absorb the forms of expression found in Western art but reconcile it with the emotional needs of Eastern art.

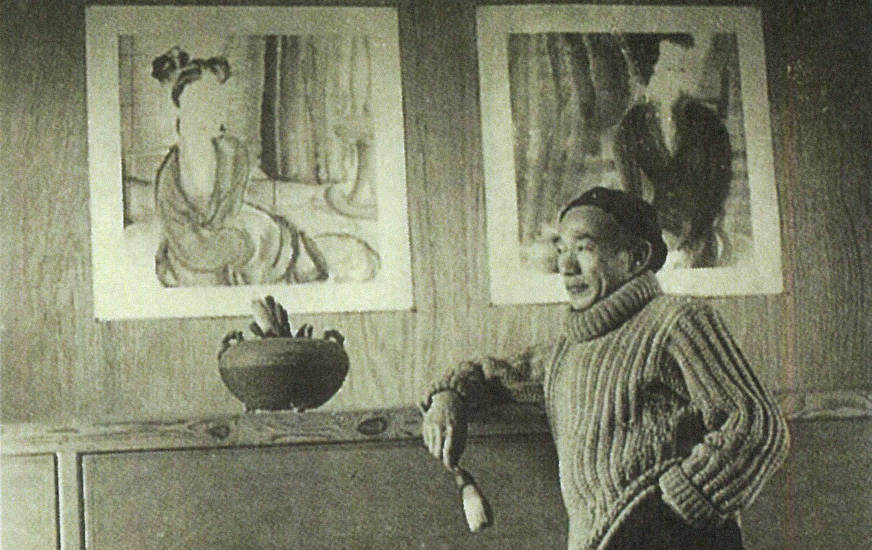

Lin’s artistic career began in the southern city of Meizhou, where he learned to paint by copying works from the “Manual of the Mustard Seed Garden,” which for three centuries had been a required text for Chinese children studying art. Having grown dissatisfied with these highly procedural drawings by his adolescent years, Lin eventually embraced the novel world of art he discovered in Western picture cards sent from abroad.

Amid the wave of political and cultural modernization that swept China in the 1910s, Chinese artists were beginning to learn from Western painting, though most still adhered to traditional styles. In 1919, Lin learned of a work-study opportunity in France and immediately set about raising the necessary funds.

Upon reaching the art academies and studios of Europe, Lin devoted himself to practicing everything he could not learn in China, focusing on sketching and realistic aesthetics. However, he quickly realized that Western art itself was in turmoil: the naturalism and realism he had so earnestly studied were precisely what the Symbolist writers and artists of the 1920s were trying to subvert. With encouragement from his teacher, the artist Ovide Yencesse, Lin spent time studying the Asian works on display at European museums, absorbing influences from Chinese porcelain and the portrait bricks of the Han (202 B.C.–220 A.D.) and Tang (618–907) dynasties.

Contemporary Western artists had been incorporating elements of Eastern art from the very beginning, such as bianjiao, or “corner,” composition, and an emphasis on lines, distorted forms, and contrasting colors. Impressionist master Claude Monet and Cubist master Pablo Picasso both painted Eastern-styled ladies in kimonos clutching folding fans in “La Japonaise” and “Women of Algiers,” respectively, while Vincent van Gogh copied paintings of plum blossoms. Unlike earlier Europeans who collected ancient Chinese art out of Orientalist curiosity or as colonial trophies, the references to Eastern art found in contemporary styles like Impressionism, Post-Impressionism, Fauvism, and Cubism stemmed from a genuine mix of modernist aesthetics and Eastern philosophical thinking.

This discovery compelled Lin to merge Chinese painting traditions with new styles of Western art as a way to counter the increasing rigidity of Chinese painting. The problem, he believed, was not in the technique itself. It was the growing detachment from nature that arose from an overemphasis on the aesthetics of ink and brushwork up through the Ming (1368–1644) and Qing (1644–1911) dynasties, which he believed produced formulaic work that stifled creativity, as when he was a child copying from “Manual of the Mustard Seed Garden.”

“Art is a direct expression of the painter’s thoughts and feelings,” Lin wrote in 1933. “Though his thoughts and feelings may belong to him, he himself is of the times, so the changes of the times should directly affect the content and the technique of the art of painting. If those never change and the painter only ever follows the artists of past millennia, then one might say that their art no longer expresses the painter’s thoughts and feelings!”

On art education, Lin — who returned to China in 1926 to teach — argued that “basic art training should take nature as its subject and apply scientific methods to correctly reproduce objects as the basis for creation.” To that end, he asked his students to be among nature and draw there, rather than copy works from books. Such practice was meant not to force them to make naturalistic art but to allow artists unrestrained creativity as they sought to grasp the essence of things.

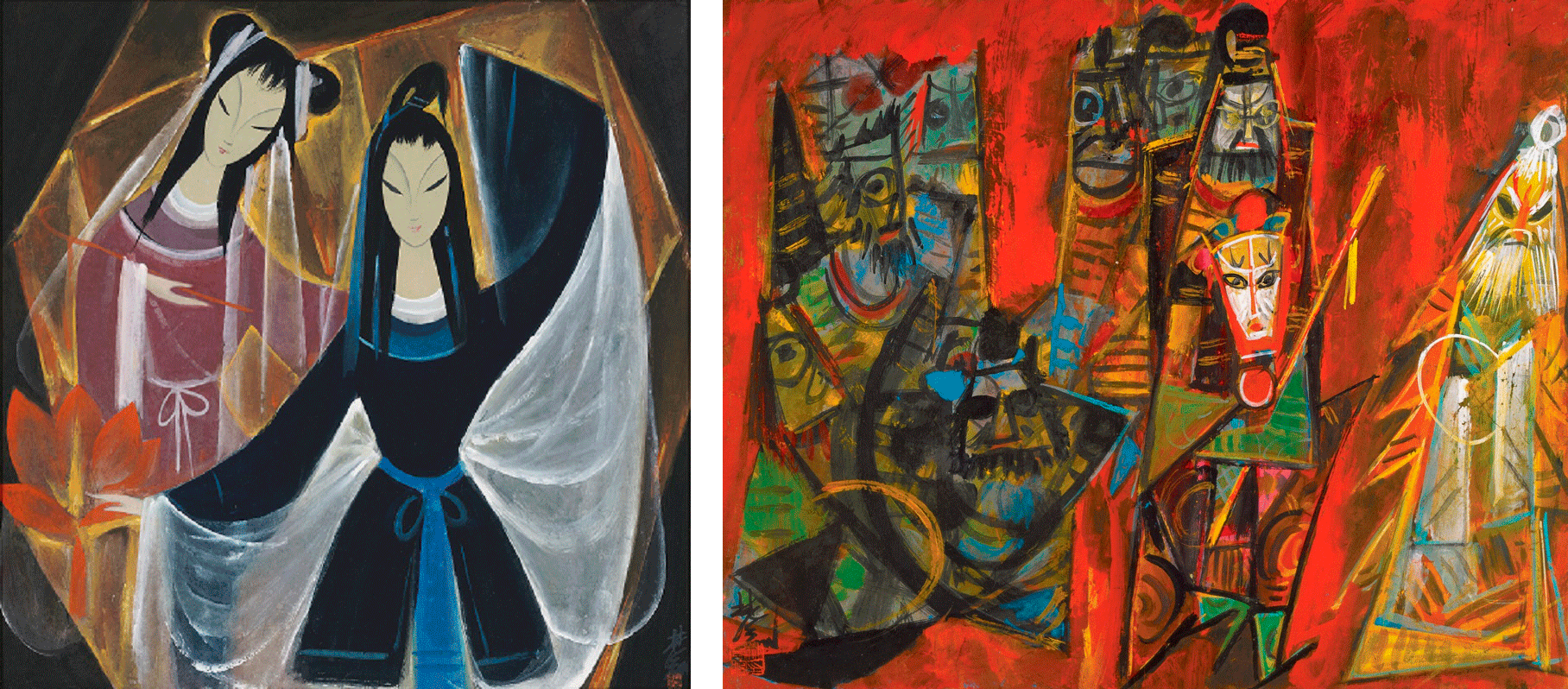

Lin’s own artistic philosophy was unique. In favor of Western approaches, he abandoned the rigidity of the art academy for the new traditions of Romanticism and Cubism. For Eastern influences, he absorbed early traditions and folk art — predominantly Han and Tang art — in place of the brush-and-ink method of literati painting that came later. In the 1930s he developed an interest in the floral motifs on porcelain, stone reliefs, lacquerware, and the style of shadow puppets, writing that he enjoyed their “simplicity and candidness.”

The War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression tested the limits of Lin’s artistic exploration. The limited amount of gouache, ink, and rice paper he had for painting while living alone in the wartime capital of Chongqing after 1939 ultimately led to a refreshing style that merged Eastern and Western perspectives. This is evident in his portrait work during the 1940s, in which the large blocks of red and green, randomly placed, create a heightened mood. Additionally, the chaotic superimposition of black lines, coupled with a collage of shapes, foreshadow Lin’s in-depth study of Picasso’s Cubism in the 1950s. In these works, Western modernism is commingled with the costume aesthetics of Chinese opera figures.

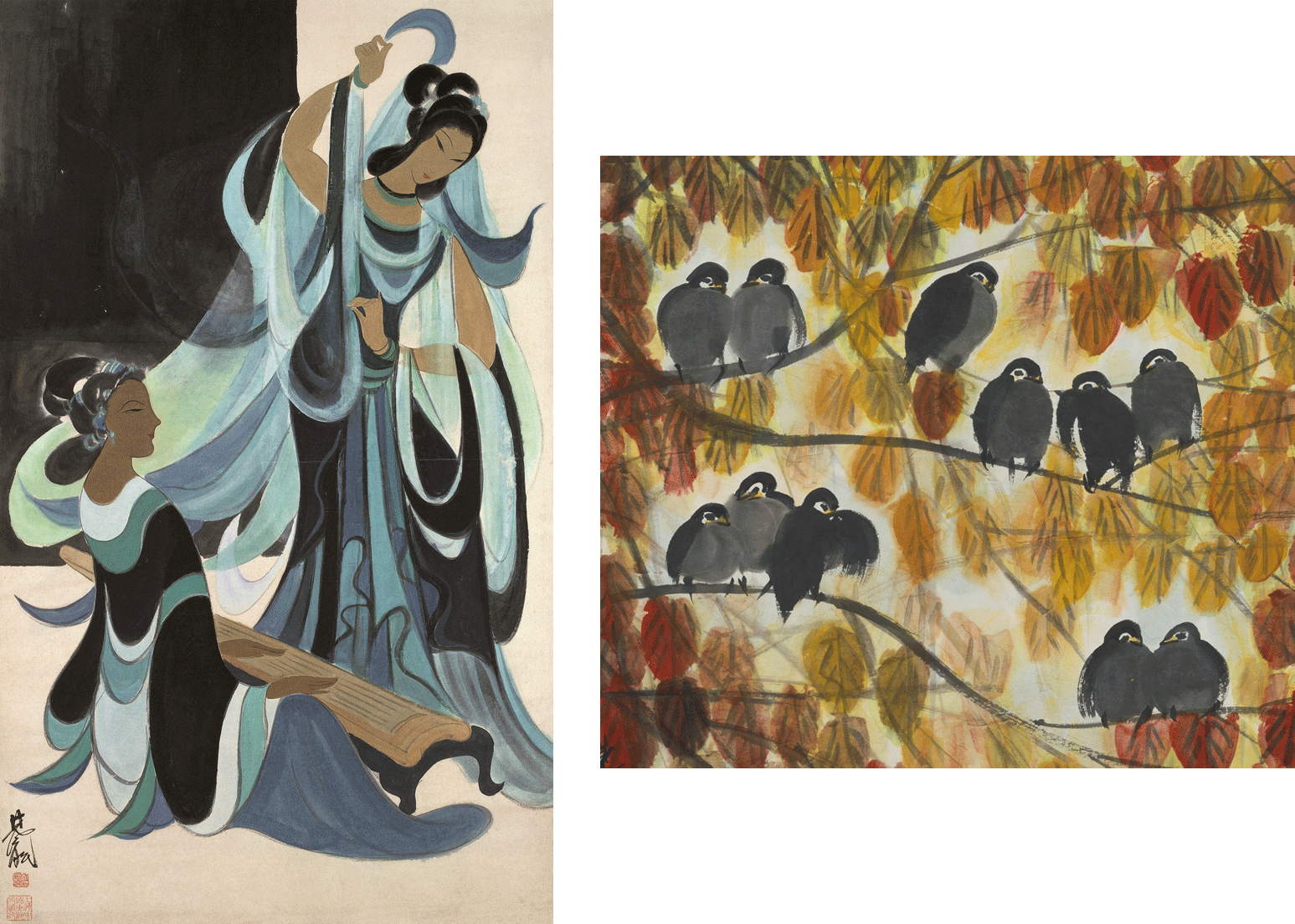

Lin’s approach would mature in the 1950s and 1960s. For instance, the gigaku — Japanese masked dancers — that he painted in the late 1950s have oval faces and simple features that bear a striking resemblance to work by Amedeo Modigliani, an Italian painter popular in the 1920s, while the smooth curves of the dancers’ bodies and the transparent textures of their attire nod to the charm of the early medieval murals found in northwestern China’s Dunhuang, along the Silk Road. Another example is his 1960s piece “Birds and Autumn Leaves,” in which the rounded blocks of color that form the birds share similarities with the geometric shapes used by Western Modernists.

These works forced me to reconsider the distinction between Eastern and Western art. The synergy of the two — as evidenced by Van Gogh, Picasso, and other Modernist masters’ appropriation of Eastern elements and by Lin’s efforts to fuse Chinese art with Western styles — actually began over a thousand years ago, in the caves of Dunhuang. So when Lin nods to the Dunhuang feitian (flying apsaras) in his paintings, it is difficult to say whether he was imitating ancient Chinese or modern Western art.

Lin himself offered a thorough deconstruction of the “East-West” concept in a 1936 article titled “My Interests.” “Among the arts, painting is merely a visual art expressed through colors and lines,” he writes. “Given that idea, ordinary ‘Chinese’ and ‘Western’ works are not altogether dissimilar.”

Lin continued to practice this belief decades later in Hong Kong, where he spent the last years of his life. Take “Bird Flying Over Pond,” which depicts classic themes of Chinese painting, for example. Although the viewer may not be able to immediately distinguish between the “Chinese” and “Western” styles in either piece, the inner clarity of the artist is crystal clear. “I hope I am always able to express my feelings with my paintbrush and with sincerity,” Lin once said about his later work.

Lin may lack the global recognition of some of his peers, but two of his students, Zao Wou-ki and Wu Guanzhong, likewise studied in France and revolutionized Chinese painting, albeit while balancing the characteristics of Chinese and Western art in different ways. For Lin, it was through unifying Chinese lines with Western colors; for Wu, it was through blending the “artistic moods” of Eastern and Western aesthetics; and for Zao, it was through seeking abstraction from ancient characters, calligraphy, and Song paintings. In the end, each of them created their own “Chinese landscape.”

Translator: Katherine Tse.

(Header image: “Lady in Pink With a White Lotus,” by Lin Fengmian, 1960s. Courtesy of the China Art Museum)