Stitching Masculinity: The Tailor’s Son Who Defied Gender Norms

Wang Xinyuan remembers spending his childhood in his family’s tailor shop in Jiujiang in the eastern Jiangxi province, listening to the rhythmic beat of his mother’s sewing machine day after day. Now 42, Wang has become a master in embroidery himself after realizing and fully embracing his talent.

By age 10, he had mastered basic tailoring skills: nailing buttons, hemming trousers, and ironing clothes, and becoming an invaluable helper to his family. Noticing his interest in embroidery, his aunt was the first to teach him how to embroider, stitching flowers and cats together.

To Wang, sewing was a basic life skill, as natural as breathing. However, when he left for boarding school in his teens, his abilities — which came in especially handy for fixing his torn sports kit — were considered unusual by his peers.

One day, a classmate caught Wang practicing embroidery in their dorm room. Surprised, his peer called him a “sissy,” a label that quickly spread among fellow students. Sensitive to the ridicule at that time, Wang took the sewing kit home with embarrassment, never to bring it back to school again.

From ‘sissy’ to ‘manly’

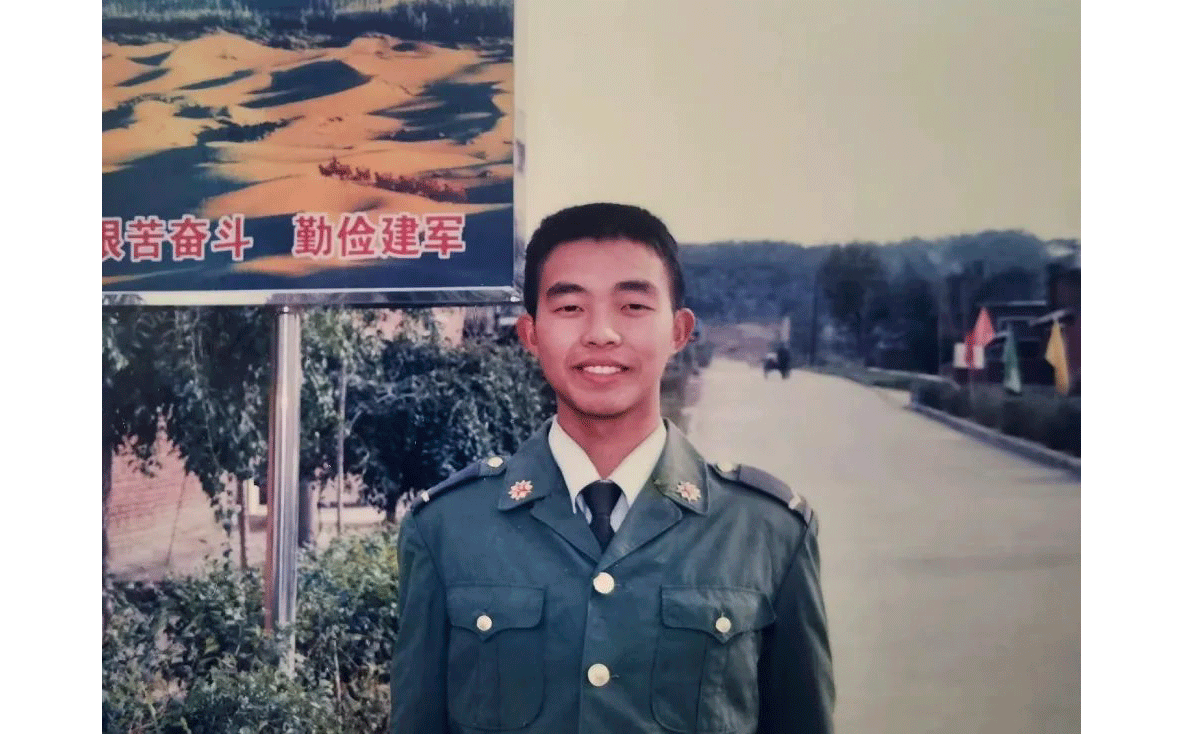

Being considered unmanly weighed heavily on Wang and made him self-conscious. Determined to prove his masculinity, he made a drastic decision to join the army after high school.

Wang went even further by choosing to be a soldier in the farthest reaches of the country, acting rashly out of a feeling of injustice, he said. A six-day train journey carried him to the country’s northwestern border, where he found his masculinity by becoming a member of the Air Force’s anti-aircraft brigade in Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region.

Trading needle for gun, Wang endured grueling, day-after-day training in the barracks, testing his resilience. He stood at attention for two hours at a time, his two hands clasped tightly against his trouser seams. In sub-zero temperatures, at times minus 30 degrees Celsius, he and other soldiers had to trudge through waist-deep snow during field exercises.

Wang recalled one particularly brutal night: from 1 a.m. to dawn, he ran endlessly through snow-covered roads. Upon returning to the camp, his coat was so frozen that it could stand upright on its own.

Reflecting on his military years, Wang felt a mix of pain and pride. “In the army, I didn’t have to prove my masculinity, as the uniform spoke for itself,” he said. “It is said that you may regret being a soldier for two years, but not being one for a lifetime. The training was really tough, but I’m proud that I persevered.”

Getting into embroidery

In 2001, Wang retired from the military, spending only two days in his Jiangxi hometown before venturing to Guangzhou, a metropolis in southern China, with a mere 200 yuan ($28) in his pocket. Seeking business opportunities in this economic powerhouse, he started as a security guard earning 400 yuan a month, and climbed the ranks to team leader and supervisor. However, he viewed this as a job only, not a career.

A chance visit to the Guangdong Folk Arts Museum in the city reignited Wang’s passion for embroidery. An embroidered portrait captivated him with its delicate expressions and masterful use of light and shadow, evoking memories of his childhood sewing machine’s hum.

After discovering that renowned Cantonese embroidery artist Wu Yuzhen created the piece, Wang decided to enroll at the Institute of Cantonese Embroidery in Foshan, in the southern Guangdong province, where Wu used to teach.

At the institute, Wang found himself the sole male among female embroiderers, stirring uncomfortable memories of his school days. However, conversations with the teachers there eased his concerns, and he decided to stay and learn embroidery from them.

Wang discovered that, contrary to popular belief, Cantonese embroidery had traditionally been a male-dominated craft since the Qing dynasty (1644–1911). Skills were passed on to men only as their patience and stamina were favored. Women only joined embroidery later as overseas demand increased.

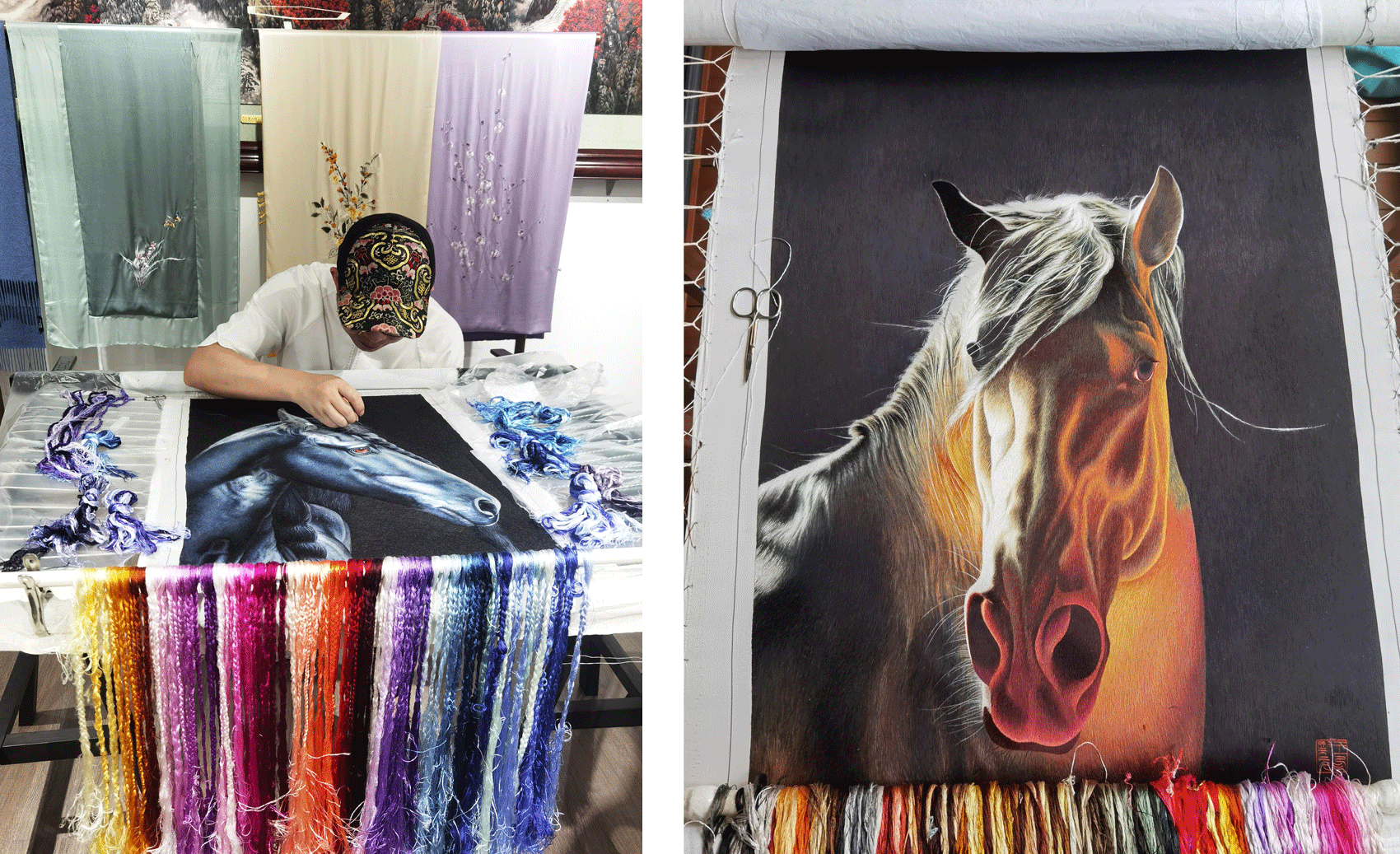

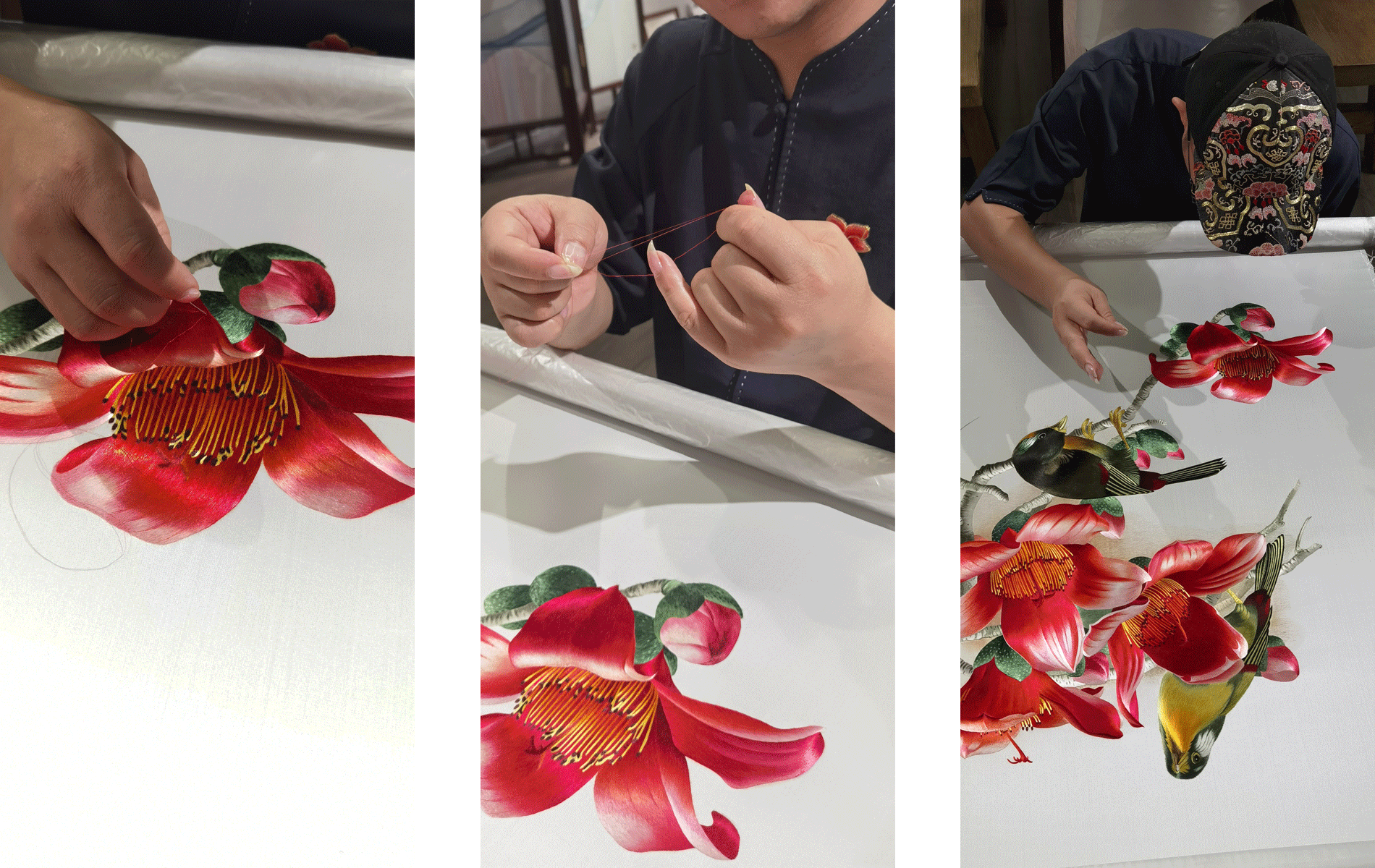

In the following three years, Wang traveled between Guangzhou and Foshan, studying embroidery on weekends while working in security during the week. His embroidery skills gradually improved. Wang’s teacher often praised him for his color sense. “They said I’m a gifted embroiderer, sensitive to color,” Wang said. “For example, people usually use three to five colors for a piece of kapok, I use more than a dozen, creating a natural transition of light and shadow.”

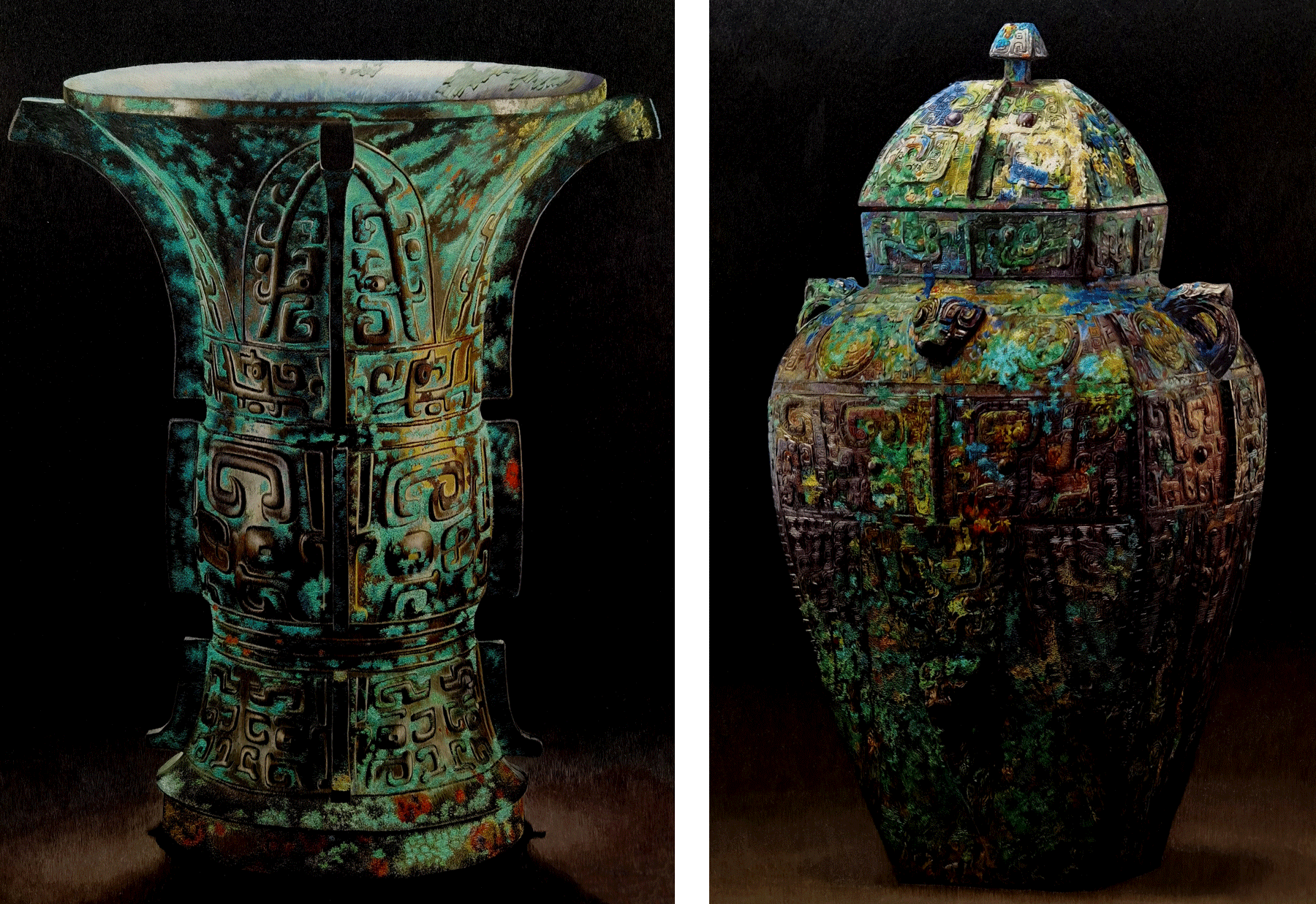

When embroidering, Wang is usually immersed from dawn to dusk, practicing for more than 10 hours a day. As his techniques improved, he was eager to create more than just flowers and birds and began incorporating his favorite historical relics into Cantonese embroidery, innovating within the traditional craft. For one bronze artwork piece, he spent three months in the museum observing how bronze rust changes under light. He then meticulously cut the fine silk and stacked it in layers to capture the intricate details of aged bronze, a process that took a whole year.

With his growing expertise, Wang resigned from his job and opened a small embroidery store in Guangzhou. Three months later, a customer walked in and was impressed by the embroidery he found. He didn’t believe that it was Wang who had created the works. “I told him to come back tomorrow, and I would embroider in front of him,” Wang recalled. The next day, the customer did come back. After witnessing Wang’s skills, he bought three pieces.

The encounter marked a turning point, and Wang’s embroidery store business flourished. By 2018, he had expanded to seven stores across the city.

Evolving with times

Despite his success, Wang wonders why Cantonese embroidery, which has been passed down for thousands of years, has fallen into obscurity. “When people think of embroidery, they always mention Suzhou embroidery. How do we change that?” he said.

Thanks to modern technology, he turned to popular short video platforms like Douyin, China’s version of TikTok, to showcase his creative process and finished works. Through these short videos, his intricate designs — rusty bronzes, horse manes, and soulful character eyes — could reach a wider audience.

Wang no longer hides his identity as an embroidery artist. When getting a manicure, he asks nail technicians to sharpen his nails for better silk splitting and carries hand cream to maintain his hands. As societal norms evolve and gender stereotypes fade, Wang feels confident when practicing embroidery on camera, finding his male identity a unique selling point in the field.

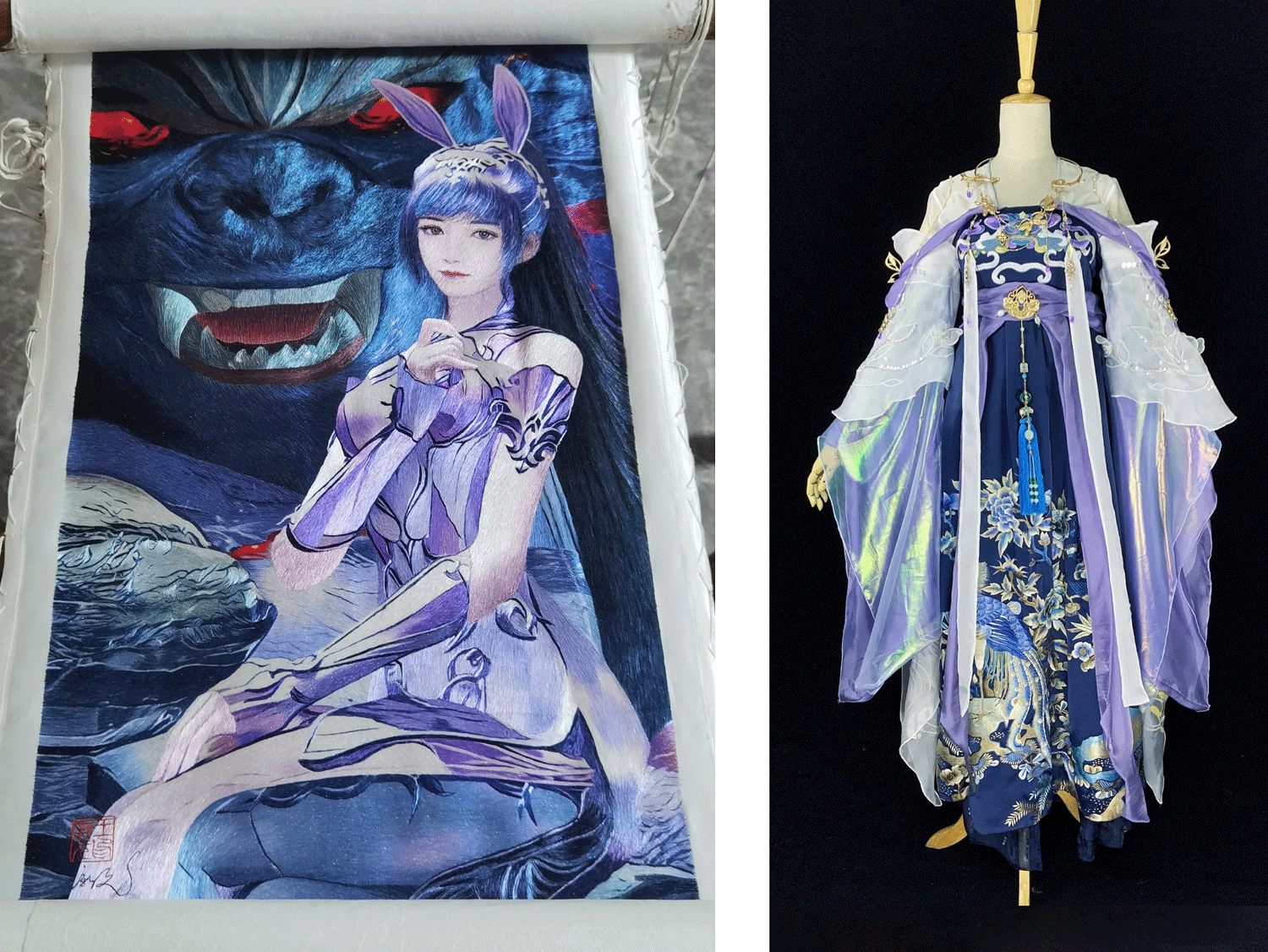

Wang firmly believes that traditional skills must evolve and innovate to thrive and connect with the market. To target younger audiences, he has created video game-themed pieces inspired by popular titles such as “Soul Land” and “Honor of Kings,” all of which have gained traction online, boosting offline sales. “I came to buy pieces after seeing his works on Douyin,” customers often remark when visiting his stores.

Beyond sales, Wang hopes to revive Cantonese embroidery and cultivate a deeper appreciation for the craft. He wants people to understand the stories behind the craft and see the dedication of generations of artisans. “What’s made by hand can’t be replaced by modern technology,” he said.

Reported by Li Jingjing.

A version of this article originally appeared in Beijing Youth Daily. It has been translated and edited for brevity and clarity, and is republished here with permission.

Translator: Eunice Ouyang; editors: Xue Ni and Elise Mak.

(Header image: Wang Xinyuan works on an embroidery piece. From @广绣王新元 on Weibo)