Pema Tseden’s Other Legacy

Last May, the author, translator, and filmmaker Pema Tseden died of a sudden heart attack in Lhasa. While the news came as a shock to all who knew him, myself included, the events of the past year prove that he has not been forgotten. His last film, “Snow Leopard,” released posthumously, won the Grand Prix at the 36th Tokyo International Film Festival last November before premiering in cinemas on the Chinese mainland in April.

But Pema Tseden’s films are only one part of his legacy — he was also a prolific writer who produced 46 short stories in both Tibetan and Chinese.

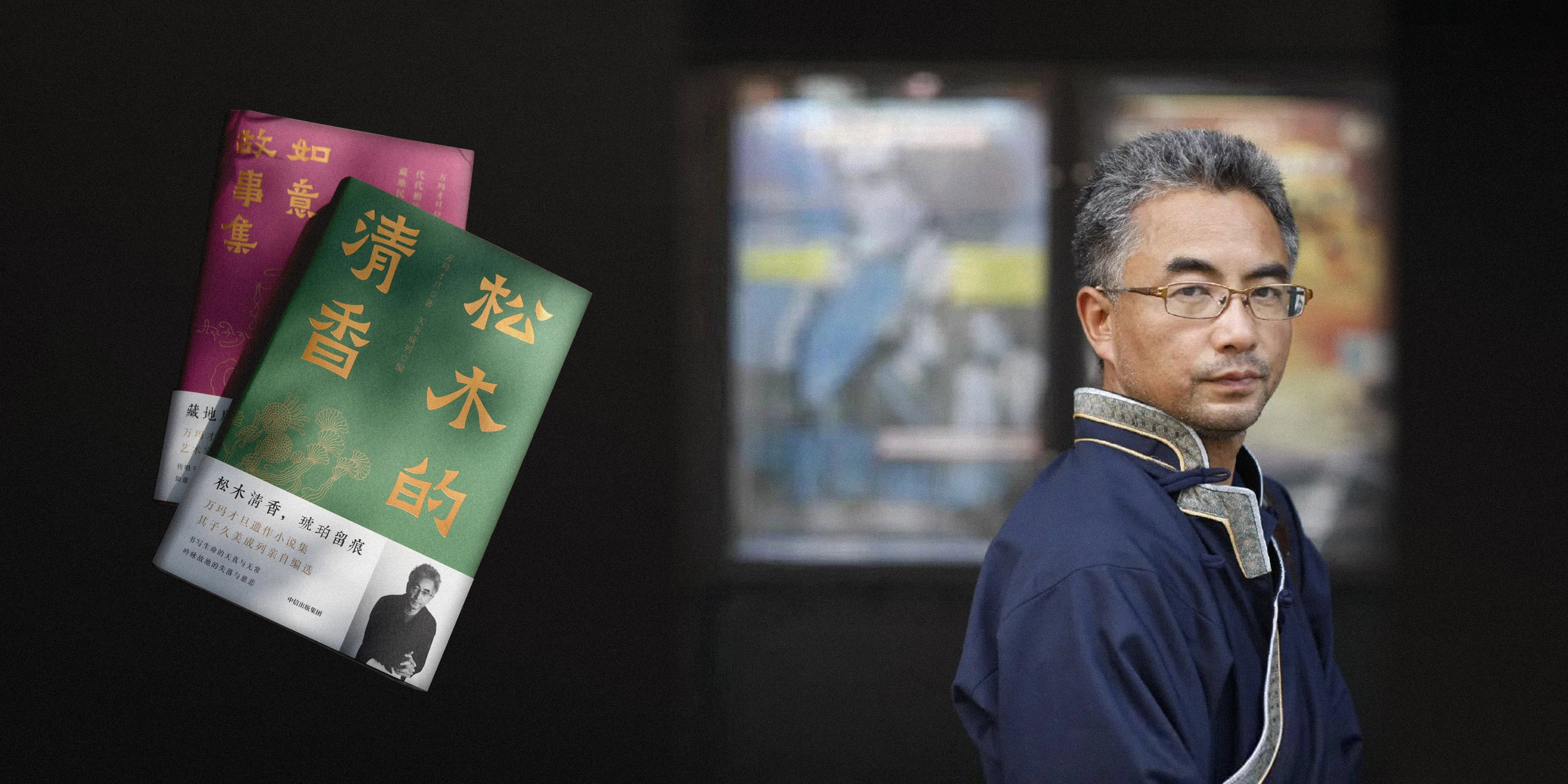

The last two of these — the fiction collection “Fresh Scent of Pine Wood” and a compendium of translated folklore “Tales of the Golden Corpse: Tibetan Folk Tales” — finally hit stores this May, on the one-year anniversary of his death. Their publication was something of a pet project of mine: my way of paying tribute to a great, if sometimes overlooked, literary talent.

Pema Tseden’s career defies easy categorization. An auteur who wrote and directed his own scripts, he was equally at home writing screenplays and novels. And he did so in two languages — Tibetan and Chinese — often translating his own work from one to the other.

Although Pema Tseden grew up in a Chinese-speaking environment and was in third grade by the time his region revived education in minority languages and scripts, Tibetan was his mother tongue. His grandfather, a monk in the Nyingma sect of Tibetan Buddhism, raised and educated him, taught him Tibetan, and helped him recite the scriptures. Their loving relationship would prove the foundation of Pema Tseden’s creative life.

After graduating from junior high, Pema Tseden was admitted into a high school in the northwestern province of Qinghai. It was there that he met the famous Tibetan poet and writer Dondrub Gyal, and under his guidance began his literary journey. Highly influential to the generation of Tibetans who came of age in the 1980s, Dondrub Gyal was the quintessential bad boy poet: Eschewing custom, he wore his hair long, donned sunglasses and a long trench coat, and smoked in class. He could recite epics like the “Ramayana” and spoke endlessly about poetry.

But Pema Tseden didn’t just draw influence from Tibetan literature: In addition to Tibetan classics like “The Life of Milarepa,” he immersed himself in work like the 17th-century classic “Dream of the Red Chamber,” Russian literature, and popular romances. He also read many of the realist noels and avant-garde writers who emerged in China in the late 1980s, including Yu Hua, Yan Lianke, Ge Fei, Su Tong, and Can Xue.

Their influence can be seen in his first published story, “Men and Dog,” which came out in the Tibet Literature magazine in 1992, when he was just a freshman in college. The narrative is simple: A dog lives on a mountain inhabited by three households of shepherds. One night, one of the households witnesses a marriage, another has a member who falls ill, and in the third, a child is born. A wolf arrives, and the dog vigilantly guards the herds of sheep, barking and shrieking. The people, feeling ill at ease about the sound, beat the dog to death with a staff. The next morning, they realize that the strange sounds they heard the night before were from a fight between the dog and a wolf.

“It was my debut piece, and it basically set the tone for all my other work,” Pema Tseden later told his biographer. “What remains is really only one emotion, a slight pessimism.”

In 1991, after four years spent as a primary school teacher, Pema Tseden was admitted into the Tibetan Language and Literature major at Northwest Minzu University in Gansu province; he would eventually receive a master’s degree in Tibetan-Chinese Literary Translation from the school. As part of his degree, he needed to translate a text from Tibetan to Chinese; he picked the “Tales of the Golden Corpse,” a compendium of classic folktales from the region.

“I needed to get some practice translating, so I translated the ‘Tales of the Golden Corpse,’ which greatly influenced me when I was young,” he recalled. “The narratives and dialogues in those stories were very simple, but they inspired me.”

Indeed, both his short stories and scripts were greatly influenced by folk literature and Tibetan literary traditions. Pema Tseden listened to many folktales growing up, and later on he would retell these stories to others, giving him an ear for concise language and structure. In 2009, he published a full Chinese translation of the “Tales of the Golden Corpse,” affixing “Tibetan Folk Tales” to the title. That same year, he completed work on his first feature film, “Soul Searching,” part of his graduate thesis at the Beijing Film Academy. It would go on to win the Jury Grand Prix at the 12th Shanghai International Film Festival.

But Pema Tseden believed that writing fiction allowed for more self-expression than filmmaking, and the pleasure and satisfaction he derived from writing was greater than that for the films he made. When he wrote short stories, he tried to work quickly, going from inspiration into text in a single bound. He would liken writing to dreaming. A common trope in Tibetan literature is for the storyteller to abruptly enter different states: When reciting “The Epic of King Gesar,” for example, the storyteller must channel completely different voices. They themselves might be illiterate, but through the story, their language can become beautiful and sophisticated. If uninterrupted, these recitations could last for several hours. Pema Tseden always hoped that his own works could mimic such a state — dreamlike, trancelike.

“Searching, but ultimately not finding — the theme of loss runs through all my writing,” Pema Tseden said. He used stories to reconstruct his own understanding of the Tibetan world he grew up in, even as that world changed and grew more distant.

His posthumously released short story collection, which I had the privilege of working on, was compiled by his son, himself a filmmaker, Jigme Trinley. The pieces are presented in backward chronological order, from his last novel to his debut. In addition to “Fresh Scent of Pine Wood,” the last story he completed before his death and the one that gives the book its name, it includes some of his other most representative works, such as “Men and Dog,” the novel from which “Soul Searching” is based off. One standout is “A Red Cloth,” which tells the story of two people’s experiences across a single day. One is blindfolded and ends the day unchanged; the other goes through an entire lifetime, aging, falling ill, and eventually dying.

It’s a curious fable — the orphaned legacy of an artist gone far too soon.

Translator: Matt Turner; portrait artist: Wang Zhenhao.

(Header image: A portrait of Pema Tseden (right) taken in 2016, and a collection of his fiction. Courtesy of Liu Dayan and CITIC Publishing Group)