Creative Chaos: The Chinese Students Pushing the Limits of Art

When it comes to university majors with the most eccentric students, the experimental arts program at Beijing’s Central Academy of Fine Arts (CAFA) would definitely make the list.

Every year, up to 30 students are recruited to the major, which is under the School of Experimental and Sci-Tech Arts. Even the questions in the entrance exam are far from traditional, often touching on far-out concepts and topics. As a result, it’s known as the hardest class to get into at CAFA.

Once enrolled, students feel as though they have entered a vast wilderness. In their first class they are asked to “teach” the department head and introduce what truly interests them. The course also has no fixed requirements, other than the pursuit of constant artistic experimentation for the purpose of self-expression.

Labor of love

In April, with just over a month to go before her CAFA graduation exhibition, Shui Jiayi decided to scrap her initial project plan and start afresh.

Originally, she was going to turn dozens of oranges into various handmade squeeze toys. She had already bought the materials and made about 10 toys. But halfway through, she felt that her work did not align with her intentions.

Unlike students in other majors at the school, like oil painting or sculpture, who plan their graduation projects a year in advance, standard practice for experimental art students is to start their projects just one or two months before the deadline.

The theme of Shui’s graduation project was the one thing she was certain about: it would be inspired by her mother. The idea of making squeeze toys from oranges came from a desire to experience repetitive labor like her mom had while working in a factory in the southwestern Sichuan province. Over her career, Shui’s mother has had a variety of manual jobs including packing pork at a slaughterhouse, peeling chicken feet, and making seasoning packets for instant noodles.

However, Shui realized soon after starting the toy project that it wasn’t a good fit — other than being a hometown specialty, oranges had no connection with her mom.

As her mother’s only interest is buying household goods in bulk, largely to save her family money, Shui grew up surrounded by wholesale items. Shui’s slippers were always cheap and several sizes too large. Once, a classmate at school asked her, “Why are you wearing your dad’s shoes?”

“Everything at home has been bought wholesale. So, home for me is no different from any other space,” she says. This negative view of her mother’s shopping habits has been a constant for Shui. It also became the starting point for her new graduation project: By living in a cramped space filled with wholesale goods, might she better understand her mother?

In early May, Shui began putting her plan into action. In a 5-square-meter underground storage unit in Beijing, she began to assemble random items, such as clothes hangers, instant coffee packets, and plastic slippers, all bought at the lowest price possible from the e-commerce platform Pinduoduo. Filling the small unit from wall to wall, she spent 6,000 yuan ($825) in total. She even made small furniture out of various items: tissue boxes became a desk, wet wipes formed a pillow, and paper rolls and T-shirts padded out a mattress.

“True art must be deeply connected to you. To discuss someone’s art is essentially to discuss the artist,” Shui says, adding that from this perspective, one can see seemingly meaningless objects come to life.

The production process is also part of the artwork. The creativity, novelty, emotional impact, and self-expression contained within a piece is often what artists care most about.

Several students claimed to have experienced “torment” while completing their graduation projects.

In Peng Chong’s work “An Internet-Famous Artist’s 30 Days of Stardom,” he attempted to use various marketing methods to become a celebrity and establish a sizable online presence within a month. He paid news media for publicity, walked the runway at the Ullens Center for Contemporary Art, one of the largest art museums in Beijing, and bought scalped tickets for a movie premiere filled with stars. He spliced together footage of these endeavors into a performance art video and then decorated his graduation exhibition venue like a red-carpet event, inviting visitors to “check in.”

The experiment was quick to execute, but it had taken him half a year to nail down the idea.

Repeating cycle

Almost every experimental artwork is a form of self-revelation.

Ni Ming has spent much of this past year in a state of internal struggle. He believed he needed to have a grand theme for his graduation project, one appropriate for such an important occasion. So he initially proposed to his supervisor a performance art piece mimicking M.C. Escher’s endless staircase in “Ascending and Descending,” in which he would film himself continuously climbing stairs.

When the supervisor asked him what he wanted to express, Ni shared his recent sense of confusion: “I have felt especially powerless. With graduation imminent, I don’t want to enter a kind of life that is just constantly repeating itself.” The supervisor was impressed and urged him to “hold onto that feeling.”

Soon after, the supervisor asked Ni to pack his things and go to a rural area in the eastern Anhui province, all expenses paid. On arrival, Ni saw that the supervisor, who was there organizing a summer trip for some other students, had helped borrow a camera and tripod for him in advance, telling him to “see what you come up with here.”

Ni wandered the countryside for a long time, thinking about the concept of a “repeating cycle.” Stopping at a crossroads, he noticed a rice field to his left, and a brand-new Japanese-style guesthouse charging upward of 2,000 yuan a night to his right. Ni felt a strong emotional resonance. He grew up in a village in the eastern Shandong province before moving to the metropolis of Beijing to study. Now, with graduation imminent, the conflict he felt was at its peak. He faced a choice between applying for work at a major company in the city, or returning home to the countryside to be a teacher.

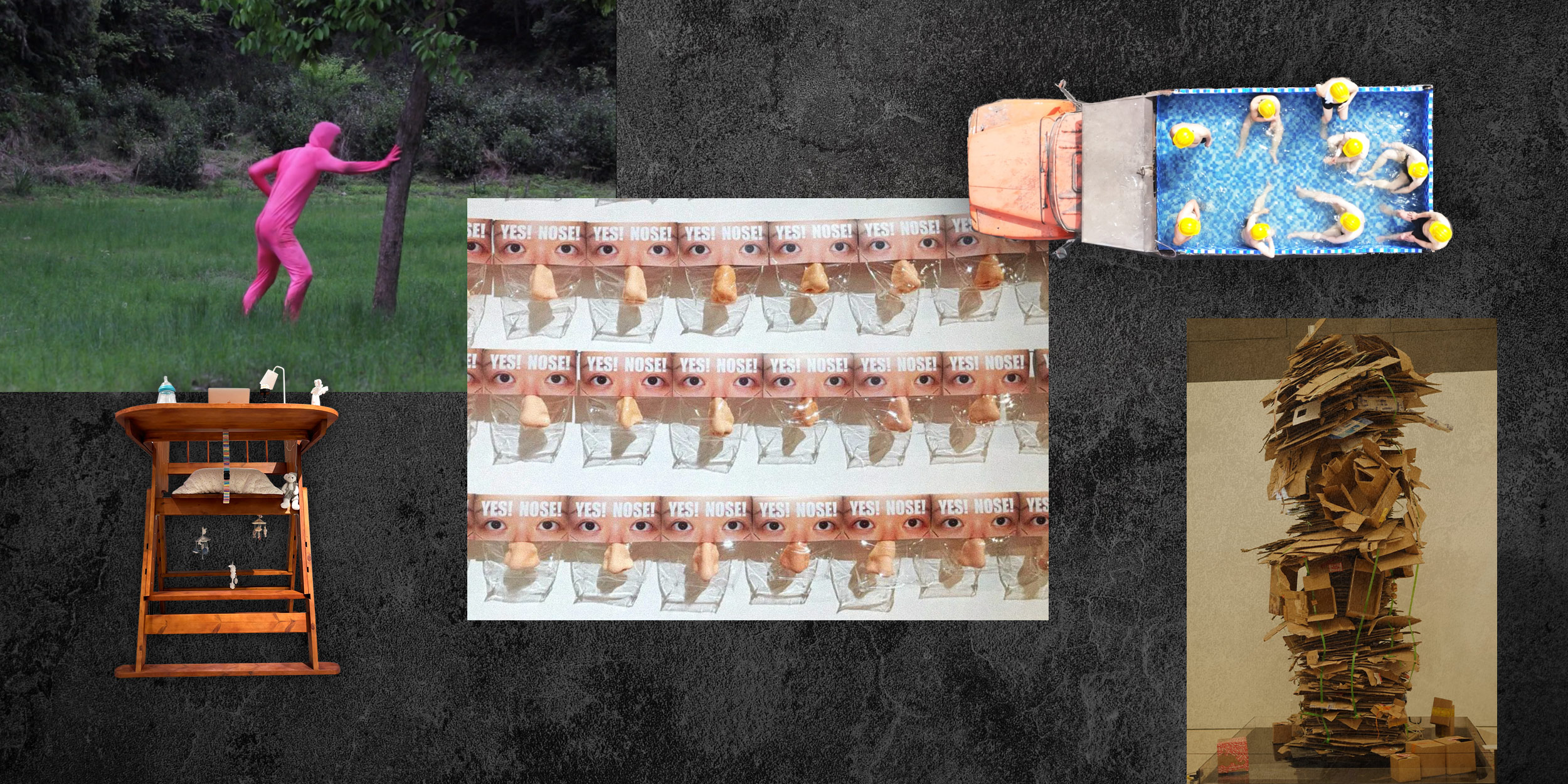

Ni presented his inner struggle stemming from indecision in his graduation project, “I Practice Earnestly,” a filmed performance art piece in which he does exercises such as the horse stance and frog jump and performs somersaults in the mountains while wearing pink overalls. One segment shows him slapping himself for five minutes between two weeding machines, one red and one blue.

The avant-garde nature of Ni’s art left some members of his audience confused. In contrast, the work of his contemporary, Li Qing, appeared more straightforward. Li, recalling how her father had once pointed to his truck during the annual Spring Festival holiday and said, “This is what gets you through university,” decided to transform a large truck into an outdoor swimming pool as an ode to his livelihood.

Li and her father’s truck are the same age. She remembers how her father used to haul coal in the northern Shanxi province when she was a child. Whenever he returned home to clean up, his clothes and the water they were washed in would be stained black. By hauling coal, her father was able to buy a property in Yangquan, a city in the east of Shanxi. After the mines closed, he earned money to support his daughter’s art education by hauling water to villages that lacked supplies. “Without this truck, I would not be where I am today,” she says.

Li spent half a year designing her project and came up with many ideas. She ultimately decided to convert the truck bed into a pool. Her father also participated, helping her pave its mosaic tiles. After finishing the conversion, Li invited her cousin and his colleagues, who all work as miners, to play in the pool. Wearing yellow safety helmets, their bodies pale after years spent working underground away from the sun, they waded in the water and posed for the camera. The artwork won first prize at this year’s graduation exhibition.

‘Free-range’ education

For most students who go through the highly structured and goal-oriented gaokao, China’s national university entrance examination, the four-year experimental arts program at CAFA will appear free-wheeling to the extreme.

In the first course, one tradition is to reverse the roles of teacher and student, with the new pupils being called upon to teach the department head. Each freshman must make a PowerPoint presentation on a topic of interest.

For this, Yin Xinhang discussed rhinoplasty, presenting details on which celebrities have undergone nose jobs or talked publicly about plastic surgery. She chose the topic due to having been dissatisfied with her own nose since she was a child. For her graduation project, she made 386 to-scale models based on various people’s noses. “At the end of this process, I no longer cared about whose nose looks good. They are all just lumps of flesh,” Yin says, explaining that her artwork had freed her from her obsession.

The experimental art major’s curriculum is almost entirely unstructured. Instead, it emphasizes a “broad but not necessarily proficient” education. Here, students can learn poetry, woodwork, and web design, among other things, all in the hope of developing divergent thinking.

Shui says her most memorable class was zoo fieldwork, during which she spent a week observing giraffes. She thought about the documentary “Animal World” and how the creatures would fight with their long necks on the savannah — a form of entertainment for them. Later, she designed a toy ladder as tall as a giraffe, allowing her (hypothetically) to fight with them herself.

The CAFA graduation exhibition officially opened on May 18, showcasing the results of the students’ four years of a “free-range” education.

Shui’s final piece, titled “Use,” involved living in her “home” for 15 days in open view of the public. In the final two days, viewers were able to buy a bag for 18 yuan and use it to take any item from the storage unit home, an extension of the artwork.

When asked what the future might hold for her and other experimental art students, Shui pondered for a while. “It’s a common question, but hard to answer. Our major’s most obvious career path is to be an artist, but do companies hire artists?”

Most graduates end up pursuing further studies or going abroad, with few directly entering the workforce. Shui mentions an older student she really admires who still doesn’t have a full-time job, instead taking only part-time work to cover her expenses and dedicating most of her time to unprofitable but fulfilling creative projects. For Shui, it’s the ideal lifestyle.

Reported by Xu Jiajing and Qu Mei.

A version of this article originally appeared in Oh! Youth. It has been translated and edited for brevity and clarity, and is republished here with permission.

Translator: Vincent Chow; editors: Xue Ni and Hao Qibao.

(Header image: Visuals from @实验主义者 on WeChat, reedited by Sixth Tone)