Fool’s Gold: Fake Antique Livestreams Prey on China’s Elderly

Instead of going to work or picking up his grandchildren from kindergarten, Kou Xiaoxia’s father, Kou Shoule, has squandered his savings on a sinister new addiction: Binge-watching livestream shopping channels for fake antiques, a scam that has cost him nearly 300,000 yuan ($42,000) since March.

“Our whole family has tried to persuade him (to stop),” rues 32-year-old Kou from Weifang in eastern China’s Shandong province. “He won’t listen to a single word I say. Every time we talk, it turns into an argument, ending with him accusing me of hindering his path to wealth.”

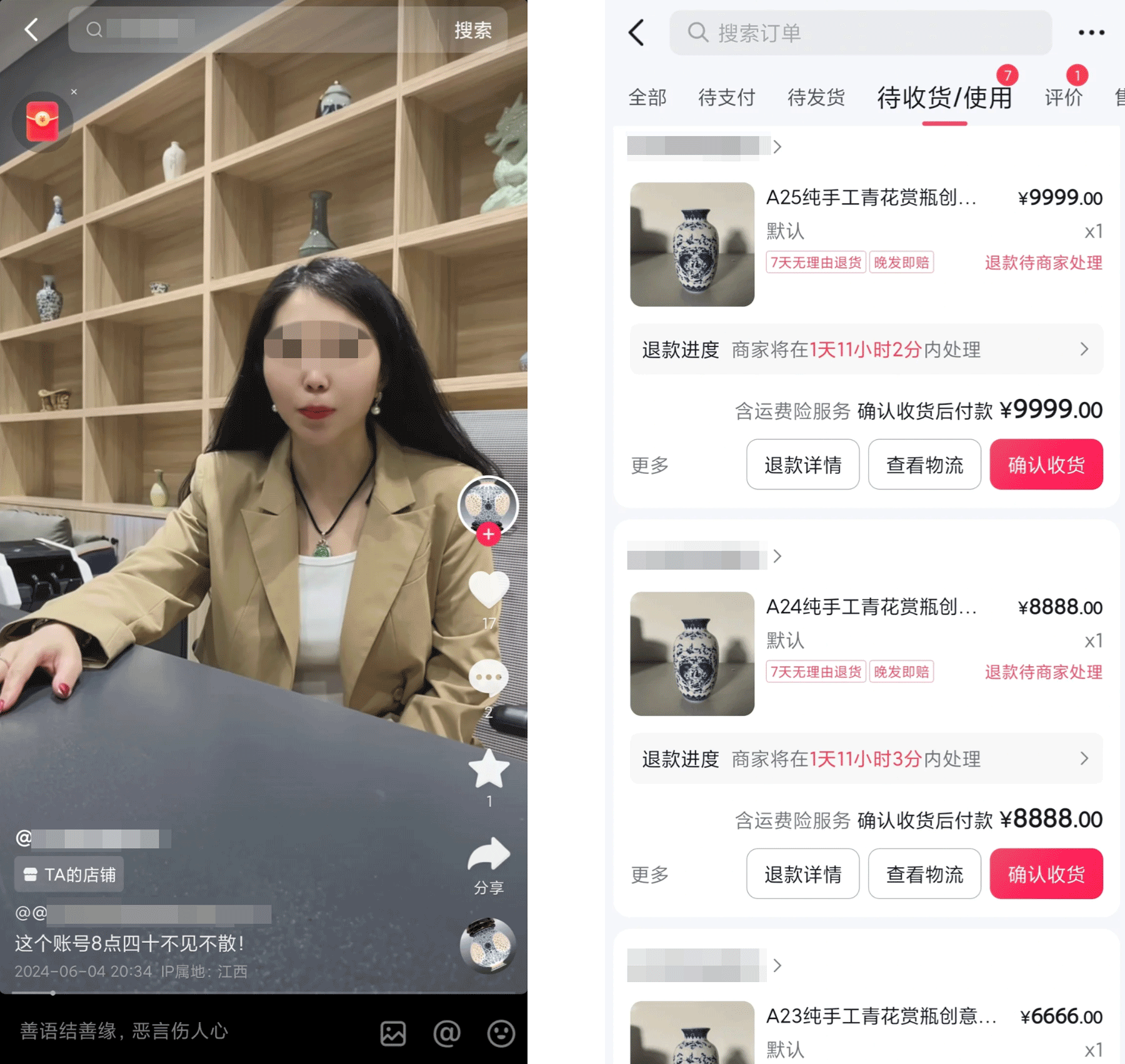

From 9,999 yuan for a single bronze zodiac animal head purportedly from the Old Summer Palace in Beijing to 2,380 yuan for a piece of blue and white pottery, such livestreamed sales of so-called antiques and collectibles are part of an insidious fraud targeting middle-aged and senior Chinese netizens with modest savings.

In recent months, these predatory schemes have skyrocketed, with a flood of livestreams hawking counterfeit items like commemorative coins, stamps, and artwork on domestic short video platforms. Over the past few months, investigations have led to the arrest of several fraudsters, underscoring the severity of such schemes.

“These collectibles, priced from thousands to tens of thousands of yuan, are often presented with dramatic narratives and historical claims,” hosts typically declare in their livestreams. “They could potentially be auctioned for millions or even tens of millions in the future.”

The promise of high returns and buyback guarantees has proven irresistible to older consumers with limited knowledge of antiques. While multiple domestic media reports highlight the financial devastation caused by these scams, victims’ relatives recount how they’ve created rifts within their families.

Kou’s relationship with her father has deteriorated as he stubbornly clings to the hope of striking it rich, ignoring her pleas and warnings. Other families say their elders have begun hiding purchases from their children, deepening the divide and isolating them further as they fall deeper into the scam’s web.

Recovering the lost money is also an uphill battle. Kou says that to get the authorities to act, she must gather enough evidence to file a valid complaint against the host on the livestreaming platform, while also convincing her 59-year-old father to cooperate.

But now, she’s found solace in a growing community of support from others facing the same struggles. Many victims’ family members have created a group chat on the social super app WeChat, where they share updates and advice on filing online complaints and reclaiming money.

Despite these efforts, the perpetrators of these schemes continue to create new accounts to engage with their clients. Legal experts say these businesses’ actions constitute fraudulent behavior due to false advertising, and they suggest that the livestreaming platforms should strengthen their regulations to curb the proliferation of such schemes.

Brainwashed

Kou had no inkling of the scam that had ensnared her father until he began repeatedly asking for money in March, ostensibly for medical expenses. It wasn’t until she had lent him nearly 30,000 yuan that her suspicions were aroused — despite his claims, he never visited a hospital.

Digging deeper, Kou discovered her father had been duped by a persuasive livestream host on the short-video platform Kuaishou. The host had promised that the gold, jade, pottery, and other collectibles he bought would be bought back by him at a significant profit at a later date.

“The gold items, which were purchased for around 2,900 yuan each, were touted to be worth millions upon resale,” Kou recalls.

Kuaishou is particularly popular among older users. According to QuestMobile, a leading mobile internet business intelligence service provider in China, the platform had 114 million users aged 51 and above in 2023. In September 2023, this demographic also spent the most time on Kuaishou, averaging 2.04 hours daily compared to 1.87 hours on Douyin, the Chinese version of TikTok, and 1.51 hours on WeChat.

According to Kou and other victims’ family members, the livestreams on Kuaishou typically sell these high-value “collectibles” using dramatic plots. “They never introduce what the product is,” explains Kou. “Instead, they showcase its value through a narrative scenario and then put it on sale.”

During these livestreams, two factions might engage in a heated debate, with one seemingly malevolent group attempting to seize a precious artifact. The other side would then plead, explaining they had invested significant money into the antique and seeking support from the audience to keep the item temporarily.

They promise to buy it back at a price nearly a thousand times higher in the future, once the situation is secure. Others craft a persona of wealth, displaying a home filled with antiques and frequently participating in high-end auctions.

To avoid scrutiny, such livestreams have even found ways to circumvent the platform’s rules. They use small captions that read “situational enactment, for entertainment purposes only,” which are barely discernible to senior netizens.

“They no longer use the censored term ‘buyback’ directly,” says Kou. “Instead, they say, ‘If you wish to live a good life with your children and want to be free from worries about food and clothing in the future, then bid on it.’” Most hosts call their potential clients “fathers” and “mothers” to forge intimate bonds, further manipulating their audience.

When Kou discovered her father had been conned, she immediately sought to report the incident to the police. However, they informed her that since the purchase was voluntary, only her father could file a complaint, and he fully believed the host’s narratives.

Kou also tried to return the counterfeit items. “It’s easier to return items within three months of delivery; it becomes difficult after a year,” she explains, adding that she did manage to reclaim around 9,000 yuan from three returns. If the online store receives too many complaints and return requests, securing a refund becomes even harder.

But her efforts came at a cost. After trying to protect him, Kou recalls her father saying: “You don’t have to worry about me in the future, and we can just sever our relationship.”

According to Kou, creating discord within the family is a tactic such sellers often employ. She says that hosts warn their followers that returning the items would result in being blacklisted or losing future opportunities to participate in auctions or buybacks.

They even persuade their clients to hide the purchases, claiming that anyone who asks them to return the items is hindering their path to wealth. Kou’s father has now hidden all the items he purchased after she managed to return three of them.

This pattern of secrecy and isolation is not unique. In Shandong, another 68-year-old victim has also concealed her purchases from her family.

The victim’s daughter, surnamed Zhao, discovered the deceit in May when she found her mother’s secret stash of suspicious collectibles under her bed. “My mother was very flustered after I found out and told me not to interfere,” Zhao tells Sixth Tone, using only her surname to protect her privacy.

Her mother had bought over 20 items, including white pottery, vintage paper money, and coins.

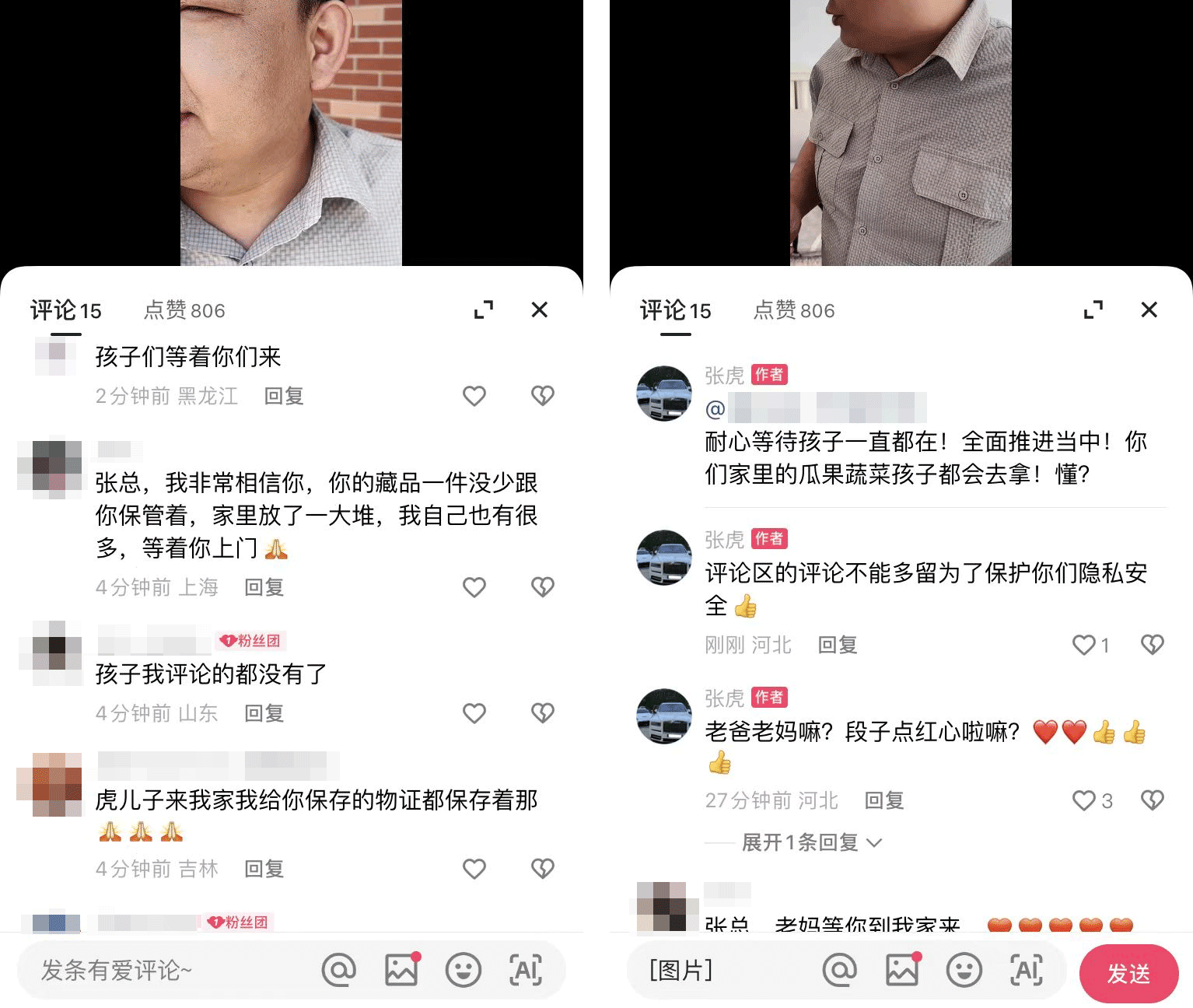

Like the elder Kou, Zhao’s mother was convinced by a host, called Zhang Hu, on Kuaishou that the items she bought were valuable antiques that would be bought back at high prices.

“I told her it’s a scam, which led to a lot of unpleasantness,” says Zhao. “When I said I wanted to call the police, she constantly threatened to jump off the building, saying that if I reported it and returned the goods, she would jump.”

Victims’ family members tell Sixth Tone that when the promised day for the buyback or auction arrives, the hosts delay with various excuses, such as claiming they’ve been in a car accident or have more important matters to attend to. Some even swindle the clients into paying for travel expenses.

“The elderly have complete faith in the host, believing him over us,” says Zhao. “I’m really frustrated that she’s actually siding with the con artist.”

Fighting back

With the majority of scam victims unwilling to cooperate, exasperated family members have banded together to take on the livestream hosts who exploit the use of platforms like Kuaishou, Douyin, and WeChat.

Statistics compiled by these families reveal a troubling pattern: dozens of middle-aged and elderly individuals have been defrauded, with losses reaching millions of yuan.

Wei Wei, a partner at Beijing JAVY Law Firm, explains to Sixth Tone that these livestreamers must bear civil liability if they knowingly misrepresent the value of the collectibles they sell.

“These cons typically involve false advertising, misleading statements, or unfulfilled promises, leading consumers to make transactions based on these misunderstandings and allowing the operators to profit,” says Wei.

She adds that the businesses and hosts involved may face administrative penalties, and in severe cases, their actions could constitute a crime.

With cases rising, law enforcement has now begun to take action against these fraudulent schemes.

In May, police in Kangping County, in the northeastern Liaoning province, detained a criminal group that tricked people into buying counterfeit antiques through staged plots and fake personas online. According to the police report, the mastermind, surnamed Li, and three accomplices illegally profited over 280,000 yuan from this scheme.

In the same month, public security authorities in the eastern Zhejiang province alerted the public to an ongoing case where a senior was lured into purchasing 43 pieces of rough jade for 5,000 yuan each during a livestream. The victim was promised a buyback by a so-called “Burmese prince” offering between 800,000 and 2 million yuan.

Kuaishou did not respond to Sixth Tone’s request for comment, but a customer service agent acknowledged the platform is aware of the issue, having received multiple reports of such livestreams.

The agent underscored that Kuaishou has zero tolerance for fraudulent activities but admitted difficulties in monitoring them, as hosts and their accomplices frequently create new accounts using others’ IDs.

Kuaishou’s customer service also advised that the most effective reports include photos of the purchased items, chat histories with the seller or streamer, and recordings of the livestreams.

But according to many in the WeChat support group, this is easier said than done. Many say they have attempted to file complaints against livestreamers and related online stores on Kuaishou for fraudulent activities, but gathering sufficient evidence to block these accounts has proven challenging.

Filing a report and requesting a refund require transaction numbers and verification from the purchaser, complicating the process for family members trying to intervene.

When complaints are valid and supported by sufficient evidence, Kuaishou takes action against the perpetrators, including deducting platform credit points, withholding security deposits, and imposing temporary or permanent bans on accounts.

However, livestreamers frequently create new linked accounts to continue their operations despite being banned by platforms.

“Our side can only deal with one of these hosts’ current accounts,” the Kuaishou customer service representative said. “Since one ID card can only be bound to one account, it is beyond our monitoring capabilities if they have a team or use relatives’ ID cards for registration.”

Wei noted that the proliferation of fraudulent livestreaming rooms online could be attributed to multiple factors, including limited supervision, the low costs associated with executing such schemes, and the heightened vulnerability of senior netizens.

“If the platform fails to adequately fulfill its obligations of reviewing and managing content, thereby causing harm to users’ rights and interests, it will be held jointly and severely liable for the consequences,” she says.

Xie Shu, an associate professor from China University of Political Science and Law, suggests relevant platforms further strengthen their bars of entry for livestream sellers and establish a blacklist system to reduce the possibility of them “coming back.”

“Hosts wishing to sell goods must verify that the account’s real name matches the actual user through methods such as facial recognition, uploading business licenses and other credentials, and enhanced identity verification,” Xie recently told domestic media.

While concerned family members of scam victims continue to file complaints to shut down the hosts’ accounts, their ability to intervene with their own parents is limited by the fear of escalating tensions.

These days, Kou says she barely talks with her father after multiple quarrels, and Zhao logs into one of her mother’s Kuaishou accounts almost every day to monitor any recent purchases or interactions with the host.

Editor: Apurva.

(Header image: Visuals from VCG, Kou Xiaoxia, and Xiaohongshu, reedited by Sixth Tone)