The Many Histories of Chinese Vegetarianism

Back when I was a visiting researcher in Shanghai, my daily routine included stopping for lunch at a large vegetarian buffet near the Fudan University campus. The trick was to get there before the seats filled up, which they invariably did, mostly with retirees and workers — people who liked the food and knew how to sniff out a bargain.

That scene bears little resemblance to the new wave of elite vegetarian restaurants popping up in major cities across China. Instead of bargain-hunting retirees, these restaurants chase Michelin ratings. And they’re succeeding. China now boasts 22 Michelin-ranked vegetarian restaurants. Shanghai alone has three.

Being vegetarian in China rarely comes down to any one thing. There are as many explanations as there are people. Besides ethical or religious reasons, China has a long tradition of gourmet vegetarians: people who see a meat-free diet as the only true calling of a culinary connoisseur.

But they’ve always been a select group in a country that otherwise has a special love for meat.

Just like in classical Greece, ancient Chinese political rituals demanded animal sacrifices — lots of them. The meat from these sacrifices was not something to waste. Gifts of meat — fresh, cooked, or preserved — were so important that early China called its rulers “meat eaters.”

Even as China’s cuisine evolved, meat remained central. From the markets of the Song dynasty (960–1279) capital Bianjing, in what is now the central city of Kaifeng, to the pages of Qing dynasty (1644–1911) fiction, China never lost its love of meat.

China’s taste for meat hasn’t changed, but people’s ability to procure it certainly has. By the 1990s, people were eating more meat than ever before. Pork is king in China, which famously maintains a “strategic pork reserve.”

But then, as now, there were those who simply didn’t want to eat meat. To understand the reasons, just look at some of the words for vegetarian diets in Chinese: shu means a diet of green plants; su connotes simplicity and purity; and zhai conjures up an unmistakably Buddhist image. Each one means something a little different, as well. A Buddhist zhai diet also avoids stimulants like onions and garlic, while su is often seen as less rigorous. (Vegans eating away from home can make their point clear by using the term chunsu, or “strictly su.”) And that’s not counting lesser-known traditions, like the Taoist vegetarian diet, which also avoids both meat and stimulants, but a different set of stimulants than Buddhists. Or the Confucian tradition of eating a simple diet during mourning: no meat, refined grains, or cooked dishes.

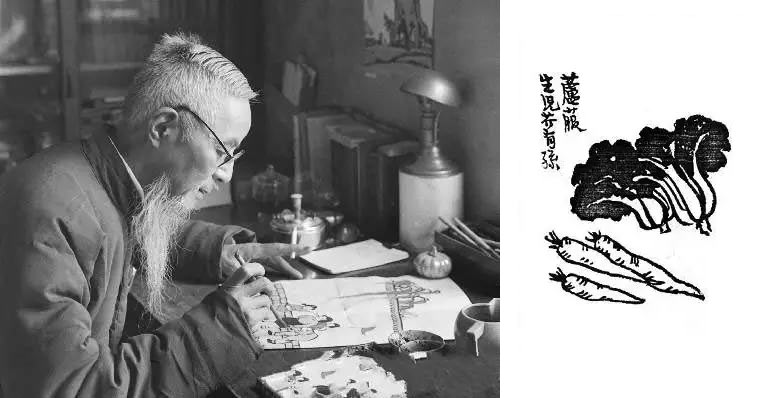

Another common reason for adopting vegetarianism was the desire not to harm animals. The inspiration wasn’t necessarily Buddhist. In his “Introduction to Eating Su,” the late-Qing scholar-painter Xue Baochen (1850–1916) recalled deciding that he simply didn’t want to cause any more suffering in this world — at least not in the service of his appetites. After being jailed in a palace power struggle, Su Dongpo (1037–1101), the Song-era cultural icon and namesake of arguably China’s best-known pork dish, wrote a poem expressing sympathy for penned animals awaiting their execution: “Pity the clams in the basket, closing their shells tight around the last drops of water; Pity the fish in the net, spitting the moisture from their gaping mouths.”

But whether it was for piety, health, or other reasons, these vegetarian traditions all shared a sense of sacrifice. You were forgoing something you wanted to eat, as well as your place in meat-eating society. For early British adopters like 19th-century Romantic poet Percy Bysshe Shelley, giving up meat was part of a scandalous non-conformist lifestyle that also included atheism and open marriages. Chinese vegetarianism was more socially respectable, but it still denied people the intimacy of a shared meal. Even if a society of meat-eaters didn’t deem you deviant, there was always a strong chance that your fellow diners might find you a bit too dull to invite back.

But not everyone. In making his case for giving up meat, Xue Baochen emphasized that properly prepared squash and bean curd could taste every bit as delicious as fatty lamb. Elite gourmands like Su Dongpo or the 18th-century poet Yuan Mei (1716–1797) regarded a vegetarian diet not as a hardship but as the height of taste and sophistication. In his classic of Qing-dynasty food writing, “Recipes From the Garden of Contentment,” Yuan comments that anyone can cook meat, but a su diet is for the elite.

Yuan had an army of cooks, but he was talking less about financial resources than cultural ones. As a scholar, he was intimately familiar with centuries of writing about the “true taste” (ben wei) of food, an aesthetic that required changing not the food but the diner.

Others prized the purity they associated with the vegetarian diet and the unparalleled elegance of a simple stew of wild herbs eaten in the quiet courtyard of a thatched roof hut. Writer Wang Zengqi (1929–1997) was so taken by a poetic mention of such a dish that he wrote a whole essay musing about the taste of sunflower and okra leaves.

At one extreme of this ideal sat the Taoist hermit, who foraged mountain plants not just for their nutritional value but also for their medicinal potency and their pure and unspoiled taste. One Song dynasty (960–1279) collection of vegetarian recipes, each written in sparse poetic prose, was supposedly composed by an unnamed recluse who lived surrounded by paintings and arcane books. A visitor who tried the author’s food declared its taste to be “beyond the mundane world.”

Today’s vegetarian gourmets inherit this quest for culinary refinement. Unlike the boisterous shared tables at my Shanghai buffet, high-end vegetarian restaurants like the ones I recently visited in the southwestern city of Chengdu are elegant and quiet. One is in a temple, others adopt a Buddhist aesthetic, while others still aim for a muted feeling that could be described as “Michelin Zen” — a kind of secular temple of taste. Notably absent are “mock” dishes that use heavily processed bean products to replicate the familiar taste and texture of meat. The aim of these restaurants is not to wean people off animal products but rather to celebrate the world of subtle flavors, flavors that come alive when diners liberate themselves from their reliance on meat.

(Header image: Details of the Song dynasty painting “Literary Gathering.” From Taipei Palace Museum Open Data)