How 1920s Shanghai Birthed the Modern Female Idol

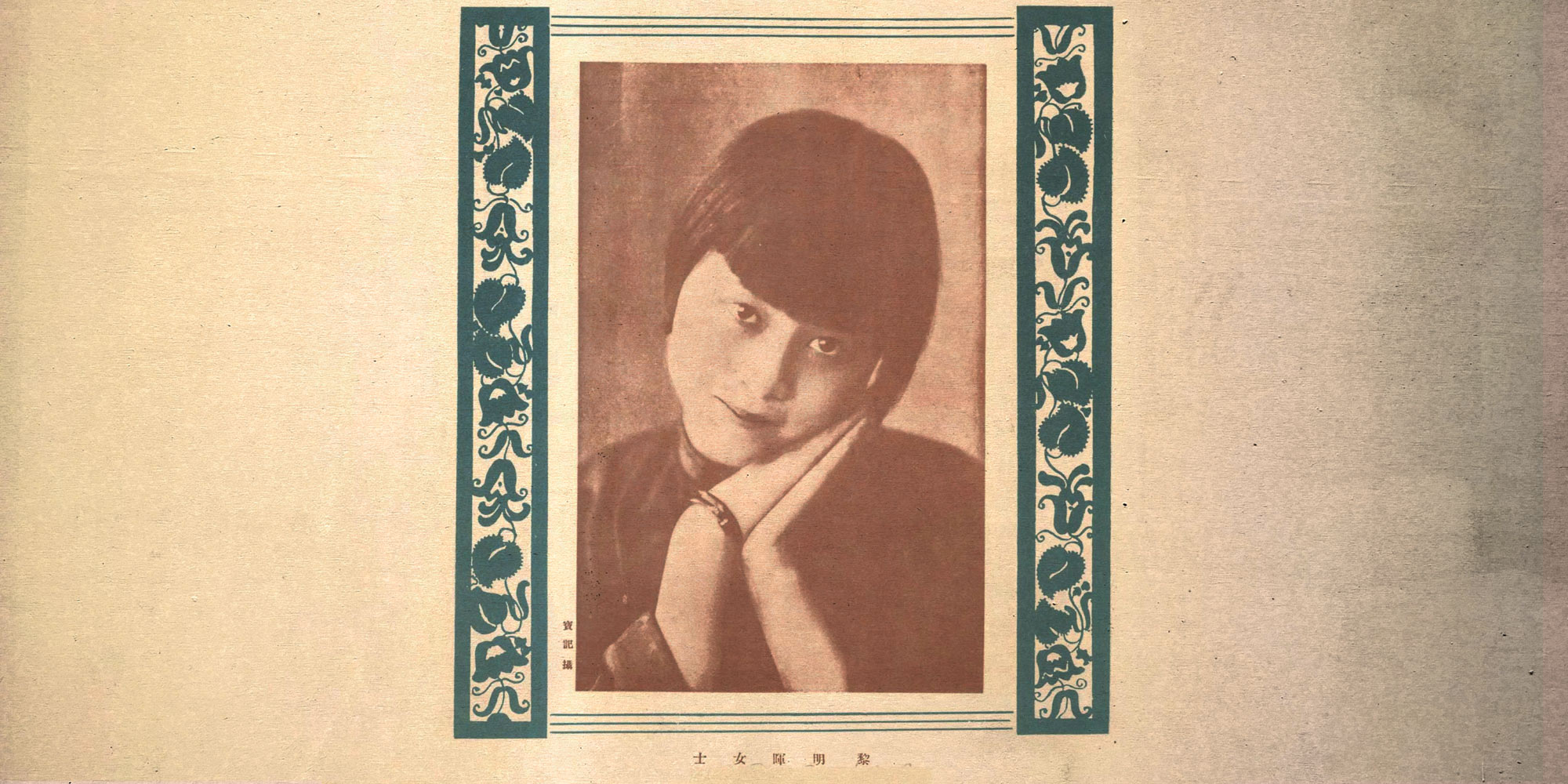

On a tranquil night in 1922, the stage of Shanghai’s Central Theater witnessed a quiet gender revolution. It was the premiere of the spoken drama “Ms. Orchid,” as produced by Shanghai Experiment Troupe, and an unlikely figure graced center stage as the eponymous heroine: a 12-year-old actress named Li Minghui.

To audiences today, the alignment of sex between performer and character seems natural. Yet for director Li Jinhui — Li Minghui’s father — the casting was a daring experiment, if not an entirely iconoclastic act, as the appearance of a female performer in her biological sex challenged centuries of tradition of male impersonation in Chinese theater.

In that tradition, all female characters onstage were played by men, and women were excluded from the world of drama. Unsurprisingly, almost from the instant the youthful Li Minghui stepped onto the stage sporting a modern haircut, she was dragged into a swirl of controversies. Cultural conservatives fiercely condemned her performances in “Ms. Orchid” and other musicals directed by her father as licentious. Yet to ordinary audiences, she was a pleasure to behold. Within a few years, the younger Li had become one of the most beloved stars in Shanghai across a range of media: first on the theatrical stage, then in musicals and on vinyl records, and finally on the silver screen.

When Li Minghui debuted in the early 1920s, traditional Chinese operas still dominated the entertainment world in Shanghai and across the country. Stars of Peking opera and Kun opera enjoyed immense fame and fortune — virtuosic male impersonators who purported to embody more “authentic” femininity than women.

In this context, Li’s career was revolutionary: her female form, skillful integration of modern-style dance and popular music, and cross-media performance in theater and cinema all heralded the birth of a different kind of star system — one that was in sync with Shanghai’s changing mediascape of the gramophone, dance hall, and sound cinema.

This new star system represented a radical departure from the male-centered stage of xiqu, which was based on native literary traditions, cultural heritage, and practices of apprenticeship. Instead, it was largely founded on the mediatized figures of female performers, who embodied both the physicality of the “new woman” heralded by the May Fourth Movement as well as the gendered attractions of an emerging media industry.

Li was the first and brightest star in this modern star system. As Shanghai embraced new media technologies, she became a pioneer. The images and voices of performers like Minghui were reproduced and consumed across multiple platforms — in films, on phonograph records, in print media, and on stage — producing an immersive celebrity culture that in many ways prefigures our experience of media saturation today.

The making of this system should largely be credited to Li Minghui’s father, Li Jinhui, who was both an avid entrepreneur and an impassioned advocate for cultural change. Sometimes called the founding father of Chinese popular music, Li Jinhui had a versatile career: he wrote children’s musicals, composed love songs, and established all-women song and dance troupes. He used Li Minghui’s stardom to recruit talented young girls to his art academy, collaborated with film studios, and developed a speed training system with a comprehensive curriculum of singing, dance, acting, foreign languages, and general knowledge. Many actresses who later lit up Shanghai’s silver screen, such as Wang Renmei and Zhou Xuan, started their careers in Li Jinhui’s art school and dance troupe.

Commercial motives aside, Li Jinhui strived to support his May Fourth contemporaries by introducing a new culture of performance that could simultaneously entertain and enlighten the public. Ironically, however, he was marginalized by the May Fourth vanguards and denounced for creating musical work that was decadent and of little artistic merit.

Indeed, Li Jinhui’s art was never as refined, grandiose, or politically concerned as that of May Fourth cultural elites like Lu Xun. Rather, it was characterized by wit, sensationalism, and the display of female bodies. One of the most acrimonious criticisms of Li’s work came from Lu Xun himself, who once compared Li’s song “Drizzle” to the cacophony produced by a hanged cat.

Nevertheless, despite the charges levied against them for promoting “licentious singing and lurid dancing,” Li Jinhui and Li Minghui accomplished things that were beyond the purview of their contemporary elite intellectuals. The emancipation of women had been on the agenda of the May Fourth reformers from the very beginning. Like Li Jinhui, they used theater to raise public awareness and disseminate messages of gender equality. But when the New Culturalists staged progressive dramas, like Henrik Ibsen’s “A Doll’s House” and Hu Shih’s “The Greatest Event in Life,” they invariably used all-male casts to perform stories of women’s liberation. On stage, female characters were allowed to step out of their homes and divorce their husbands, but women could not act out their own emancipation. The reformers wouldn’t budge on this until 1923, a year after Li Minghui’s 1922 debut undermined the taboo against female performers.

But even more significant than challenging centuries of theatrical conventions was how Li Minghui portrayed the ideal of the “new woman.” This new woman spoke and sang in the standard national language, expressed her genuine feelings of love and belonging, and revealed, with confidence and composure, a body that was modern, talented, and able. Her image was never too radical; instead, it was broadly accessible and often delightful. Li Minghui’s versatile performances across an array of media, from music theater to sound cinema, resonated with audiences in a way that the abstract, high-culture ideals envisaged by the era’s intellectuals could not.

It is important to note, however, that such transmedia representations of the “new woman” were not without their complexities and contradictions. Even as songstresses, the archetypical new women became central figures in Chinese popular culture, but the parts they were allowed to play often reinforced traditional gender roles. In many films, female singers were presented as passive objects to be sacrificed, rescued, or redeemed, and their exceptional talents often led to tragedy rather than empowerment. An example of this can be seen in the 1937 film “Lucky Money.” While it showcased the singing talents of Li Minghui, the narrative ultimately frames her voice as a source of misfortune rather than agency. This tension between the growing prominence of female performers and persistent social conservatism would continue to shape Chinese popular culture for decades to come.

Editors: Cai Yiwen; portrait artist: Zhou Zhen.

(Header image: Li Minghui on the cover of “The Young Companion” magazine, April 1926. Courtesy of Hao Yucong)