China’s Gen Z Finds an Unlikely New Hero: A Sad, Tired Brit

After weeks of grinding through 12-hour shifts and weekend overtime, Jack Forsdike was running on fumes. In January, he’d landed what seemed like the dream job as a video game designer at one of China’s leading tech companies. But this wasn’t fun anymore.

The company wanted to fast-track the release of a game Forsdike was working on, and the 27-year-old was under intense pressure. Most days, he wasn’t getting home until after 10 p.m. He hardly had any time to spend with his wife. Exercise was a distant memory.

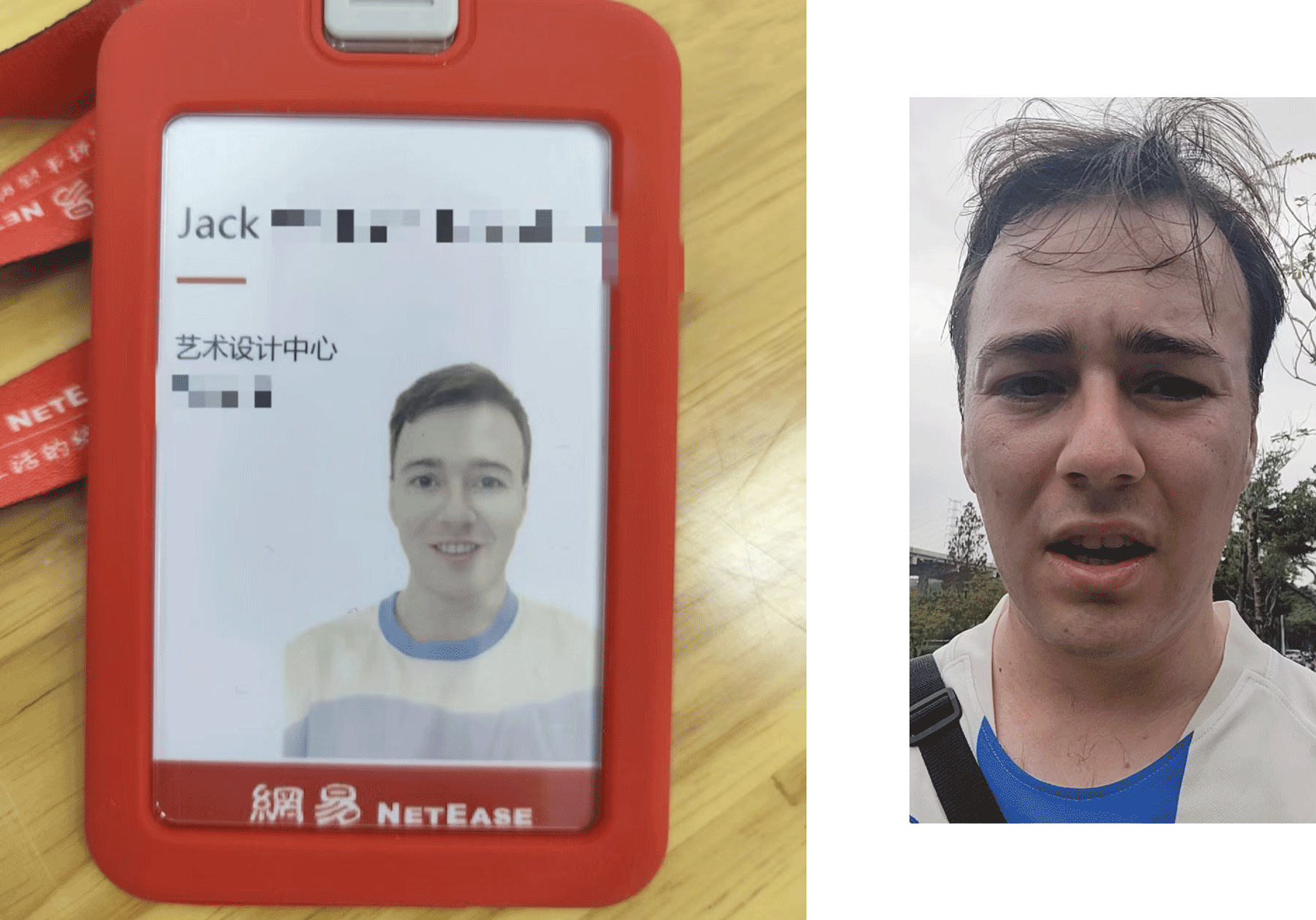

One April evening, Forsdike decided he needed to vent. He took a photo of himself looking utterly drained and posted it to his feed on the Chinese social platform Xiaohongshu. “Why did I come to China to work?” he asked, self-mockingly, in the caption.

The response caught Forsdike completely off guard. His Xiaohongshu feed exploded, racking up thousands of likes within days. When he moved on from the company two months later, things snowballed even more.

His post sharing his relief at regaining his freedom, which showed him sipping a coffee in a Hawaiian shirt, went even more viral. Memes spread like wildfire featuring the two photos of Forsdike side by side, labeled “after starting work” and “after resigning.”

By August, Forsdike’s account had received millions of views and tens of thousands of comments. Several major Chinese media outlets had run profiles on him. His story had even spread beyond the mainland, to news sites in Hong Kong and Taiwan.

“It was crazy,” Forsdike told Sixth Tone. “I had no idea it would get picked up so much.”

The Brit had been swept up by one of China’s most popular social media trends: the “naked resignation” movement, where quitting without a backup plan is almost a badge of honor.

It stems from mounting frustration with the “996” schedule — 9 a.m. to 9 p.m., six days a week — that dominates China’s tech industry, driving young workers to walk away from the relentless grind.

For years, workers tried to push back against the 996 work culture. The backlash became so intense in recent years that the Chinese authorities stepped in, launching campaigns against excessive overtime. But these efforts have only had limited success, with many employers continuing to insist on long hours behind closed doors.

That has left many young Chinese looking for a way out. On social media, stories of people ditching 996 roles to enjoy a slower pace of life — or “lie flat” — have become massively popular. Sometimes, the quitters already have another job lined up. But many simply leave without a backup plan, diving straight into “naked resignation.”

Forsdike’s story fascinated these disaffected tech workers. Many were amused to see a foreigner being beaten down by the 996 grind, and becoming a niuma — or “beast of burden” — like them.

“A foreigner came to China and became a foreign beast of burden,” one Xiaohongshu user quipped.

But for others, there was more to it than that. Many felt a real connection to Forsdike, saying that there was something poignant — even moving — about seeing the Chinese tech industry from an outsider’s perspective.

“There was a sense of empathy,” Forsdike said. “It also made me feel good that people felt the same way. When you’re in that kind of role, you’re never sure — is it just me that’s feeling like this?”

Into the fire

Forsdike was initially thrilled when he was offered a job by the tech giant NetEase. A native of Yorkshire in northern England, he had developed a love for China while studying for a modern languages degree at the University of Manchester.

Picking Chinese almost on a whim, he spent his year abroad studying in Beijing and loved every minute. After graduating in 2020, he began looking for ways to get back to China. But that wasn’t easy during the pandemic; several job openings fell through over visa issues.

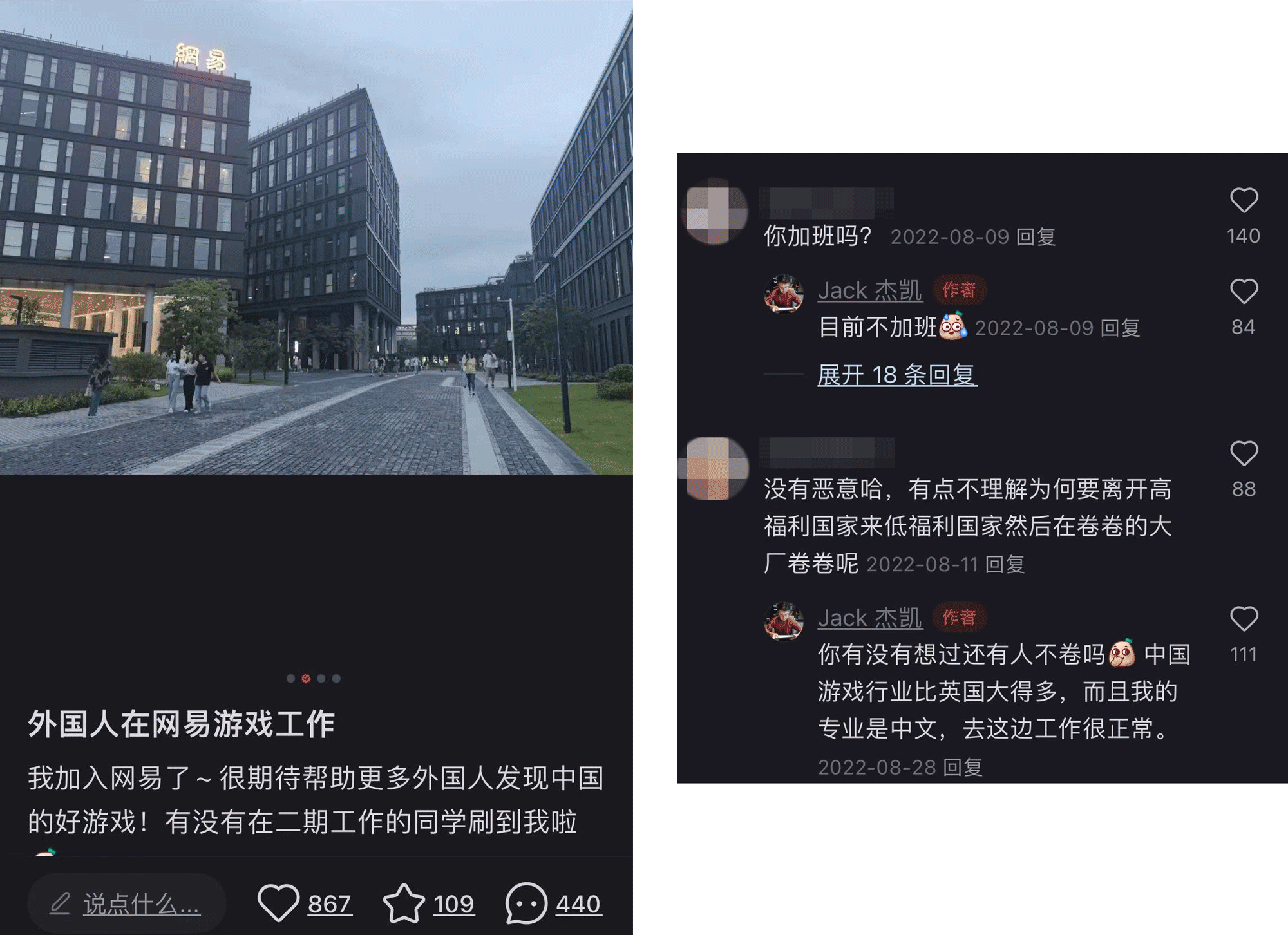

Finally, in mid-2022, NetEase managed to find a role for him at their office in the southern metropolis of Guangzhou. For Forsdike, it felt like an ideal gig. He’d been a gamer since his days playing Pokemon on his Nintendo Game Boy as a 6-year-old. And NetEase is a genuine powerhouse in the video games industry, producing the mobile version of Minecraft, among many other titles.

“I was really excited,” said Forsdike. “I was sure that I’d meet lots of interesting and talented people, and maybe get a chance to make a career in the games industry.”

The Brit was dimly aware of the Chinese tech industry’s reputation at that point, but he wasn’t too worried. He’d read that the government was clamping down on 996 schedules. And anyway, how bad could it be?

“Terms like 996 were just abstract concepts that I’d heard of, but I’d never actually seen before,” he said.

At first, everything went smoothly. The NetEase campus was beautiful. There were several excellent canteens, two gyms, and even a rooftop tennis court. And Forsdike was mostly enjoying his role. He was working as a translator, interpreting in meetings and polishing English documents. It wasn’t what he wanted to do long-term, but it was a foot in the door.

But it was after Forsdike got a transfer that things started to unravel.

At the start of 2024, he was given a role in the planning department. It was exactly what Forsdike had hoped to do. He was now in the core of NetEase’s business, contributing directly to developing its mobile games. That, however, meant he would also be under greater pressure.

Before he started his new position, human resources told him frankly that his new team was on a 996 schedule. The game they were developing was slated for release in six months, and everyone was working flat out. He would need to “adapt” to the long hours, they warned.

His new manager tried to make allowances for him, knowing foreigners often struggled to keep up. The Chinese staff were expected to be in the office until at least 9 p.m. during the week, and to work every Saturday. Forsdike only had to work late evenings and weekends if he had an urgent deadline to meet.

By April, however, there was always an urgent deadline to meet. With a big test run coming up, Forsdike was working even harder than most of his teammates. At one point, he worked 20 days consecutively, often finishing well after 9 p.m.

“No one ever said to me, you need to come in on Sunday as well,” he rued. “But if I hadn’t, my stuff wasn’t going to get finished. I wasn’t the only one. It was maybe 20% of the overall team.”

When the company decided to cut his role in June, Forsdike was relieved. He could have searched for another job within the company, but by that stage he wanted to leave anyway. He felt pale and heavy after weeks stuck in front of his computer. On Xiaohongshu, he told his followers: “My face is the shape of a potato.”

A new beginning

Forsdike never expected to become a social media star. He’d begun posting on Xiaohongshu during his year abroad, sharing little details from his life in Beijing. A few of these posts had done well, receiving a few hundred likes. But nothing prepared him for the response to his posts about leaving NetEase.

“I was getting a little bit of traffic before, so it wasn’t like I was talking to the void,” he said. “But it was just a fun hobby.”

For Forsdike, the reaction was ultimately a reflection of the depth of frustration among China’s tech workers. To many of his followers, it was validating to see a foreigner react with such horror to conditions inside the industry.

One comment Forsdike made in a domestic media interview in particular struck a chord. When asked whether he got used to the long hours at NetEase, he replied: “No, I didn’t get used to it. There are some things you shouldn’t get used to.” This quote was later shared by several commenters, receiving thousands of likes.

Forsdike often felt for his Chinese colleagues at NetEase. A few weeks working 996 had almost broken him, but many of them had endured similar schedules for years and expected to continue doing so for the foreseeable future. Most of the senior staff had families to support, and they couldn’t afford to quit.

“They often felt like wherever they go, they’d be working this hard unless they take a significant pay cut,” said Forsdike. “There was a sense of resignation. We would chat about it, people would complain a bit, but it’d usually end with them saying mei banfa (there’s no solution).”

In the short term, Forsdike knows that things are unlikely to change. With the economy slowing, Chinese employers have strong incentives to keep their workers under intense pressure. But he believes that the tech industry will eventually need to evolve.

At NetEase, managers said that the generation born after 2000 is more difficult to work with, according to Forsdike. And he understands why. To many of these fresh graduates, working in the tech industry doesn’t look like an attractive prospect.

“People work crazy hours, but there isn’t necessarily a big goal at the end. You often just work those hours because there’s nothing else, and then you can still very easily just get thrown away at the end,” said Forsdike.

Forsdike hopes that, in his small way, he can encourage more young people to avoid the 996 lifestyle. Ultimately, it’s just not worth it, he stressed.

“It’s not healthy,” said Forsdike. “People lose the chance to spend time on their hobbies. They lose the chance to have fun and meet new friends, or even get into a relationship and start a family. They lose the chance to do so many things in their lives because they feel completely drained by their work.”

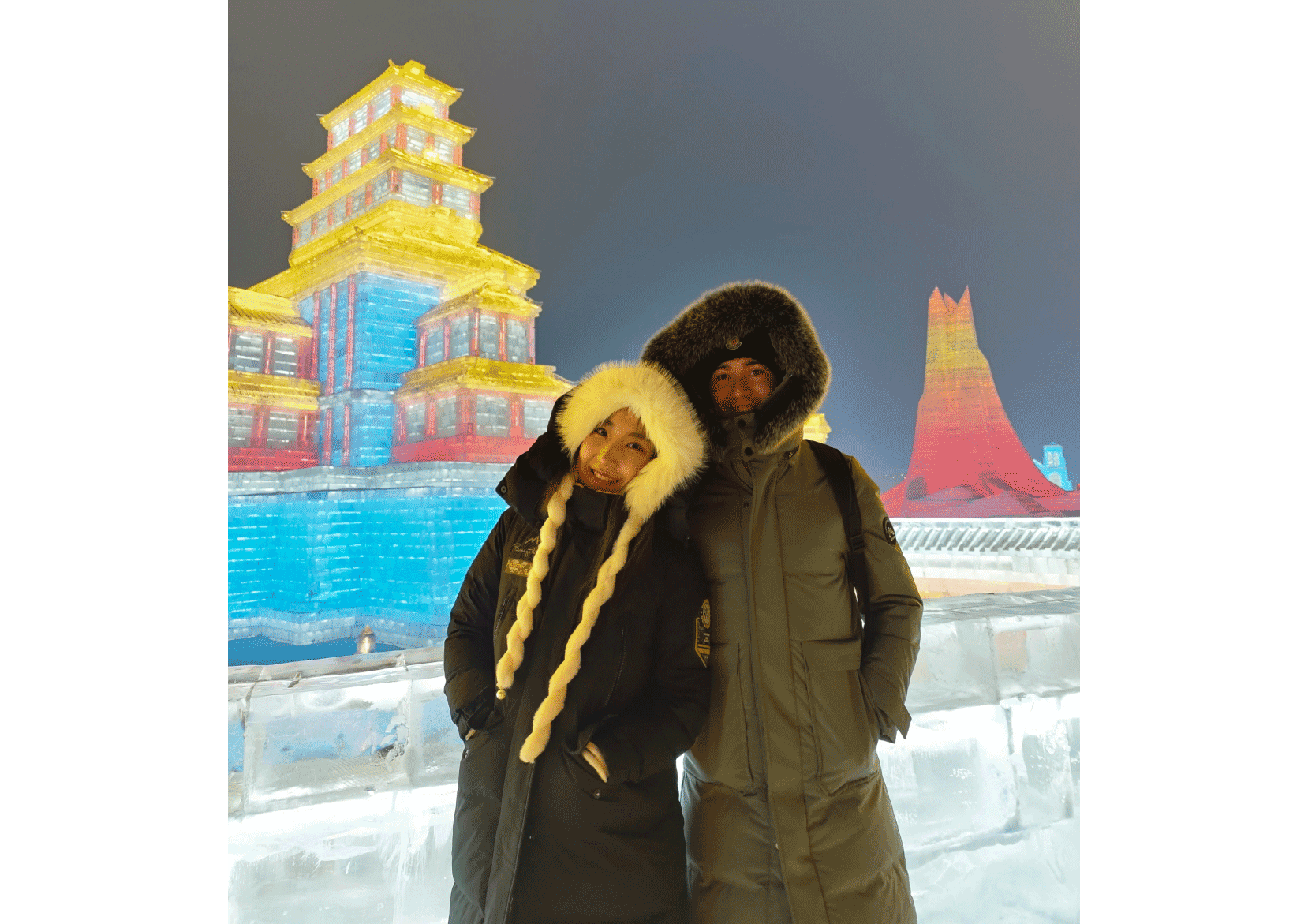

As for himself, Forsdike plans to take his own advice. He recently moved from Guangzhou to the northeastern city of Harbin. He plans to “lie flat” there for a while, spending time with his wife and pet dog. In December, the couple will fly to the U.K. for their first Christmas with Forsdike’s family.

After that, Forsdike isn’t sure what he’ll do. Despite everything, he said he missed working in the gaming industry and felt that “Overall, my time at NetEase was positive.” But would he ever go back? He paused a few seconds before answering.

“Yeah, I mean, that’s the question,” he said. “I never want to say never. I met a lot of fantastic people there, and I definitely learned a lot. But I’d have to be very sure about what the working culture in the team was like before I went back.”

Editor: Apurva.

(Header image: Visuals from @Jack 杰凯 on Xiaohongshu, reedited by Sixth Tone)