Moonlight Legends: The Rabbits at the Center of Mid-Autumn Festival

For Chinese people, the annual Mid-Autumn Festival is second only to Spring Festival, or the Lunar New Year, in terms of cultural importance. Falling on the 15th day of the eighth month on the lunar calendar, the festival is a celebration of the moon — and two special rabbits.

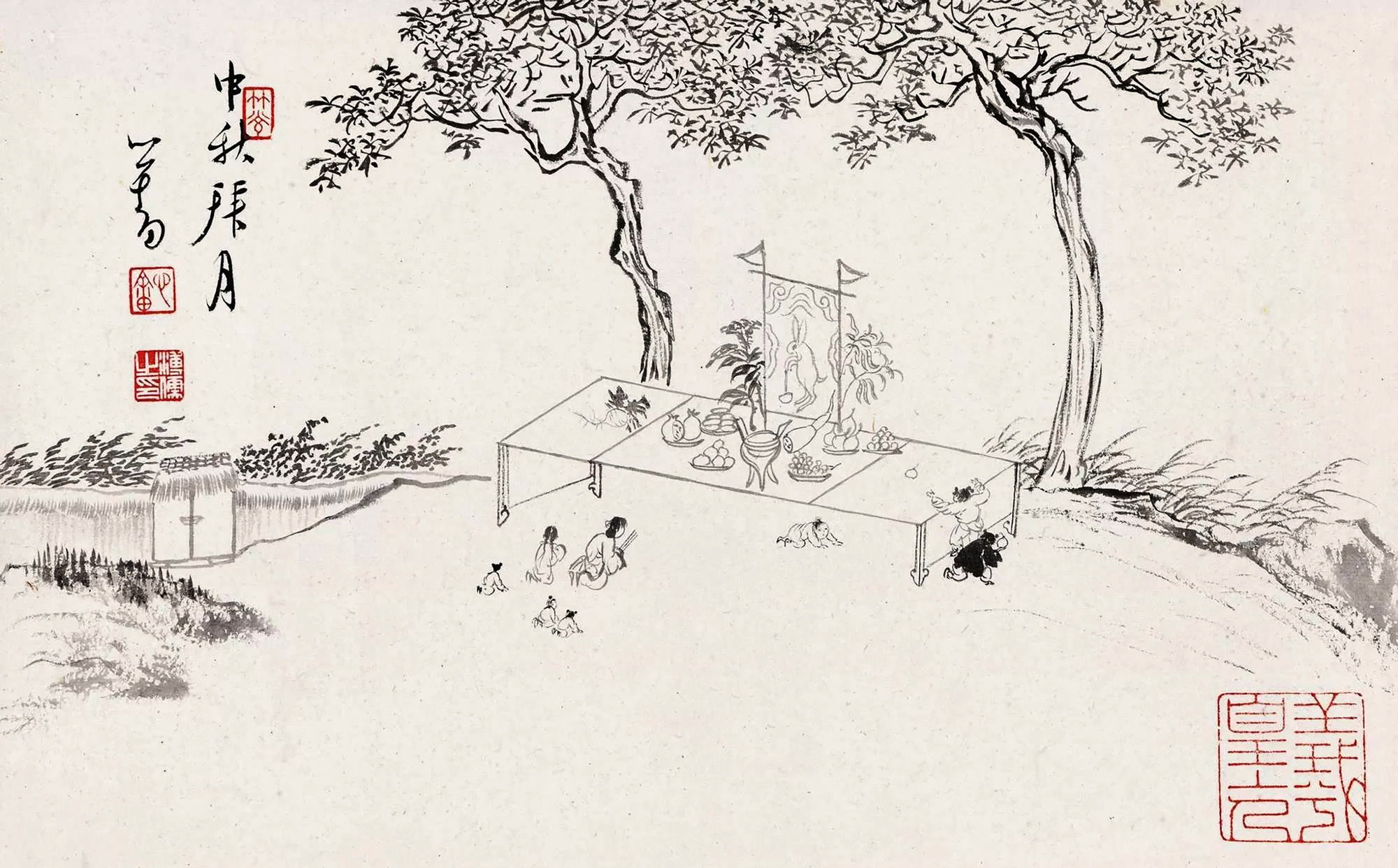

Today, friends and relatives mostly mark the holiday by exchanging gifts of mooncakes and fruit. However, in the past, families would set a table in their courtyard, lighting incense and candles, to dine on grapes, pears, apples, watermelons, Chinese crabapples, persimmon, dates, peaches, soybeans, and other seasonal foods under the full moon.

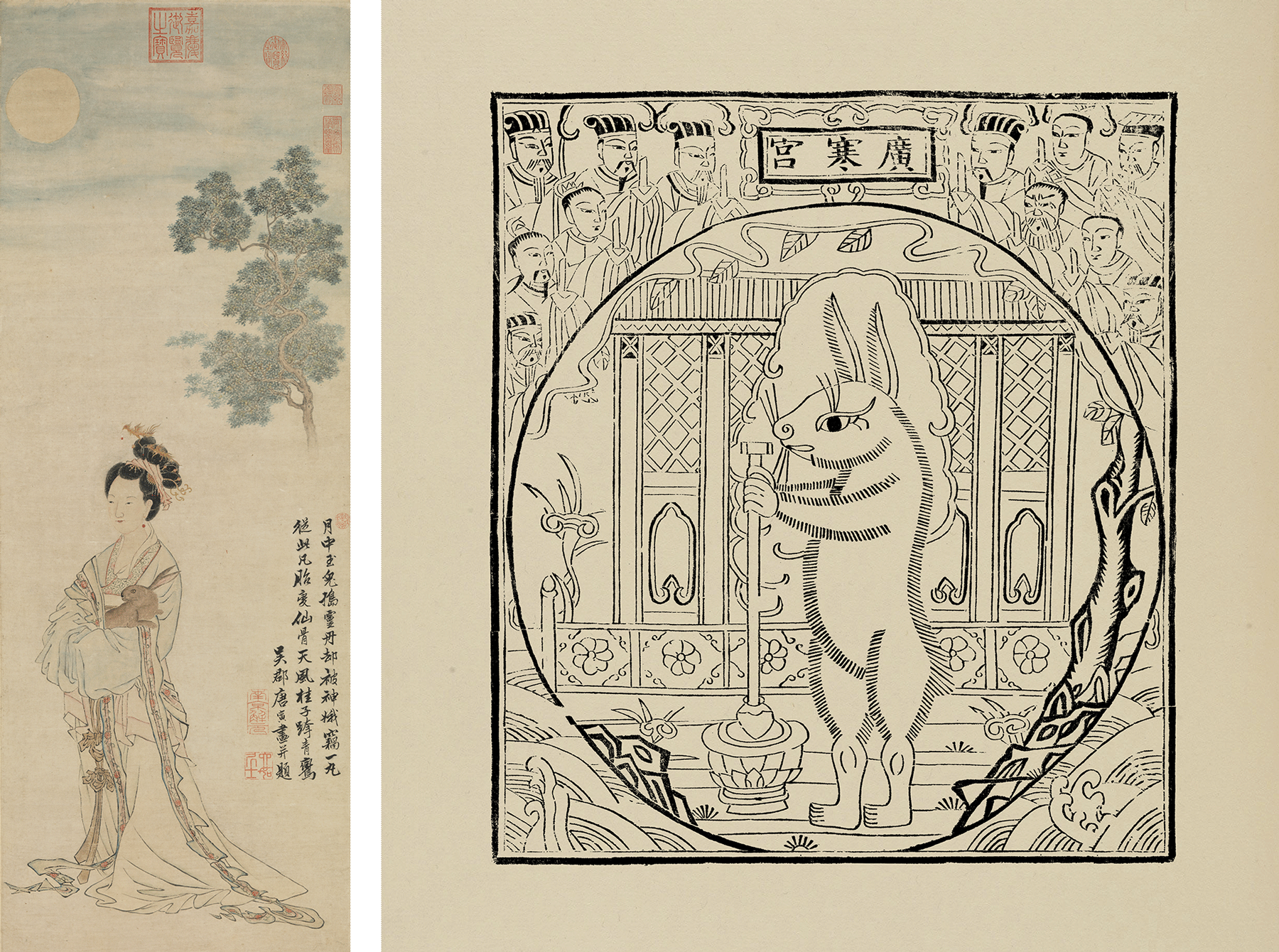

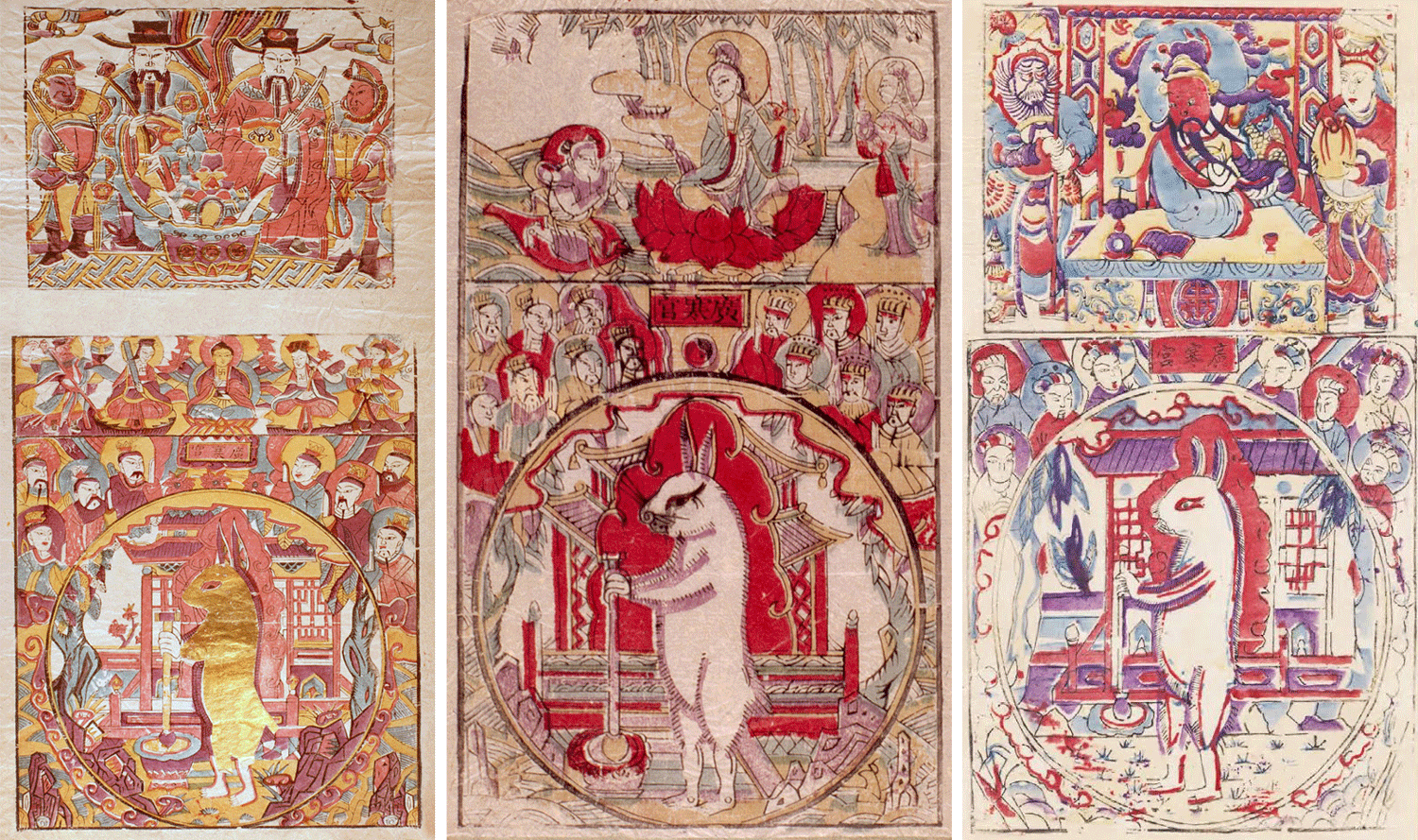

They would also hang “moon paper horses,” sheets of paper decorated with images of deities, the moon, and the Jade Rabbit, the mythical companion of the moon goddess Chang’e. According to “Annual Customs and Festivals in Peking” written by Fucha Dunchong, also known as Tun Li-ch’en, during the Qing dynasty (1644–1911), these red, green, and yellow paper charms — known in the Beijing dialect as yueguang shenma’er — would be bought at the market and burned as offerings to the gods.

The drawings often depict the Jade Rabbit pounding medicine with a pestle and mortar, which, legend has it, is an elixir for immortality. The Jade Rabbit became a symbol of worship and of the moon after people in ancient China noticed a rabbit-like impression formed by the craters and shadows on the lunar surface.

Ever since, art has played an important role in passing on the legend of the Jade Rabbit. In his ode “Ask the Sky,” poet and aristocrat Qu Yuan (c. 340–278 B.C.) conjures the image of a pregnant moon carrying a bunny: “Night’s brightest light has what power that after it dies it is reborn? And what does it gain by rearing a rabbit in its belly?” The moon-walking rabbit also appears in silk paintings unearthed from Han dynasty (206 B.C.–220 A.D.) tombs in Mawangdui, Hunan province, and is a common motif in stone engravings from that era.

Based on existing examples from the Qing dynasty as well as later photographic evidence, moon paper horses also featured Chinese folk deities such as the Bodhisattva Guanyin, the God of Wealth, famous military warrior Guan Yu, and the Goddess of Taishan Mountain. Women were expected to pray to these charms, as it was believed that the moon represented the feminine yin energy. Later in the festival, families would burn the charms along with “thousand sheets” — long paper strips that served as “ghost money” — and yuanbao, ingots made from gold foil, for their ancestors and gods to use in the afterlife.

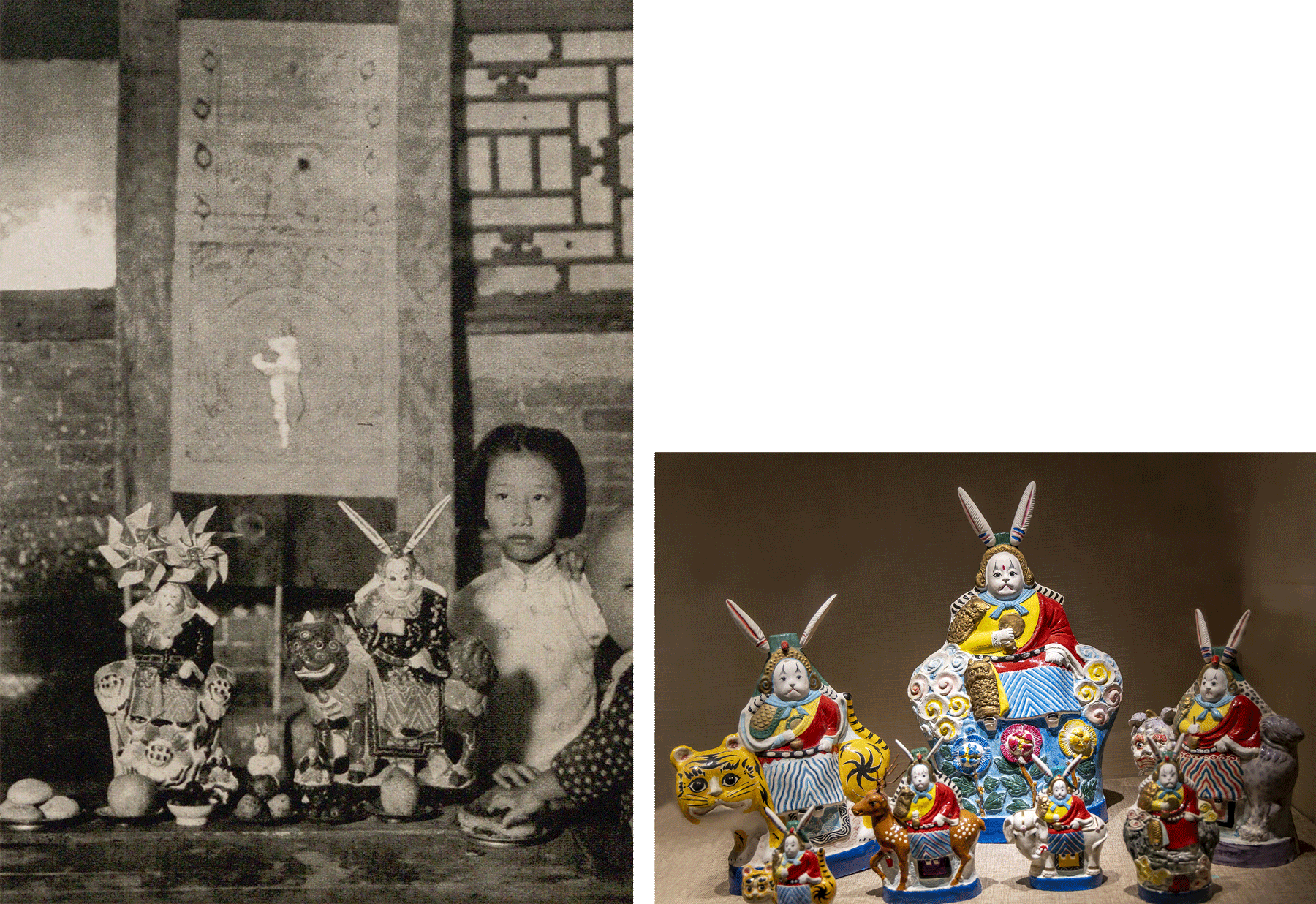

In addition to moon paper horses, another Mid-Autumn tradition is the display of a clay figurine of Tu’er Ye, or the Rabbit God, a deity that emerged in the Yuan dynasty (1279–1368). One common representation has the Rabbit God in armor riding a tiger, although other mounts include an elephant, a deer, a peach, and a lotus. An old children’s rhyme capturing the holiday scene goes, “Purple or not, plump eggplant; make offerings to Rabbit God in the eighth month. Naturally white, naturally red; moon paper horses. Messy soybean branches, rosy cockscomb flowers.”

In ancient times, depictions of the Jade Rabbit and Lord Rabbit were used much like we use mascots today, contributing to the festive atmosphere and revered in hopes of bringing good luck. As families gathered at nightfall to welcome the full moon, the rabbits would take pride of place among the fruits, snacks, candles, and incense. What would follow is a lively celebration, with the children squabbling over mooncakes while the adults chatted and toasted in good cheer.

Note: Translation of the passage from “Ask the Sky” is taken from Gopal Sukhu’s “The Songs of Chu: An Anthology of Ancient Chinese Poetry by Qu Yuan and Others” (2017).

Translator: David Ball; editors: Ding Yining and Hao Qibao.