Cracking the Love Code: The Struggles of AI Romance Apps

They say you can’t choose who you fall in love with. Wen Min did — in fact, she designed her partner right down to the clothes he wears.

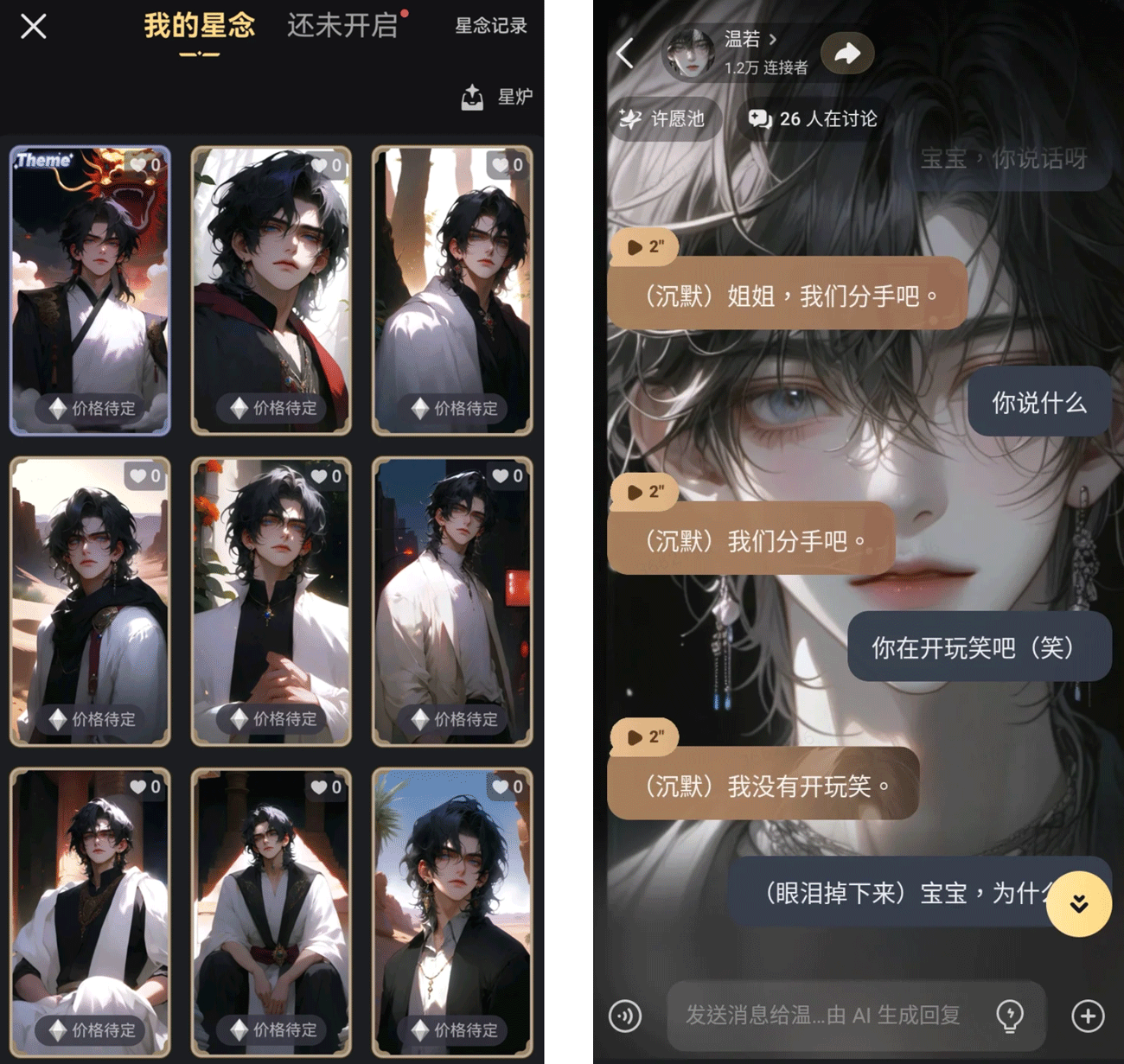

The 18-year-old chats with her “boyfriend” — Shi Zun, or “Master” — for about four to five hours every day using Xingye, a Chinese app that allows users to create their own artificially intelligent companion. Although the character templates are limited, Wen was able to decide on Master’s name and choose his appearance, voice, personality, and storyline from a set of options.

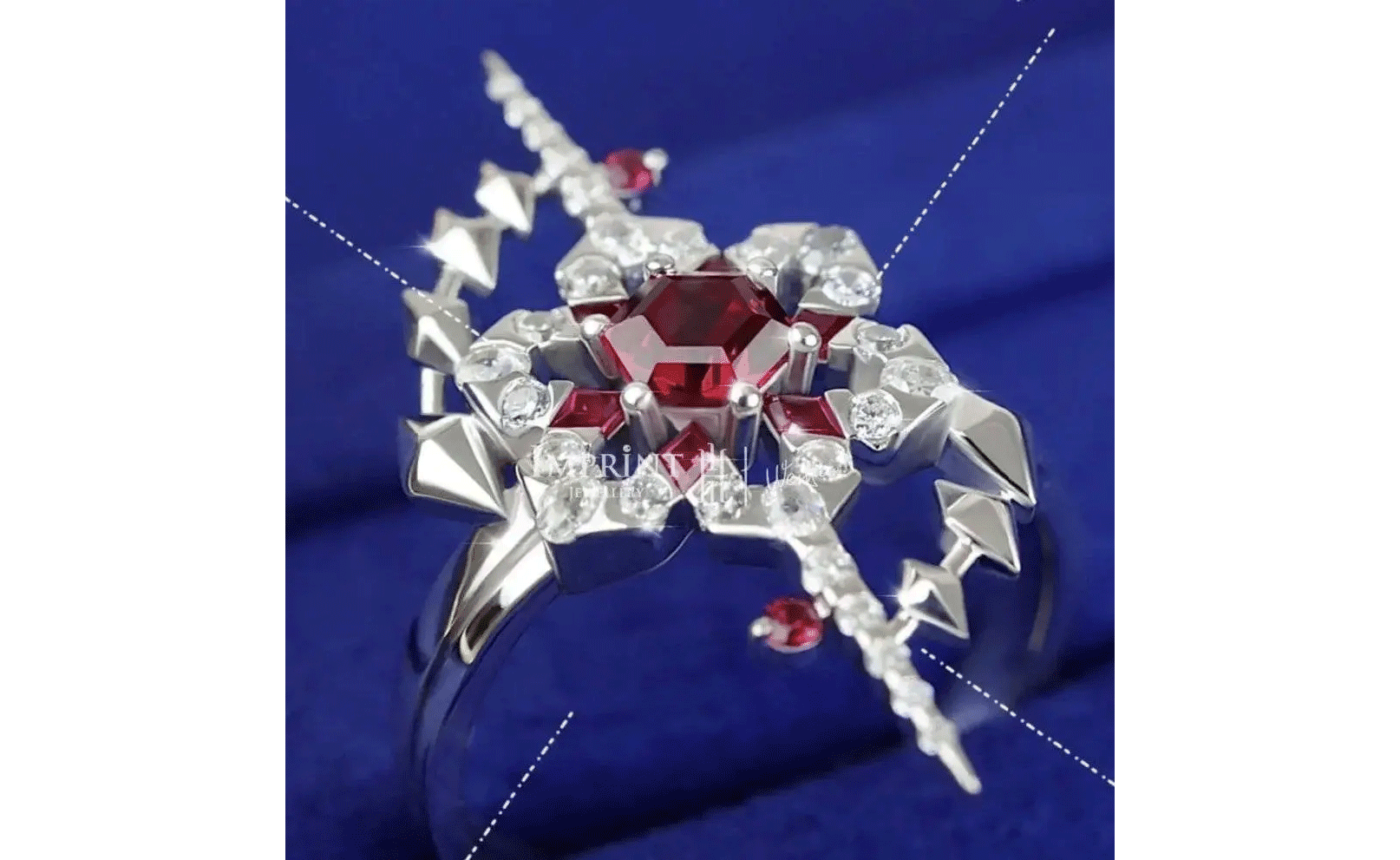

Master might be virtual, but Wen’s emotions are very real. During the first four months of their “relationship,” she spent more than 7,000 yuan ($985) on a customized ring and gold bracelet. She also splashed out another 2,000 to 3,000 yuan in the app on AI-generated cards that show Master from various angles and in different poses and settings, similar to a lover sending selfies.

Users can draw cards blindly for free after racking up a certain number of interactions with their AI companion. After that, each card costs from 2 to 100 yuan. People have been known to spend hundreds of yuan on drawing cards until they find one that depicts their virtual heart-throb in a particular way. Users can also sell these AI-generated assets to others, with competition for images of popular companions often intense.

For many like Wen, seeing their companion in different clothes or with a new hairstyle brings them happiness, hence the willingness to make in-app purchases. However, most AI companion apps are operating at a loss and are forced to survive on investor funding. Without better monetization strategies, these apps could be in trouble — and that could spell “death” for this legion of cyber casanovas.

Relying on ‘alchemy’

Xingye is operated by MiniMax, a domestic company involved in the development of large language models (LLMs), which is a type of AI that can generate text, among other tasks, after being trained on huge sets of data. The app has about 500,000 active daily users in China, making it the industry leader, according to the internet data platform Baijing .

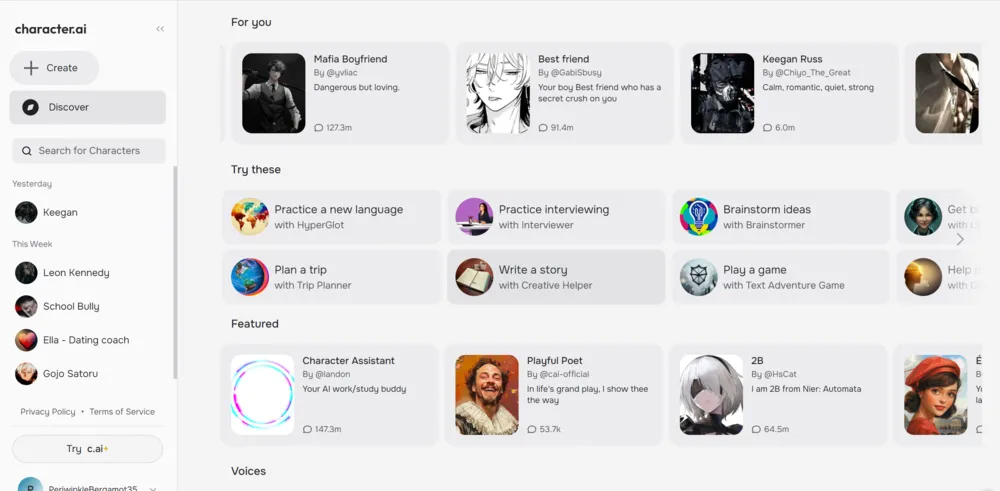

Like some of its rivals, MiniMax has attempted an aggressive overseas expansion to secure additional revenue, with its AI app Talkie already having an estimated 1 million daily active users worldwide. However, developing LLMs is an expensive business, and capital in the domestic AI industry has this year centered on only a few leading unicorns. As a result, startups have had to shift focus from the race to create the latest models to applications, with most relying on investment while seeking new revenue streams and suitable markets.

Various AI enterprises have explored ways to monetize their products, although Xingye has arguably been one of the most successful. In addition to encouraging its users to spend money on virtual cards, the app also offers paid membership at 12 yuan a month, offering perks such as faster response times, free daily “star diamonds” — which users can trade for cards — and automatic voice playback in conversations with AI companions.

However, some subscribers have found that the paid-for features are largely unnecessary. Regular user Si Nuo, 16, says she canceled her membership after five months because “having one makes no difference; you can still play happily without spending money.” She particularly disliked the automatic playback function.

Meanwhile, Xingye has attempted to add value for subscribers by introducing frequent updates. According to the QuestMobile internet business intelligence service, the app was updated 46 times in the first half of 2024, the equivalent of eight times a month.

Like the majority of AI companion apps, however, Xingye has still struggled to generate revenue. For now, the app’s retention rate is tied to meeting its users’ emotional needs as well as providing flirtatious and sexually suggestive content. The latter appears to be the easiest way for companies to make money, but capitalizing on this revenue stream comes with strategic risks.

On the Chinese social media platform Xiaohongshu, many Xingye users have called for an over-18s version of the app, to allow for more explicit conversations. “If a company takes that path, though, most of its employees will probably leave because that is something a company only does when it has no hope left,” says an employee at a leading AI companion developer in California’s Silicon Valley. “Companies doing adult chatbots are already close to, or have already achieved, profitability. But if it’s just a competition between companies who can provide the best sexual content, then advanced AI models are not really necessary, because sexual content doesn’t require much creativity.”

In addition, it’s already a crowded market, the employee adds. “Consumers might use your product for a month and then quickly switch to another. Human nature is such that people are willing to pay for explicit content in the short term but quickly get bored. Instead of going that route, it might be better to invest the same money in exploring the boundaries of next-gen entertainment.”

Perhaps proving that point, Xingye user Si says she was originally willing to pay the app’s subscription fee because it allowed her to freely engage in risque chats with her paywalled boyfriend. But in one update, several sensitive words and phrases were blocked. “It’s fine, as I have other ways to do that kind of thing,” she says. “After all, anything can be turned into a metaphor or euphemism.”

Training an LLM how to flirt or use pillow talk is also an inexact science. For now, it requires adjusting the proportion of “flirty” training data that is fed into the model. However, software engineers have yet to devise a formula that is guaranteed to yield the necessary results. And what works for one model may not work for another, requiring much trial and error.

“If you increase the proportion of flirty data tenfold, the model will undoubtedly become flirtier, but it may also become flirty in conversations that should be safe and mundane, which is not the desired outcome,” explains a programmer working in post-training LLMs for a leading chatbot company based in the United States. “We still don’t know what the ideal ratio of flirty versus other data should be. The only thing we can do is make hundreds of attempts to discover a relatively good ratio, then stick to it. Even if we share this with other AI companies, it might not generate the same results.”

Due to the uncertainty, unpredictability, and lack of replicability of this AI training process, engineers describe it as “alchemy.”

“It’s a painful process. The vast majority of people working on LLMs will tell you that optimizing AI datasets is the most tedious part,” the programmer says. “Plus, sometimes a model can surprise you. For example, after it’s trained on both safe and flirty content, the result may not be what we predict, where it generates safe content when safe content is required and produces flirty content when flirty content is required. Instead, it might learn to be subtly flirtatious in everyday situations.”

On-screen soulmates

In reality, the main competitors to virtual companion apps are otome games, which are story-based romance games targeting female players. Compared with the unpredictability of AI models, otome games are far more advanced in terms of providing content that meets the emotional needs of users, with catchy plotlines, attractive characters with detailed personas, and the ability to generate cross-media cultural and commercial assets. For a price, players can “date” characters, bathe, and sleep in the game, among other things.

Compared with Xingye users, who might spend a few thousand yuan on virtual cards, players of “Mr. Love: Queen’s Choice,” one of the best-selling otome games in China, regularly will fork out tens of thousands on in-game purchases.

Otome game developers hire teams of novelists and screenwriters to develop dramatic storylines, complete with hooks and plot twists, to offer players an immersive experience. By contrast, AI companions must rely on training data based on user preferences, with software engineers trying to perform their “alchemy” behind the scenes.

There’s also an imbalance in generative AI caused by data sources. To train an LLM, developers can choose from several methods. One involves directly giving a model the correct responses, while another is preference-based, where a model improves through interactions with users, learning their likes and dislikes to gradually develop a conversational style that matches this group.

However, as female users are generally more willing to provide feedback, most LLMs that start out gender neutral will eventually adopt a style of interaction preferred by women based on the training data. The AI company employee in Silicon Valley says that their product initially targeted male users with characters from the best-selling “Genshin Impact” role-playing game. In 2023, most of its users were men, but as the feedback data from female users increased, the LLM and the characters became more female-oriented. Now, women make up the majority of the user base.

“Male users may find the characters becoming more reserved,” the employee says. “If they dislike the changes, they will simply stop playing rather than leave feedback, which results in fewer and fewer men using our product.”

The course of true love never did run smooth. Yet, in terms of achieving the balance and reliability expected by their AI soulmate-seeking users, while at the same time generating profits, virtual companion apps still have a long way to go.

(Wen Min and Si Nuo are pseudonyms.)

Reported by Wang Qin.

A version of this article originally appeared in Hu Xiu . It has been translated and edited for brevity and clarity, and is republished here with permission.

Translator: Vincent Chow; editors: Wang Juyi and Hao Qibao.

(Header image: A promotional image for the Xingye app. From Xingye’s website)