Throwing Shapes: The Rave Experience for Deaf Clubbers

Editor’s Note: BassBath is an inclusive clubbing experience in Shanghai in which mid- and low-frequency music is played throughout, allowing Deaf partygoers of all ages to enjoy the rhythm and energy through powerful vibrations. Here, one of BassBath’s organizers, Ding Jiayue — aka Pang Ding — discusses the people and ideas that inspired this project.

One night two years ago, I had just finished manning a secondhand goods stall at a flea market with my friend Eva, an artist who was learning sign language. We were at a restaurant eating and moving our hands, trying to use body language to talk to Hu Xiaoshu, aka Alice, a friend we’d just met who is deaf. From the start, I felt that Alice’s enthusiasm and lively spirit were infectious. She skillfully answered every “stupid question” that I asked from the perspective of someone who is hearing. She told me that when she was a child, as she couldn’t hear, even her dreams were silent.

Not long after, Alice reached out to say that an elderly deaf woman had seen a post of us at the flea market on the instant messaging app WeChat and that she had liked my crossbody bag. That’s how I came to know Grandma Hu. The first time we were introduced, Grandma Hu noticed my necklace and asked me where I’d bought it. Then, her gaze moved to my tattoos. “Pretty!” she exclaimed in sign language, her face full of excitement. She inspected every single tattoo on my body as though she were treasure hunting, then in total seriousness took out a wad of cash from her wallet and asked me to take her to get a tattoo. “We’re going tomorrow,” she signed.

After that, the two of us would occasionally get together. I would take handcrafted materials to her house and we’d string beads to make necklaces. She would take out paper and pens (for us to communicate), and then there were the desserts, candies, orange juice, and the rest. Gradually, I learned a few simple words in sign language, and Grandma Hu would put all kinds of temporary tattoos on her body. When I was with her, I saw both her fun personality, as well as how the social context she was in as a deaf elder manifested in subtle, daily difficulties. This experience deepened my desire to learn sign language, and to create larger spaces for the Deaf and hearing to meet and connect. I talked with a like-minded friend, Vis — an artist, bartender, and student of traditional Chinese medicine — and we decided to organize an activity together.

Vis and I have a curatorial committee called Transparent Afternoon, through which we eventually came to make more Deaf friends. Being with them, we realized that society lacks places for deaf and hearing people to really be together on a deeper level. The hearing world often holds an unequal gaze toward deaf people, be it prejudice or pity, yet there is no way to truly understand the inequality Deaf people face in society or understand all the hard work that goes into protecting their fundamental rights. However, the first step in breaking down prejudice often is creating connections among people. Only by truly “seeing each other concretely” can we eliminate labels and create the possibility of equality.

In the summer of 2023, at the Shanghai techno club All, Vis, Eva, and I tried to explore the relationship between signs and “taboos.” During the daytime, we created a pitch-black dance floor: the rules were that everyone could talk in the dark, but as soon as the lights went on, we could use only body language to communicate. In the process of all this, we thought of how love and connection have always been a part of the culture of the underground rave scene. We also thought about how sound is swallowed by the vibrations of speakers, as well as the visuals of light and shadow, and how there’s a chilled, intimate vibe in clubs. Maybe we could organize an inclusive rave event, we thought.

So, Vis and I started to plan an activity. Eva helped from afar, as she was studying in the Netherlands, by introducing the project to other groups that might want to collaborate with us. However, as hearing people fundamentally have a different perspective and can often take things for granted, from the start we knew that we needed deaf co-organizers. We reached out to Alice and invited her to join the project.

Alice is an artist and activist with enormous experience and leadership ability. She has devoted many years to the protection of Deaf rights and raising awareness about diversity. After returning from living in Austria for several years, she realized that the “Deaf cultural ecosystem” in China was often overseen by hearing people. For this reason, Alice took on the philosophy “Nothing about us without us,” emphasizing the need for people with disabilities to be involved in steering activities, narratives, and programs that touch on disabled culture. Alice brought with her so many experiences and ideas about inclusive programming, and even came up with the witty name BassBath.

Moving to the beat

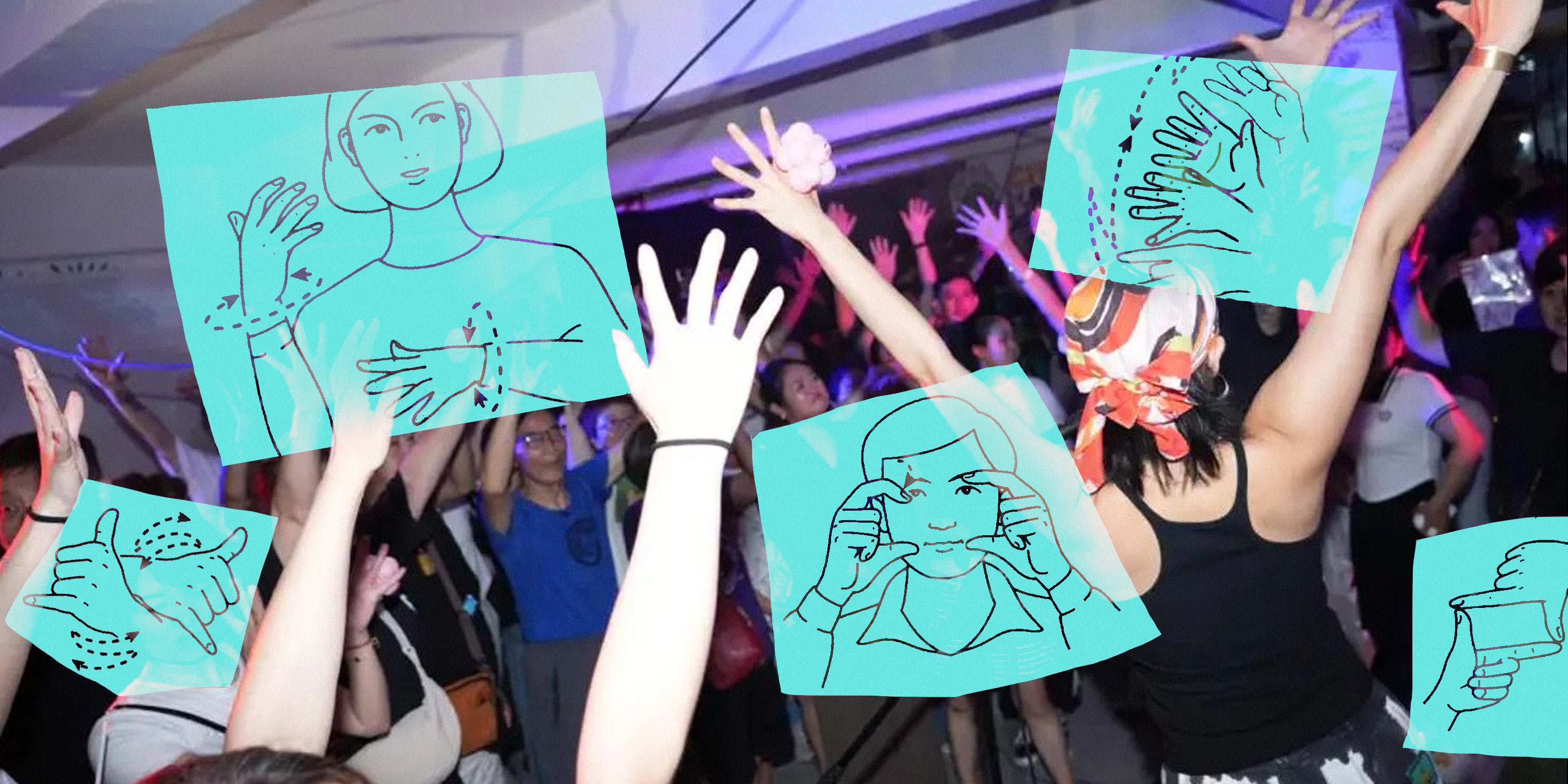

The first event took place at Shanghai’s Heim club in May. At the bar was a video screen playing the drinks menu in sign language, which also explained how to silently order a gin and tonic. The corridor walls also had rows of sign language posters. Alice took to the stage beneath bright, colorful lights, along with sign-language translator Tang Wenyan and emcee Jaymee, and they began directing the partygoers on how to play an inclusive ice-breaker.

Gradually, people formed a circle and began a dance battle. Xu Min, a deaf rapper, also performed two songs in sign language, followed by DJ sets. The biggest difference between BassBath and other clubbing experiences is that mid- and low- frequency music is played all night, using deep sounds to create somatosensory vibrations. Everyone “applauded” by gyrating their hands — sign for clapping — and danced to the music. The borders of language slowly began to merge.

In June, BassBath moved to an underground location along the city’s Xinhua Road. At first, the partygoers used sign language to bargain at the outdoor flea market, then after a while people moved indoors to the dance floor to listen to Alice, who was emceeing from a tall platform. Some squeezed into the front row to follow along with the movements of dancer Jiamin; others were more interested in watching a performance by X-90dB, a troupe of deaf dancers. Some people were so excited and began signing so fast that they accidentally dropped the drinks they’d just bought.

Away from the dance floor, many people were sitting around chatting, using their limbs, voices, facial expressions, and phone screens to communicate. People discussed many topics, from astrology and daily life to how their “identities” make for different life experiences. Some learned their first words in sign language and made their first deaf friends. Some of the deaf partygoers told us that it was their first rave, or at least their first rave that had felt “intimate” or “comfortable.”

Harmony in motion

DJs Huizit and Rainsoft, who manned the decks at the first two BassBath events, found them a completely new and radical experience. Huizit says their only previous knowledge was based on videos of sign language translations at music festivals, which they’d found “so cool.” Before the events, they had talked with Vis and I about how deaf people need low-frequency and bass-heavy music to feel the vibrations, so Huizit had chosen a lot of low-frequency house and hip-hop, while Rainsoft gravitated more toward ambient and techno music. Huizit says that designing their set was a lot harder than usual, because there was no way to predict how deaf clubgoers would feel about the vibrations.

For both of these veteran DJs, BassBath was a completely new and radical experience. Huizit recalls, “Everyone was feeling the music and dancing, something that is actually pretty rare at clubs. I was so moved.” While Rainsoft, always a believer that everyone has the right to experience music, said, “Everyone forgot themselves when they immersed themselves in the music. The power of the dance floor came to me like a wave. It gave me a lot of power.”

Of course, Grandma Hu also came to our BassBath events. She showed no hesitation in joining everyone on the dance floor. She told me she felt “totally wild with joy,” and she didn’t want to go home. “I’d just wanted to keep having fun. Even with my back sweating like crazy, I wasn’t afraid of getting tired. I was so happy to meet so many new friends,” she said.

Grandma Hu lives life to the fullest. She possesses an infinite sense of curiosity and happiness. Sometimes, when she’s excitedly telling me about her life, or showing me pictures and videos of her dancing, or sign language education videos, I feel a sort of boundless expansion in my heart.

At each event, the BassBath team received a lot of valuable feedback and advice on which to reflect. Our original intention was to create a not-for-profit party; the BassBath team, the artists, the sign language interpreters, the DJs — we all did this out of love. We certainly didn’t expect that the activity would snowball, or that we would get invitations from all over the world. The attention we’ve received has really inspired us, and it’s made us aware that we have to take on more responsibility.

We believe in the importance of “things coming slowly.” A stable influence requires patient input and effort. We hope that BassBath will, like a seed, sprout and grow roots, allowing more people to understand “Deaf culture” and creating awareness about equality. This all requires time.

(Eva, Grandma Hu, Vis, Jaymee, Jiamin, Huizit, Rainsoft, PinkHand, and Qingqing are pseudonyms.)

As told by Ding Jiayue.

A version of this article was originally published via BIE. It has been translated and edited for brevity and clarity, and is republished here with permission.

Translator: Marianne Gunnarsson; editors: Wang Juyi and Hao Qibao.

(Header image: Visuals from Xiaoman, Pingfan, and @透明的下午 on WeChat, reedited by Ding Yining/Sixth Tone)