Journey of Ink: How Chinese Art Built a French Museum

“The Journey of Ink: Modern and Contemporary Chinese Paintings from the Musée Cernuschi” will be held at the Bund One Art Museum in Shanghai until Jan. 4. During his lifetime, Henri Cernuschi (1821–1896), the founder of the Musée Cernuschi, mainly collected bronzes, as well as porcelains and paintings. After his death, the museum continued to expand its collection of East Asian art, and in the 1950s, it built a platform for exchanges between Chinese and French artists.

The Musée Cernuschi collection is a veritable treasure trove dominated by ancient Chinese artworks including around 15,000 pieces of colored pottery from the Neolithic period, bronzes from the Shang (c. 1600–1046 BC) and Zhou (1046–256 BC) dynasties, painted stones and sculptures from the Qin (221–206 BC) and Han (206 BC–AD 220) dynasties, colored sculptures from the Sui (581–618) and Tang (618–907) dynasties, porcelains from the Song (960–1279) and Yuan (1279–1368) dynasties, and calligraphy and paintings from the Ming (1368–1644) and Qing (1644–1911) dynasties.

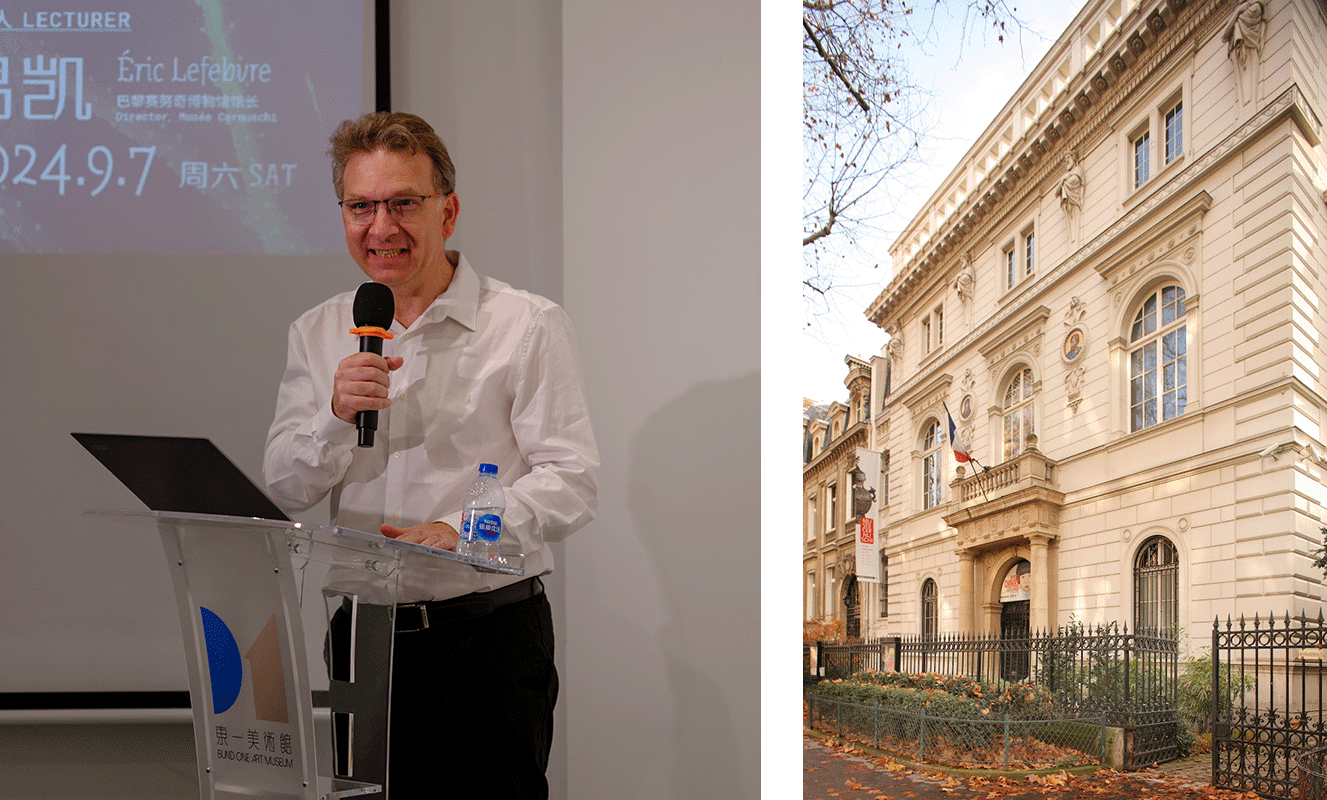

Ahead of the opening on Sept. 5, The Paper met with Eric Lefebvre, director of the Musée Cernuschi, to discuss its founder’s rich collection, the history of the museum, and its cultural exchanges with Chinese artists.

The Paper: The Musée Cernuschi houses Europe’s premier collection of Asian art. The founder, Henri Cernuschi, worked in banking and finance, and began collecting Eastern artworks under the influence of his friend Théodore Duret. Later, he focused on collecting bronzes from China and porcelains from Japan. Could you share with us the story of the museum’s founder?

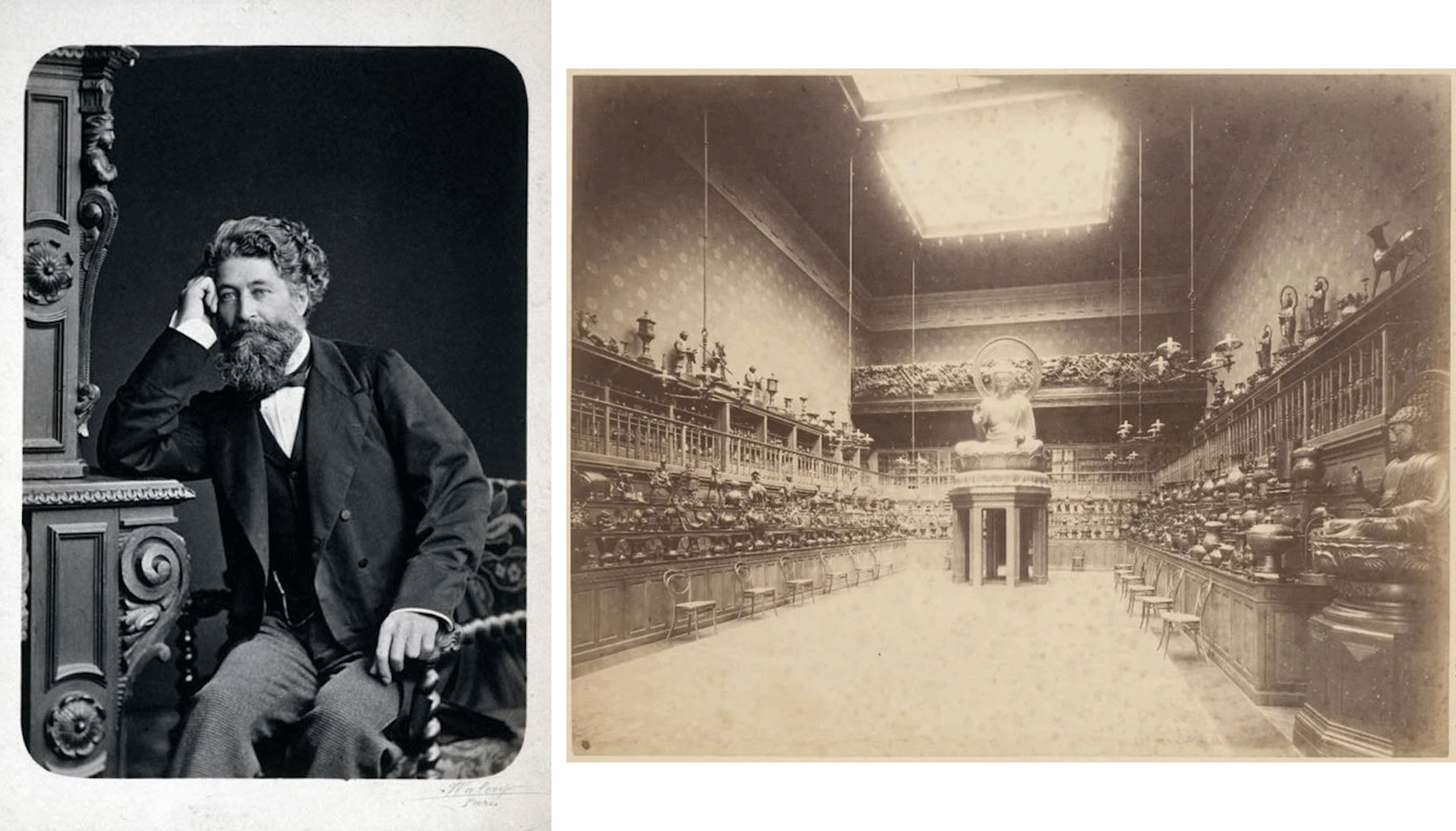

Lefebvre: The history of the Musée Cernuschi of course began with Henri Cernuschi. Cernuschi was born in Milan, northern Italy, where he grew up and studied. He was first known for his role in European politics. In 1848, Cernuschi participated in liberating Milan from Austrian occupation, and was elected as a parliamentary representative of the ephemeral Roman Republic (1848–1849). Later, he came to France, where he started a new life as an entrepreneur and got into finance. His career flourished and led to the founding in 1869 of the Banque de Paris, known today as BNP Paribas. Cernuschi was not only a politician but also an entrepreneur. Following the movement of La Commune de Paris, Cernuschi left Europe and traveled to Asia with his good friend Théodore Duret. This Asian journey was in fact a global journey, as they traveled first from Europe to the United States, then from there to Asia, and finally back to France.

Before that journey, Cernuschi had not been a collector of Asian art, but he was interested in art and archaeological discoveries. Japan was his first stop in Asia. He decided to collect bronzes when he arrived, bucking the established European trend. Previous European collectors had only focused on Chinese porcelain and Japanese lacquer; bronzes were an undiscovered category.

As well as starting a large collection of Japanese bronzes, Cernuschi also began a systematic collection of bronzes from the Shang to the Qing dynasty when he arrived in China, finding that its bronzes had a much longer history. He aimed to introduce the history of Chinese bronzes to audiences in Europe. After collecting Chinese and Japanese artifacts, Cernuschi did not continue to collect heritage conservations from other Asian countries. His behavior changed the trend in the West — which at that time focused on Chinese porcelain — with focus shifting to Chinese ancient artifacts, especially from the Shang and Zhou dynasties, which also influenced the identity and development of our museum for more than 100 years. Today, the Musée Cernuschi has a larger scope — for instance, artifacts from Vietnam — yet it is still dominated by East Asian artifacts.

Let’s go back to the establishment of the museum. Cernuschi returned to France, and a few months later, he curated a sizable exhibition at the Palais de l’Industrie, the venue created for the 1855 Paris Exposition. The impact of this exhibition was huge. Before the exhibition even closed, he had bought a plot of land in the neighborhood to establish the Musée Cernuschi. It was the first time that someone had purchased a specific space for the purpose of displaying Asian artworks.

The Paper: It’s said that Henri Cernuschi spoke no Chinese, so how was he able to collect those artifacts in China?

Lefebvre: Cernuschi didn’t know Chinese at all, and at that time there were no translated books related to bronzes in the West. He mostly relied on his own aesthetics, while often consulting and discussing with native Chinese enthusiasts through interpreters. He was born in Italy, affected by the Renaissance, and when he arrived in China, he decided to collect Chinese bronzes, doing that with the aesthetics and perspective of a Chinese collector. He stressed the importance of inscriptions in collecting. He also purchased a lot of Chinese books, hoping to provide something useful for future experts and scholars. Therefore, Cernuschi was not just amassing a private collection, he already had the idea of establishing a museum. What he offered to future generations were not only artifacts but also historical documents.

The Paper: How many artifacts are today in the collection of the Musée Cernuschi? And what are the most important pieces?

Lefebvre: With the expansion of the museum’s collection, we now have 15,000 artifacts. La Tigresse (a you, or vase), designed to contain fermented beverages from the Shang dynasty, is indisputably the most famous work of the Musée Cernuschi. It was collected by Henri Cernuschi in 1920.

The Paper: The “Journey of Ink” exhibition in Shanghai features many Chinese paintings, most of which were donated to your museum by the Chinese diplomat and art collector Guo Youshou (1901–1978). Could you tell us about the connection between the museum and the Chinese artists and cultural figures living in Paris in the period after World War II?

Lefebvre: Compared with Henri Cernuschi’s collection of bronzes and porcelains, his collection of paintings is smaller, though he also displayed some Chinese paintings in the Musée Cernuschi. Actually, he had a special aesthetic for Chinese paintings, and he was fond of figure paintings, as well as the finger paintings of Gao Qipei. After Cernuschi’s death, the museum became the Asian Art Museum of the City of Paris and continued to develop. During that period, China saw many great archaeological discoveries, and many French scholars and audiences became enamored with the new findings, including jade and porcelain. At the same time, the museum was continuing to follow Herni Cernuschi’s interest by developing its collection of bronzes.

After World War II, the Musée Cernuschi opened a new space, which is the period that the “Journey of Ink” exhibition in Shanghai will introduce. The director of the museum at this stage was René Grousset, who wanted to create exchanges centered on East Asian culture. The end of the war marked the start of a new era, one bringing fresh hope, and the museum could focus more on contemporary art and establish exchanges with contemporary artists. In 1946, the Musée Cernuschi held “First Exhibition: Contemporary Chinese Painting,” which featured the most famous artists of the time including Qi Baishi and Fu Baoshi. In addition, there was another Chinese artist, Zhang Daqian, whose exhibition was larger and more influential, which also influenced the development of our museum.

The Paper: Can you share with us the key artworks in the “Journey of Ink” exhibition?

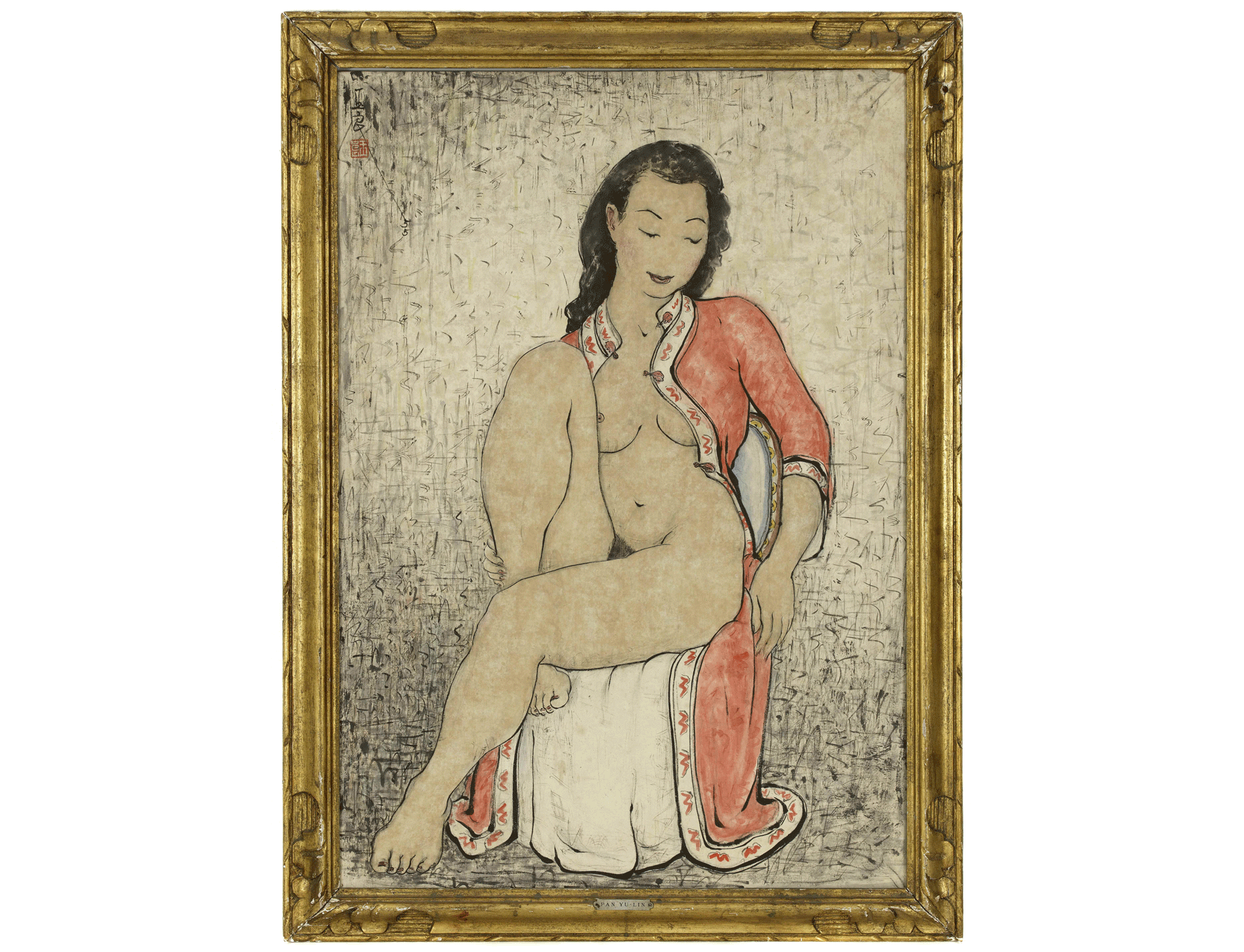

Lefebvre: There are early and mid-career artworks by Zhang Daqian in larger sizes, including portraits of his sponsors after returning from Dunhuang, as well as his large-sized ink lotus works. Another important artwork is Fu Baoshi’s “Dreamer.” Among the artists living in France, Pan Yuliang’s “Seated Nude with Red Qipao” is definitely a masterpiece. Besides, the work of Ding Xiongquan (Walasse Ting), whose paintings show that artists of this era were once again interested in ink painting. “One Hundred Layers of Ink” by Yang Jiecang also signaled an exploration of ink wash painting. Moreover, we display a number of video archives about painting.

The Paper: What motivated you to organize this exhibition? What do you hope that audiences will get from the experience?

Lefebvre: Since 1946, the Musée Cernuschi has been studying 20th- and 21st-century Chinese ink paintings. Unfortunately, we haven’t had the opportunity to introduce those findings to Chinese audiences. 2024 marks the 60th anniversary of the establishment of diplomatic relations between the People’s Republic of China and France, which is a great opportunity to introduce Chinese audiences to the collections of Guo Youshou, and the results of the exchanges that our museum has had with Chinese artists over the years. Moreover, the different histories and environments in which artworks have been collected also shape various collecting systems. We hope to share our understanding of Chinese ink paintings with audiences. From the 20th to the 21st century, ink painting has gone through consistent renewal, such as the introduction of concepts like “abstract ink” and “100 layers of ink.” We also want to share the art practices of those new concepts with Chinese audiences.

Reported by Lu Linhan.

A version of this article originally appeared in The Paper. It has been translated and edited for brevity and clarity, and is republished here with permission.

Translator: Eunice Ouyang; editors: Wang Juyi and Hao Qibao.

Sponsored content by Sixth Tone × Our Water.

(Header image: Details of “Scene at the Orchid Pavilion,” by Fu Baoshi. Collected by Musée Cernuschi)