Pointing Fingers: Exhibition Zooms In on Student Stress

Editor’s note: Qiao Fei’er, 18, began taking closeup photos of students’ middle fingers at her high school in Xi’an, the capital of China’s northwestern Shaanxi province. Rather than a statement of defiance, her focus was the “writer’s callus,” hardened skin around the knuckles caused by gripping a pen for long periods. The project eventually evolved into “The Body Being Shaped,” an exhibition in which Qiao reflects on the student experience at Chinese schools and on her own education.

Feng Xiao has a prominent callus on the top knuckle of her right middle finger. As she doesn’t use hand lotion, her fingers look dry and cracked, while the spot where her pen presses against the flesh is sunken and dark brown. “Stop taking pictures, it’s so ugly,” she tells her classmate Qiao Fei’er, who asked to photograph Feng’s finger for an art project. It’s the first time Feng has ever taken a close look at the middle finger on her writing hand. The finger of another student is even more deformed: The knuckle closest to the nail has shifted toward her index finger, leaving a gap when she closes her fingers. She says she plans to have surgery to correct it after taking the gaokao, China’s college entrance exams. She once tried using bandages to protect her fingers, but it affected her writing speed, so she stopped.

Qiao says that Feng was one of only a few people who were interested in participating in her project to photograph students’ middle fingers. Most others responded to her request by simply asking why. To recruit more subjects, she made a digital poster with the question in bold, “Why is that?” She wanted to get every student in her grade to discuss the relationship between the body and society. However, when she shared it online, the poster received a lot of likes, but no one signed up to be photographed.

At the time of the photoshoots, Qiao was taking a break from school. As she enjoys her freedom and creativity, she found herself unable to embrace the traditional exam-driven education system in China. Qiao especially disliked high school; she developed a fear of speaking when she was about 17 and frequently took time off because she could not stand being glued to a desk for more than 10 hours a day. In her final year, as textbooks piled up on desks and her classmates’ hunched backs resembled “rolling mountain peaks,” she began feeling lonely and depressed. After a heated argument with her parents, Qiao decided to take a leave of absence. Escaping the high-pressure environment of school made her feel as if she had stepped into a void, and she began to reflect on what she could do with her time.

It was at this point Qiao started to think about her deformed middle finger. She remembered a classmate in ninth grade who often complained about the swelling and ugliness of her “writer’s callus.” The classmate wrapped her finger and applied ointment, but it didn’t help. She later pressed as hard as she could on the bump to try to flatten it. It was a lightbulb moment for Qiao, and memories associated with her fingers came flooding back. She remembered how she did not like how her index and middle fingers would bend to the right after long writing sessions, so she would often try to straighten them by force. The callus on her finger was not big, but it still hurt after holding a pen for long periods, and Qiao would rub and massage the bump. She once showed her deformed finger to her mother, whose reaction was simply, “It’s not a big deal.” This piqued her curiosity: Were such calluses a common issue?

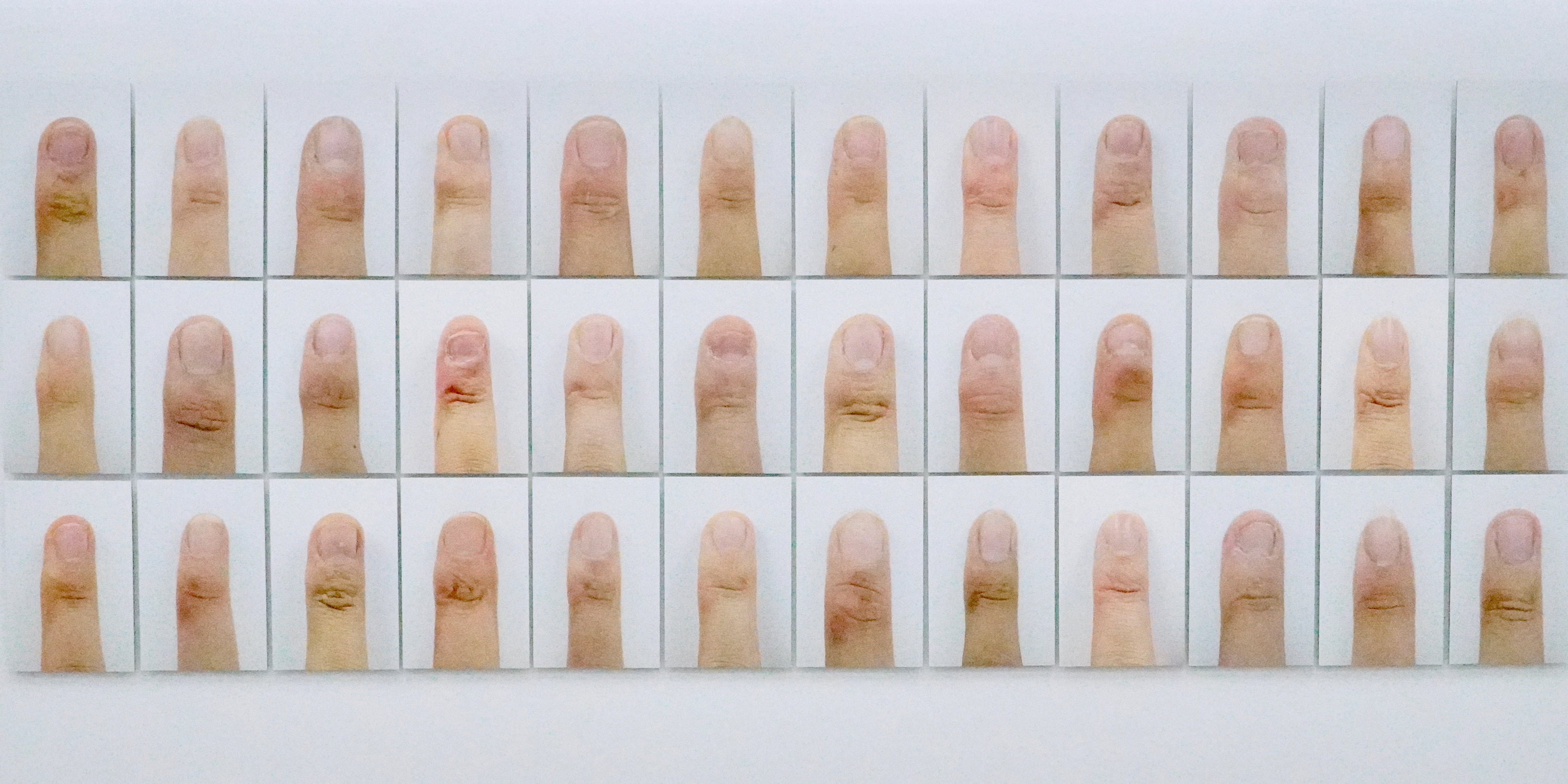

With her school’s blessing, Qiao converted an empty classroom into a small studio, setting up a lightbox and photography equipment. She photographed the fingers of 29 classmates, then printed the images in different sizes. Almost every finger had some kind of callus or deformity. One girl who could not stand the sight of her callus would pick and bite at it, causing it to crack. In the photos, the wound was magnified, showing flesh and wrinkled skin, which made Qiao feel both slightly scared and nauseous. To expand her sample size, she visited a nearby middle school and photographed 88 ninth-grade students. Contrary to her expectations, their calluses were just as big as those of their peers in high school.

Qiao compiled the photos into an exhibition, “The Body Being Shaped,” which opened on Aug. 17 at Zz Artspace in Xi’an. She wrote as an introduction: “My classmates and I are all striving to meet the expectations of others. ‘You should become this, you must do that.’ Somehow, completing homework has become the only way for us to reach our goals.”

Visitors to her show were amazed by the depth of reflection from an 18-year-old high school student. When images from the exhibition were shared on the Chinese social media site Xiaohongshu, they garnered 99,000 likes, and among the 18,000 comments were many photos of similarly deformed middle fingers. One viewer commented that her finger made her feel self-conscious, preventing her from holding hands or playing rock-paper-scissors with her right hand. Another said that their deformity faded at university but had reappeared in the past two years as they prepared for the kaoyan, China’s graduate school entrance exams.

Focusing on the issue

To better understand her classmates’ views on their calluses, Qiao created a seven-question “finger examination report card” modeled on a hospital checkup form. The results of the survey showed that 75% of the 117 students who responded spent more than six hours a day holding a pen, and 85% believed that finger deformation was normal. Among parents and teachers, 75% said they had not paid any attention to the issue. The vast majority of students were indifferent to their calluses, too, while one male high school student in an honors science class even said he liked his callus, as it serves as a symbol of his dedication to studying. “The bigger the callus, the better the student,” he said, adding that he felt no academic pressure at all.

Feng, who let Qiao photograph her finger, had heard similar things from relatives. In fifth grade, during a family gathering, she offered tea to a distant relative, who initially praised her hands for being fair and delicate, which signifies a life of fortune. Then, with a shift in tone, the relative compared Feng’s hand with their daughter’s, saying, “Her hands are severely deformed, unlike yours. You clearly have not worked as hard on your studies.” Feng says that she was still young at the time and instinctively took her elders’ comments to heart. She felt alarmed and even guilty, wondering if she truly was not working as hard as others.

In the eyes of Chinese parents, there are “good” and “bad” calluses. Feng loved playing the guitar, and she developed calluses on her fingertips as a result. Her parents would tell her, “If only you could apply that energy to your studies.” They had high expectations for Feng and rarely gave her verbal validation. She remembers when, in sixth grade, she proudly brought home a test with a score of 97, only for her father to focus on the three points she missed, saying, “Are you retarded?”

Feng’s educational upbringing was a painful one, with her parents constantly reminding her that other children studied until late at night or pushed themselves to the point of hospitalization. Although she did not fully understand the purpose of doing so, Feng followed their example. In her final year of school, she would wake up at 6:30 a.m., take just a 10-minute break at noon, and would continue doing her homework until at least 1 a.m. Eventually, she felt physically exhausted and began experiencing shortness of breath, headaches, and physical numbness. She was diagnosed with moderate anxiety and breast lumps, requiring monthly medication. Only then did her parents start paying attention to her health, hugging her, and offering comfort food when she seemed sad.

The attitudes of older generations toward finger deformities can influence children’s perceptions. Zou Wenqi, a journalism student at one of China’s prestigious Project 985 universities, first noticed her hands were developing calluses in primary school. Thinking she was sick, she showed it to her mother, who simply said, “It means you’ve been studying hard.” Zou was then learning calligraphy and her mother’s comment filled her with pride. However, over time, the callus became impossible to ignore, spreading to cover most of her middle finger. After completing a calligraphy sheet, her hand would shake uncontrollably. Zou bought rubber grips for the brushes but found them uncomfortable, so she gave them up.

Most of Zou’s classmates also had calluses, but they were largely indifferent. During routine school checkups, nearsightedness and hunched backs were identified as more common problems among students. Teachers had mixed attitudes toward these issues. While they would approve leave for sick students, they would also use such cases to encourage others to “learn from their dedication.” Zou once saw the slogan on the front of a school pamphlet: “Education is like growing a tree. You have to let the child grow freely.” She could not understand, then, why the school regulated even the length of a student’s hair and whether girls could have bangs.

In addition to deformed fingers, occasional headaches, and a tendency to eat too fast, Zou’s 12 years in education also left her with an achievements-based mindset. Last year, when she started at university, she noticed she still cared deeply about her grades in each class. In April, she and her classmates created a photography project commemorating their one-year anniversary since taking the gaokao. One of the photos shows a short-haired woman in a tracksuit wearing a medal around her neck while a pair of hands emerge from the shadows and grip her throat.

Life lessons

Now that she’s at a Project 985 university, Zou feels that her parents are truly happy. However, she has never told them about the pain and confusion she experienced during her high school studies. She worries maybe she’s too sensitive. “Other people don’t seem to have experienced the same suffering that I have, so surely it must be that my threshold for suffering is too low,” she says. Her mother was raised in a family that valued boys over girls, and as a result did not have the opportunity to receive a higher education. Zou believes that she is already lucky compared with her mother, so to complain would be to ignore one’s privileges. Even though she did not have a happy time at school, she still tells her 7-year-old sister to study hard.

After talking with classmates for her survey, Qiao surmised that the better a student performs academically, the more they tend to overlook certain problems within the education system. Among the visitors to her exhibition, those around her own age did not seem that moved. At most, they would remark, “Wow, everyone has a callus.” One of Qiao’s uncles, who achieved his county’s highest score in the 1994 gaokao, has a large, prominent, transparent callus on his right middle finger, but he had never paid attention to it before seeing his niece’s show. He asked whether the fingers in the images on display belonged to middle-aged people and was surprised to learn that they were the fingers of students aged 13 to 18. In the exhibition space, Qiao also set up a video installation that projected the faces of her classmates onto their respective fingernails, creating a striking contrast between their youthful looks and their worn, aged fingers.

During photoshoots, Qiao had a sense that when the fingers were enlarged and isolated, they almost turned into independent living entities. The bite marks on the nails, ink stains from test papers, and the hangnails along the edges all epitomized a person’s life experience. The hand became a snapshot, a form of identity, and a symbol for a life stage. For Qiao, the entire creative process served as a form of healing. She had rarely received recognition during her education, but through this project she found a group of people who she resonated with. “I’ve found acceptance,” she says.

From a young age, Qiao had followed the crowd and attended International Mathematical Olympiad classes and other extracurricular courses. She had little aptitude for numbers, words, or logic, and as early as first grade, she would work on homework until 11 p.m., spending much of her time practicing calligraphy. Her mother, who had a quick temper, often scolded her for being slow, and she had broken four clocks in frustration. Her desk still bears the scars of where one clock was smashed to bits.

In high school, Qiao felt so guilty about her lack of self-discipline that she used a pen to cut her arm, leaving marks that lasted for months. Her mother now reflects on those times and concedes that it was wrong to compare Qiao with other children. She even used to cook meals for her daughter’s math tutor to ensure she would receive more attention. She looks back at this behavior with amusement. Qiao’s father has mostly been uninvolved in her education, but in preparation for the exhibition, he helped with adjusting the camera aperture and other settings, and looked over the printing quality. Not long ago, he told Qiao that he felt like she had suddenly grown up. She notices that when her father now talks with friends, he will say, “Our child is making changes to our system of knowing the world.”

Qiao invited Feng to see the exhibition, but Feng did not have time before heading off to university. She was accepted into a Sino-foreign joint venture university and plans to study abroad in two years. Encouraged by her parents, Feng had enrolled in IELTS classes to improve her English. Before the university entrance exam, she did not dare tell her parents that she had participated in Qiao’s photo project, fearing that they would criticize her for not putting the energy into her studies.

After entering university, Feng began using hand cream every day and even trimmed part of the callus on her middle finger. Several weeks later, there was still a brownish residue and a slight indentation in the top knuckle. Finding herself in a less-strict environment at college, she noticed that almost all of her classmates seemed to be indulging in a sort of “revenge freedom” – staying up late, eating excessively, partying, and dating. She says she suddenly had the urge to get her nails manicured for the first time — a minor act of defiance and self-care. At that moment, she thought, even if the manicure lasts only a short time, at least I did it.

(Feng Xiao and Zou Wenqi are pseudonyms.)

Reported by Lü Xucheng.

A version of this article originally appeared in White Night Workshop. It has been translated and edited for brevity and clarity, and is republished here with permission.

Translator: Vincent Chow; editors: Wang Juyi and Hao Qibao.

(Header image: Photos on display at the “The Body Being Shaped” exhibition in Xi’an, Shaanxi province, August 2024. Courtesy of Zz Artspace)