Echoes of War: The Untold Story of the Lisbon Maru

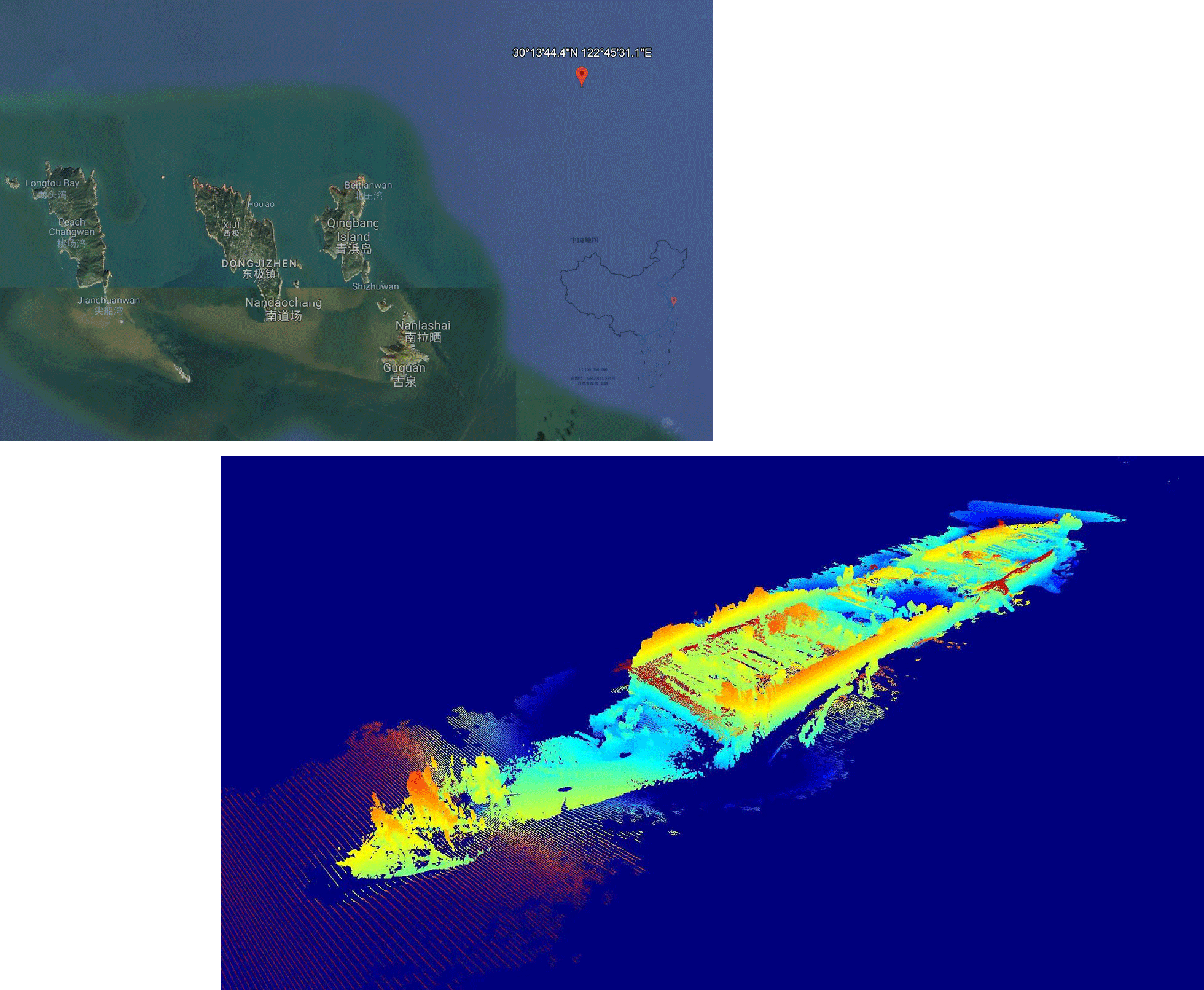

In late September 1942, 1,816 Allied prisoners of war were imprisoned on a Japanese military cargo liner, the Lisbon Maru, to be transported from Hong Kong to Japan. After three days of smooth sailing, the vessel was torpedoed by the USS Grouper off Dongji Island, part of the Zhoushan archipelago in China’s eastern Zhejiang province.

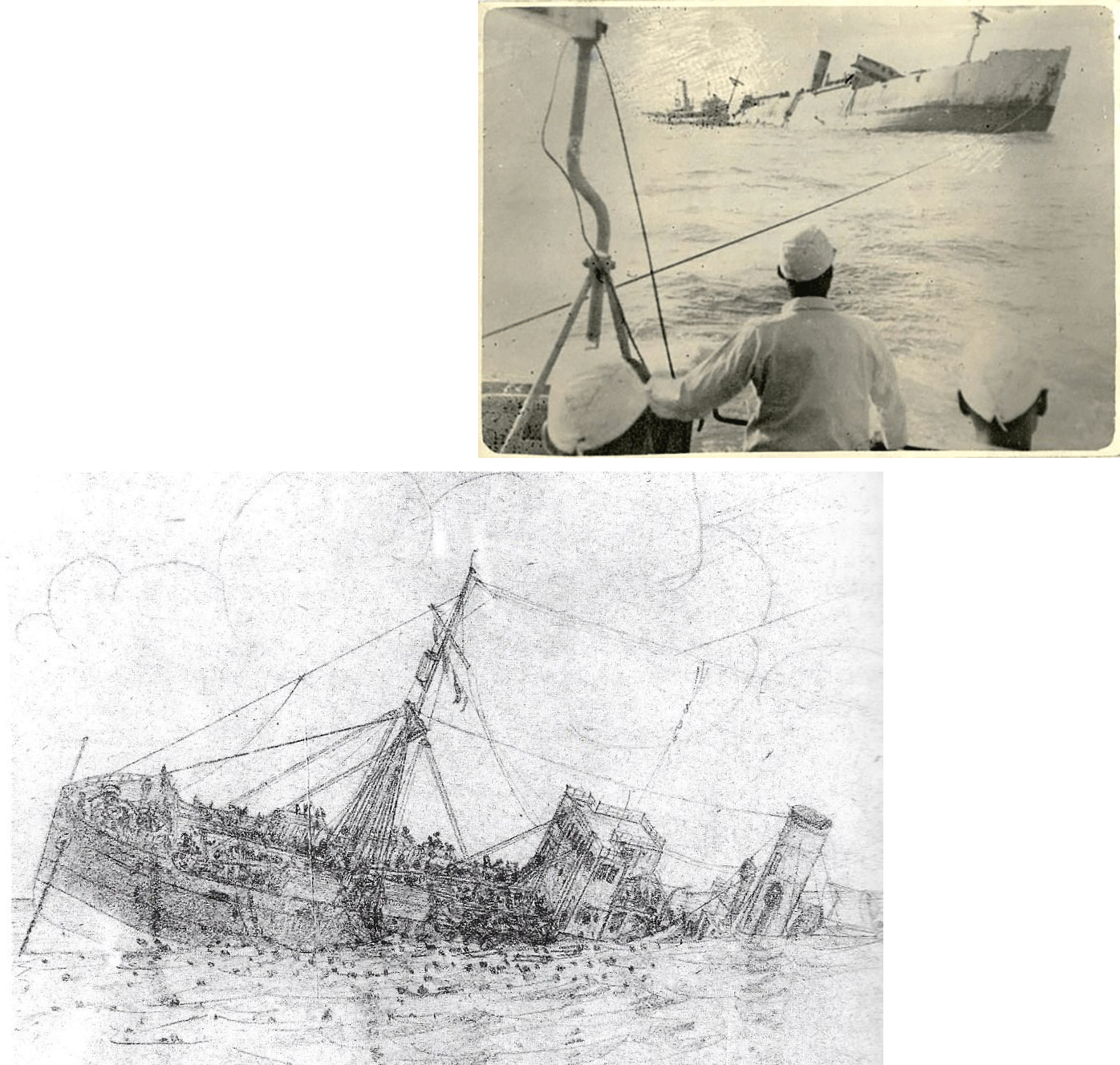

After the torpedo strike, the Japanese troops onboard locked the POWs — mostly British soldiers and airmen — inside the cargo hold, nailing wood planks and canvas sheets across the entrance. Over the next 25 hours, as the Lisbon Maru was sinking, the POWs did everything they could to save themselves. After finally breaking free from the hold, they jumped into the sea, where they came under fire from their Japanese captors. Zhoushan fishermen sailed to the rescue in their sampans, saving 384 men from the brink of death and providing them with food, clothing, and shelter. However, 828 POWs perished that day, either by being shot, drowning, or dying in the dank, cramped cargo holds. The Japanese military only began lifting the men from the water once the Chinese fishermen became witnesses to the atrocity. The Lisbon Maru ultimately sank beneath the waves off the Zhoushan Islands.

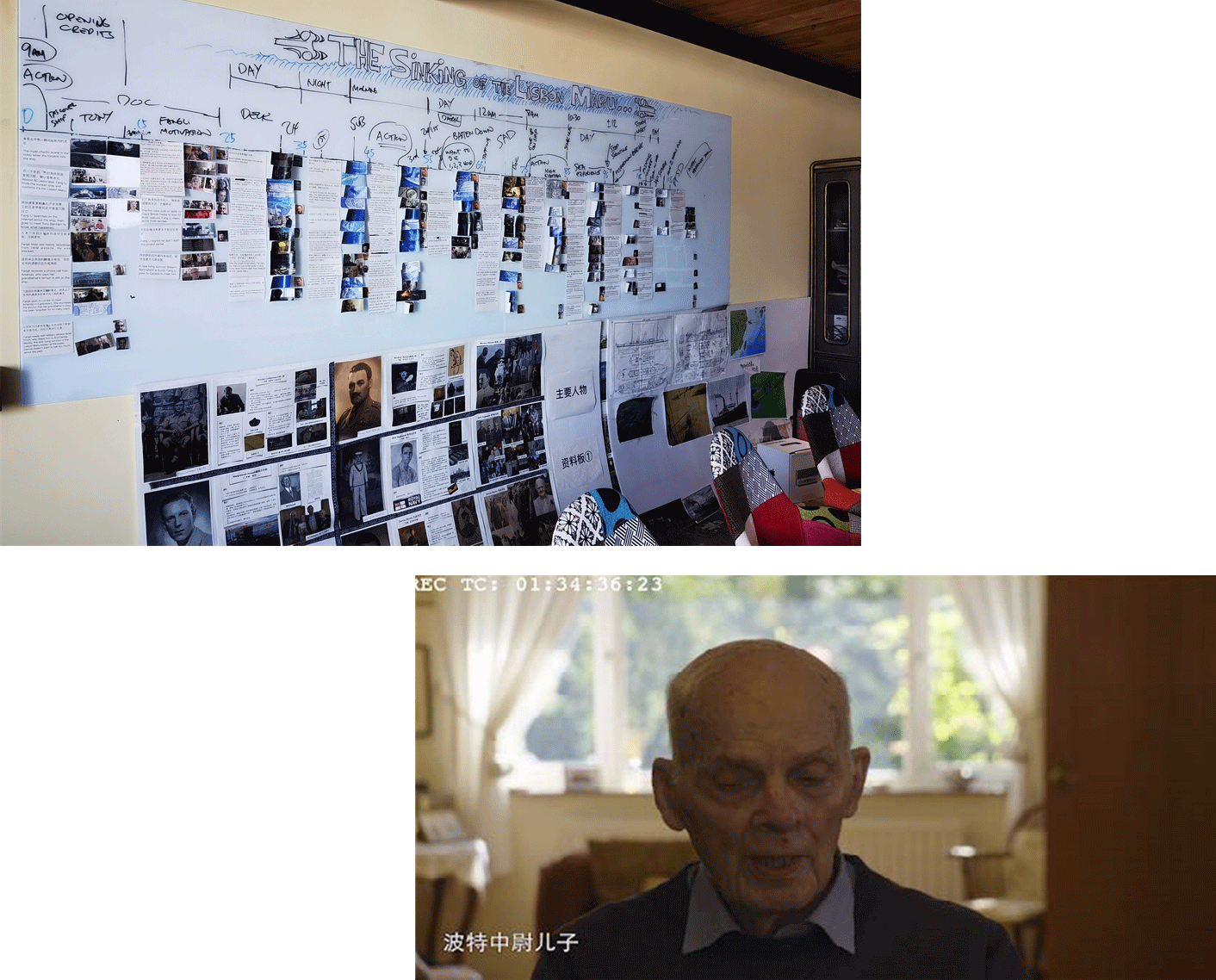

In 2014, while making a movie on Dongji Island, film producer Fang Li overheard a fisherman mention that there was a sunken ship from World War II nearby. Fang, who studied geophysics at the East China University of Technology, had previously worked in the integration of earth probes and ocean survey equipment. With his curiosity piqued, Fang led a team of oceanographers to survey the area in 2016. “I wanted to find the sunken ship. After finding it, I then wanted to find the people connected to it, to learn their stories. What did they experience that day 82 years ago? We unearthed the whole story. Now it’s time for other people to hear it.”

In the following interview, Fang recounts how he came to unearth this forgotten tragedy and retell it in his documentary “The Sinking of the Lisbon Maru.”

The Paper: From a technological standpoint, could you talk about why in the 75 years from 1942, when the Lisbon Maru sank, to 2017, when you led a team to locate it, that no one had found the wreckage? We now know that it sank in waters off Dongji Island and sits just 30 meters below the surface.

Fang: That no one found it in the past didn’t have anything to do with the ocean’s depth, but rather with the ocean coordinates. GPS and China’s own compass navigation system didn’t emerge until recent decades, and during WWII, ships still relied on sextants, which were imprecise. Moreover, in the past, people relied on coordinates of the Lisbon Maru obtained from Japanese military logs the year it sank. The true coordinates of the sunken ship are 30°13'44.42"N 122°45'31.14"E — 36 kilometers from the coordinates in the Japanese military logs.

The Paper: Why did you decide not to recover any artifacts that might remain in the wreckage of the Lisbon Maru?

Fang: That’s pretty complex. The Lisbon Maru is a Japanese vessel, and after WWII ended, the United States took over control of Japanese military artifacts, and the ship sank in Chinese waters. The victims were all British soldiers and airmen, and the diplomatic jurisdiction was unclear. In addition, from an engineering and technological perspective, the ship — sunken so long ago and near the continental shelf — had already become severely decayed and corroded by rust. Add to this the 70 or so years of nets cast by fishermen, resulting in many fishing nets covering the wreckage. In 2019, when the underwater archaeology team of the National Administration of Cultural Heritage came to survey the area, we also supplied them with equipment. For one month we tried to use winches to lift the fishing nets from the ship, and even with 1 ton of force applied, we were unable to lift them. Sending divers underwater to rescue artifacts from the ship was also unrealistic: on one hand, the underwater currents are unpredictable; on the other, the divers might get tangled in the fishing nets and get stuck down there.

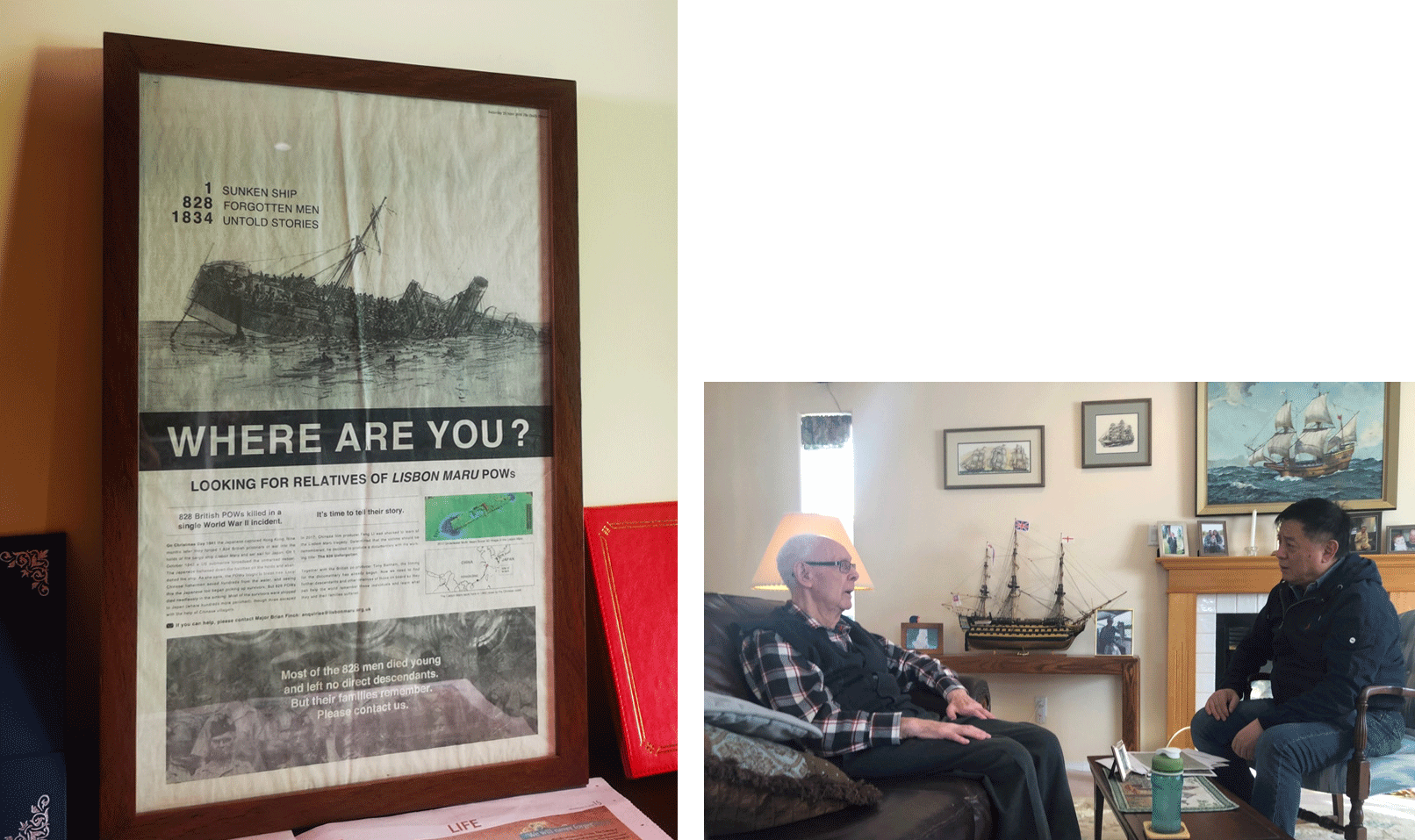

Could we recover the remains of the victims? I actually researched this question. In the United Kingdom, I specifically asked Brian Finch, who once worked in the UK Diplomatic Service and has devoted great attention to researching the Lisbon Maru incident. I consulted with him on military affairs for the documentary. Brian told me that ships sunken in wartime can actually be considered war graves — one should not disturb the souls. We argued about it. I believe that the victims of the Lisbon Maru did not truly die while fighting in the war, as they were killed as POWs. Therefore, the Lisbon Maru beneath the ocean cannot be considered a grave, but rather a prison. There were 200 or so British soldiers underwater there, and they had no way to escape before the ship sank, as the Japanese had nailed them inside the bulkhead compartments. Then, in 2018, I did three interviews with descendants of the British POWs onboard, and they were split roughly 50-50, with half of them hoping for their ancestors’ remains to be returned home, and half feeling that owing to the traditional designation of war grave, the dead onboard should not be disturbed.

The Paper: From finding the wreckage to bringing those POWs’ stories to the silver screen, who was the first person or what was the first story that moved you?

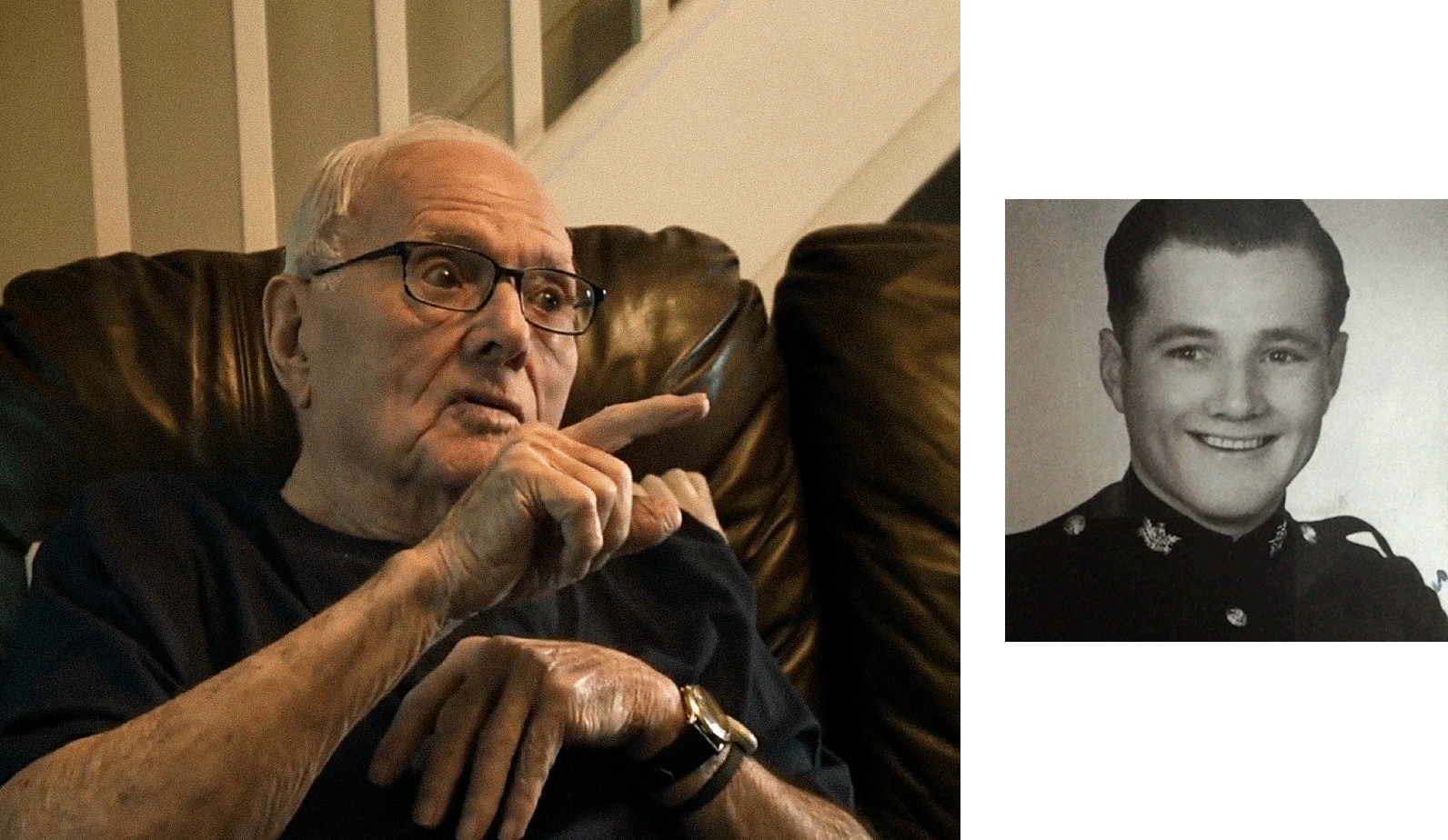

Fang: I initially wanted to make a TV documentary, something that would primarily be composed of interviews and could function as a short or special report. So in April 2018, the first time I went to the UK to do interviews for the documentary, I met 99-year-old Dennis Morley. His birthday was Oct. 26, the same day as my daughter’s. I promised Dennis on the spot that when he turned 100, I would give the documentary to him as a birthday present. That was when I had just started, and I was thinking simplistically. Besides him, the remaining descendants of the ship’s POWs only numbered in the teens. I planned to make a series of short videos, so a little more than half a year would surely be enough time.

Before even the end of the first interview, I just couldn’t handle it. The stories of family, love, and friendship between the POWs totally got to me. I couldn’t bear it. I would close my eyes and immediately start thinking about an empty family tomb, nothing remaining of a young man of 22; a little daughter holding a doll waiting 70 years for her father to come home… 1,816 POW families, 255 fishermen families, this incident impacted so many people, and in my hands, I held a list of the names of only a few people. I felt spurred into action and decided to continue to dig deeper, to find more of those people related to the incident, to increase the persuasive power of the story.

The Paper: Is that when you decided to place ads in The Sunday Times, The Sunday Telegraph, and The Observer newspapers to look for more relatives of the POWs?

Fang: The last two or three days of my first trip to the UK, I went running around to several newspapers to bargain and negotiate. They were all very friendly, and thought that this was not only business but also an act of service. The advertising manager at the Telegraph heard about the interviews I had already done, and she couldn’t help but cry, especially upon hearing that several Chinese people had come to the UK to find their descendants. She said that the paper would definitely give me the best price. We put out full-page ads in those three popular British newspapers to look for people every Sunday for two months. The BBC also invited me for an interview to talk about the project, which received a big response. After my interview at the British Royal Marines Club, an elderly man waved a 10-pound note at me. That was the first donation we received in 2018.

Some 380 descendants with family ties to the incident then contacted us in succession, and in the process, we came upon another living survivor, William Beningfield, who was living in British Columbia, Canada, and had been rescued by Chinese fishermen. The best way to return to historical events is through material evidence and personal testimony. For material evidence, we had found the sunken Lisbon Maru, and for personal testimony, we had the living survivors. No matter if it was the British POWs or the Chinese fishermen, I understood that the incident was a sort of “tail end” of history — if no one continued to relate the event, then it would vanish into oblivion. Throughout 2018 and 2019, my main work was doing interviews to salvage the stories within people and record them.

The Paper: Could you tell us about how you brought the story of the Lisbon Maru to cinema screens?

Fang: The aim of making this movie — my whole motive, hope, and driving force — was not simply to present history to others, but rather to tell a story about “people.” It’s a humanistic movie. The film runs 122 minutes, and 80% of it is the story of the POWs’ fate, the rupturing of families, the gap between two generations, and the great joys and sorrows of life. All of us involved in the making of the movie understood that seeing it on the silver screen is an immersive experience. Viewers would be enveloped by the story, helped by lighting and sound, and the emotions the story inspires are extremely intense. Putting it on screens was my decision, and my financial responsibility. I firmly believed that such a humanistic story deserved to be shown in cinemas and shared with the public. And what are movies? Movies are acts of sharing, and that’s their charm. “The Sinking of the Lisbon Maru” is a documentary, and it shares its name with the book written by Dr. Tony Banham, which is deliberate. It seems like the two of us are running a relay race of words and images. His book set the foundation for my work, and he shared all the information he had with me. Our shared hope has been to unearth this piece of history.

The Paper: In the interviews with the survivors and their descendants, you were able to share some materials you had obtained with them. Did this leave you with any deep impressions?

Fang: Lt. Alan Stanley Potter, who was on board the ship, could speak Japanese. After the Lisbon Maru was torpedoed, the first thing he did was to run up to speak with the Japanese officers, imploring them to free his comrades from the hull of the ship. As a result, Potter was shot to death. It’s an incredibly valiant story, and we only learned of the nature of his death by going over many, many recollections. At the time of the tragedy, Potter’s son had received only a death notice from the military and was unaware of how his father had died. Our interview was the first time he had learned the whole story. The value in this movie can also be found here: helping so many children, who have been yearning all these years, to finally understand what really happened to their fathers.

The Paper: Your movie contains stories told by Chinese, English, American, and Japanese interviewees. Owing to historical and contemporary reasons, what kind of preparation did you do before interviewing Japanese scholars and the descendants of the captain of the Lisbon Maru?

Fang: In order to find the son and daughter of Kyoda Shigeru (captain of the Lisbon Maru), we specifically went to the department of household registration at the Shinagawa Police Station in Tokyo. For privacy reasons, the police could not tell us their current address. Later, we found a private detective agency in Shinjuku, Tokyo. Even though we felt that was a bit unorthodox, they were able to trace the descendants of the ship’s captain. Shigeru’s son and daughter had no idea about the incident, and were both quite surprised to read the transcripts that we showed them from their father’s trial.

The Paper: When Kurosawa Fumiki, a Japanese professor, recounts the incident in the documentary, he says, “In choosing between guarding the POWs and preventing them from escaping, the Japanese soldiers chose the latter.” This sounds like a rationalization.

Fang: That quote is Professor Fumiki’s personal opinion. He is the president of the Military History Society of Japan. As a researcher, he analyzes the psychological motives of the Japanese military at the time. Lt. Wada Hideo of the Japanese Imperial Army led 780 soldiers in guarding this group of POWs, and after they had been hit by the American’s torpedo, they sealed the ship’s ballast area, shutting in POWs who would later be found floating on the surface of the water. In Professor Fumiki’s opinion, this was all to prevent the POWs escaping. So, I asked him, were the lives of these British men not truly considered lives? Was the Japanese military’s handling of the situation not murder? There were more than 10 Japanese military ships nearby that certainly could have come forward to save people at a moment’s notice. I had backed Professor Fumiki into a corner. He eventually said that the Japanese side must be responsible for the enormous amount of Allied deaths, and assume responsibility for the humanitarian disaster. This is a documentary. I hope to objectively bring to light the perspective of all parties involved and let the viewers decide for themselves.

The Paper: A British singer in the documentary performs a song with the line: “I told you it was true, the Lisbon Maru.” Can you tell us about the movie’s soundtrack?

Fang: When we were doing interviews in the UK, we heard that there was a singer by the name of Tom Hickox who had composed a song for the Lisbon Maru. He later gave us permission to use the song for free in the movie. Another song is called “Long Way From Home,” and it’s the last song in the film. It was composed by Howie B, a songwriter for the band U2. Li Yu (the movie’s art director) also helped me connect with French composer Nicolas Errera, who flew out to Beijing during the pandemic specifically to score for us. He stayed 10 days, and he and Li decided on the final version of the soundtrack. I generally planned the narrative for “Long Way From Home,” and the Dutch artist on our team, Jerry Verschoor, wrote the lyrics — he’s also a poet. I told Jerry that this song has to express a mother calling for her son, a wife calling for her husband, a son and daughter calling for their father… and has to express a type of glory, as we hear the song at the end of the chapter “A Farewell to Dad.” We hope that these souls are able to rest, and never again be lonely in the darkness of the ocean. Jerry wrote eight drafts, finally arriving at a place where he had all the elements I wanted.

The Paper: You seem to have feelings and motivations for making this film that go beyond the role of a professional filmmaker.

Fang: When we were searching for the Lisbon Maru, I was standing on the deck, 800 or so vivacious lives extinguished beneath my feet. It struck a chord in me. I really have a hard time expressing my feelings about that moment. Aug. 7, 2019, was the last time I went to London to conduct interviews, and I was getting together with the descendants of the three British comrades on the Lisbon Maru. I was going to introduce everybody to each other — their fathers had all perished with the ship after being sealed in, and had no hope for escape. While talking, I suddenly had a thought: Why don’t they come back to China with me and go to the spot on the ocean 30 meters above their fathers and say goodbye? The three older people all started sobbing when I proposed this. In the end, on Oct. 20, 2019, 14 descendants of the victims came to visit the final resting place of the Lisbon Maru. We performed a funerary rite. In the prayer, there was a phrase: “They shall not grow old, as we that are left grow old. Age shall not weary them, nor the years condemn. At the going down of the sun, and in the morning, we will remember them.”

Reported by Wang Zheng.

A version of this article originally appeared in The Paper. It has been translated and edited for brevity and clarity, and is republished here with permission.

Translator: Marianne Gunnarsson; editors: Wang Juyi and Hao Qibao.

(Header image: A promotional image for the documentary “The Sinking of the Lisbon Maru.” From Douban)