The Puzzling History of China’s Most Controversial Flavoring

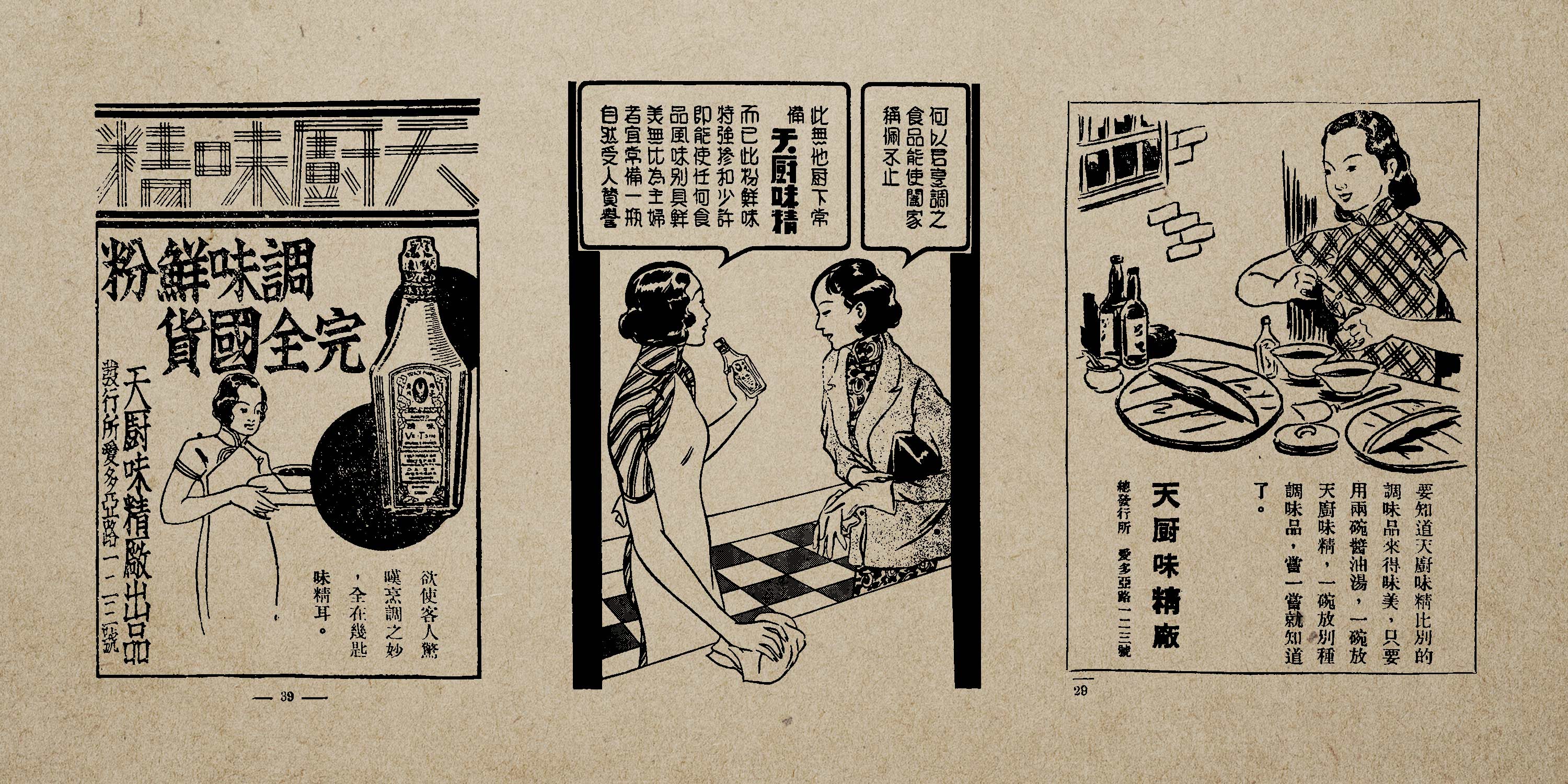

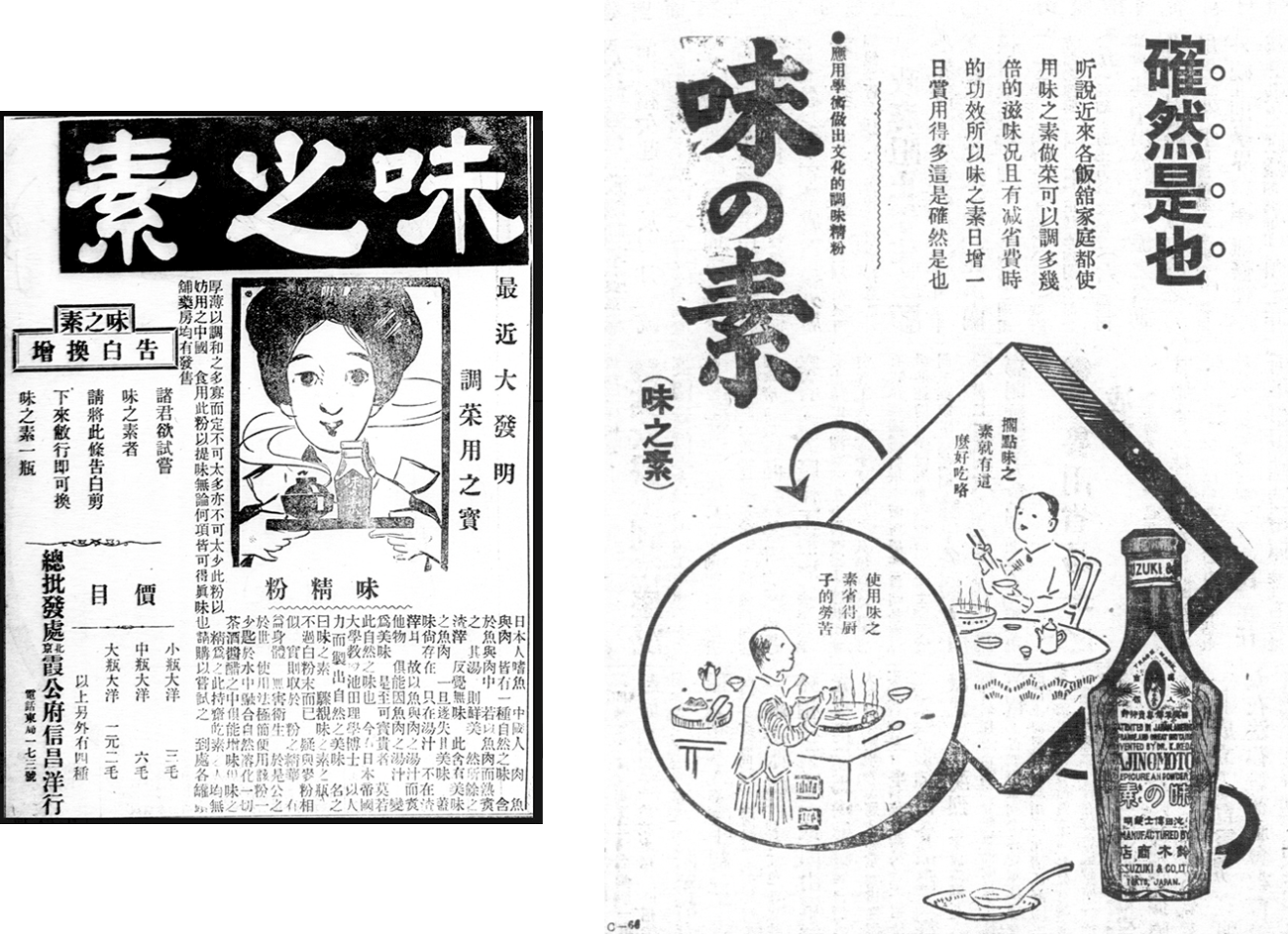

In the early 1920s, the Chinese chemist and entrepreneur Wu Yunchu sensed an opportunity. Less than 10 years prior, the Japanese firm Ajinomoto had introduced a new food additive, monosodium glutamate, better known as MSG, to the Chinese market. First distilled from kelp by the scientist Kikunae Ikeda in 1907, MSG was quickly embraced by Chinese diners, but Japan’s increasingly aggressive posture toward China had made Ajinomoto a target of boycotts.

Seeing a chance to displace the market leader, Wu figured out a way to isolate MSG from wheat in 1922. The following year, in collaboration with Zhang Yiyun, a sauce and pickle magnate, Wu founded the Tienchu Ve Tsin Factory to produce and market his invention. (In the modern pinyin romanization system, ve tsin would be spelled weijing, the Chinese for MSG.)

Over a century later, it’s almost impossible to imagine Chinese food without MSG. But the seasoning’s success was by no means baked in. From the initial boycott to more recent panics about its health effects, MSG’s place in the Chinese public consciousness has fluctuated wildly over the past century.

Arguably, the most important early proponents of MSG’s spread in China weren’t restaurants or home cooks, but Buddhists. According to the scholar John Kieschnick, the rise of MSG in China in the 1920s was closely linked to vegetarian and Buddhist communities. Yinguang, one of the most respected Buddhist masters of the era, even paid a special visit to Wu’s factory. That trip would prove decisive, as it dispelled Yinguang’s doubts that MSG was made from animals and convinced him that the flavoring could help convert Chinese people to vegetarianism. After all, why eat meat when vegetarian dishes with MSG tasted so delicious?

Yinguang would go on to write multiple articles extolling the benefits of MSG and praising Wu’s work as a “virtuous achievement.” Strictly speaking, this wasn’t new: As early as 1914, Ajinomoto’s advertising copy highlighted MSG’s benefits for vegetarians, emphasizing that it lacked the “smell of blood and flesh” and could be “enjoyed freely” by those who didn’t eat meat. But Wu leaned even further into the association, selling his product under the “Buddha’s Hand” trademark.

Meanwhile, as tensions between China and Japan culminated in a major nationwide boycott of Japanese products, the company rolled out a slogan calling on patriotic Chinese to buy domestic goods. Wu became a national hero. Within a decade, his factory went from producing 3,000 kilograms of MSG a year to almost 160,000 kilograms annually.

That growth was not entirely due to vegetarians, of course. A review of mid-20th century cookbooks shows that MSG had become a national phenomenon, from Beijing to the southern province of Guangdong. More than 70% of the reviewed recipes — vegetarian or otherwise — called for the flavor enhancer.

The widespread use of MSG continued through the 1990s. Around the early 2000s, however, rumors began circulating in China that MSG was linked with cancer, and a number of restaurants explicitly disavowed its use. Diners flocked to a supposedly healthier alternative, “chicken essence,” or jijing, which was seen as less industrialized than MSG.

There was just one problem: MSG makes up roughly 60% of the ingredients in a packet of chicken essence. While MSG’s reputation has taken a hit in recent years, sales continue to be strong, in large part due to MSG’s continued use in jijing and soy sauce. A 2024 market report by research firm Mintel found that MSG consumption remains on the rise in the Asia-Pacific region, though manufacturers are conspicuously tight-lipped about its use.

Even that strategy has its risks. In 2022, the food brand Haitian found itself under fire after social media users noticed it used different ingredients in its domestic and foreign-market products. The version sold in China contained additives such as monosodium glutamate, flavor-enhancing nucleotides, and artificial sweetener sucralose, while the overseas version listed only water, soybeans, salt, sugar, and wheat. The resulting controversy wiped $8 billion off the company’s valuation.

In her book “Purity and Danger,” anthropologist Mary Douglas describes how ideas of purity and impurity are shaped by culture, and what one culture considers clean may be considered unclean in another. The boundary between purity and impurity is never absolute. MSG was once the star ingredient of much of Chinese cooking — a scientific breakthrough and the key to healthy vegetarian living. Now it’s considered more industrialized and less “pure” than meat-based additives like jijing. Nevertheless, it’s unlikely to lose its spot in the Chinese pantry anytime soon.

Translator: David Ball; editor: Cai Yiwen.

(Header image: Ads for an MSG brand from the Republic of China period. From @同观阁书斋 on Kongfz.com, reedited by Sixth Tone)