Cigarette Sales Are Rising in China, Defying Global Trend

For 21-year-old college student Ying Yuhao, smoking is an essential tool for building relationships.

During his summer internship at a government agency in the eastern city of Hangzhou, Ying recalled senior colleagues offering him cigarettes during meals. “If I didn’t accept, it would seem like I was disrespecting them,” he said. “I smoked almost every day.”

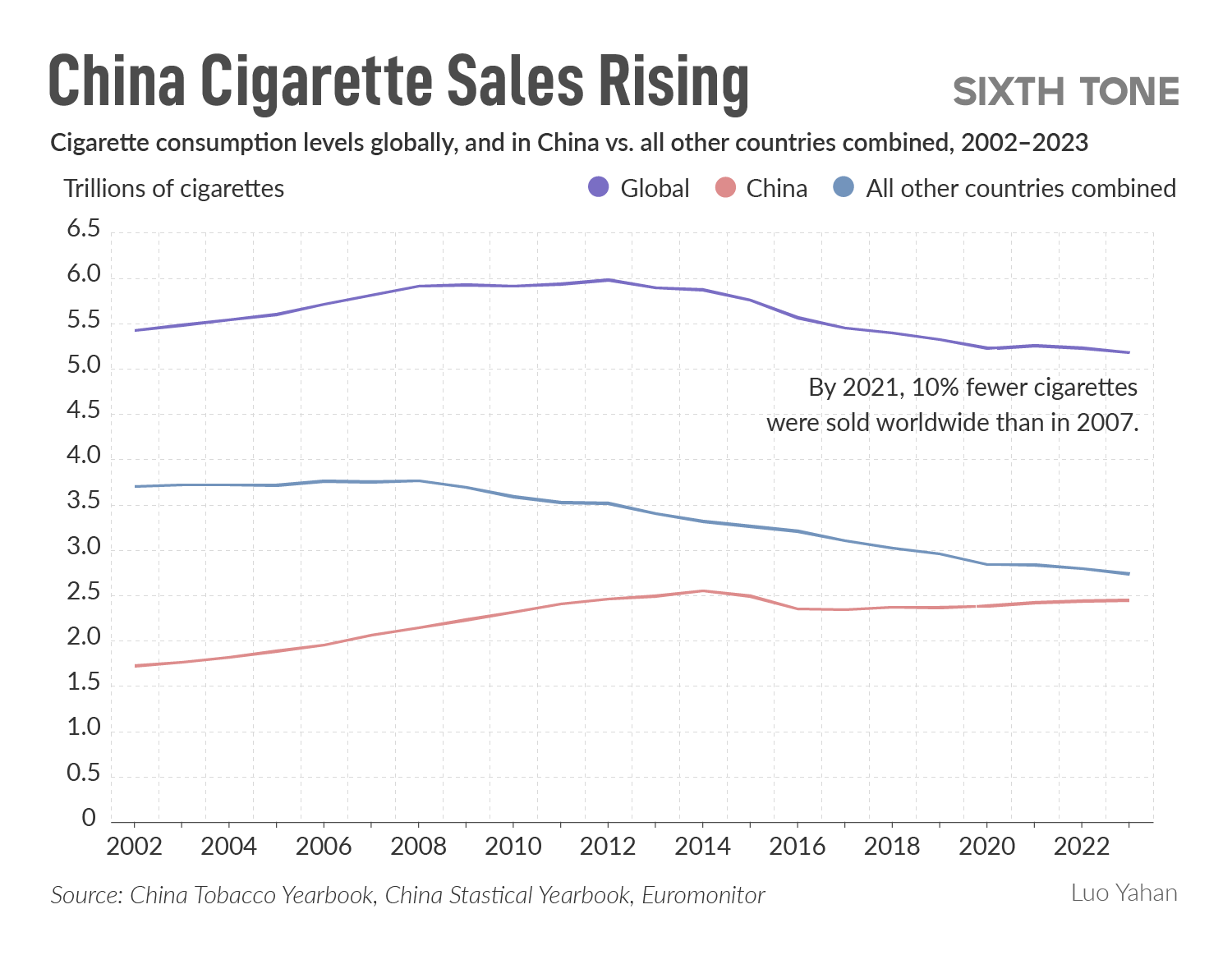

China is the largest producer and consumer of tobacco in the world, and cigarette sales have grown in recent years, bucking the global trend of falling consumption. Policies in some regions to restrict smoking, such as indoor bans or steeper taxes, have stalled in recent years amid official concerns about their negative economic impact, according to experts.

After a decline from 2014 to 2016 as several major Chinese cities introduced tough indoor smoking bans, cigarette sales have again risen over the last five years, reaching 2.44 trillion in 2023, according to an August report by the state-backed ThinkTank Research Center for Health Development.

One driver of increasing Chinese cigarette consumption is the popularity of “slim cigarettes” among younger smokers due to their fashionable designs and a mistaken perception that they are less harmful than regular cigarettes, according to Jiang Yuan, deputy director at the ThinkTank Research Center.

Marketing plays a significant role in their appeal, giving them a more sophisticated and stylish image.

“Some tobacco companies specifically produce shorter cigarettes, for example, for high-speed train passengers who can’t take more than a few puffs before discarding them,” Jiang told Sixth Tone, referring to smokers who take advantage of the brief platform stops taken by Chinese trains.

However, health experts emphasize they are no safer than other tobacco products — with each slim cigarette equivalent to a third or a half of a traditionally-sized cigarette.

The rise of smaller cigarettes could explain why total sales rose as the national smoking rate fell slightly. China’s adult smoking rate decreased from 26.6% in 2018 to 24.1% in 2022, according to official statistics.

That’s well above the global rate of 17% in 2021. China has an official aim of reducing adult smoking prevalence to 20% by 2030. Meeting that will be a challenge without a policy shift, Jiang said.

What makes China’s numbers stand out even more is that the rest of the world is buying fewer cigarettes. As a result, China represented close to half of all cigarettes sold worldwide in 2023, up from about a third of sales two decades ago.

“China has recorded an increase both in sales volume and market share when global cigarette sales declined significantly,” Jiang said.

Jiang attributes the divergence between Chinese and global cigarette consumption partially to the growth of the e-cigarette industry outside of China. That growth has been limited in China by tough regulations — including a ban on all non-tobacco-flavored vapes in 2022.

Anti-smoking policies in China will have to aim mainly at men: more than half of male adults in China smoked as of 2018, according to official data, compared to about 2% of women.

Ying, the student, said smoking is common even at his college, where many of his peers consider it a skill they need to integrate into the workplace in the future.

“Honestly, I don’t like the smell of smoke and know it’s bad for my health,” he said. “But sometimes when I’m stressed or working late into the night, a cigarette helps me relax and stay awake.”

Stagnant legislation

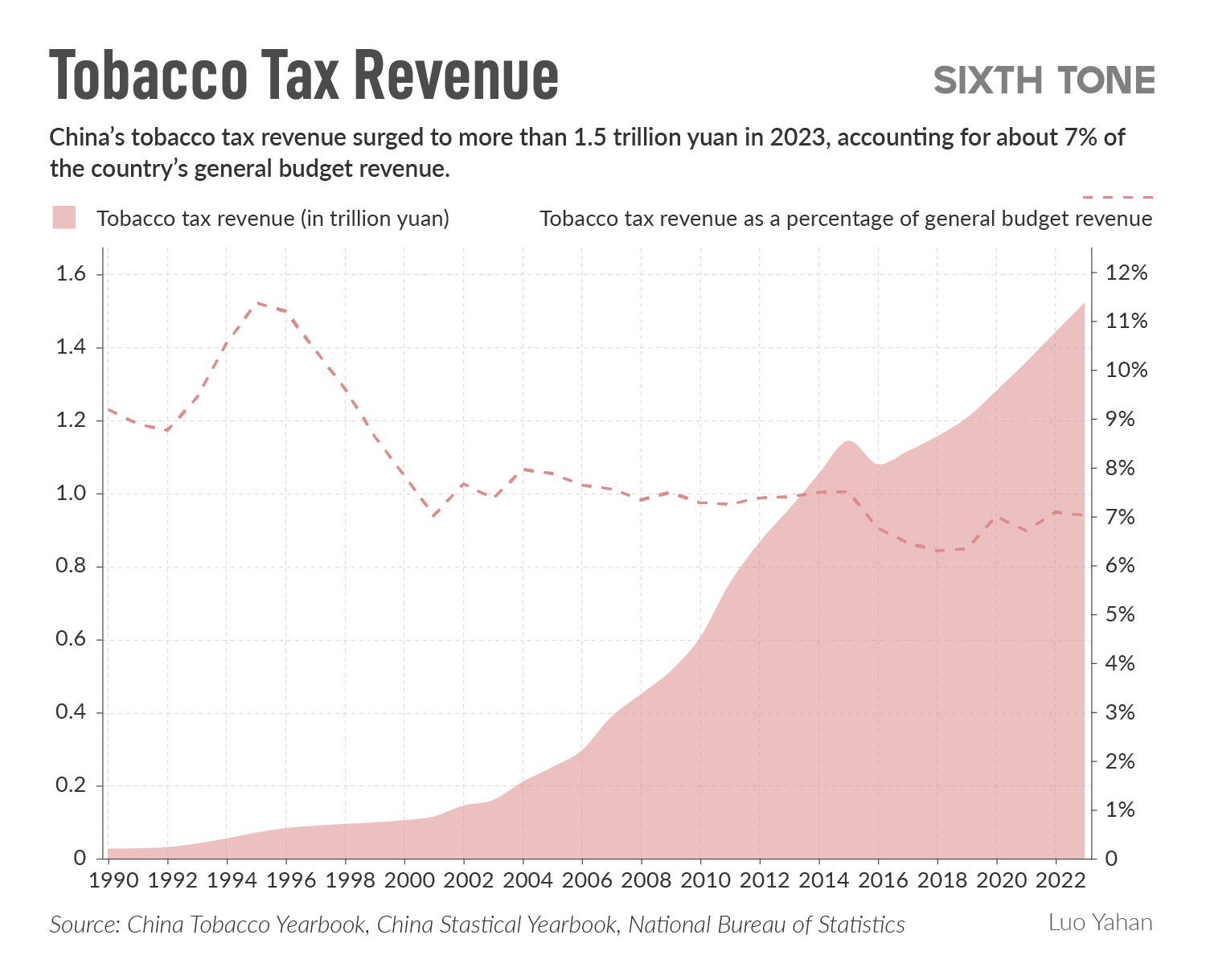

The importance of cigarette taxes for government income and the influence of tobacco and hospitality businesses have slowed the pace of anti-smoking measures in China, according to experts, despite a mounting health cost to the nation.

About a decade ago, smoke prevention laws were gathering momentum in China, with Beijing introducing a ban on smoking in all indoor public places in 2015, and Shanghai following a year later.

The Shanghai rules have been well-enforced: smoking has only been reported in about 12% of banned zones, according to an official post, while the city’s adult smoking rate dropped below 20% last year.

Local governments are becoming more cautious: when the southwestern city of Chongqing introduced smoking restrictions in 2020, they were weaker than earlier rules, allowing designated smoking areas in hotels and bars. Several other cities including neighboring Chengdu and Dalian in the northeast followed suit.

“Legislation on tobacco control has stagnated or even backslided in some regions,” Wang Qingbin, a professor in the School of Law-Based Government at the China University of Political Science and Law, told Sixth Tone.

China’s recent economic slowdown has made officials more cautious about disrupting the cigarette industry, according to Wang, with tobacco companies being major generators of employment and government revenues.

Cigarette taxation has become a more important source of government income in recent years. From about 6% of the government’s general public budget revenue in 2018 — a record low due to stricter tobacco control policies — tobacco taxes rose to more than 1.5 trillion yuan ($210 billion) in 2023 — approximately 7% of the general public budget’s income.

Regulators pushing for restrictions face pushback from multiple fronts, including state-owned cigarette companies, which are significant economic contributors in some regions, as well as local governments wary of losing tax revenue and business owners who argue that smoking bans could lead to decreased foot traffic, especially for restaurants and cafés.

China has not adjusted tobacco taxes in recent years, while household incomes have continued to rise, making cigarettes more affordable. Taxation on China’s most-sold brands is 52%, much lower than more than 80% seen in countries such as the UK and New Zealand.

China lacks a nationwide anti-smoking law after a draft introduced in 2014 to comply with a World Health Organization agreement didn’t pass. As a result, China’s anti-smoking legislation primarily depends on regional laws.

Wang noted a trend among local governments to issue smoking rules as “guidance” to residents rather than as regulations that can carry fixed penalties. That undermines their effectiveness in actual enforcement, he added.

“It is urgent to accelerate nationwide tobacco control legislation,” said Wang.

Illness and healthcare costs associated with smoking arguably far outweigh any economic gains. By causing diseases such as lung cancer, tobacco smoking is estimated to account for more than 1 million annual deaths in China, according to a 2020 government report.

It’s not all been backsliding: a notable step forward in tobacco control came in 2020 when China incorporated a smoking ban for minors into law, which includes prohibiting cigarette sales near schools.

But in a demonstration of cigarette company’s marketing power, collecting cards created from folded cigarette packs for use in schoolyard games has become a craze among Chinese schoolchildren in recent years, leading to public concerns that the proximity to tobacco-derived products will make them more likely to smoke in the future.

Polls have shown widespread support in China for indoor smoking bans, and more Chinese people are traveling abroad and picking up ideas about tobacco control. Lin Zejun, who lives in southern China, said he was impressed by the gruesome images on cigarette packages overseas. “It’s full of explicit warning images. This is something we could adopt,” he said.

Nonsmokers in China — predominantly children and women — also face serious risks. Nearly 70% of nonsmokers are exposed to secondhand smoke in public areas, with places like bars and restaurants seeing the highest prevalence, according to the 2020 government report. More than 50% of people have some exposure at work, it added.

One such nonsmoker is Song Bijun, who developed lung nodules and thyroid disease two years after graduation. She used to work in an office next to her Shanghai building’s property management team, where employees frequently smoked indoors, leaving the walls blackened.

“I believe secondhand smoke is one of the factors contributing to my health issues,” the 29-year-old told Sixth Tone.

Song now works in an office with a smoking ban, but the nearby bathroom has turned into a haven for smokers. She wears a 3M-brand mask securely over her nose and mouth when using the facilities.

The office building’s management and local health commission told Song there is little they would need to catch people in the act of smoking to issue a fine, and they don’t have enough staff to carry out monitoring.

Disappointed by the response, Song has taken matters into her own hands. She started wearing a T-shirt that says in bold letters: “Smoking is harmful to your health.”

Editor: Tom Hancock.

(Header image: IC)