Mind’s Eye Blind: A Shanghai Clinic Treats a Disorder None Can See

Throughout his early life, Meng Xingchen had no idea his brain works differently to most other people. He’s unable to visualize even simple concepts in mathematics and science, nor can he conjure thoughts of places and people he’s seen just moments earlier. In his mind is only darkness.

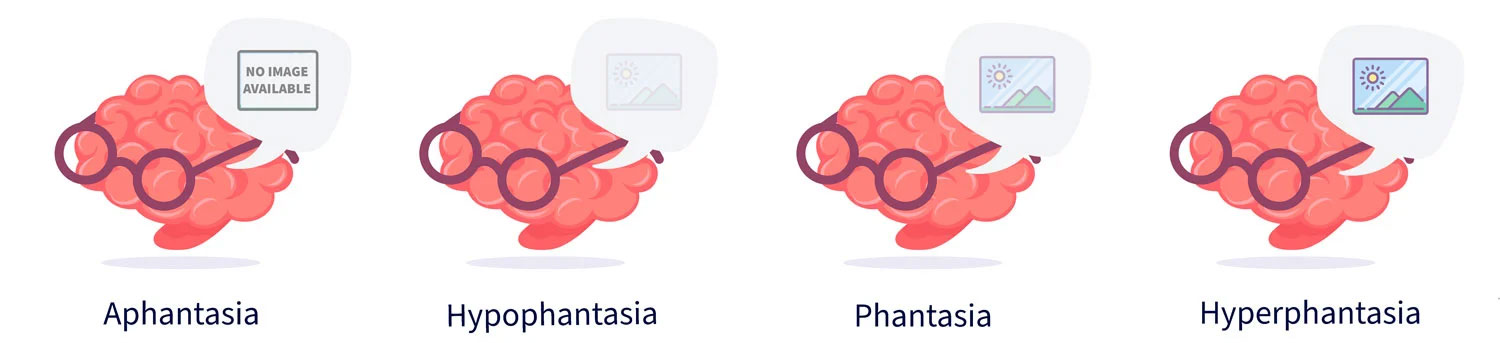

Six years ago, Meng discovered that he has aphantasia, a disorder that prevents individuals from creating mental images. The little-known condition affects an estimated 4% of the global population. Most are unaware they have it until they reach their teens or 20s, like Meng, who was 21 when he first came across the condition — known in Chinese as xinmang, or “heart blindness” — in a discussion on social media.

On Oct. 8, a new clinic opened in Shanghai that aims to identify children with spatial imagination issues and provide training that could mitigate the effects of disorders such as aphantasia. However, with the clinic’s name linking spatial difficulties with poor math skills has led to a backlash from those who fear that children diagnosed with the condition could face prejudice.

Parental anxiety

News of the world-first Spatial and Mathematical Learning Difficulties Clinic at the Shanghai Children’s Medical Center quickly spread online, with appointments in the first month fully booked within hours. Its doctors Ma Xiquan and Zhao Binglei told Sixth Tone that they hadn’t anticipated such overwhelming demand.

The clinic handles up to eight appointments every Tuesday morning. Each child undergoes a 30-minute diagnostic session, followed by several hours of cognitive assessments. Once a case is confirmed, the doctors will devise a spatial cognition training program for the patient lasting three to six months involving puzzles, physical exercise, and augmented-reality and virtual-reality tools.

Results over the first two weeks have been mixed. Despite the condition’s rarity, Ma and Zhao were able to confirm one case of aphantasia on their first day, but they also discovered that most parents were only bringing their children to the clinic in the hope of improving their math scores, with some even traveling from out of town. Meanwhile, critics took to social media to accuse the clinic of fueling anxiety by suggesting that being poor at math is a “disease.”

According to Ma, the purpose of the clinic is to raise awareness and promote an accurate understanding of aphantasia and spatial imagination difficulties. “Once we realize that a child may have this issue, we can better help them, instead of causing anxiety by making them feel they’re not trying hard enough or labeling them ‘stupid,’ as this can cause significant psychological distress,” he says.

Zhao, an assistant researcher at Shanghai Jiao Tong University’s Institute of Psychology and Behavioral Science, has co-authored studies with Adam Zeman, the expert who coined the term “aphantasia” in 2015. She explains that there is a link between visual-spatial deficits and math learning, as both rely on the same critical brain region: the intraparietal sulcus. However, poor academic performance does not necessarily indicate a learning disorder. Data cited by Zhao suggests only around 3% to 6% of children have a math learning disability, such as those affecting calculation, reasoning, or spatial imagination.

Yet, the doctors acknowledge there is a tendency among Chinese parents to overreact when their children are struggling in school. Zhao says she even received a call from a mother of a 2-year-old who asked if they should make an appointment at the clinic.

Ma and Zhao met with six patients on the opening day, and four more the following week. Apart from the confirmed aphantasia case, only one other child had possible spatial imagination issues. The rest displayed typical symptoms of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) or were simply victims of their parents’ anxiety regarding academic performance. “The ADHD cases were referred to other, more specialized clinics,” says Ma.

‘No shame’

With research into visual-spatial deficits still in its infancy, there are no known cures for conditions like aphantasia. Ma and Zhao also concede that, at this point, they are unsure what effect their training programs will ultimately have on patients.

As it’s a children’s clinic, Meng is too old to receive treatment there. However, he’s confident that its two doctors will eventually see results. Since 2018, based on information he’s gathered from forums and academic research, he’s been using building blocks and puzzles to train his brain, which he feels has had a positive effect. He’s also taken part in experimental studies for aphantasia patients.

He says he used to feel “extremely frustrated” about life, but after learning about aphantasia, he was relieved. “It turns out there are many people like me out there.”

After struggling in high school, Meng failed the first time he took the gaokao, China’s university entrance exam, in the eastern Jiangsu province. He eventually passed two years later and was enrolled at a vocational school, where he initially studied optoelectronics, the application of light-emitting and light-detecting devices, before transferring to a liberal arts program.

According to a 2020 study by Zeman, it’s extremely common for people with aphantasia to pursue careers in STEM — science, technology, engineering, and mathematics — particularly in fields that don’t require visualization skills. He surmised that this could be because these individuals often excel in expressing things in words and numbers that most people can imagine but not describe clearly.

Long term, Ma says there needs to be more policy support in China for children with learning disabilities such as visual-spatial deficits. In some countries, schools and universities allow affected students extra time with coursework and exams, and provide them with “quiet spaces” on campus.

Zhao also emphasizes the need to improve screening standards for aphantasia and to push authorities to define its medical diagnosis. “Aphantasia is still in its early stages and has not yet been incorporated into our clinical diagnostic criteria,” she says, adding that although widely recognized surveys can help screen for visual-spatial deficits, doctors in China can only make diagnoses about math disability based on standards laid out in health manuals such as the World Health Organization’s International Classification of Diseases and the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders.

Scholars worldwide have also called for aphantasia to be viewed as a neutral neurodivergence — the idea that people experience and interact with the world in different ways, with no single “correct” way to think, learn, or behave — rather than a “potentially harmful” disorder.

Since around 2022, new “learning difficulties clinics” have been gaining popularity in major cities like Beijing, Shanghai, and Hangzhou, capital of the eastern Zhejiang province. These centers primarily treat children with ADHD and provide IQ testing.

While many parents in China remain hesitant to test their children or put them on medication after a diagnosis for fear that they will be viewed differently, others are unafraid of stigmatization. A mother in Shanghai told Sixth Tone that she took her 10-year-old daughter to a learning difficulties clinic after a teacher remarked on her lack of concentration in class and low grades. Tests revealed that the girl had a lower-than-average learning ability.

“My daughter was resistant and didn’t want to go. She thought that going to a hospital meant that she was sick,” the mother says. “I explained that it didn’t mean she had a problem, just that everyone had different abilities. Understanding your ability level isn’t a bad thing; it can help you learn more effectively.”

She adds that the test results also helped her develop a “calmer attitude” toward her child’s education. “Children need to know that there’s no shame in struggling with academics. They can excel in other areas.”

(Due to privacy concerns, Meng Xingchen is a pseudonym.)

Editor: Hao Qibao.

(Header image: Visuals from SW Photography and Bruno Fernandes da Silva/VCG, reedited by Sixth Tone)