Her Dog Was Poisoned. Now She’s Fighting to Reform Pet Laws in China.

Four days after the Mid-Autumn Festival in 2022, Li Yihan took her 13-year-old dog Papi for their usual morning walk. Hours later, her mother called with devastating news: Papi was twitching uncontrollably and might not make it.

By that evening, her West Highland White Terrier was gone — one of 11 dogs and several stray cats poisoned in their Beijing neighborhood over the course of two days starting Sept. 13.

Police investigations later revealed that a 65-year-old resident surnamed Zhang had deliberately placed poisoned food. He had soaked chopped chicken neck bones in fluoroacetic acid and put them near the community children’s playground, targeting pets that frequented the area.

While other pets died within minutes of ingesting the toxic bait, Papi clung to life for nearly three hours. For 35-year-old Li, the pain of losing Papi has only been worsened by a long, frustrating wait for justice.

Despite Zhang’s swift arrest, the verdict has been repeatedly delayed since the trial began in October 2023. While Chinese criminal law mandates a verdict within three months, extensions for civil lawsuits and further investigations have stretched the case beyond two years. Last month, the court postponed the decision for the fifth time.

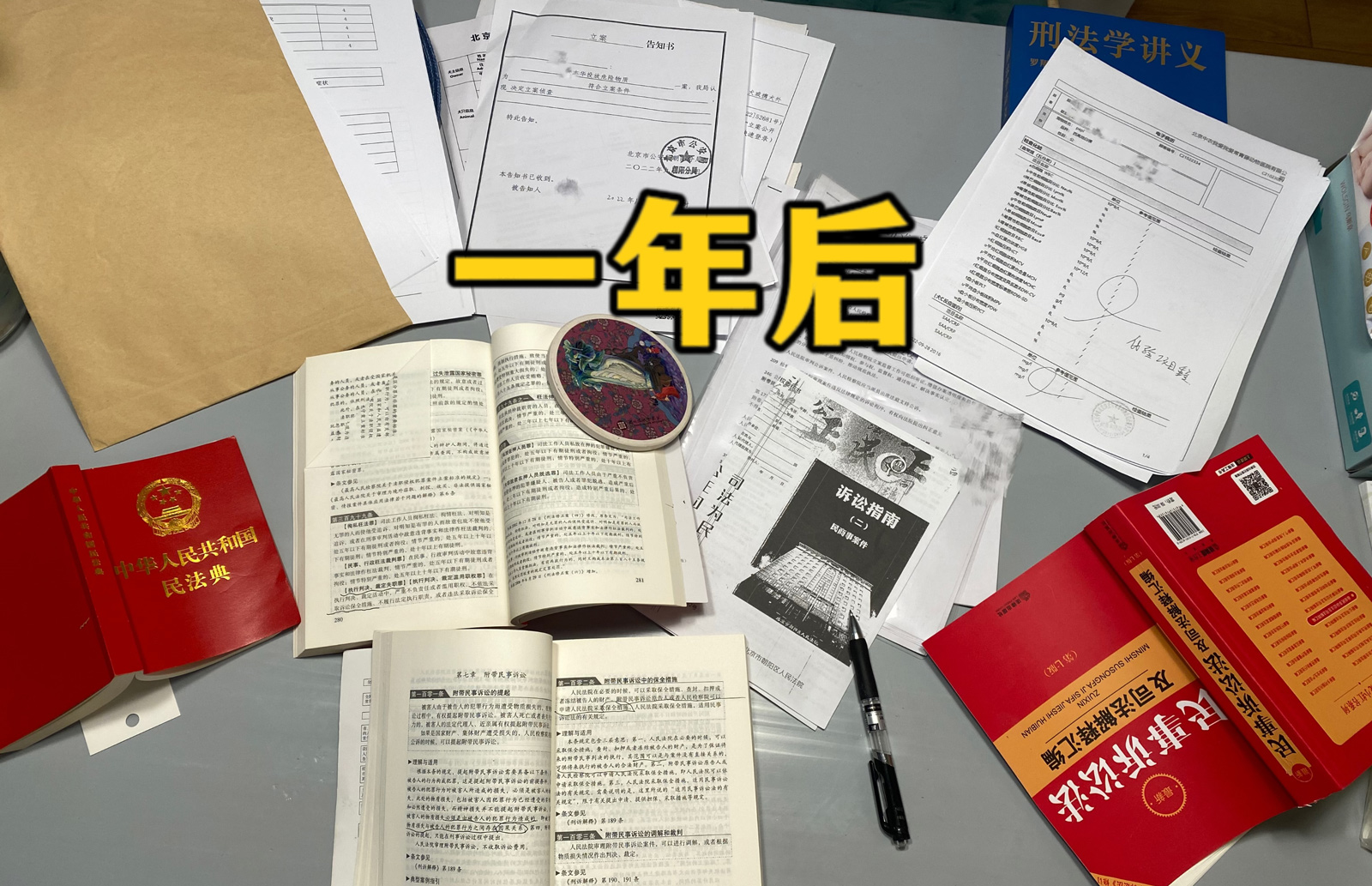

The delays have only fueled Li’s resolve. After Papi’s death, she quit her high-paying job as a film producer and dedicated herself fully to the case. Immersing herself in criminal law, she learned the statutes, consulted lawyers, and gathered evidence — even convincing the other affected pet owners to join her in pursuing civil suits alongside the criminal trial.

Li hopes her campaign will raise awareness and push for stronger legal protections for animals across the country. Her efforts go beyond personal grief — Papi’s case is now Beijing’s first criminal trial over pet poisoning based on public records.

The outcome could set a precedent for how future animal cruelty cases are handled. “This case has gained attention as the first-known criminal trial for poisoning pets in the capital,” says Huang Xueshan, a lawyer from Landing Law Offices who has handled numerous pet-related cases. “It can serve as an example for pet owners, many of whom don’t realize they can file civil lawsuits alongside criminal proceedings.”

As similar poisoning cases continue to surface across China, the lack of comprehensive laws leaves companion animals vulnerable. This past May, over 20 dogs were poisoned to death in Beijing’s Fengtai District. The same month, two Border Collies were killed by a neighbor in the northern Hebei province after a dispute over barking. And in October 2023, at least five dogs in the southwestern city of Chengdu were similarly poisoned.

Many cases never make it to court, as the value of poisoned pets is often deemed too low to warrant legal action, or the poisoning doesn’t cause public harm. Criminal cases like Li’s remain rare.

“The existing legislation is certainly inadequate to deter pet-related crimes,” says Huang. “The introduction of specific criminal laws targeting such acts against pets could significantly raise awareness of the consequences and deter similar actions by increasing the perceived cost of breaking the law.”

The prolonged legal battle has taken a severe mental toll on the 11 pet owners, especially Li, who has been diagnosed with severe depression and anxiety after losing Papi.

But she’s committed to the case, sharing frequent updates on social media, where her fight for justice has drawn significant attention. A hashtag, “Speak up for the West Highland White Terrier Papi,” has garnered over 4 million views on the lifestyle app Xiaohongshu. And on Douyin, China’s version of TikTok, videos with a similar hashtag have over 37 million views, with many hailing Li as a role model for animal protection advocacy.

However, Li has also faced backlash including online harassment and hurtful comments questioning her motives. Yet, for the past nearly 800 days, her mission has been clear: to seek justice for Papi.

“Some people say I’m great, brave, and that my light will shine on others, but I just see myself doing what I’m supposed to do,” says Li, who spoke to Sixth Tone using a pseudonym to protect her privacy. “I’m fighting for justice for my child, that’s all.”

Darkest day

In early 2010, just after the Spring Festival, Li found her “dream dog” in a Beijing pet store. Out of all the puppies, the 2-month-old West Highland White Terrier’s lively energy and mischievous nature immediately caught her eye.

“He was so tiny, no bigger than my palm, and his ears hadn’t even stood up yet, which made him look like a little stray,” says Li, adding that she named him Papi after a favorite character from an American TV show.

As a first-time pet owner, Li was diligent about Papi’s care, from daily routines like tooth cleaning and meal preparation to regular vet checkups. “People always thought he was 2 or 3, but he was almost 13,” says Li.

Over the next decade, Papi became Li’s constant companion through life’s milestones: graduating from university, falling in love, and landing her first job. He was there through all her highs and lows, triumphs and disappointments.

“Perhaps a little dog is inherently the best kind of healing medicine,” says Li. “I raised him, and he nurtured me emotionally. For me, he was an irreplaceable part of my life.”

In 2021, Li moved to a new community because it offered a rare dog-friendly park, something hard to find in urban Beijing. But as Papi aged, he preferred the softer plastic track in the communal area over the grass. “I hoped he would live to at least 20,” Li says.

On Sept. 14, 2022, Li took Papi for their usual 15-minute walk on that track. Afterward, she fed him a simple breakfast of dog food and broccoli before heading to work — it would be his last.

Later that morning, Li received a message from another pet owner warning that dogs in the community were being poisoned. Shocked but not overly concerned, Li dismissed the thought — Papi had just eaten breakfast and seemed fine. Still, she called the property management office to alert them.

She received a frantic call from her mother at noon. Papi was twitching uncontrollably, screeching, and losing control of his bladder and bowels. Panicked, Li tidied her desk and rushed to the nearby pet hospital, realizing she might not return to work for quite some time.

There, Papi had already been heavily sedated to stop his violent seizures. The vet recommended transferring him to a larger facility for more advanced treatment, including hemodialysis to filter the poison from his system.

Despite the high cost — tens of thousands of yuan with no guarantee of success — Li didn’t hesitate. Too weak to carry Papi herself, she watched as the doctor gently placed him into the car for the transfer.

“I was just holding the respirator because he couldn’t breathe on his own after being poisoned,” says Li. “His tongue had already turned black, and it was just pressed against the roof of his mouth.”

At the new hospital, another dog from her community was undergoing the same treatment, but it failed, and the dog died within minutes. “I stood there, watching like it was a silent movie,” says Li, remembering how the other dog’s family wrapped their pet in a blanket and left the hospital in tears.

Still, Li hadn’t given up hope. After the hemodialysis, Papi showed a brief glimmer of life, managing to throw up his breakfast. Li encouraged him to keep fighting, but she could see the light in his eyes slowly fading. By 7:10 p.m., Papi was gone.

Since it was too late to arrange a funeral service that night, Li took the body home. “A dog feels heavier after death, similar to carrying a person who’s passed out,” says Li, her voice thick with the memory of that cold autumn evening.

No turning back

That night, sleep was impossible. Li’s mind raced with just one thought: justice for Papi. Knowing the road ahead would be difficult, she spent the entire night piecing together a video of Papi’s final moments, every frame a painful reminder of her loss.

She posted it online, hoping to rally public support and draw attention to the tragedy. “While editing the video, I kept telling myself it was someone else’s story, not mine,” she says. “Otherwise, I wouldn’t have been able to do it — my hands were shaking, and my eyes were filled with tears.”

The video amassed over 16,000 likes, with many voicing support for Li while condemning the heinous act.

Over the past two years, Li has posted over 500 short videos on Douyin, updating her almost 60,000 followers on the case and attracting millions of views. Despite her devotion, many — including her own family — struggle to understand the depth of her commitment. “Maybe if people imagined him as a 13-year-old boy, they could empathize with me,” she says. “But I don’t need their empathy.”

Li’s objectives have evolved beyond seeking justice; she’s determined to raise awareness about the gaps in China’s legal system when it comes to protecting pets.

While the country has laws to safeguard wildlife, livestock, and laboratory animals, there’s no comprehensive legislation for companion animals like cats and dogs, explains Qian Yefang, a law professor at Zhongnan University of Economics and Law in the central Hubei province.

“The current animal protection laws on the mainland are fragmented and incomplete, lacking a cohesive system, and the legal responsibilities aren’t strict enough,” Qian told domestic media in 2023.

Without such laws, pet poisoning is not classified as a specific crime in China. Incidents like these are difficult to prosecute unless they pose a threat to human safety or result in significant property damage.

“If it doesn’t affect people directly, it’s difficult to prosecute,” adds Huang Xueshan, the lawyer who has handled pet-related cases. The challenge is even greater when poisons are used in low-traffic areas or target stray animals.

When police discovered fluoroacetate — a banned toxic substance often found in rat poison — in some of the dogs that died in Li’s community, police upgraded the case against Zhang from a civil dispute to a criminal investigation. Zhang was charged for spreading poisonous substances that endangered public safety.

According to Li, Zhang targeted pets because he was angry about dogs urinating on his tricycle and his granddaughter’s dislike of them.

Though the suspect may not have intended to harm people, Huang explains that his actions still posed a clear threat to public safety, making him criminally liable. Under Chinese law, spreading poisonous substances that endanger public safety carries a prison sentence of three to 10 years if no serious harm occurs.

Before the criminal trial began, Li also persuaded other affected pet owners to join her, forming a group of 11 plaintiffs to pursue civil suits alongside the criminal case. “Convincing each family was time-consuming, but I had to do it because I want to win,” Li says. “The strength of 11 is much greater than one alone.”

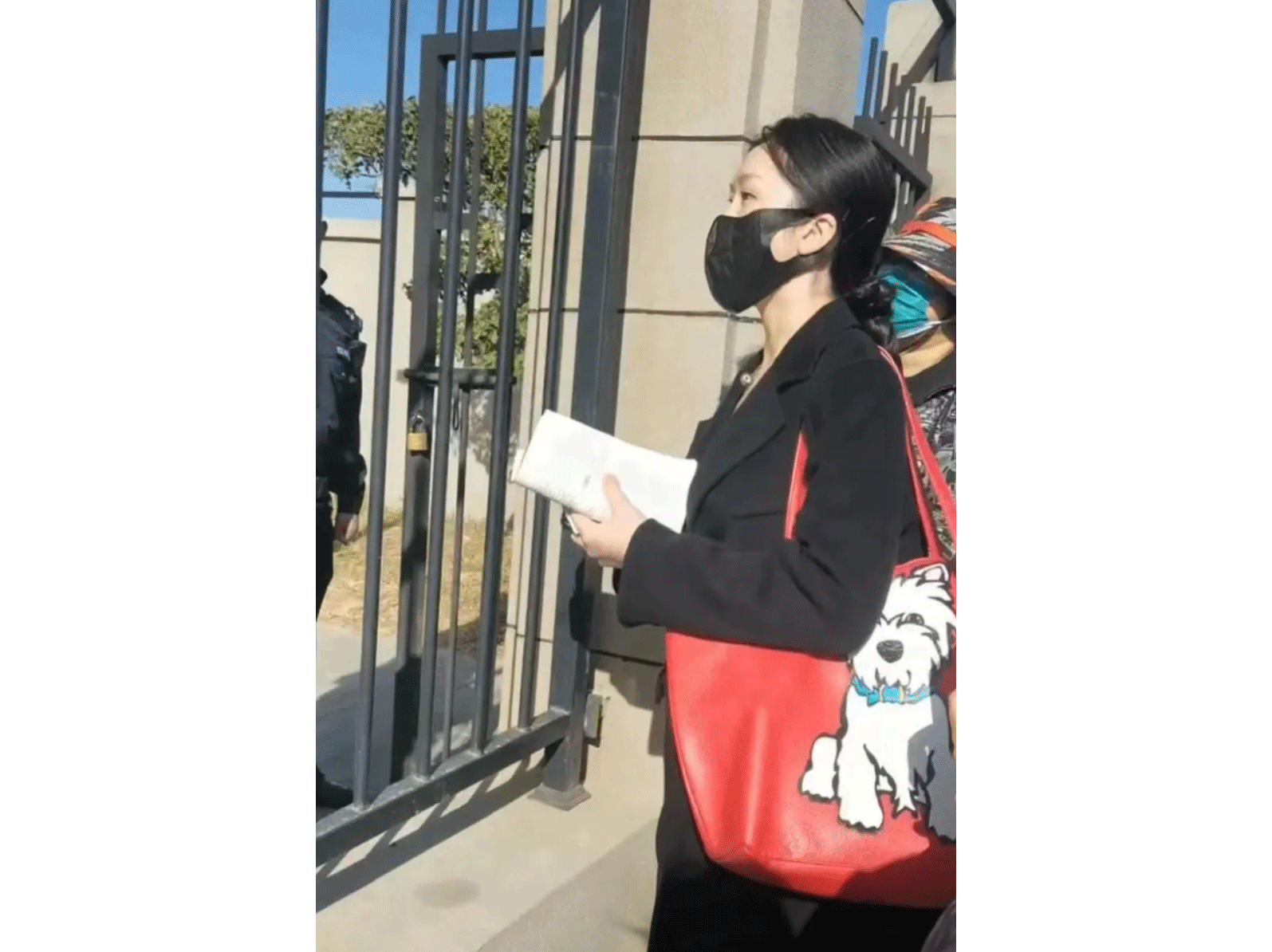

On Oct. 26, 2023, the case went to trial at the Chaoyang District People’s Court in Beijing, with all 11 plaintiffs present. Li sat almost face to face with Zhang.

When he entered the courtroom in prison uniform, handcuffed and shackled, Li trembled with anger but forced herself to stay calm. “If I stared at him too long, I don’t know what I might’ve done,” she recalls.

Though Zhang admitted guilt and apologized, his legal team rejected all compensation claims from the plaintiffs, dismissing their demands as irrelevant.

Under China’s Civil Code, pet owners can seek compensation for mental suffering if the loss of a pet causes significant emotional distress. However, Huang underscores that the ruling depends on the judge’s interpretation of “personal significance” and the evidence presented.

With 11 civil suits tied to the criminal case, the court has yet to announce a verdict. Huang believes a prison sentence is likely, but its length will depend on the court’s evaluation of Zhang’s actions and remorse.

In recent years, China’s courts have sentenced pet poisoners to prison. In 2019, a man in the northern Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region received three years and six months in jail for poisoning eight dogs. In 2021, another man in the eastern Shandong province was sentenced to three years, with four years’ probation, for poisoning two dogs. And in 2022, two men in the northeastern Heilongjiang province were sentenced to over three years each for poisoning 11 dogs.

While these perpetrators reached settlements with the victims’ families, Li says Zhang and his family have shown no willingness to settle since the incident.

While waiting for the verdict, Li hasn’t left Beijing since the first trial, afraid of missing any important updates. “The poisoner has been in the detention center for almost two years, and I feel like I’m locked up with him,” she says.

Courting change

Li believes the verdict will hinge on three factors: the amount of poison Zhang used, the banned substances found at his home, and the pets’ appraised value.

Determining the value of Papi and the other pets has been especially painful for Li. In China, pets are considered property and assessed by market value. Without pedigree papers or proof of purchase, appraisals become even harder, and most companies Li contacted didn’t know how to handle pet valuations.

“Legally, pets aren’t considered family members, and that already hurts. What’s worse is that, unlike other property, it’s much harder to get compensation when they’re harmed,” says Li. “If my car were damaged, I wouldn’t be waiting two years for compensation.”

Pet ownership in China has surged, with data from 2023 showing 51.75 million dogs and 69.8 million cats. Animal protection laws, however, have lagged behind those in countries like the UK and US, says Zhou Ke, a law professor at Renmin University.

Growing awareness has sparked efforts to improve legislation. In 2010, experts proposed an anti-cruelty law, and by 2020, dogs were reclassified as “companion animals” rather than livestock.

Huang says the foundation for pet welfare laws exists, but progress depends on public demand and high-profile cases like Li’s. “Cases like this one build momentum for new legislation,” she explains, adding that current regulations often focus more on control than protection.

Back in Beijing, Li has adopted a cat and started learning livestreaming e-commerce to make ends meet as her savings dwindle. She’s also authorized a Beijing-based film company to adapt her story for the screen.

While recent months have been filled with screenplay meetings, the project offers a rare respite from the constant cyberbullying and negativity surrounding the lawsuit.

“It helps me channel my focus elsewhere, but it’s also overwhelming at times,” Li admits. “For the past two years, I’ve felt like a one-woman army, trying to do everything on my own.”

Though the film is still in its early stages, Li holds hope for what it could become. “For others, this may just be another project, but for me, it’s everything — the blood, sweat, and tears I’ve poured into this fight. The outcome is uncertain, but I’ll take it one step at a time, just as I’ve done with everything else,” she says.

Editor: Apurva.

(Header image: Courtesy of Li)