Gold Testers: How a Fake Review App Hacked China’s Shopping Platforms

A few days ago, Shanghai-based retiree Zhao Li received a phone call that left her profoundly shocked. The caller said they were a vendor on a popular Chinese shopping app, and they had an unusual offer for her.

All the 68-year-old had to do was place an order for a pair of shoes priced at 199 yuan ($28), then place a product review provided by the vendor on the app. As soon as she’d copy-pasted the text and images, the vendor would refund her purchase and pay her a 10-yuan commission.

For Zhao, it was an eye-opening moment. Ever since she learned to use e-commerce apps during the pandemic, she had been buying nearly everything online, carefully checking the product reviews before each purchase. But now she realized that many of those reviews were probably fake.

Thinking back, all her recent frustrating purchases made sense. The bath towel that was praised in the review section for being highly absorbent, but turned out to hardly absorb any water at all. The highly-rated down jacket that arrived wrinkled and poorly made.

“I started to carefully examine those reviews, and noticed that many of them used very similar wording,” Zhao told Sixth Tone. “This has left me very confused about how I should judge the quality of an item in the future.”

Zhao had become just the latest victim of China’s fake review industry — a cluster of shady companies that have managed to influence the country’s top e-commerce platforms on a staggering scale over the past few years.

On Monday, an investigation by state broadcaster CCTV revealed that an entire gig economy focused on fake reviews has emerged, with platforms hiring vast armies of part-time workers to post billions of fabricated product reviews on their clients’ online stores.

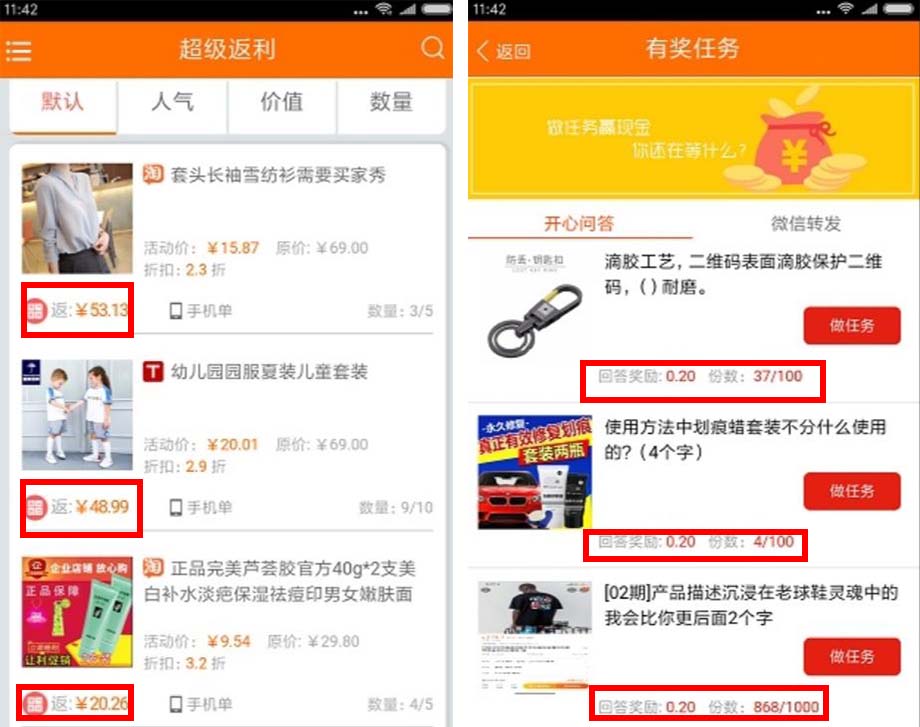

The investigation focused on an app called Gold Testers that functions similarly to a gig economy platform like Taskrabbit. Anyone can sign up and begin working as a fake product reviewer, receiving a small commission each time they post a review.

In the CCTV report, a police officer from eastern China’s Zhejiang province demonstrates how the system works. The officer describes how, just like Zhao, the reviewer places an order and then posts a pre-prepared review — including images and text — on the client’s online store. Then, the reviewer receives a full refund and a 5-yuan commission.

Since it launched less than three years ago, Gold Testers has expanded at a blistering pace. The app has reportedly worked with more than 36,000 e-commerce vendors and over 600,000 reviewers, who have generated over 200 million fake product orders with a total transaction volume of around 4.7 billion yuan.

Gao Chengxuan, a cybersecurity officer also from Zhejiang province, told CCTV that many group chats on Chinese social media spread advertisements for Gold Testers, encouraging people to sign up as fake reviewers.

“There are no real barriers to becoming a fake reviewer,” he said. “As long as you can use a phone, you can complete the task with just a few taps and earn commissions or a small gift.”

Gold Testers isn’t the only player in this space. In March, a WeChat mini program called Star Team also made headlines for recruiting an “internet water army” to post fake reviews. Since 2022, the group had reportedly placed fake orders and reviews for over 1,000 vendors on various e-commerce platforms, with a total transaction volume of over 100 million yuan.

CCTV’s report did not reveal what action police had taken against Gold Testers, but a Sixth Tone search on Monday found that the app was unavailable on the Apple App Store and the main Android app stores used in China.

China has ramped up efforts to clamp down on so-called “cyber armies” flooding platforms with fake content in recent years. But new groups keep emerging due to the lucrative profits they can often earn.

Luo Meng, a researcher at Zhejiang University’s School of Cyber Science and Technology, told CCTV that cyber armies tend to be large-scale, but highly mobile and well-concealed, making them difficult to police.

“Especially in recent years, with the development of various emerging technologies and the technical support provided by the cyber army industrial chain, they can quickly conduct and disseminate marketing content,” said Luo. “This poses significant challenges to law enforcement.”

Luo emphasized that winning the battle against cyber armies would require more action by both regulators and platforms. Regulations surrounding cyber armies are still weak and vaguely defined, and tech companies could do more to detect and remove illegal activities on their platforms, she said.

(Header image: VCG)