Lost and Found: Seeking Solace in Street View Snapshots

Two years after her mother’s death, Yu Jia discovered a random snapshot of her online — a fleeting moment captured by a “street view” car while it collected data for a Chinese navigation app. She’s in a floral blouse and jeans, and holding an umbrella.

Writing about the discovery last year on the social media platform Xiaohongshu, Yu imagines her mother must have been rushing back to work after a quick hair appointment during her lunch break. “Is it going to rain this afternoon? I see you’ve brought an umbrella. Did you have a proper lunch, or just a snack?” she asks in her post, which appeared to deeply resonate with fellow users, attracting 9,000 likes and many comments about similar experiences.

In recent times, the street-level images offered up by various navigation apps have become accidental time capsules, preserving touching memories of lost loved ones, demolished homes, and forgotten childhoods.

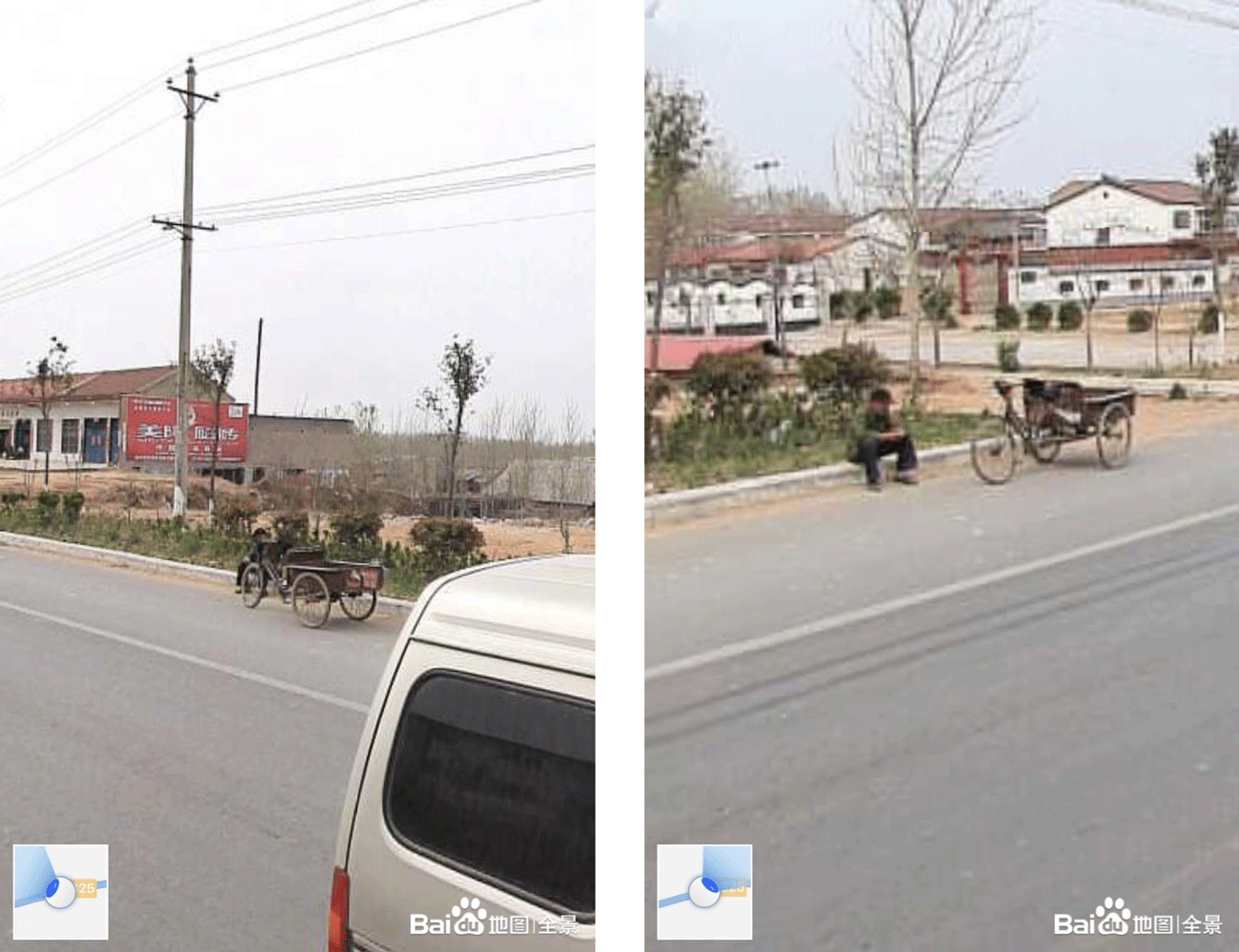

Lin Li was working in Shanghai in 2018 when her father passed away suddenly in Kaifeng, in the central Henan province, before she could return home to say a final goodbye. When she read online about the “street view phenomenon,” with netizens reporting that they’d spotted deceased relatives in images captured around their homes or places they visited frequently, she decided to try her luck. Using the Baidu Map street view function, she revisited Kaifeng before 2018. There, she found her father beside an asphalt road connecting her hometown with the county seat, near a plaza where he often shopped.

The image was taken in late fall; the sky is overcast, and the only vibrant colors are the evergreens along the street. A man is sitting hunched by the roadside. His face is blurred, but Lin recognized him immediately from his typical Zhongshan suit — a tunic suit popular among China’s older generations — and military-style cap. It was just a 10-minute bike ride from his home to the grocery store, but he’d stopped halfway, perhaps to take a rest. “He was actually tired sometimes,” Lin realized for the first time. The image contradicted her earlier impression of the man, who, although thin, had always seemed strong and healthy.

Next to her father is his old tricycle, a faithful companion of nearly 20 years. Memories surfaced of Lin’s boarding school days, when her parents would visit her dormitory, bringing homemade dumplings and stewed meat. As her mother’s mobility declined, it was her father who rode the tricycle to pick her up. Though their neighbors had switched to electric bikes, her father stuck with his pedal-powered model, fearing that his occasional brain fog in old age might cause him to confuse the accelerator with the brake. In 2020, Lin returned home to find that her mother had sold the tricycle. “Only after these cherished childhood relics disappear do we realize we’ve grown up,” she says. When she began working as an architectural engineer in Shanghai, she would often respond impatiently to calls from her parents, not for one second anticipating her father’s sudden death. Shortly before he passed, she had missed his final call.

Staring at the image of her father by the roadside, Lin’s memories came flooding back. He had been an eccentric yet warmhearted man, often helping his neighbors install doors and windows. He loved to cook, and would experiment with the recipes he saw on television. His signature dishes included fried noodles, sweet and sour green peppers, and steamed noodles with green beans. Lin also recalled when the family dog went missing, he took her on his tricycle to search villages up to 10 kilometers away.

These virtual street view tours also stirred up deep-buried emotions. Lin recalled that, after starting middle school, she felt like her 60-year-old father had been replaced by a stranger. He stopped cooking, and when he occasionally did, he would only boil chicken without any seasoning. During wheat harvests, he used to carry the loads himself, but he began to rely on his wife’s help, and eventually let her do it all alone. Lin used to think he was being lazy. Now, at nearly 35, she finally understands how age can sap one’s energy — a realization that has brought her a deep sense of guilt, especially after hearing her mother’s account of his passing at 75. He was eating breakfast as usual, but felt a little unwell. By the time Lin’s mother returned with some medicine, he was already in his last moments. “It was sudden, hard to explain,” she says.

Working away in a big city, Lin’s connections with her parents had been reduced to reunion dinners at Spring Festival, the Chinese New Year and brief, repetitive phone calls every two weeks: work comes first, take care of yourself, eat well. Her mother’s car accident, the hospital stitches, her father’s hip fracture — Lin learned of all these incidents only after her father had died. His digital representation on an online map was the only witness to his aging.

Time capsules

When Qiao Ping from Beijing decided to use a navigation app’s street view function to find her family’s old house, which had been demolished six years earlier, she was still grieving the loss of her father from liver disease. Insomnia had driven her to obsessively search his symptoms online, wondering if a different hospital might have saved him. Searching with the keywords “father’s death,” she found many others also struggling to accept their losses. One comment struck her deeply: “The loss of a loved one leaves a permanent dampness in the heart.” Her frequent searches soon saw big data pointing her toward finding a lost loved one in street view images.

Her journey began at the village bus stop, following a route home she had walked for over 20 years, and her father for more than 40. Houses in her village had no numbers, so she could only retrace her steps, passing the bustling marketplace and the small shop where her father would sometimes sneak a drink. “Please, let him be there,” she prayed silently.

When he wasn’t inside the shop, Qiao kept clicking through the map, inching closer to home. Finally, after what felt like an eternity, she saw him — he was standing outside their old brick house, wearing a red jacket and sweatpants. Her heart tightened. “I felt grateful to find another picture of him, but the sadness hit me right away,” she says. “I pretended everything was fine at my desk, then rushed to the bathroom to cry.”

Now, both the house and her father are gone. Upon the demolition, the family returned to the site only to find that the sole reminder of their past life was a note Qiao had left on the front door as a child about her favorite TV shows. The house had been her refuge before she went to university, but she had never thought to take a photo.

Qiao’s father was admitted to hospital at the end of 2022. Because of the strict pandemic control measures, she and her mother could only communicate with him through video calls from outside the ward. When his phone ran out of battery, which happened each day, they would ask the nurse to recharge it. But he didn’t hold on for long. He was only 48 when he died. Six months earlier, he and Qiao’s mother had moved into a new home. She vividly remembered her father’s comment when he discovered it had central heating: “Winter will finally be warm.”

The map images triggered a wave of recollection. Along that well-trodden path home, Qiao had, on separate occasions, lost her bus pass, been hit by a bicycle, and had to sprint down a dimly lit alley in fear. In the image of her father, he’s standing next to an old reclining chair where they used to sit together, wrapped in a blanket, watching the snow and poking fun at her mother. When Qiao shared these memories on social media, one netizen commented, “At that moment you saw your father, he was looking at you too.”

Zhang Wan, from Pingdingshan, Henan, found her grandfather in one of these time capsules. He’s sitting at the entrance of their residential complex, legs crossed on a small folding stool, talking on the phone. “In that moment, I felt a rush of blood to the head, like I was connecting with my grandfather across time and space,” she recalls. After his death, Zhang had hidden away his much-loved tai chi books and handmade kites, as it was too painful to look at them. But that day, she suddenly saw her grandfather from 2014, the year she sat the gaokao, China’s college entrance exam. He had been so proud of her results, always smiling. “That street view image is a trace my grandfather left in a place none of us knew. Even if one day no one remembers him, as long as the map exists, he will always be there,” she says.

Take me home

For middle-aged people with careers, street-level images have also helped preserve the landscapes of their hometown — the fields, rivers, and houses — and allow them to take brief sojourns back to their childhood.

Gao Zepeng’s interest was instantly piqued this summer when he spotted a post in an online group chat about “viewing 360-degree images of your hometown.” The group was initially created during the pandemic for people in his village to stay in touch, and today it has more than 400 members, many of them in their 80s. Gao, 34, has lived in Qingdao, a coastal city in the eastern Shandong province, for a decade, but he likes to stay informed about goings-on in his native Liaocheng, about a five-hour drive inland.

The post linked to a mini program available through the WeChat messaging app, 720-Degree Vision of the World, which provides panoramic views of nearly 50,000 villages across China. Gao entered the name of his hometown, and its vivid landscape unfolded before his eyes — rivers, checkerboard fields, and the blue roof of his family home. Excited, he shared the link with his cousins. “I never realized how deep your connection is with our hometown,” replied one, who now lives and works in Shanghai.

Raised by his grandparents, many of Gao’s childhood memories are associated with the village — jumping rope in the summer vacation, lying on straw watching the clouds, or reciting English texts along a quiet, tree-lined road. The cicadas in the tall trees were his childhood companions, and he would fly kites and gaze at the moon. Though the big trees are gone, it remains a must-visit whenever he returns. The village was a place where time seemed to slow down, unlike Qingdao, where each day begins with a rush of work demands.

After a decade working at a private company, Gao feels stuck in a rut. Early on, business travel felt like an exciting way to see the world, but now, as a mid-career worker, constant workplace changes and urgent tasks only disrupt life’s rhythm. Every time a holiday ends and he boards the train back to the city, a sense of sadness descends. In his mind, home has become the ideal workplace, and he sees the people running small businesses there as the happiest workers. “They have a great work-life balance, with little stress,” he says, although he knows that working remotely from his hometown is more of a dream scenario than a possibility. When Gao shared his plight with his cousin, he responded with similar stories of burnout and a desire to return home. Gao could understand his cousin’s situation — two daughters and a mortgage left him with no easy way out.

For Li Yuning, who works in Wuhan, in the central Hubei province, virtual images of her hometown weigh heavy on the heart, as she feels not a single place or piece of clothing there “belongs to her anymore.”

Although she left Yulin, a city in the southern Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region, more than 10 years ago, Li has developed a habit of regularly checking images of her hometown on navigation apps. Most recently, during the Mid-Autumn Festival in September, she opened a map during an evening stroll through her neighborhood. Gazing at the moon, she reflected on celebrations when she was a child. Back then, her family would gather on their rooftop, sharing a large mooncake and watching fireworks over a nearby factory. Nowadays, her father does business in the island province of Hainan, her sister lives in the southern metropolis of Shenzhen, and her two half-brothers are in Liuzhou, Guangxi, so getting everyone together is near impossible.

Using street view, Li located her elementary school and followed the river southward. Two small roads branched off from the main road, forming a trapezoid. At its deepest point stood a house with a blue roof — her family home, where her stepmother and grandfather now live. Her father remarried when she was about 6 years old, and he had two children with her stepmother. When the blended family gathered at the dinner table, her stepmother would kick her under the table if she took an extra piece of meat. Complaining to her father would only intensify the situation, so she learned to remain silent. As she grew older, her stepmother forbade her from eating at the table, so she built a small brick stove in the yard to cook for herself.

Escaping her hometown became the theme of Li’s early life. When she was accepted into university, her stepmother gave her room to her younger brothers, meaning she had to sleep in the guest room on school breaks. The last time she returned home was two years ago, for her grandfather’s birthday. It stung when her cousin’s child pointed at Li and asked, “Who is she?” Li recalls, “It felt like I was a guest in my own family.”

Now in her 30s, Li says her life is filled with anxiety. She used to work in sales in Shenzhen, earning around 20,000 yuan ($2,800) a month, but after moving with her husband to Wuhan, they have faced challenges in the job market. Her husband started a company as a side business, but this year he accrued over 300,000 yuan in unpaid invoices. Monthly car and mortgage payments totaling 15,000 yuan keep Li awake at night. Her mother-in-law also keeps urging the couple to have children, and every discussion about it circles back to their financial burdens.

Li has never shared her map-viewing habit with her husband, who only learned about her family situation a year into their relationship. He has yet to visit her hometown — she fears a conflict might arise between him and her stepmother. Looking at the street view images, she feels like the protagonist of a video game with a mission to escape to a simpler, carefree time.

Among the virtual houses, she searches for her family’s pond. In childhood, Li and her siblings would splash in the water, and in the run-up to Chinese New Year, they would wake at four or five in the morning to haul nets and catch fish to sell. A life that once felt hard now brings her gentle, joyful memories.

(Due to privacy concerns, all interviewees are using pseudonyms.)

Reported by Lü Xucheng.

A version of this article originally appeared in White Night Workshop. It has been translated and edited for brevity and clarity, and is republished here with permission.

Translator: Chen Yue; editors: Wang Juyi and Hao Qibao.

(Header image: Visuals from VCG, reedited by Sixth Tone)