A Forgotten Book Gets a Fresh Look

Tou-Se-We Museum, located on a quiet street in Shanghai’s Xuhui District, sits atop the former site of the Tou-Se-We Orphanage. Established by Western missionaries in 1864, the orphanage trained children in skills such as painting, music, sculpture, woodcarving, and printing. Today, the museum’s collection centers around the works of art those children — including the painter Xu Yongqing and the sculptor Zhang Chongren — would go on to create.

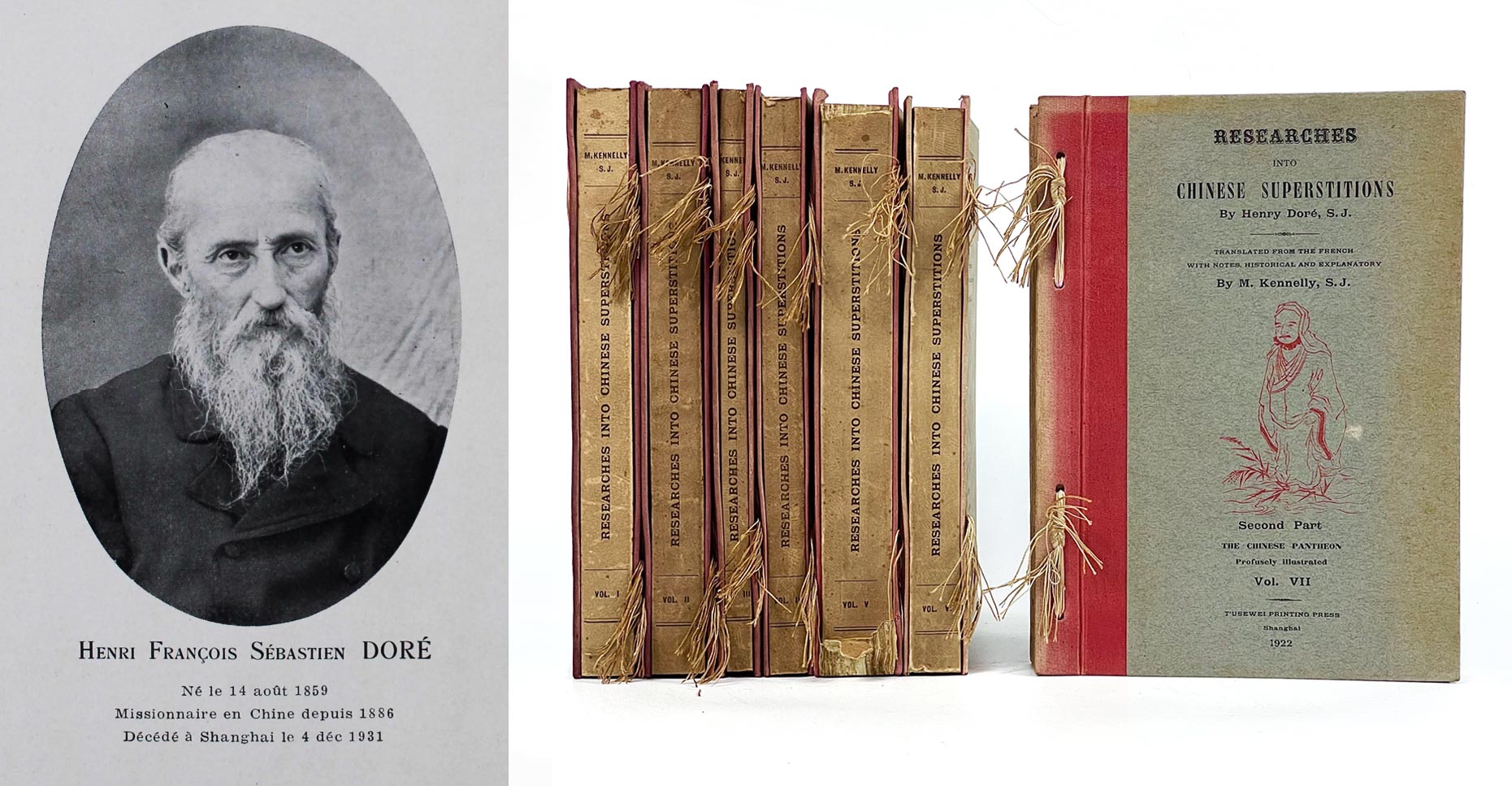

But the Tou-Se-We Museum also holds a range of important, if often overlooked documents, including a complete copy of Henri Doré’s “Researches into Chinese Superstitions” — a once-maligned series of books that has undergone a major critical reappraisal in recent years.

Henri Doré was born on Aug. 14, 1859, in Bessé-sur-Braye in western France. A Jesuit, after his training, the order sent him to its Mission de Kiang-Nan in eastern China — what is today the regions of Jiangsu, Anhui, Shanghai, and parts of Jiangxi.

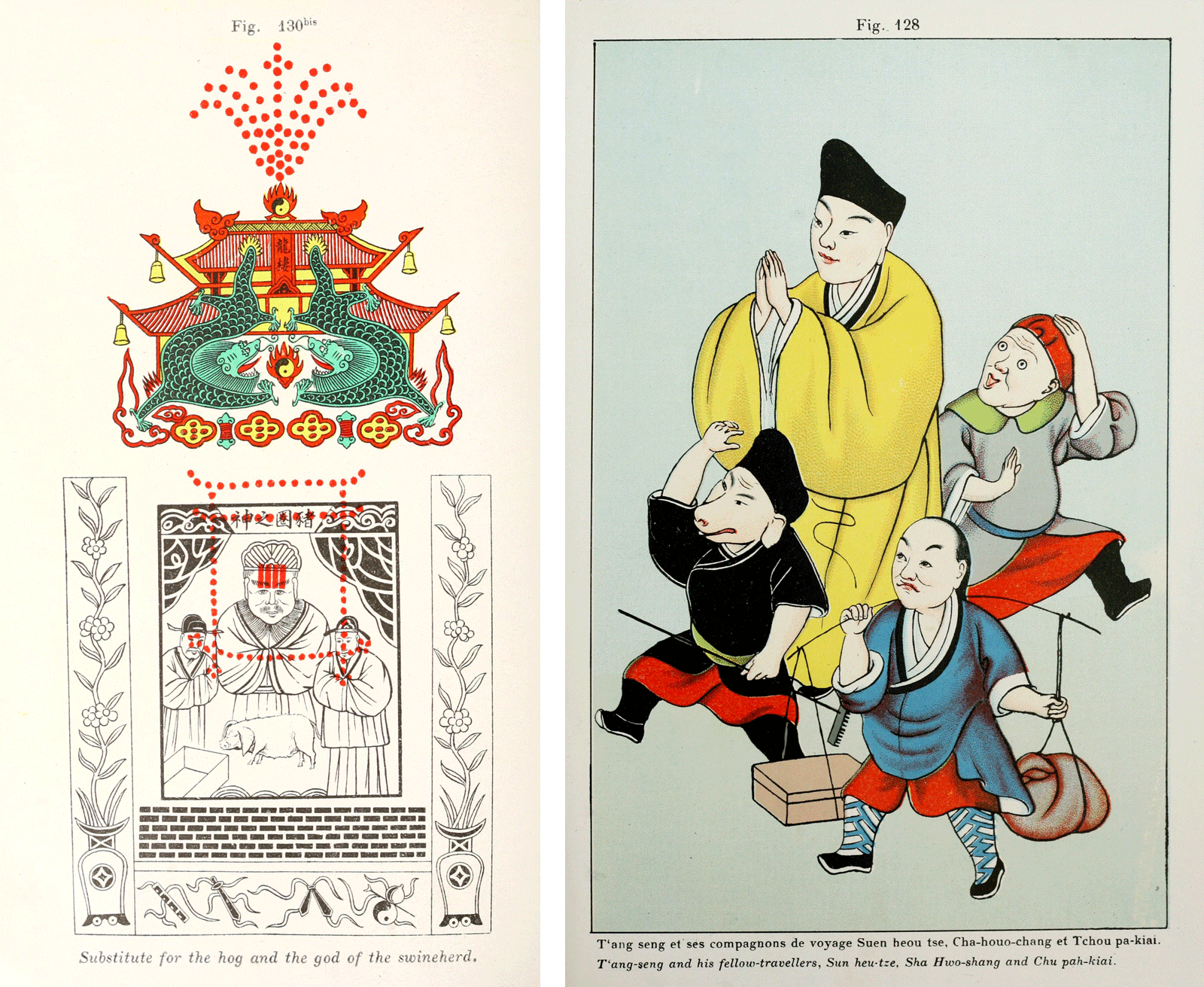

In China, Doré was responsible for procuring food and other needed goods for the church. His position meant he frequented local markets, both large and small, where he first saw and became enamored with traditional folk arts such as zhima, or “paper horses,” and nianhua, or New Year’s prints.

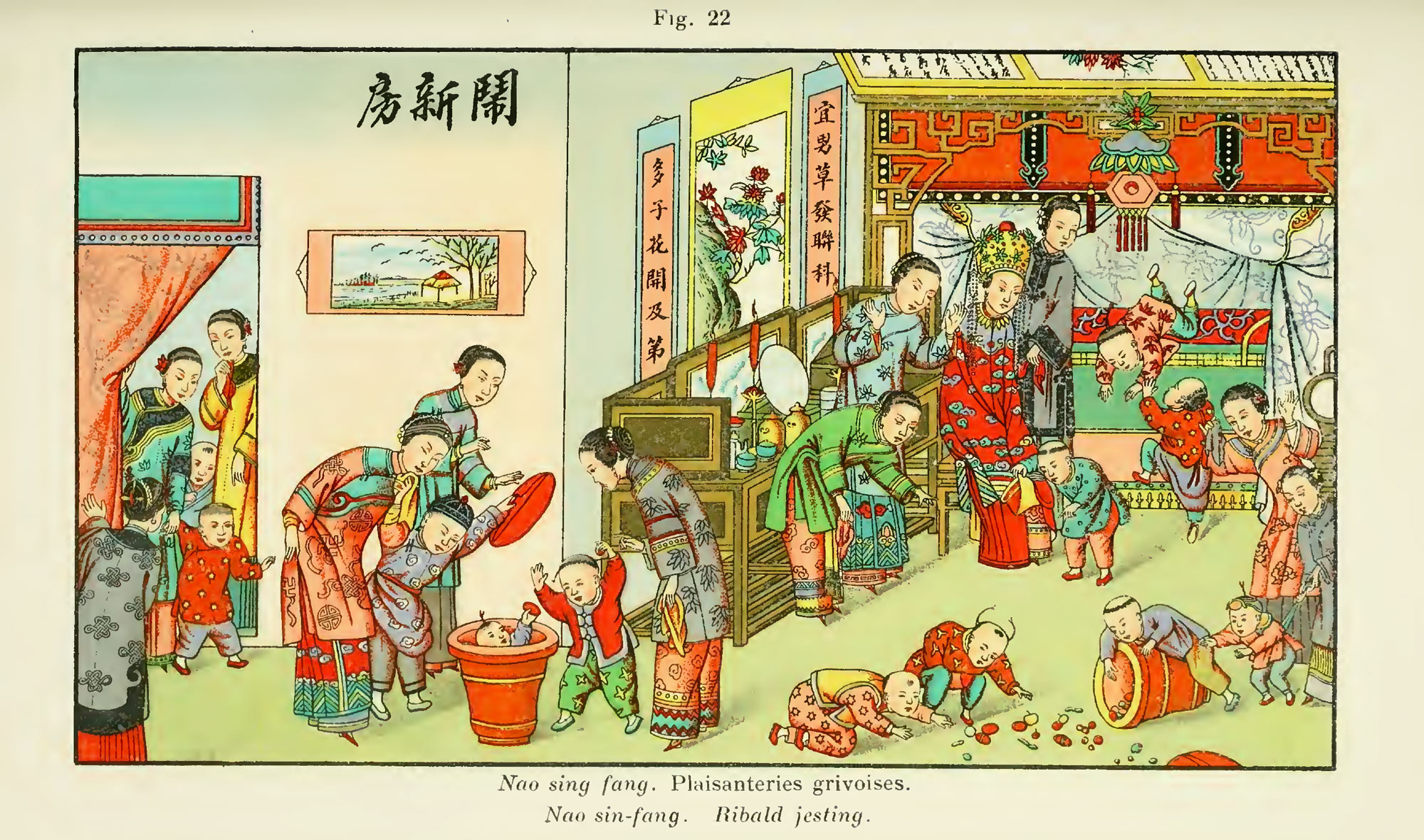

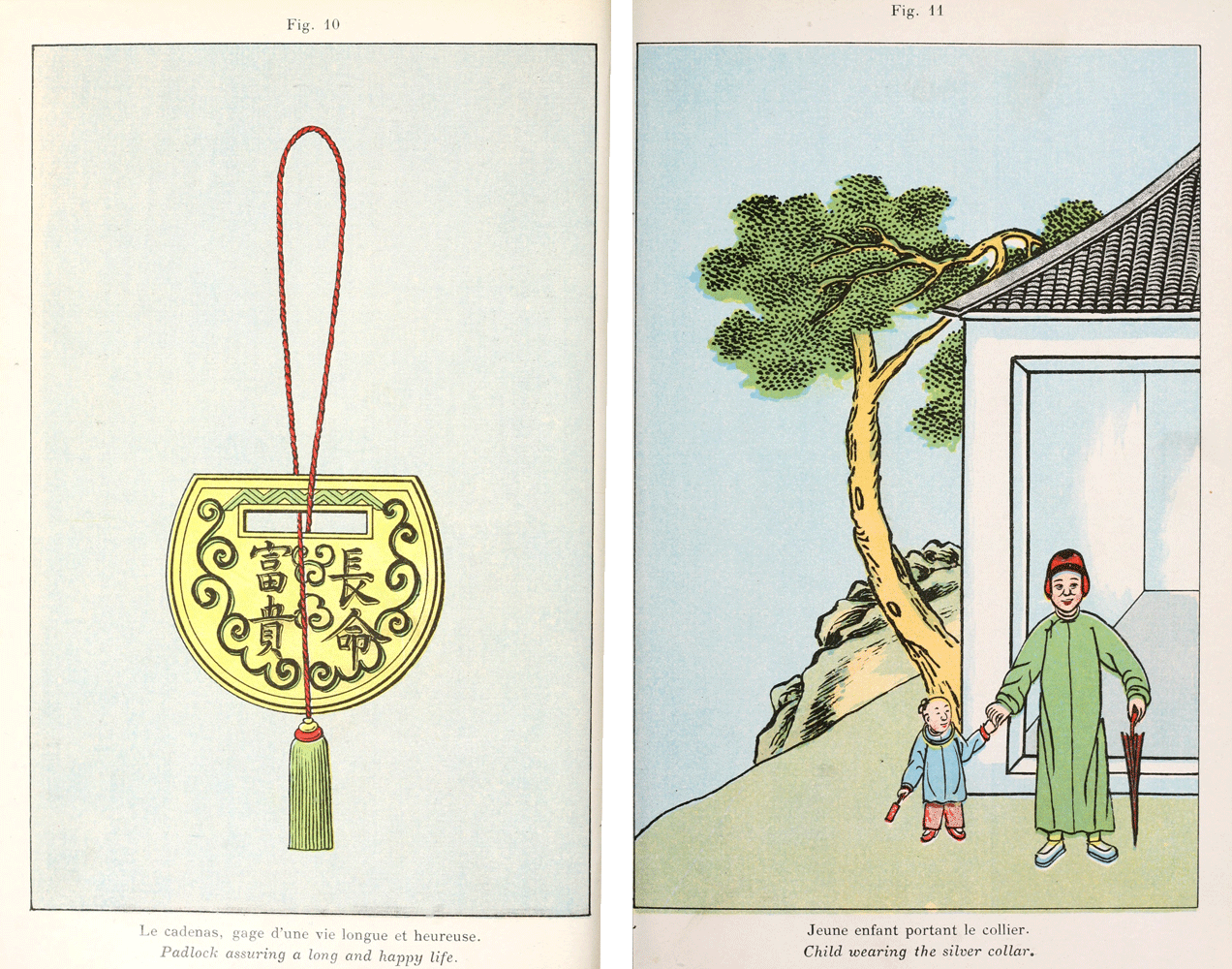

Encouraged by his friend Charles Baumert, the headmaster of the Collège de St. Ignatius in Shanghai, Doré officially began work on “Researches into Chinese Superstitions,” the first volume of which he published in 1911. While in Rugao, a county in Jiangsu province known for its long-lived residents, Doré visited ancestral halls, quizzed local scholars about traditional Chinese customs, and even followed Buddhists on their pilgrimage to the nearby mountain of Langshan. His work wasn’t limited to Rugao: Doré traveled widely across the region, including northern Jiangsu and Anhui provinces. In each place, he collected traditional folk art and studied local beliefs and rituals such as lantern-making, often writing them up for the French periodical “Relations de Chine.”

After 1918, Doré returned to Shanghai and devoted himself to completing his research. He paid close attention to the secondary literature, quoting works on Chinese folk customs by writers such as Léon Wieger and Jan Jakob Maria de Groot, but also a large number of traditional Chinese classics, including “Investiture of the Gods” and “Journey to the West.” The bibliography of the first volume alone contained 140 Chinese-language works and just 18 in foreign languages. This was no accident: In the preface to a later volume, he promised readers they would feel the characters presented in his book were “fully Chinese,” who had not been uglified or whitewashed at the hands of Europeans.

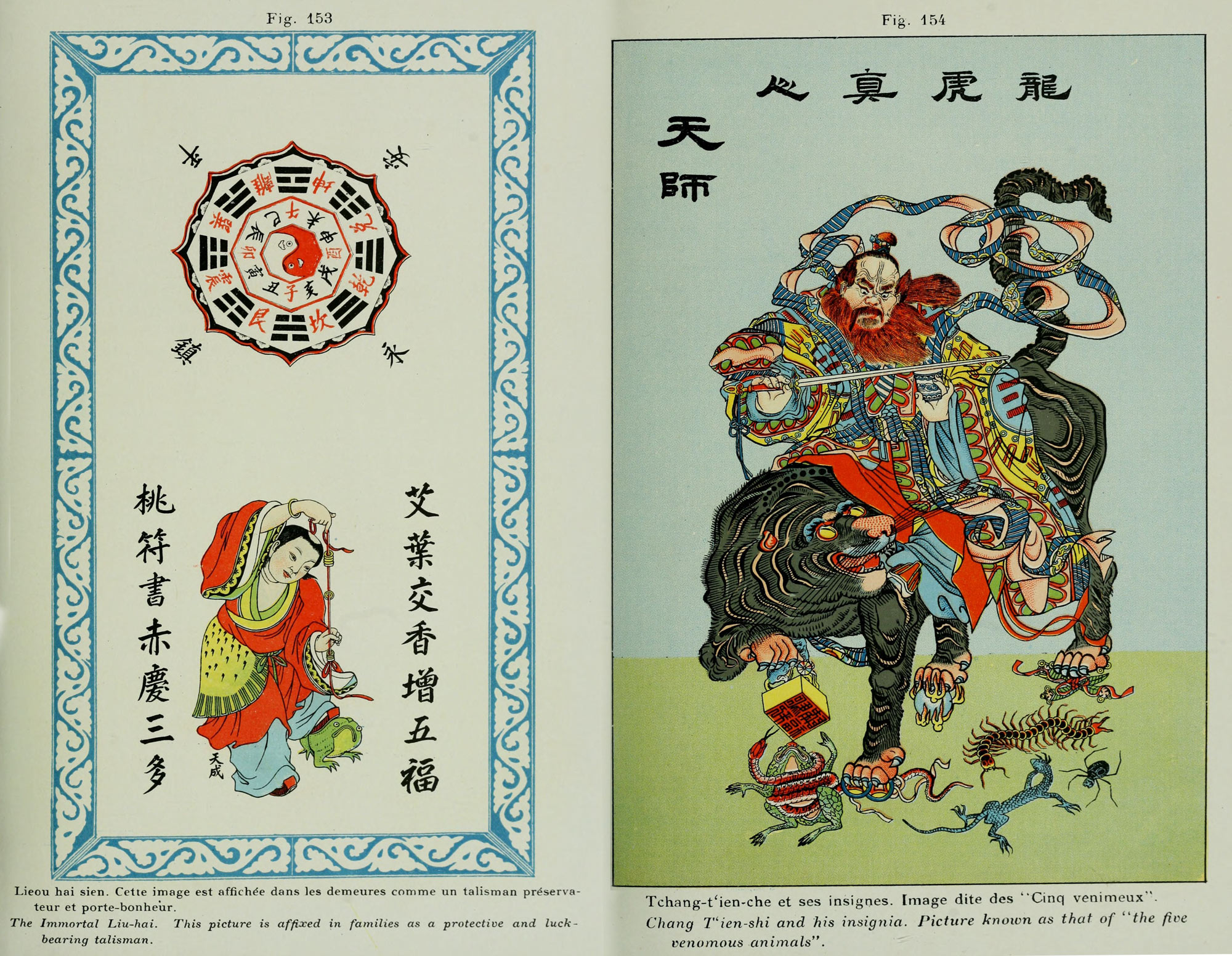

From 1911 to 1938, a total of 18 volumes of “Researches into Chinese Superstitions” were published under Doré’s name. (Doré died in Shanghai in 1931, but his order completed the series based on his notes.) Together, they contain over 820 illustrations, many of them in vibrant color. Most of these were examples of paper horses and New Year’s paintings that Doré had collected over the years, while others were new works produced by painters based at Tou-Se-We.

The series was quickly distributed to places such as Hanoi, Paris, and Leipzig, with English versions sold as far afield as Canada. In 1912, shortly after the first volume was published, Doré’s book won the Prix Stanislas Julien in France for the best work related to China.

The response to Doré’s work among Anglo-American Sinologists was less positive. Part of the issue was the series’ translation, but much of the criticism focused on the book’s supposed lack of academic rigor, including Doré’s decision to include numerous personal impressions and his use of colloquial language. Many of the critiques seem to miss the point — such as complaints that Doré rendered Buddhist terms in the local Rugao dialect. Others were simply wrong, such as the critics who accused him of using “horrible Westernized illustrations,” unaware that they had actually been created by native Chinese artists.

Nearly a century later, however, Doré seems to have gotten the last laugh. The reason is simple — many of the customs that Doré recorded have since vanished, casualties of China’s rapid modernization. His “Researches” contain some of the best — and in many cases, only — descriptions of Chinese folk belief at the turn of the 20th century. The huge number of New Year’s paintings and paper horses he bought from various places in East China, most of which are now in the collection of the Shanghai Library, are today highly valued by scholars of Chinese folk practices. According to the late research librarian Zhang Wei, Doré’s personal trove of New Year’s paintings at one point accounted for one-fifth of the library’s collection.

Translator: David Ball; editor: Wu Haiyun; visuals: Ding Yining.

(Header image: A new year’s painting shows the God of Longevity, from “Researches into Chinese Superstitions.” Collected by the University of Toronto Library)